Last letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Darling Downs (22 February 1848)

Darling Downs, 22 February 1848

My dearest brother-in-law,

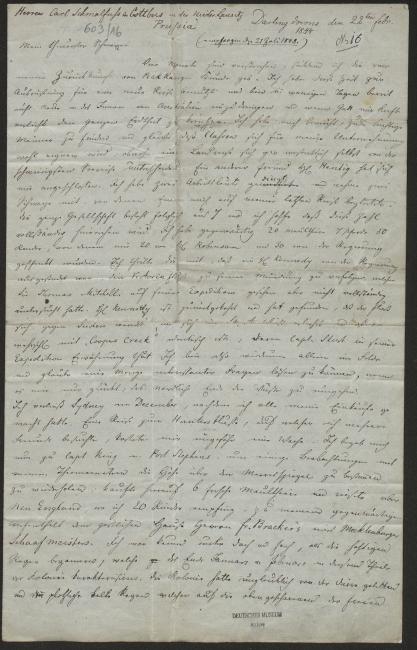

Four months have passed since I informed you about my return from Peak Range. I have used this time to make preparations for a new expedition, and in a few days will be once more ready to penetrate Australia’s interior, and, if God grants me the strength, to cross the entire continent. I have made an effort to find good, valiant men and believe that Classen will be well-suited to my endeavor, although a land expedition differs significantly from even the most trying of sea voyages. Another friend, Mr. Hentig, has also joined me. I have hired two workmen and will take two blacks along, one of whom accompanied me on my last journey. The entire company is thus comprised of 7 men and I hope that this number will prove entirely sufficient. At present I am in possession of 20 mules, 7 horses, and 50 bullocks, 20 of which were a gift from Mr. Robinson and 30 of which were gifted to me by the government. I told you that a Mr. Kennedy had been sent by the government to follow the Victoria River to its mouth, which Sir Thomas Mitchell had seen but not completely explored on his expedition. Mr. Kennedy has returned and has determined that the river turns southward and loses itself in Sturt’s desert, and that it is probably identical with “Coopers Creek,” which Captain Sturt mentions in his expedition [account]. I am therefore once again alone in the field and think that I can solve a great number of interesting questions if I only succeed in bypassing the northern tip of the desert.

I left Sydney in December, after I had made all my purchases. A trip to the Hunter River, where I went to visit several friends, delayed me by about a week. I then traveled to Captain King in Port Stephens in order to repeat a few earlier observations using my thermometer to determine the elevation above sea level; after that I bought 6 fresh mules and traveled through New England, where I picked up 20 bullocks, to my present location, the hospitable abode of Mr. Fr. Bracker, a master sheep farmer from Mecklenburg. I had scarcely gotten under shelter when the heavy rains commenced that are characteristic in this part of the colony from the end of January and through February. The colony had been suffering immensely from drought, and the sudden cold showers,

which rained down on New England’s freshly shorn flocks of sheep, standing utterly exposed to the night air, caused more damage than even the drought had. 100,000 sheep are said to have perished across the colony while the rains lasted. I myself witnessed the death of 800 in one night, when an entire flock of 1000 head sought shelter in stables and houses and feared neither the threats of people nor the dogs. As soon as the rain ended, and during the rains as well, all of nature, which had appeared almost dead to our eyes, tired of the monotonous yellow of withered vegetation, came to life, and the loveliest, sunny green enveloped the open forests and treeless pasture lands. This switch from an almost complete cessation of plant growth, from a desolate paralysis of nature, to the most luscious vegetation and an omnipresent, teeming world of insects reminds the eyewitness of Humboldt’s description of savannahs at the beginning of the rainy season.

As soon as the heaviest rains had passed and streams and rivers had become passable again I began to consolidate all of my possessions, which had been scattered almost across the entire Darling Downs, at Mr. Bracker’s in Rosenthal. I also had to look for such people as I wanted to take along with me. This is how I have spent my time for the last four weeks—almost constantly in the saddle and frequently dead tired. My provisions are likely to arrive here tomorrow or the day after, and this would allow me to set out next Monday, 28 February. I have had the pleasure to learn that the geographical society in London has awarded me one of their medals and that the geographical society in Paris has bestowed a similar honor upon me. I am of course delighted that such astute men deem me worthy of such an honor, yet I have never striven for honor but rather worked on behalf of science and science alone, and will continue to do so even if not one person in the world were to pay any attention to me. I am afraid to lose God’s blessing should I let my vanity take over and should the sincere, calm, painstaking quest for scientific knowledge become mixed up with ambitious striving for fame and recognition.

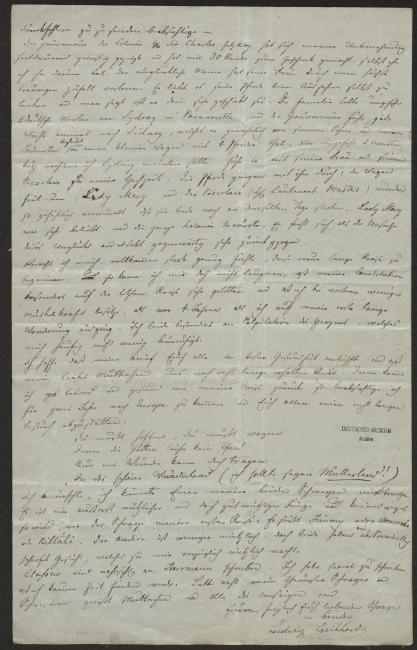

Mr. Durando of Paris writes that he has successfully received the scanty remains of my botanical collection and that Mr. Decaisne is

busy examining it. Even if my dried plants should not be suitable for determining new species, they should nevertheless prove interesting and useful for the botanical geography of New Holland. I have been very unfortunate with regard to my seeds, since none of the local institutions are suitable for growing and raising tropical plants. You might perhaps wonder why I did not send these collections to one of our German museums? The answer is that I conducted my studies of natural history primarily in English and French museums, and that I did not cultivate friendly relations with any of my compatriots during my youth, which would have obliged me to consider my friends first. Durando was a botanist and a very dear friend of mine. His circumstances were dire; I wanted to provide him with an opportunity to distinguish himself should my collection actually be of some value. This friendly tie to Durando compelled me to send the collection to him instead of sending it to a famous English or German botanist. Durando, however, has neither time nor confidence enough to undertake this project and has therefore given the collection to Mr. Descaisne [sic], who was always quite cordial and accommodating in his behavior toward me.

It was also quite a happy coincidence that I got to see my journal and my maps before departing. The maps are very nice and I am deeply indebted to Mr. Arrowsmith for transforming my rough sketches so beautifully. I will let others pass judgment on my book; it is a simple tale about our expedition and an equally simple description of the areas and things that I saw. If only the traveler is truthful, the scholar at home will thank him. He can never render a minor natural environment impressive and cannot describe the moderate mountain ranges of Australia as though they were the monumental ranges of America. I did not write intending to evoke maximum effect, and hardly thought it worth my while to employ the glowing language of a poetic huntsman to describe hunting kangaroos or emus. The public appears favorably inclined toward the book. At least it has been favorably reviewed in the papers. I would very much like to correct several very unfortunate typographical errors, and should Franciska truly intend to translate it, she would do well to contact Mr. Boone in London, to whom I intend to send

a list of these errors. —

The governor of the colony, Sir Charles FitzRoy, has always been favorably inclined toward my endeavor, and made me a present of 30 bullocks without me even requesting them. The unhappy man lost his wife through a most heartbreaking accident. He loves to take the reins of his horses when going out for a drive and it is said that he is very skilled. The family lived in Paramatta, about 3 German miles from Sydney, and the governor used to come to Sydney once a week, which he usually did in a small coach drawn by 4 horses, accompanied by his son and one servant. About 3 months ago, shortly after I had left Sydney, he drove to a wedding, along with his wife and secretary. The horses bolted on him, the coach tipped over, and Lady Mary and the secretary (Lieutenant Masters) sustained such severe injuries that both died the very same day. Lady Mary was very popular and the entire colony was in mourning. He blames himself for causing this tragedy and at present lives a very secluded life.

Although I most certainly feel strong enough to embark on this new, long expedition, I cannot, however, deny that my constitution has been seriously weakened, particularly on my latest expedition, and that I now have much less muscle strength than I did 4 years ago, when I embarked on my first long journey. In particular, I am suffering from heart palpitations, which frequently cause me quite a bit of worry.

I hope that my letter finds you all in the best of health and that my dear, beloved mother will stay with us for quite a long time yet. For if I return from my expedition alive and in good health, I intend to come to Europe for two years and to pay all of you a very long visit.

Faith thou needest, and must dare

Or the gods withhold their hand

Nought but miracle can bear

Man into the wonderland (I should say rather mother land!)

I wish I could take one of my two blacks home with me. He is a most useful and yet docile lad and not at all as wild as the black who came along on my first expedition. He is called Jimmy or Wommai or Kilalli. The other one is less useful. Yet both possess extremely sharp eyesight, which makes them of excellent use to me.

Claßen will probably write to Herrmann. I have so much yet to write that I will scarcely find time to do so myself. Farewell, my dearest brother-in-law and my sister, convey my greetings to dear mother and our entire family,

Most affectionately, your loving brother-in-law and brother

Ludwig Leichhardt

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/16.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.