Climate of Change

This film, narrated by Tilda Swinton, documents environmental projects and actions by ordinary people around the world.

communications

This film, narrated by Tilda Swinton, documents environmental projects and actions by ordinary people around the world.

A chapter of the virtual exhibition “Beyond Doom and Gloom: An Exploration through Letters,” this letter shows apprecation to the hopeful spirit of Rachel Carson. The exhibition is curated by environmental educator Elin Kelsey.

A chapter of the virtual exhibition “Beyond Doom and Gloom: An Exploration through Letters,” this letter discusses an alternative understanding of the crisis of Western societies. The exhibition is curated by environmental educator Elin Kelsey.

How to post your letter

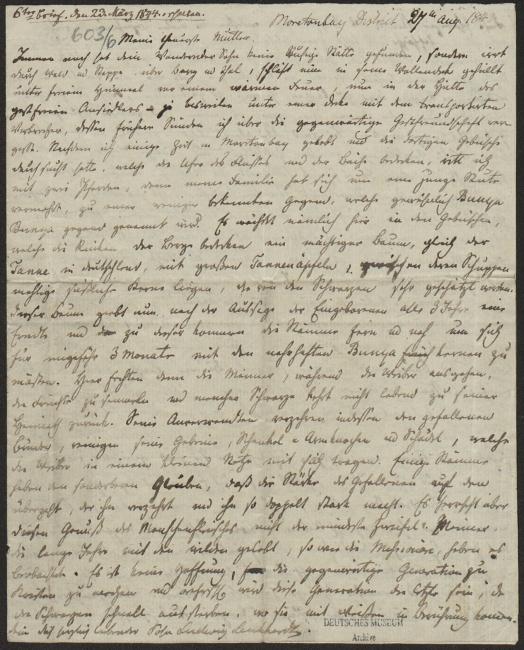

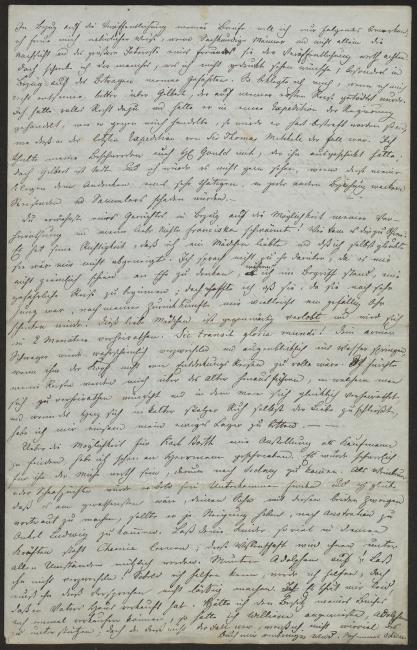

Moreton Bay District, 27 August 1843

My dearest mother,

Your wandering son has still not yet found a place for settling down, but roams across forests and plains, mountains and valleys, sleeping next to a warm fire beneath the clear sky wrapped in his woolen blanket one day, in the hut of a hospitable settler the next—indeed occasionally sharing the blanket of a transported convict, whose present hospitality makes me forget his past sins. After I had lived in Moreton Bay for a while and investigated the vegetation that covers the shores of the rivers and streams there, I took two horses—my family has by now been enlarged by a young mare—to a lesser-known region, customarily known as the Bunya Bunya district. You see, there’s a huge tree [with this name] that grows among the bushes that cover the ridges of the mountains; it is much like the fir tree of Germany and has large cones which contain harbor floury, sweet kernels between their scales and are highly valued by the blacks. According to the natives, this tree yields a harvest every 3 years and on this occasion clans arrive from near and far to gorge themselves on the nourishing Bunya kernels for approximately 3 months. At that time the men fight it out here, while the women go out to gather the fruits, and many a black man does not return to his home alive. His relatives, meanwhile, consume their slain brother, clean his bones—his thighs, arms, and skull—which the women then carry with them in small nets. Some tribes hold the curious belief that the power of the slain man passes on to whomever eats him and renders the latter twice as powerful. There is not a trace of doubt that this consumption of human flesh occurs; men, such as the missionaries who have spent long years living among the savages, have witnessed it. There is no hope of converting the present generation to Christianity and this generation will most likely be the last one, since the blacks are rapidly dying out wherever they come into contact with whites.

Then again, these black children of the bush are rather interesting creatures in many respects. They are certainly not lacking in intelligence. They seized the slightest advantages offered them by nature, and in terms of subsistence practices their discoveries are as abundant as our own, having learned to turn wheat and rye into bread, raise vegetables, catch fish, shoot game, rob bees of their honey, and use certain plants as medicinal remedies. — At the same time, they are superstitious, believe in ghosts, have dark conceptions about certain deities and some of these conceptions are rather peculiar. Indeed, it appears that their nightly dances, during which they paint stripes of white clay on themselves, are often performed for purposes of worshipping their deities or appeasing their anger. — They treat their women akin to slaves and pack animals and the poor creatures have to search out roots for their indolent men, have to carry the children, and the nets in which they transport their belongings. Every clan controls a certain district. They roam it continually to find sufficient food. At times the whole clan is gathered together, at other times they are scattered into groups of 2, 3, or 4. They construct their huts, or humpies, as they are called here, out of sticks and tree bark, since the barks of many trees can be stripped easily. Along the coast the men are commonly larger, here they are smaller, yet stocky and well-nourished. Almost every clan has its own language; frequently even among families there are a lot of varying words; yet even unacquainted clans manage to communicate with one another easily. — In general, these people are treacherous and one has to be cautious around them, even if they claim to be friendly. In Wide Bay they murdered 5 shepherds just before my arrival and here on Mr. Archer’s station they attempted to skewer a shepherd with their spears, yet fortunately he only sustained a superficial shoulder wound. — It is natural that the whites then seek revenge and that many a black loses his life. An inadequate police force seems to be the main problem. It is very difficult to convey an accurate picture of this disparity to you. To me, the

government appears to act erroneously in so many instances that it would be hard to determine what the primary mistake actually is. For the most part the whites employed at the various stations are transported convicts, almost without exception or with few exceptions unmarried, devoid of any moral principles or feelings. These men often engage in relations with the black women, who naturally stick close to the huts where they find good, ample food whereas they quite often suffer hunger in the bush. The black men, although not that strict with their women if only they receive tobacco and food, do not wish to lose their women completely and so their mood begins to sour, they utter threats, and finally seek revenge. They do this by either killing cattle or sheep, or by attacking white men outright whenever they can get them in their control. You may ask why the owners of the herds of cattle and sheep employ the services of such bad, amoral persons? The answer is: on the one hand the free settlers do not have enough experience to make themselves useful, on the other hand they lack the courage to migrate hundreds of miles inland, either alone or with wife and child, to make a living as a shepherd or cowherd there. Transported convicts, who are called “old hands” here, were forced to do so, lived in the same place for long periods of time, and thereby acquired a lot of experience. It is incredible what all such a man knows how to do. He is shepherd, cowboy, builder, sawyer, woodcutter, carpenter, blacksmith; he is knowledgeable about illnesses afflicting horses and sheep, knows how to bake bread, how to cook, how to sew —in short, all matters that life in the bush requires. At the same time he possesses extraordinary stamina, can march long distances and ride for hundreds of miles at a time. — In this regard life in the bush is highly educational; a man comes to appreciate his own strength and I have gathered a lot of experience in

this respect, since I am at present quite a decent bushman.

Since my means for travel are gradually diminishing, I will soon have to seriously consider steady employment, because I do not want to leave Australia before I have traveled all across it. I received several proposals, though I have not yet come to a decision. I have seen almost the entire northern part of the colony and hope to visit the southern part next year. From Moreton Bay I will soon return to New England, the Hunter and Sydney, where I hope to arrive within 3 months; my headway is all but painstaking because my travels progress so slowly, and because I have so much to see and to seek. I saw German missionaries at Moreton Bay, some of whom come from Berlin and Pomerania. I almost believed myself at home again when I partook in their German worship service. There are 7 families, 2 ministers, and by now the whole congregation calls 22 small children their own, who are possibly better behaved than any other children in the colony. They were supported by the government in the past; at present they make a living by gardening until their further fate has been decided. They were useful insofar as they treated the blacks with humanity and kindness and thus rendered them friendly toward the settlers. Yet as concerns education and Christianity they were unfortunately unable to accomplish much. Catholic missionaries arrived here a few months ago. I do not know whether the formal worship service of the Catholics will be better suited to keep the blacks in one place and to direct their attention to matters of the mind and of God, away from mere physical needs. There would be some hope if, as a matter of routine, the children would be taken away from their clan and educated far away. Yet the English government regards this as an infringement on the rights of British subjects, which it considers the savages to be—and thusly this hope for future success is dwindling as well. —

I hope that you have received my letters; I only have one of yours and I am asking you to write to me by way of William. Farewell, all of you, and please keep me in your hearts and minds, especially you, my dear mother,

Most affectionately, your loving son,

Ludwig Leichhardt

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/6.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.

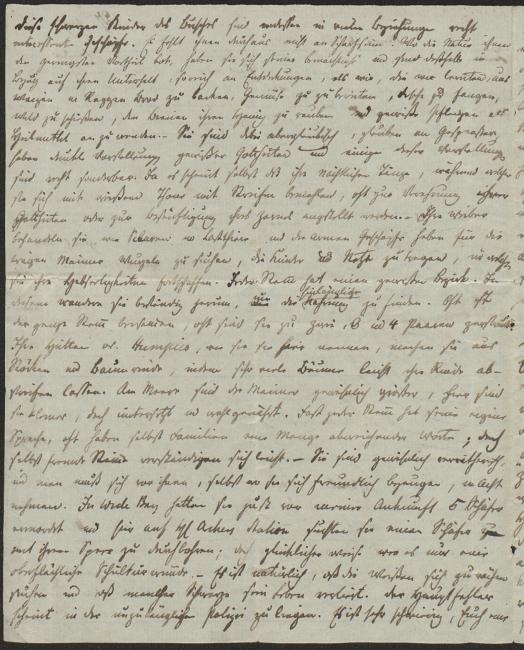

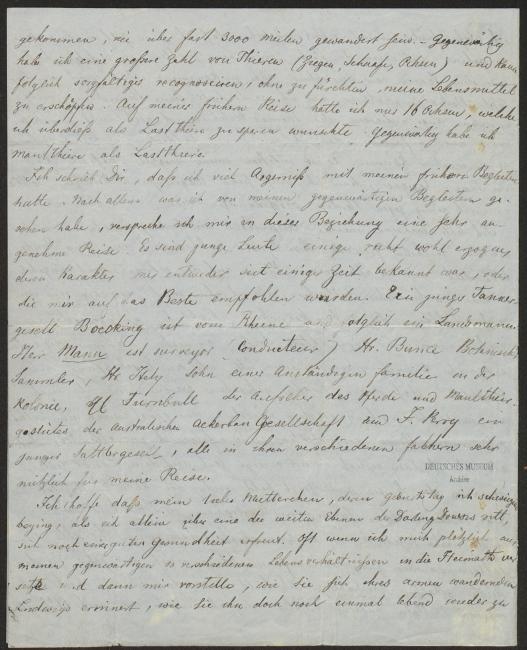

Darling Downs, 22 February 1848

My dearest brother-in-law,

Four months have passed since I informed you about my return from Peak Range. I have used this time to make preparations for a new expedition, and in a few days will be once more ready to penetrate Australia’s interior, and, if God grants me the strength, to cross the entire continent. I have made an effort to find good, valiant men and believe that Classen will be well-suited to my endeavor, although a land expedition differs significantly from even the most trying of sea voyages. Another friend, Mr. Hentig, has also joined me. I have hired two workmen and will take two blacks along, one of whom accompanied me on my last journey. The entire company is thus comprised of 7 men and I hope that this number will prove entirely sufficient. At present I am in possession of 20 mules, 7 horses, and 50 bullocks, 20 of which were a gift from Mr. Robinson and 30 of which were gifted to me by the government. I told you that a Mr. Kennedy had been sent by the government to follow the Victoria River to its mouth, which Sir Thomas Mitchell had seen but not completely explored on his expedition. Mr. Kennedy has returned and has determined that the river turns southward and loses itself in Sturt’s desert, and that it is probably identical with “Coopers Creek,” which Captain Sturt mentions in his expedition [account]. I am therefore once again alone in the field and think that I can solve a great number of interesting questions if I only succeed in bypassing the northern tip of the desert.

I left Sydney in December, after I had made all my purchases. A trip to the Hunter River, where I went to visit several friends, delayed me by about a week. I then traveled to Captain King in Port Stephens in order to repeat a few earlier observations using my thermometer to determine the elevation above sea level; after that I bought 6 fresh mules and traveled through New England, where I picked up 20 bullocks, to my present location, the hospitable abode of Mr. Fr. Bracker, a master sheep farmer from Mecklenburg. I had scarcely gotten under shelter when the heavy rains commenced that are characteristic in this part of the colony from the end of January and through February. The colony had been suffering immensely from drought, and the sudden cold showers,

which rained down on New England’s freshly shorn flocks of sheep, standing utterly exposed to the night air, caused more damage than even the drought had. 100,000 sheep are said to have perished across the colony while the rains lasted. I myself witnessed the death of 800 in one night, when an entire flock of 1000 head sought shelter in stables and houses and feared neither the threats of people nor the dogs. As soon as the rain ended, and during the rains as well, all of nature, which had appeared almost dead to our eyes, tired of the monotonous yellow of withered vegetation, came to life, and the loveliest, sunny green enveloped the open forests and treeless pasture lands. This switch from an almost complete cessation of plant growth, from a desolate paralysis of nature, to the most luscious vegetation and an omnipresent, teeming world of insects reminds the eyewitness of Humboldt’s description of savannahs at the beginning of the rainy season.

As soon as the heaviest rains had passed and streams and rivers had become passable again I began to consolidate all of my possessions, which had been scattered almost across the entire Darling Downs, at Mr. Bracker’s in Rosenthal. I also had to look for such people as I wanted to take along with me. This is how I have spent my time for the last four weeks—almost constantly in the saddle and frequently dead tired. My provisions are likely to arrive here tomorrow or the day after, and this would allow me to set out next Monday, 28 February. I have had the pleasure to learn that the geographical society in London has awarded me one of their medals and that the geographical society in Paris has bestowed a similar honor upon me. I am of course delighted that such astute men deem me worthy of such an honor, yet I have never striven for honor but rather worked on behalf of science and science alone, and will continue to do so even if not one person in the world were to pay any attention to me. I am afraid to lose God’s blessing should I let my vanity take over and should the sincere, calm, painstaking quest for scientific knowledge become mixed up with ambitious striving for fame and recognition.

Mr. Durando of Paris writes that he has successfully received the scanty remains of my botanical collection and that Mr. Decaisne is

busy examining it. Even if my dried plants should not be suitable for determining new species, they should nevertheless prove interesting and useful for the botanical geography of New Holland. I have been very unfortunate with regard to my seeds, since none of the local institutions are suitable for growing and raising tropical plants. You might perhaps wonder why I did not send these collections to one of our German museums? The answer is that I conducted my studies of natural history primarily in English and French museums, and that I did not cultivate friendly relations with any of my compatriots during my youth, which would have obliged me to consider my friends first. Durando was a botanist and a very dear friend of mine. His circumstances were dire; I wanted to provide him with an opportunity to distinguish himself should my collection actually be of some value. This friendly tie to Durando compelled me to send the collection to him instead of sending it to a famous English or German botanist. Durando, however, has neither time nor confidence enough to undertake this project and has therefore given the collection to Mr. Descaisne [sic], who was always quite cordial and accommodating in his behavior toward me.

It was also quite a happy coincidence that I got to see my journal and my maps before departing. The maps are very nice and I am deeply indebted to Mr. Arrowsmith for transforming my rough sketches so beautifully. I will let others pass judgment on my book; it is a simple tale about our expedition and an equally simple description of the areas and things that I saw. If only the traveler is truthful, the scholar at home will thank him. He can never render a minor natural environment impressive and cannot describe the moderate mountain ranges of Australia as though they were the monumental ranges of America. I did not write intending to evoke maximum effect, and hardly thought it worth my while to employ the glowing language of a poetic huntsman to describe hunting kangaroos or emus. The public appears favorably inclined toward the book. At least it has been favorably reviewed in the papers. I would very much like to correct several very unfortunate typographical errors, and should Franciska truly intend to translate it, she would do well to contact Mr. Boone in London, to whom I intend to send

a list of these errors. —

The governor of the colony, Sir Charles FitzRoy, has always been favorably inclined toward my endeavor, and made me a present of 30 bullocks without me even requesting them. The unhappy man lost his wife through a most heartbreaking accident. He loves to take the reins of his horses when going out for a drive and it is said that he is very skilled. The family lived in Paramatta, about 3 German miles from Sydney, and the governor used to come to Sydney once a week, which he usually did in a small coach drawn by 4 horses, accompanied by his son and one servant. About 3 months ago, shortly after I had left Sydney, he drove to a wedding, along with his wife and secretary. The horses bolted on him, the coach tipped over, and Lady Mary and the secretary (Lieutenant Masters) sustained such severe injuries that both died the very same day. Lady Mary was very popular and the entire colony was in mourning. He blames himself for causing this tragedy and at present lives a very secluded life.

Although I most certainly feel strong enough to embark on this new, long expedition, I cannot, however, deny that my constitution has been seriously weakened, particularly on my latest expedition, and that I now have much less muscle strength than I did 4 years ago, when I embarked on my first long journey. In particular, I am suffering from heart palpitations, which frequently cause me quite a bit of worry.

I hope that my letter finds you all in the best of health and that my dear, beloved mother will stay with us for quite a long time yet. For if I return from my expedition alive and in good health, I intend to come to Europe for two years and to pay all of you a very long visit.

Faith thou needest, and must dare

Or the gods withhold their hand

Nought but miracle can bear

Man into the wonderland (I should say rather mother land!)

I wish I could take one of my two blacks home with me. He is a most useful and yet docile lad and not at all as wild as the black who came along on my first expedition. He is called Jimmy or Wommai or Kilalli. The other one is less useful. Yet both possess extremely sharp eyesight, which makes them of excellent use to me.

Claßen will probably write to Herrmann. I have so much yet to write that I will scarcely find time to do so myself. Farewell, my dearest brother-in-law and my sister, convey my greetings to dear mother and our entire family,

Most affectionately, your loving brother-in-law and brother

Ludwig Leichhardt

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/16.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.

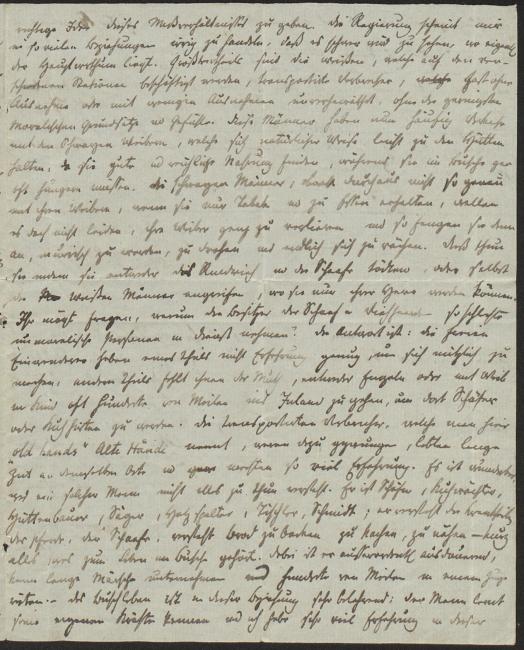

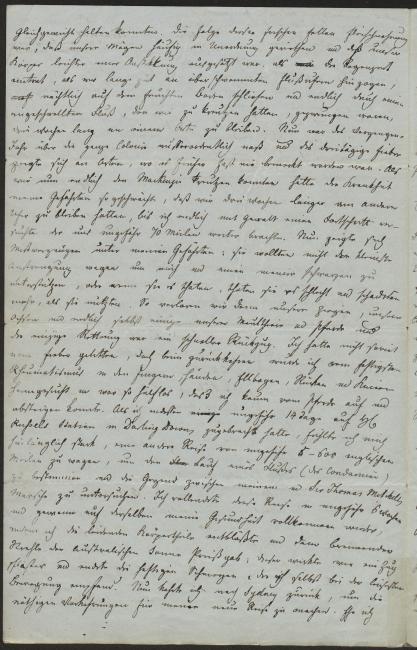

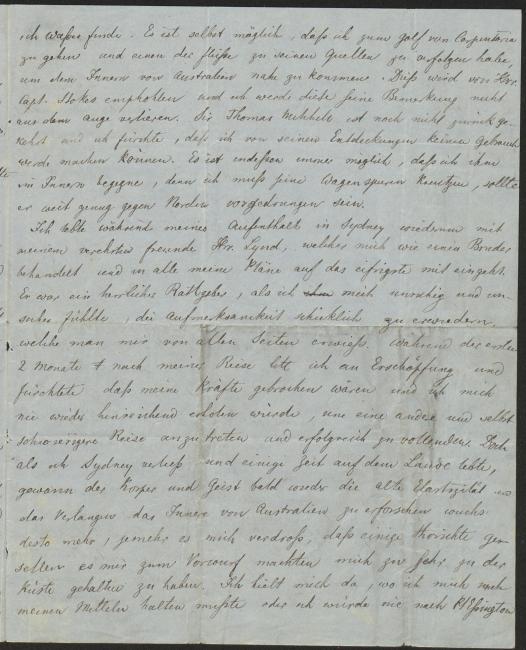

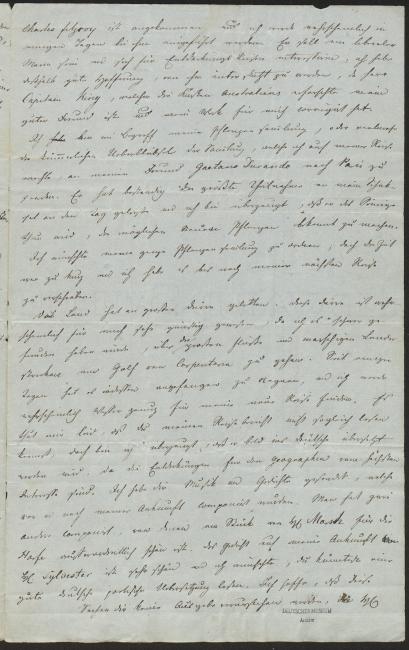

Sydney, 21 October 1847

I had scarcely finished my letter when Mr. Holt arrived and called a boy carrying an enormous portfolio into my room. He said: “I received this portfolio from a business partner in Cottbus, whose address will tell you the rest.” I read the address and recognized your dear name. I opened it at once, searched for a letter among the newspapers and religious literature, and rejoiced at seeing your letter and the picture of dear mother. Unfortunately the glass of the picture frame had shattered and damaged the picture itself a little. Everyone who beheld it said they had never seen a better daguerreotype, and Mr. Lynd opined I only had to don a bonnet and shave my beard and I would resemble it completely. I thank you, my dear brother-in-law. You have given me great, great pleasure! You will by now also have learned from my letters that the picture of my blessed father arrived here in one piece, was framed, and is hanging beside the one of my friend Nicholson. What can I tell you with regards to your gracious efforts to secure the king’s clemency on my behalf? It is a comforting feeling to be at peace with my native country, to be able return to it without impediments, to be able to see my family again, even if fate had decided that my wishes in this regard will never come true. This possibility is what a free man values so dearly. I am completely satisfied with the cabinet’s decree; I even willingly accede to the stipulation; it was necessary for the king to uphold the appearance of consistency. What the government deemed necessary to deny the unknown petitioner it now does not want to grant the newly famous man; because if the request had been right, [the government] would not have denied him it originally. I was not displeased with the institution of universal military service; I was displeased that the government did not think it had the power to grant exceptions in special cases. When William left Berlin the question arose whether I was to best serve my country and to serve science by receiving a thorough education in Europe’s biggest museums and by traveling to faraway corners of the globe, or whether I should spend a year learning how to exercise on the Köpenick parade grounds. The government decided on the latter, I on the former. I was in the wrong, because I followed my calling and violated the law—a law that is a dead, unchangeable power—not law moderated by a free-thinking ruler. But enough about that! I have often enough worked myself into a rage speaking on this topic and believe me when I tell you that the English were more inclined toward fanning the flame than extinguishing it. As the thought of

once again belonging to my native country calms my mind, an unbidden feeling of pride arises about the fact that I owe my happiness to the example of men whose deeds appeared like fairy tales to the boy, filled the youth with enthusiasm, and finally called on him to pursue a similar path. How often did the soaring adventures of Prince Pückler sweep me away and fill my breast with longing for blue faraway lands, which he sought out free and unhampered, quickly grasping and truthfully and pleasantly rendering all of the highlights and important characteristics of the lands and peoples he encountered. And Humboldt? His example will always serve as my guiding principle. I strive to be like him, but I feel that my means are still too limited to truly emulate him. By him I mean the wanderer through America, not the great, serene researcher who is now so admirably managing the success of his youth. — The difficulties I have on my expeditions are due to the amount of time that I spend away from the inhabited part of the colony, away from any possible support. I am forced to limit the number of my companions, as well as my provisions, as much as possible. I myself have to do physical labor and usually the hard work falls to me. In a tropical climate, our way of doing things causes our limbs, especially our feet, to grow very tired, and when the day’s work has been accomplished and we have made camp it requires a great deal of energy to overcome this tiredness and to make scientific observations. Whenever we stray from the vicinity of the rivers, I am forced to ride 30–50 miles ahead to find water, while the rest of the group, with the exception of one black man, who I take along, remains at camp. Then it is also extremely difficult to ensure order and obedience among my companions. Open defiance causes little harm, since my cause and my motives are just, and I am soon able to convince them, or at least the others, of their folly. Yet if they act secretly and insidiously, they are able to poison the entire camp and to frustrate all of my plans. I believe this to have been the case during my last, failed endeavor. A single “Sauve qui peut” is able to cause even those with a strong determination to falter.

I read your news about our family and about the vital happenings in state and church with the greatest interest. Much is expected of the Prussian constitution. Everyone is curious to see how freedom will develop among a people that is generally acknowledged to be the best-educated one. How will its ideas of liberty manifest themselves and how will its heads-of-state respond to the exuberance of this youthful freedom?

The Prussian is well-educated, but not in political matters; he still has much hard learning before him. Worthy representatives of the people’s interests, calm discussions, clear, powerful public speeches, a government willing to listen to the people’s representatives without prejudice, and preparedness to act according to the emergent will of the people rather than pursuing the interests of the few—these are all fruits of a plant that matures only slowly. —

I would willingly sign the profession of faith proposed by the German Catholics . The simple “I believe in Jesus Christ our Savior” utterly suffices; but I do not yet understand the value of believing in a universal Catholic Church! Is it that one sole universal church will be recognized across the entire globe? This would be desirable. Many of the sermons are extremely powerful and are a credit to both the German language and to the men who deliver them.

Yet why did you not tell me anything about the state of German poetry? Have all the German poets gone to sleep? Does the present time not lend itself to poetic expression? We were brought up on the idea that great times bring forth great poets and I cannot help but think that we live during great times. After three years of living in the wilderness I have re-read Schiller’s poems. What a magnificent, noble language! What noble feelings lived in the breast of this marvelous man! Music has never left as deep an impression on me as it did during my sea voyage from England to Sydney. It was a fierce night and the sea was quietly roaring beneath the keel of the steadily advancing ship. I had been listening to the muddled din for a long time when I suddenly got up and went to the cabin of my travel companion, Mr. Marsh, who was a great master harpist and who was improvising on this instrument when I entered. The orderly sounds, after the chaotic, dark roar of the wind and the waves, were so intense and pleasurable that they brought tears to my eyes. A similar feeling overcame me when I read Schiller again. How exceedingly true are the words of this visionary even though he himself never experienced this situation:

And as, after heartbreaking pain

And separation’s bitter smart

The child repentant seeks again

Upon his mother’s breast relief:

So to the thoughts of early days

When innocence was yet unstained

From foreign lands and foreign ways

Song brings the wanderer home, regained —

As regards the publication of my letters I only wish to tell you the following: I am of course pleased that educated men, not just the consideration and greater interest of a friend, deem them worthy of publication. Yet there are things I write to which I would not wish to see appear in print, especially as concerns the behavior of my travel companions. If I remember correctly, I complained bitterly about Gilbert, who was killed in my first expedition. I was completely justified in so doing, and if he had behaved as he did toward me as part of an official government-sponsored expedition, then he would have incurred severe punishment, as the example of Sir Thomas Mitchell’s latest expedition shows. I also shared my complaints with Mr. Gould, who had sent him; but Gilbert is dead and it would not please me if my complaints were to harm the memory of a very energetic traveler and collector who behaved valiantly in all other respects. —

You mentioned some nonsense about the possibly of me getting married, and that my dear niece Franciska is very excited about it! How did you hear of this? It is true that I loved a girl and that I even believed that she was not disinclined toward me. I did not talk to her about this matter, since I deemed it unsuitable to think of marriage when I was about to embark on a dangerous journey; yet I hoped that she, since she was still very young, would perhaps be willing to receive me after my return. This lovely girl is presently engaged and will be married in 2 months. Sic transit gloria mundi! Your poor brother-in-law would most likely despair and drown himself at once if thoughts of expeditions would not so completely fill his mind. I am afraid that my travels will take me beyond the age at which one wishes to marry and at which happy marriages are forged, and if my heart, in cold, proud composure closes itself off to love, then I shall have to face eternity alone. — —

written to Hermann about the possibility of finding a position in business for Karl Barth here. It would hardly be worth the trouble for him to come to Sydney for this. As a vintner or sheep farmer he would soon enough find a place and I believe that it would be most advisable to familiarize your son with these two branches should he ever feel the inclination to come live with his Uncle Ludwig in Australia. If it is at all in your power, make your children study chemistry; this science will prove useful to them under any circumstance. Cheer up Adolph! Don’t let him despair! As soon as I can be of assistance, I will help out, yet this promise does not mean that he can take it easy. I am sorry to hear that he has sold father’s house. Had I been able to sell the rights to my book for a lump sum, then I would have instructed William to assist Adolph; yet because this was not the case I do not know how much I income I will derive from the book.

Once again, adieu.

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/15.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.

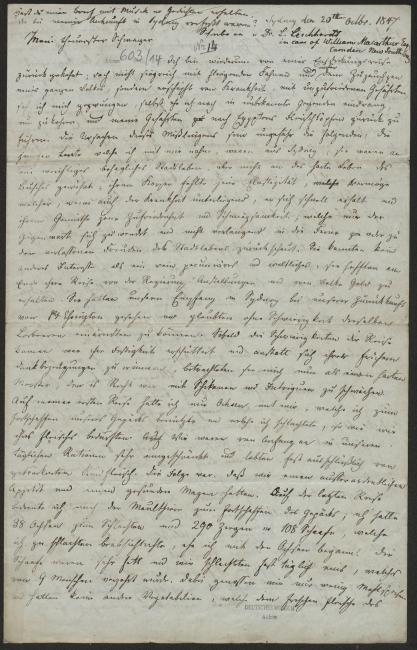

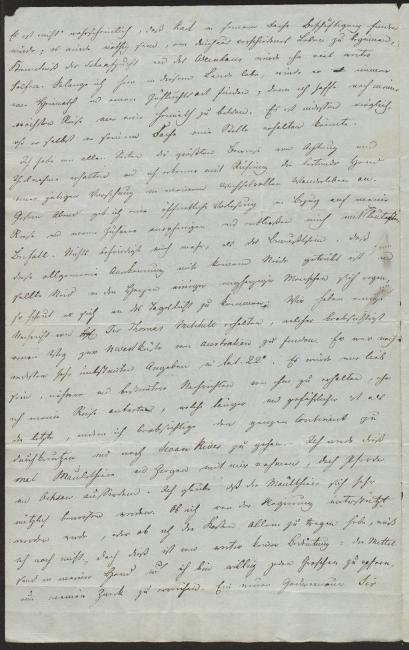

Camden/Sydney, 20 October 1847

At the house of William Macarthur

My dearest brother-in-law,

I have once more returned from my expedition, yet not victorious with flying banners, bathing in the jubilations of the people, but on account of exhaustion from disease and due to malcontent companions I was forced to return and to lead my companions back to the fleshpots of Egypt before I ever even had the chance to penetrate unknown areas. The reasons for this failure are more or less as follows: the young men that I had taken along with me were from Sydney; they were used to a soft, comfortable city existence but not the hard life in the bush; their bodies lacked the elasticity that allows someone to recover quickly even after having fallen ill, and their minds lacked the contentedness and flexibility that allows one to focus entirely on the present instead looking longingly into the future or back to the lost pleasures of city life. They were interested in nothing but purely pecuniary and mundane considerations: they hoped to receive government posts and obtain money from the people after completing the expedition. They had witnessed the welcome that we had received upon our return from Port Essington and thought they would be able to win similar laurels without difficulty. As soon as the hardships of the journey became apparent, their conviction was shaken, and instead of remembering their former words of gratitude they came to see me as a harsh master who they had a right to weaken by way of harassment and intrigues.

On my first expedition I brought along only bullocks, which I used for carrying our baggage and which I slaughtered whenever we were in need of meat. From the start we had to make do with very limited daily rations and subsisted almost exclusively on dried beef. We consequently developed a big appetite and our stomachs remained healthy. On my latest expedition I used mules for carrying our packs; for purposes of slaughtering I brought along 38 bullocks as well as 290 goats and 108 sheep, which I intended to slaughter ahead of the bullocks. The sheep were very fat and we slaughtered one almost every day, which was shared among 9 men. Moreover, we ate few flour-based dishes and had no vegetables that could have balanced out the fresh meat.

As a consequence of this diet of fresh, fat meat, our stomachs were frequently upset and our bodies more prone to infection. When the rainy season started, we traveled alongside flooded river banks for long stretches of time, slept on damp grounds every night, and a swollen river that we needed to cross finally forced us to remain in one spot for three weeks. Over the past year the entire colony has been abnormally wet and tertian fever occurred in places where it had hardly ever been known before. When we were finally able to cross the Mackenzie this disease had weakened my companions to such an extent that we had to rest on the opposite bank for another three weeks, until I finally tried to push onwards forcibly, which resulted in us covering a further distance of about 70 miles. My companions now became disgruntled; they were unwilling to exert even the smallest effort to assist me and one of my blacks, or, if they did anything at all, they did it badly and did more damage than good. Thus we lost our goats, our bullocks, and in the end even some of our mules and horses, and a hasty retreat was our only salvation. The fever had not caused me much suffering, yet on the return journey I was seized by rheumatism in my fingers, hands, elbow, back, and knees, and was so helpless that I was scarcely able to mount and dismount my horse. However, after I had spent about 14 days resting at Mr. Russel’s station in the Darling Downs, I felt strong enough to attempt a different expedition of about 5–600 miles, in order to determine the course of a river (the Condamine), and to explore the area that lay between my own path and Sir Thomas Mitchell’s. It took me about six weeks to complete this expedition and I completely recovered my health during it by exposing my ailing limbs to the burning rays of the Australian sun; these acted like a blistering plaster and alleviated the acute pains that even the slightest movement had heretofore caused me. I then returned to Sydney to make the necessary preparations for my new expedition.

Before I left the Darling Downs I was delighted to learn that 5 of my runaway mules had returned after straying off course for about 600 miles, which saved me a considerable sum of money. I will have to spend approximately £200 on new equipment; my original expenditures totaled about £650, and thus the entire outlay for both the failed and the new expedition will amount to £850. This is a lot of money in Germany and quite a hefty sum here as well, yet I live for, I exist solely through my ventures and leave the future up to God. You gave me magnificent advice in your wonderful last letter, but I cannot follow it, it is not in my nature. An endless, indomitable drive compels me to study this natural environment and to solve this country’s mysteries. It is a lovely, complex field of study and if I had good companions I would roam Australia’s forests as happy as the son of an Irish king, yet to find competent companions is so extraordinarily difficult. For the most part only materialistic, small-minded, amoral young men approach me, since they have no other way of advancement. On my first expedition they were almost all still boys, with 2 exceptions, and therefore I was able to force those who rebelled against me to obey me once more. On my next expedition Mr. Classen will accompany me, who has been to almost all shores and crossed all oceans over the past 12 years, who is quite a well-educated young man, and who has suffered enough hardship so as to be sufficiently prepared for an expedition such as mine.

Mr. Lynd, my amiable host, has received orders to leave Sydney and to proceed to New Zealand, where the aborigines are making a large military presence necessary. I therefore have to look for another home, and although I can everywhere find hospitable accommodations for myself, I do require a safe place for my ever-increasing collections, where they will not only be sheltered from insects and the elements, but also easily accessible for whenever I have time to study them.

What you told me with regard to the intercession made by the gracious Princess Pückler is quite good and pleasing. I would very gladly be at peace with my native country and not run the risk of being incarcerated upon my return.

I wish I could see all of you and dear mother one more time, but there is no hope for that as long as I have not crossed this continent, which will most likely take two to three years. — I shall hardly be able to recognize Germany. The railroad will surely have given it a different character. Where will the new discovery of averting pain by inhaling ether lead? Will it not serve to transform men into soft, pain-shy creatures unable to endure even the slightest affliction with patience and manliness? And then, if a savage warrior people should invade from Asia, the times when effete Rome succumbed to the strong primitives from the north will be upon us once again. From my perspective, a regressive element seems to have entered educational practices as well. Everything is becoming outwardly-oriented; diagrams and figures facilitate comprehension, and whereas we racked our brains by reading and studying in the past, the eye now easily grasps meaning when beholding a picture. Yet is this not taking it a step too far? Will students not fear and try to avoid serious courses of study? It is admirable to combine both avenues of learning, yet man’s inherent idleness will soon induce him to skip the harder aspect of the work.

William has probably told you that Mr. Boon, a well-respected bookseller, will publish my journal. He has promised me half of the proceeds, yet I am afraid that this half of the profits will not amount to very much. If I had had the time, I would have composed the work in German but I would have to take some time to reacquaint myself with the German language before I could once more express myself in it with confidence and ease. Had I received a lump sum for the work I would have tried to help out Adolph, since I am truly worried, after paying off the debt I owe to William. Yet at present I cannot give any concrete assurances, aside from those of my good will. I hope that our dear mother is enjoying a worry-free life and that it pleases God to keep her for a long time yet and to allow us to see each other again.

Farewell, my dearest brother-in-law, give a kiss to my dear sister and your children, convey my greetings to dear mother and my relatives and friends, and keep me in your heart

Most affectionately, your loving friend and brother-in-law

Ludwig Leichhardt

[Post scripta at head of first page:] Did you receive my letter containing the music and poems that were composed upon my arrival in Sydney? Address your letters to

Dr. L. Leichhardt

in care of William Macarthur

Camden New South Wales

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/14.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.

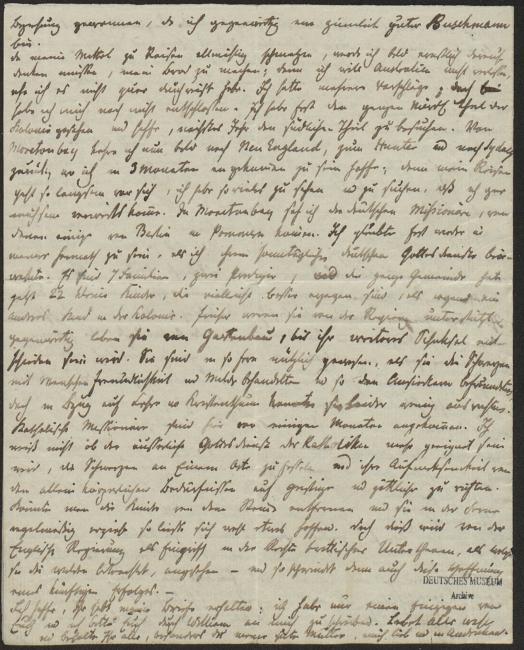

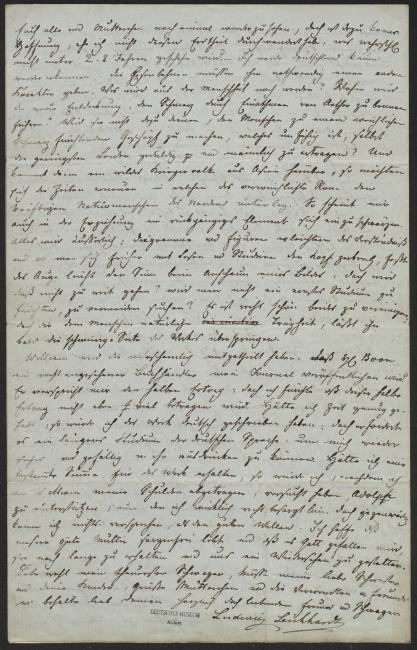

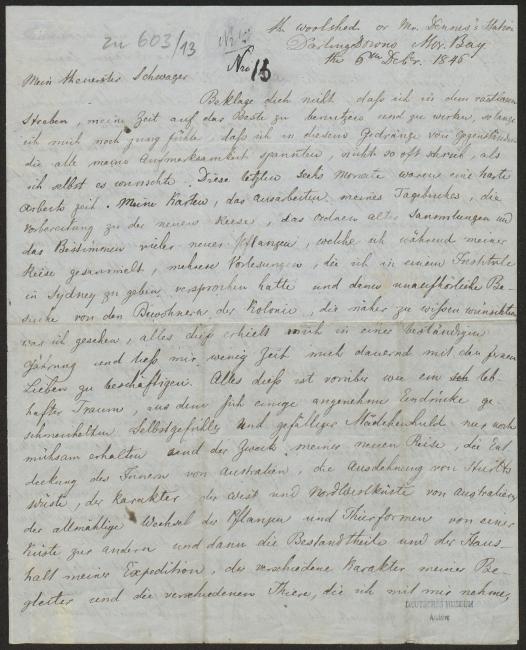

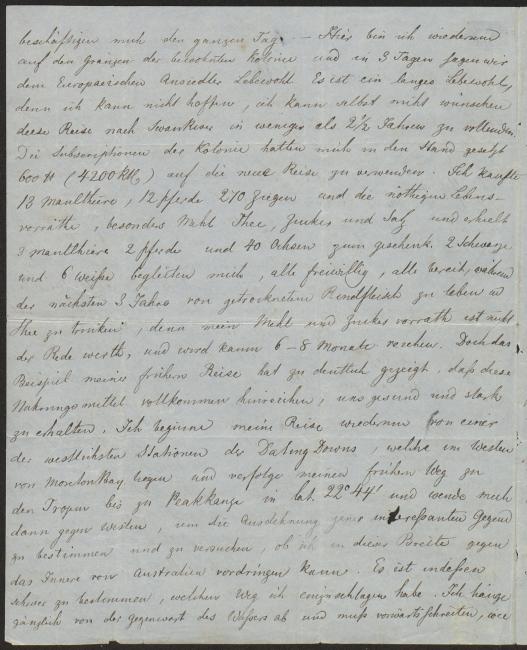

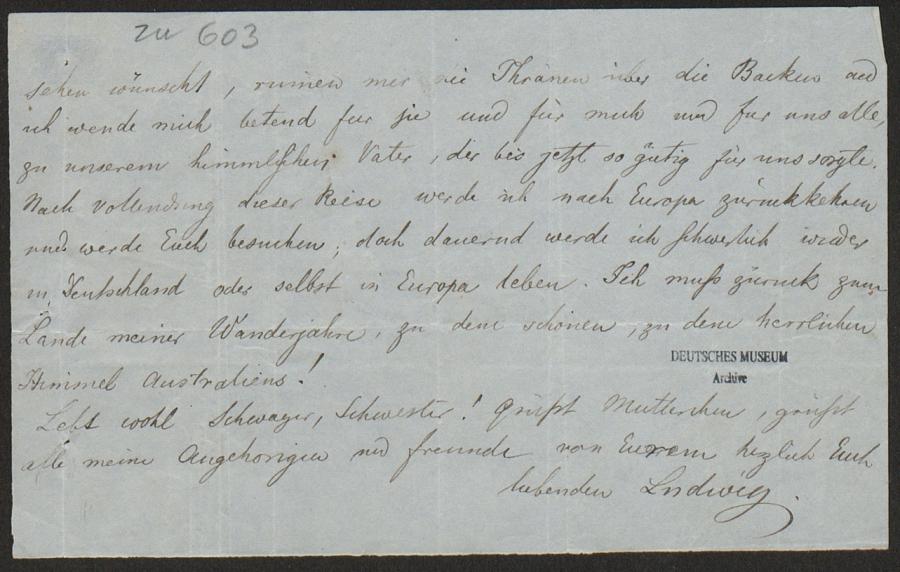

The Woolshed, or Mr. Dennis’s Station, Darling Downs, 6 December 1846

My dearest brother-in-law,

Do not complain that I do not write as often as I myself wish to, occupied as I am with my restless quest to fully utilize and make the best of my time as long as I still feel young, with the crush of subjects that demand all of my attention. These last six months were a time of hard work. My maps, writing up my journal, preparations for the new expedition, organizing old collections, classifying the many new plants that I had collected on my travels, several lectures, which I had promised to give at an institute in Sydney, and then the unceasing visits by colony residents, who wished to learn more specific details about what I had seen—all of this has kept me in a state of perpetual unrest and left me with little time to devote myself more consistently to loved ones faraway. All of this has passed like a vivid dream, of which only a few pleasant impressions of flattered pride and agreeable maidenly grace barely manage to remain, and I spend all day preoccupied with the goals of my new expedition, the exploration of Australia’s interior, the extensiveness of Sturt’s desert, the character of Australia’s west and northwest coast, the gradual changes in flora and fauna from one coast to the other, as well as the equipment and budgeting of my expedition, the various personalities of my companions and the diverse kinds of animals which I am taking with me.

Once again I find myself on the edges of the inhabited colony and in 3 days we shall bid farewell to the European settlers. It will be a long farewell because I cannot hope, I cannot even wish to complete the journey to Swan River in less than 2½ years. The colony’s subscriptions enabled me to spend £600 (4200 Rtl) on this new expedition. I bought 13 mules, 12 horses, 270 goats, and the necessary provisions, especially flour, tea, sugar, and salt, and I received 3 mules, 3 horses, and 40 bullocks as a gift. 2 blacks and 6 whites are accompanying me, all volunteers, all ready to live on dried beef and tea, since my rations of flour and sugar are not worth speaking of and will hardly last 6–8 months. Yet the example of my earlier expedition has made it abundantly clear that this food entirely suffices to keep us strong and in good health. Once more I am setting out on my journey from one of the western stations in the Darling Downs, which are situated in the west of Moreton Bay, and will follow my earlier path to the tropics as far as Peak Range at 22° 44’ latitude, and will then turn westward to determine the expansiveness of that interesting region and to attempt to penetrate Australia’s interior at this latitude. However, it is difficult to determine which path I should take. I am completely dependent on the presence of water, and have to move ahead

according to where I find it. It is even possible that I will have to travel to the Gulf of Carpentaria and from there follow a river to its source in order to approach Australia’s interior. Captain Stokes recommends this strategy and I will keep his remarks in mind. Sir Thomas Mitchell has not yet returned and I am afraid that I will not be able to make use of his discoveries. Then again, it is always a possibility that I will meet him in the interior since I will surely cross his tracks should he have advanced far enough north.

During my stay in Sydney, I once again lived with my dear friend Mr. Lynd, who treats me like a brother and takes a keen interest in all of my plans. He was a wonderful mentor when I felt anxious and uncertain about how to properly respond to the attention that I was accorded from all sides. I suffered from exhaustion for the first two months after my expedition and feared that my strength was gone and that I would never recover adequately enough to undertake and successfully complete another and even more difficult journey. Yet when I left Sydney and lived in the countryside for a while, my body and my mind soon recovered their old resilience, and the more annoyed I became that a few foolish fellows criticized me for having stayed too close to the coast, the more my desire to explore the interior of Australia grew again. I stayed where I had to stay on account of my supplies or I would have never reached Port Essington,

would have never been able to journey across almost 3000 miles. — This time I have a larger number of animals (goats, sheep, bullocks) and can therefore more thoroughly reconnoiter without fear of exhausting my supplies. During my earlier expedition I only had 16 bullocks, which moreover, I sought to spare as pack animals. This time I have mules for pack animals.

I wrote to you that I had a lot of trouble with my earlier companions. After all that I have seen of my present companions, I have high hopes for a very pleasant journey in this regard. These are young people, some of them very well-educated, whose character I have either known for some time, or who came highly recommended. A young tanner’s apprentice, Boecking, is from the Rhine region and hence a compatriot. Mr. Mann is a surveyor, Mr. Bunce a botanical collector, Mr. Hely the son of one of the colony’s upstanding families, Mr. Turnbull the overseer of the Australian Agricultural Society’s horse and mule stud, and J. Perry a young saddler’s apprentice, and their various specializations are very useful for my expedition.

In my will I have stipulated the necessary provisions should it be God’s will that I not see the end of this expedition. It is in the hands of Mr. Lynd. Should this come to pass then I want dear mother to make the same arrangements in her will as I have made in mine. I sent my journal to Dr. Nicholson and I only hope that it will at least make enough money to pay the debt that I owe him. Should this not come to pass then I hope to still be able to correct a mistake I made when making my will.

I hope that my dear beloved mother, whose birthday I silently observed on 9 November as I was riding in solitude across a vast plain in the Darling Downs, is still enjoying good health. Often, when I suddenly imagine myself at home, away from my present, so very different circumstances, and then imagine how she thinks back on her poor, wandering Ludwig, how much she wishes

she could see him alive one more time, tears stream down my face and I turn to our heavenly Father, who has so far so kindly provided for us, in prayer for her, for myself, and for all of us. After concluding this expedition I will return to Europe and pay you a visit; yet I would find it difficult to live in Germany or even Europe for good. I must return to the country of my traveling years, return to the beautiful, magnificent skies of Australia!

Farewell, brother-in-law, sister! Convey greetings to dear mother, convey greetings to all of my relatives and friends from your affectionate and loving

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/13.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.

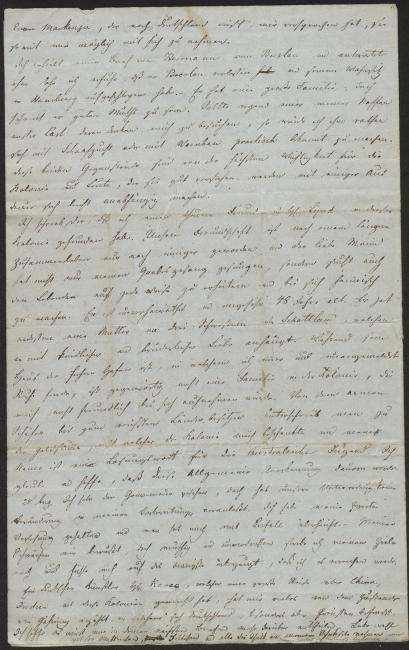

Sydney, 19 August 1846

My dearest brother-in-law,

Since my arrival from Port Essington I have been kept busy nearly constantly with composing the report on my expedition. Whereas I lived beneath God’s open sky for 15 months straight and almost never used a tent even on the occasional rainy day, I have hardly left the house for the last 4–5 months. My work is complete, has been proofed and copied, and will be sent to England in approximately 3 weeks. It is written in English, because I noted my observations in English and it would have taken me at least three times as long to write the work in German. I told you in my last letter that the colony gave me a gift of £1500, part of which, however, I will have to use for my new expedition. I intend to set out on this new journey in October, and when you read this letter I will once again be in the wilderness. I will probably derive some income from my work and my map as well, with which I intend to repay my debts to William. I hope to use the surplus to render dear mother’s last living days free of worries. Should Adolph not yet have been forced to sell father’s house, then I would pay the majority of his debts under the condition that dear mother derives an annuity from it for as long as she lives. — I dearly wish that father’s property continues to be associated with the Leichhardt family name. — I would certainly be glad to welcome Karl Barth in Australia; and I am certain that he could very well earn his bread here and make many friends, provided he is able and willing to accept conditions and circumstances for which his upbringing might perhaps not have prepared him. Yet it is hardly desirable that he arrives in Australia during my absence, and I will most likely be gone for 2 years. Two things are necessary to achieve independence in this country: persistence and some talent and humility.

It is unlikely that Karl will find work in his trade; it will be necessary to begin a completely different life. Knowledge of sheep farming and wine-growing would help him tremendously. For as long as I live in this country he would always have a home and a sanctuary, for I hope to make a home for myself after my next expedition. It is however possible that he might even obtain a position in his trade.

I have received demonstrations of utmost respect and consideration from all sides, and I am deeply moved to find the guiding hand of a benevolent Providence in this ever-changing life of wandering. Last night I gave a public lecture on my expedition and my audience granted me the loudest applause both before and after. Nothing gratifies me more than the knowledge that this general appreciation is not at all marred by jealousy, and even if jealousy should stir in the hearts of a few small-minded people, it is afraid to show itself in the light of day. We received some news about Sir Thomas Mitchell, who intends to find a way to the northwest coast of Australia. According to rather vague information he is at 22° latitude. I would like to receive more specific and more particular news from him before I embark on my expedition, which is longer and more dangerous than the last one because I intend to cross the entire continent on my way to Swan River. — This time I will take along mules and goats in addition to horses and bullocks. I think that the mules will prove to be very useful. I do not yet know whether I will receive government support or whether I will have to bear all costs myself. Yet this is rather irrelevant: I have the necessary resources and am willing to sacrifice my last cent to reach my goal. A new governor, Sir

Charles Fitzroy, has arrived, and I will almost certainly be introduced to him in a few days. He is said to be a liberal man and to have an interest in expeditions; I am therefore very hopeful to gain his support, since Captain King, who explored Australia’s coasts, is a good friend of mine and has proofed my work for me.

I am about to send my plant collection—or rather the pitiful remainder of the collection that I accumulated on my expedition—to my friend Gaetano Durando in Paris. He has continually displayed the greatest interest in my fate and I am certain that he will do whatever he can to make known any possibly new plants. I wish I could have organized my entire plant collection, yet I ran out of time and have to postpone doing so until after my next expedition.

The country has suffered from severe drought. This drought almost certainly proved rather beneficial to me, since I would have found it difficult to cross the big rivers and marshy areas on the Gulf of Carpentaria. However, it started to rain a few days ago, and I will most likely find enough water on my new journey. I am sorry that you will not be able to read the report on my expedition straight away, yet I am certain that it will be translated into German soon, since the discoveries will prove of the highest interest to geographers. I have sent you music and poetry that had been composed before and after my arrival. Two further pieces have been composed, of which a piece for harp by Mr. Marsh is exceptionally beautiful. Mr. Sylvester’s poem on my arrival is very nice and I wish that you could read a good and poetic German rendering. I hope that these items will not cause you any expenditures,

since Mr. Evan Mackenzie, who is traveling to Germany, has promised me to carry them as far as possible.

I received a letter from Hermann in Breslau and answered him before I learned that he had left Breslau and taken up residence in Hamburg. — He has a big family, yet appears to be in good spirits. Should any of my nephews aside from Carl wish to visit me I would advise them to gain some practical knowledge of sheep farming or wine-growing. These two matters are of the highest importance to the colony and people who know them well will, with a bit of persistence, easily attain independence.

I wrote to you that I have found a dear friend in Mr. Lynd in this colony. Our friendship has become an even closer one after living together for a while, and the lovely man not only sang my dirge, but also seeks to amuse the living man and make him feel at home in his house. He is unwed and approximately 48 years of age. He does, however, have a mother and three sisters in Scotland, to whom he is devoted with a childlike, brotherly love. While his house is the safe haven where I always find rest, even if dropping by unannounced, there is at present not one family in the colony that would not welcome me with open arms. Everyone, from the poor shepherd to the wealthy land owner, added their name to the sum of money with which the colony presented me, and my name is a watchword among Australia’s youth. I believe and hope that this general recognition will last.

28 August. I went to see the governor, but our talk did not cause me to change my preparations. I held my second lecture and was bathed in lavish applause. — Though aware of my weaknesses, I remain brave and undaunted in pursuit of my goal, and I am deeply convinced that I will accomplish it.

A German artist, Mr. Ravac, who was on a great journey across China, India, and these colonies, has told me a great deal about the state of fermenting unrest in which Germany, and especially Prussia, finds itself. I hope that you will tell me more about it in your next letters.

Farewell, convey my greetings to dear mother, Fettchen, and all who share an interest in my fate,

Most affectionately,

yours

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/12.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.