On the trail of the Port Essington Expedition: Ludwig Leichhardt’s legacy in northern Australia

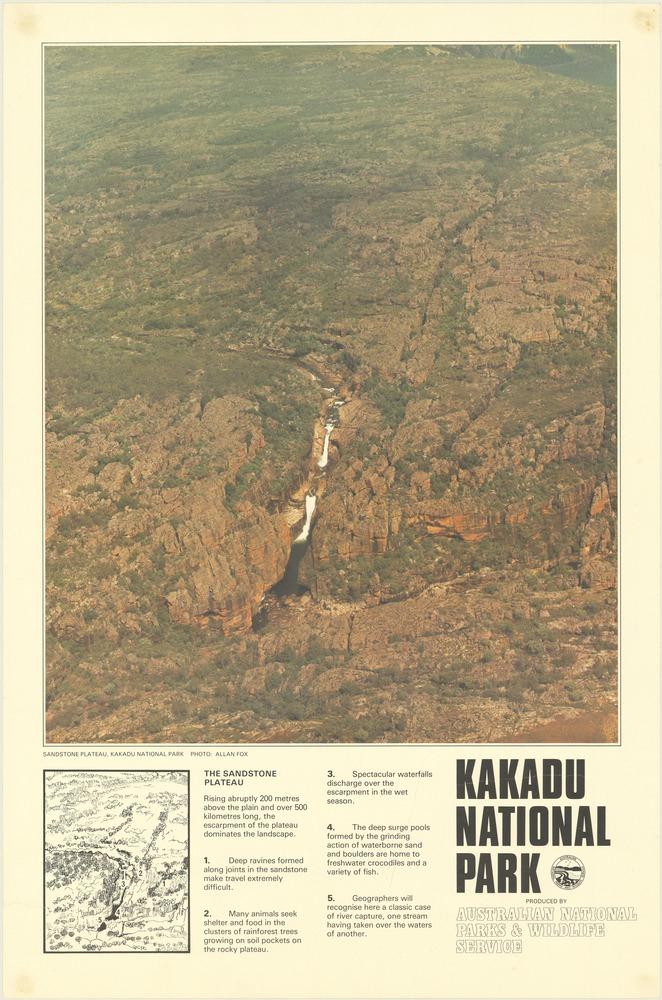

Advertisement for Kakadu National Park from the 1980s showing the sandstone plateau in Arnhem Land

Advertisement for Kakadu National Park from the 1980s showing the sandstone plateau in Arnhem Land

Paper by The Australian National Parks & Wildlife Service, Sydney, 1980s.

Courtesy of The State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Ludwig Leichhardt was the first European explorer to travel through the north of Australia; his journey is described in his Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia, from Moreton Bay to Port Essington. The first European reports about the northern region of the continent were based on observations made from the coast by seaborne voyagers. Men such as Matthew Flinders in 1803 or Phillip Parker King in 1818 were unimpressed with the view of this landscape from the ship. Leichhardt and his companions were the first Europeans to cross Arnhem Land and the Alligator Rivers region—now mostly part of Kakadu National Park—on their way to Port Essington. Leichhardt summed up his impressions in a letter to his brother-in-law (24 January 1846): “In places this area is very beautiful, in places … very mountainous.”

He was only a few weeks away from his destination when he came in view of the craggy, dry sandstone plateau, as he wrote in his travel journal on 11 November 1845:

I had a most disheartening, sickening view over a tremendously rocky country. A high land, composed of horizontal strata of sandstone, seemed to be literally hashed, leaving the remaining blocks in fantastic figures of every shape; and a green vegetation, crowding deceitfully within their fissures and gullies, and covering half of the difficulties which awaited us on our attempt to travel over it.

On 17 November 1845 the men came upon a cliff, which offered a view of a “beautiful valley, which lay before us like the promised land.” Three days later they had accomplished the difficult descent. From here the Alligator Rivers showed the way to the coast. One of the primary goals of the expedition, namely to find an overland route from the east coast to Port Essington, had been achieved. But only four years later the British trading post was abandoned.

Leichhardt’s grasshopper, Petasida ephippigera

Leichhardt’s grasshopper, Petasida ephippigera

Leichhardt’s description of the rich animal life of Australia lives on today in the insect commonly known as Leichhardt’s grasshopper. Leichhardt crossed the region of the South Alligator River shortly before the rainy season. The beginning of the rains was announced by huge flocks of bright red and blue grasshoppers, called aldjurr by the indigenous people.

Illustration by Ludwig Leichhardt, Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia, from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, London: Boone, 1847.

View source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Leichhardt’s travelogue has not lost its importance, however, and since its publication in 1847 it has been continuously reread and reinterpreted in the light of various historical contexts and interests. In addition to the landscape, flora, and fauna, Leichhardt describes his many encounters with the indigenous Australians—who traded peacefully with the expedition members and in some cases showed signs of previous contact with Europeans—as well as the multifarious cultural practices that bound them with the land. Leichhardt even mentions the art of the indigenous Australians in an entry dated 5 November 1845: “The remains of freshwater turtles were frequently noticed in the camps of the natives; and Mr. Calvert had seen one depicted with red ochre on the rocks. It is probable that this animal forms a considerable part of the food of the natives.”

When a major project was started in the 1960s to document the variety, imagery, and history of the indigenous rock paintings, the memory of the expedition in 1845 was awoken once more in connection with one of the most impressive rock painting galleries in Australia, Yuwunggayai. On the walls of a stone shelter, which extends for some 70 meters, are painted images in many styles dating back as far as 50,000 years—including the portrayal of an armed European.

Pina Giuliani, Research Officer, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, comments:

It is not possible to say exactly how many layers of large and colorful human and animal figures cover the main wall of Yuwunggayai. There are hundreds of paintings with image upon image and some obscure the view of paintings from earlier periods. A count by George Chaloupka, curator of rock art at the Northern Territory Museum from 1973 to 2011, of the most recent identifiable images revealed that there are at least 168 paintings of human figures and 212 animal representations. The only clearly visible paintings portraying Western contact are the European holding a gun and a stylized representation of a similar firearm.

The artist has portrayed the man with an animal head, a head like some of the spirit beings that appear in indigenous beliefs. He is shown fully clothed and holding a gun, as if preparing to hurl his weapon much like a spear. The site was first scientifically recorded in 1968 in an area known to balanda—white people—as the Deaf Adder Valley in Arnhem Land. Chaloupka was the second non-indigenous person to record this magnificent cultural site. While working with the indigenous owners of the estate and his indigenous mentors, Nipper Kapirigi and George Namingum of the Badmardi clan, he learnt that the local indigenous name for the site was Yuwunggayai (Pina Giuliani, personal correspondence with Heike Hartmann, 2014).

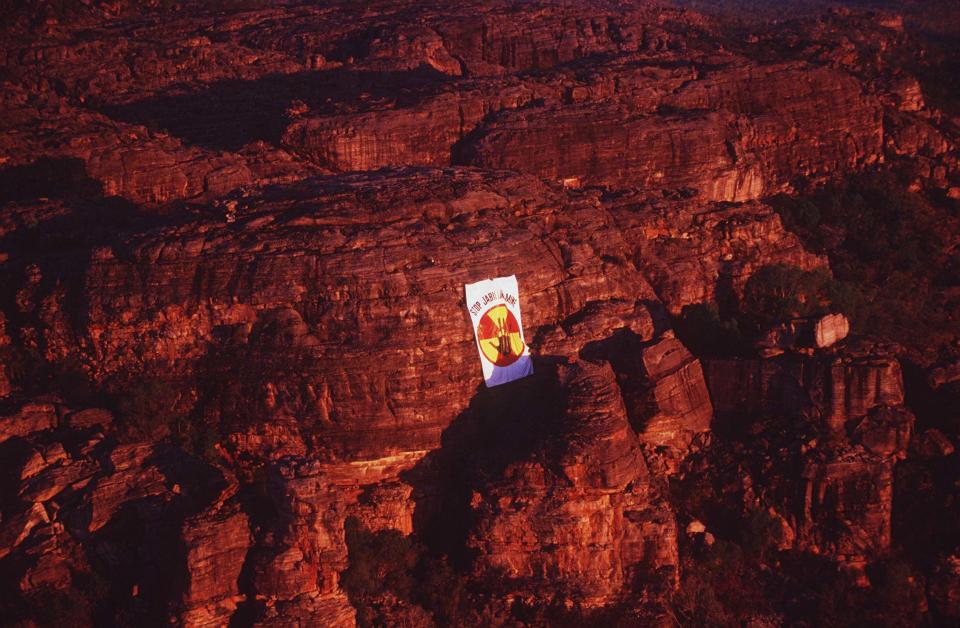

In addition to the indigenous name Yuwunggayai, Chaloupka called it the Leichhardt Gallery, and suggested that the man with the weapon was a portrait of the explorer or one of the other expedition members. Chaloupka hoped that this intentionally provocative and unsubstantiated interpretation would draw public attention to the rock painting and influence political decisions about the future of Arnhem Land, where large uranium deposits were discovered in the early 1970s. Under colonial law, the entire land was regarded as terra nullius and had been claimed by the British crown; at this time, the indigenous minority of Australia campaigned for an end to this, including the transfer of their traditional territories into their management and protection of these lands from exploitation. Future land use would have to involve a compromise between the interests of the uranium industry, indigenous land rights, environmental protection, and tourism. Chaloupka advocated the creation of a national park and the recognition of the land rights of indigenous owners and caretakers. Their support was decisive in bringing places of archeological, artistic, or spiritual significance onto the agenda.

Banner unfurled by Mirarr Traditional Owners within the Jabiluka Mineral Lease

Banner unfurled by Mirarr Traditional Owners within the Jabiluka Mineral Lease

Photograph by Sandy Scheltema, 1997.

Courtesy of The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, Jabiru.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

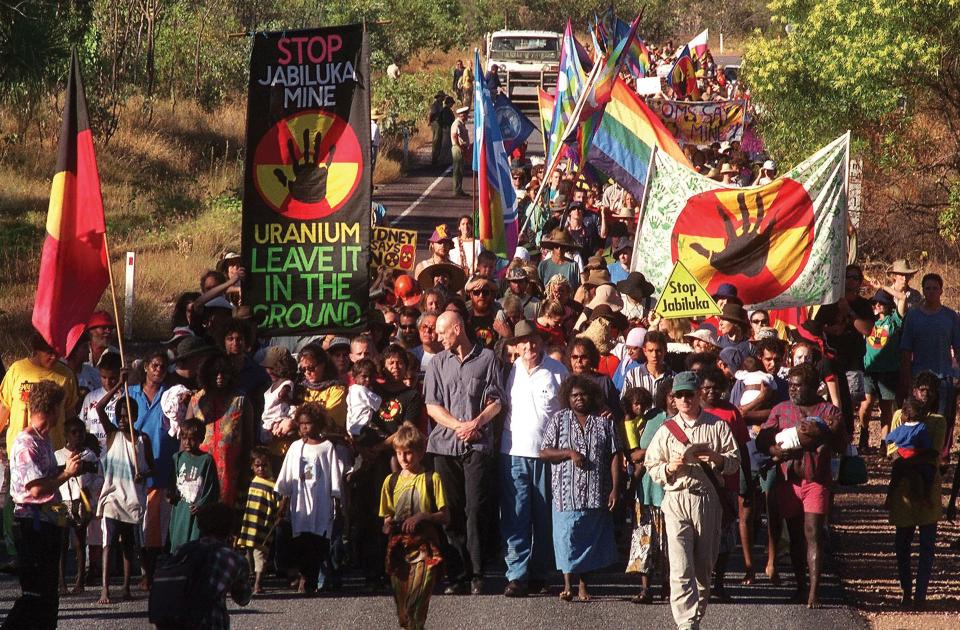

Mirarr Senior Traditional Owner Yvonne Margarula leads a protest against the Jabiluka mine in Kakadu National Park.

Mirarr Senior Traditional Owner Yvonne Margarula leads a protest against the Jabiluka mine in Kakadu National Park.

Photo by Clive Hyde, 1998.

Courtesy of The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, Jabiru.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

As the first European explorer in the region, Leichhardt lived on in the debates about the establishment of Kakadu National Park that started in the late 1960s. He made an appearance not only in the name of the gallery of rock paintings, but also of the nature reserve itself.

David Lawrence, Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, remarks:

In 1970 the Northern Territory administration appointed a planning team to investigate the area and prepare a plan of management. It was their report that first proposed the use of the name “Kakadu National Park.” The choice of name was based on fieldwork undertaken by anthropologist Baldwin Spencer in 1912 when he described the land between the East and South Alligator Rivers as the “tribal area of the Kakadu nation.” Following the report, the justification for the use of the name was further advanced by the fact that the Kakadu people helped Leichhardt in his journey to Port Essington in 1845. The Aboriginal presence was to be contained within the shadowy past, not included as part of a vital turning presence. The planning team reported that “the original people split into many groups and are almost extinct, although a few are known at Oenpelli Mission.” The “original people,” the plan of management stated, had left behind “in many galleries the wealth of primitive art for admiration and study by future generations” (David Lawrence, personal correspondence with Heike Hartmann, 2014).

The first section of Kakadu National Park became a protected area in 1979; between 1984 and 1991 additional neighboring territories were added. The Leichhardt Gallery is not part of the publicly accessible areas, but the indigenous traditional owners (the Aborigine people with claims on the land) have opened it for viewing as a tourist attraction.

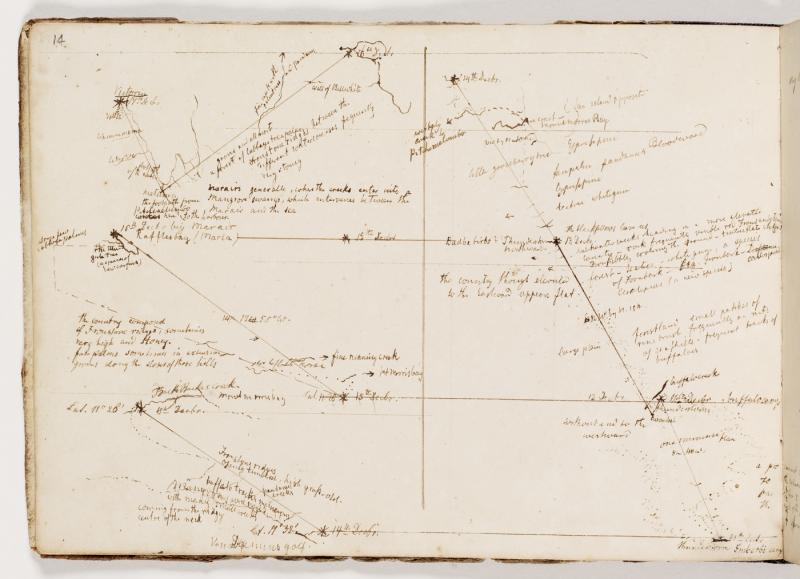

In his field notebook, Leichhardt made drawings of the region around his destination, Port Essington. His travel report describes encounters with Aborigines, who provided the expedition with water and food during the final stretch of the journey. Some of them understood a little English. They knew of the European settlement and could give Leichhardt directions.

In his field notebook, Leichhardt made drawings of the region around his destination, Port Essington. His travel report describes encounters with Aborigines, who provided the expedition with water and food during the final stretch of the journey. Some of them understood a little English. They knew of the European settlement and could give Leichhardt directions.

Hand-drawn map in Leichhardt’s field notebook by Ludwig Leichhardt, 1845.

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In one of his letters Leichhardt expresses the powerful colonial sentiment that his journey through the north of Australia was not just an act of mapping, but an act of creation, as though he had called the lands into existence by traveling through them: “It is a joy to observe how the land I wandered through emerges out of Australia’s unknown, blank interior” (letter to F. A. Schmalfuß, 18 April 1846). Leichhardt remarked in a letter to his brother-in-law about his work with a cartographer after his return from the Port Essington Expedition.

Today, these regions have become the site of conflicts resulting from different conceptions of the land, as represented by indigenous Australians and the colonial legacy. Leichhardt’s travels have gained new, unexpected relevance in connection with a number of these disputes.

In 1976 the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act created a legal basis for Aboriginal people to lay claim to lands that had been taken from them. One of the conditions was that they must be able to demonstrate a continuous connection with the land; this resulted in the reports of European explorers being reread with a view to uncovering indigenous history. In a number of cases from northern Australia, Leichhardt’s travelogues—particularly his many descriptions of encounters with Aborigines—were accepted as evidence of their settlement of the land far back into the past.

Leichhardt’s expedition brought the landscape of northern Australia onto European maps. Most of the names he gave to the landmarks—honoring expedition members, sponsors, friends, or based on events during his travels—are still in use today. Although Leichhardt is mostly recognized for his skills in navigation and descriptions of flora and fauna, his encounters with the indigenous population are also important for Australian society, for the various readings and rereadings of his writings take place on the contested terrain of Australian history.