Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, written aboard the ship Heroine (24 January 1846)

On board of the Heroine, an English ship sailing from Java to Sydney, 24 January 1845 [sic, for 1846]

My dearest brother-in-law,

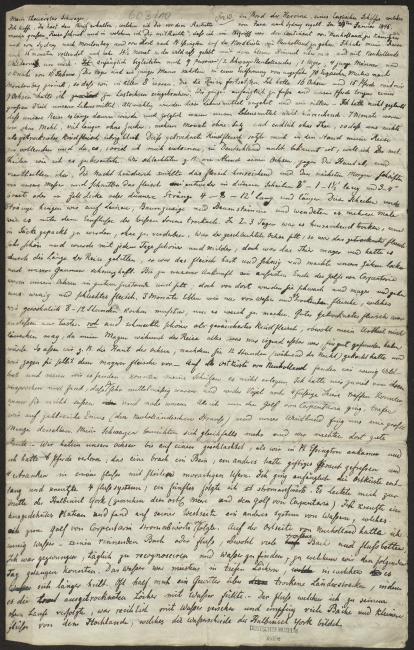

I hope that you have received the letter that I wrote to you before embarking on my great expedition and in which I told you that I was about to cross the continent of New Holland and to travel from Sydney to Moreton Bay and from there to Port Essington on the north coast of New Holland. After 16 months, I have completed my journey and spent 14½ months in the wilderness with the blue sky above me and the forests of New Holland around me. Initially 9 people accompanied me (2 black New Hollanders, 1 negro, 4 young men and 1 16 year-old youth). The negro und one young man returned to Moreton Bay after about 70 English miles, so that those of us who continued on the journey totaled 8 in number. I had brought 16 bullocks and 15 horses with me; 9 of the bullocks I had broken in to serve as pack animals. Initially we traveled on foot and our horses carried the majority of our provisions. We gradually consumed these provisions and took to the saddle. — I had not thought that our expedition would take so long and consequently our provisions proved insufficient. We went without flour for 7 months, even longer without sugar, several months without salt, and eventually ran out of tea, so that we had nothing left but dried beef. This dried beef allowed me to complete my expedition, and since it is unknown in Germany, if I remember correctly, I want to tell you how I prepared it. In the evening, say, we would slaughter a bullock, strip off its hide, and quarter it. Overnight the meat cooled sufficiently and the following morning we sharpened our knives and cut the meat either into thin slices 8”–1–1½’ long and 3–4” wide or into strips an inch or less thick and 4–8–12’ long or longer. We hung these slices and strips from ropes, tree branches, or tree trunks and turned them over several times as they dried beneath the hot sun. Within 2–3 days they had dried enough to be packed away into bags without running the risk of them spoiling. If the butchered bullock had been fat, the dried meat was very nice and became better and tenderer by the day; yet if the animal was lean and if it had suffered on account of the long duration of the expedition, the meat was very tough and stringy and loosened our teeth and made our gums ache. Our bullocks were in good condition and remained fat until we reached the outer edge of the Gulf of Carpentaria; yet after that point they became weak and gaunt and provided us with little meat, and that poor. For 3 months we subsisted on water and dried meat alone, which we usually had to cook for 8–12 hours to tenderize it. Good dried meat is best consumed raw, however, and tastes better than cured beef, although my assessment may perhaps not be trusted since my stomach would have declared everything that was at all edible to be tasty during the expedition. For example, we ate the bullock skin after it had stewed for 12 hours (overnight) and we even preferred it to the lean meat. — We encountered little game on the east coast of New Holland and if we saw any my marksmen were unable to bring it down. The hope I had placed in them turned to have been too high and I found them to be very mediocre and unable to hit either birds or quadruped animals if these were not resting or at close range. As I made my way around the Gulf of Carpentaria, we came across numerous emus (the New Holland ostrich) and our greyhound caught a great number of them for us. My blacks also began to make more of an effort and we came away from there with considerable booty. — When we arrived at Port Essington we had slaughtered all but one of our bullocks, and I had lost 6 horses: one had broken its leg, another had eaten poisonous weeds and 4 had drowned in a river with steep, muddy banks. I had initially traveled along the east coast and crossed 4 river systems; I followed a fifth one upstream. It led me to the middle of the York peninsula (between the eastern ocean and the Gulf of Carpentaria). I crossed a vast plateau and found a different water system on its west side, which I followed downstream toward the Gulf of Carpentaria. I found very little water on the east side of New Holland — no flowing streams or rivers, although there were many dry streams and riverbeds. Every day I was forced to go on reconnaissance missions to find sources of water that we would be able to reach the following day. More often than not, the water was in holes deep enough to retain it for a considerable amount of time. Thunderstorms frequently helped me survive dry stretches of land by filling the dried-up holes with water. — The river that I followed to its headwaters carried an abundance of water and absorbed a lot of streams and smaller rivers coming from the plateau that forms the watershed of the York peninsula.

I followed the Dawson starting at 16°–25° 30’, the system of the Mackenzie from 24° 40’–23° 15’, the Isaacks from 22° 30’–21° 30’, and the Suttor from 21° 30’–20° 35’; the latter merges with the Burdekin, which I followed from 20° 40’ up to 18° 30’; it comes from more of a north-eastern direction and since I was headed west I had to leave this beautiful river, which probably has its source 80–90 English miles higher up. I found the headwaters of the Lynd on the west side of the plateau, which I followed downstream (from 18°–16° 30’) where it ends in a bigger river, the Mitchell, which probably flows into the ocean at 15° 15’. I followed it to 15° 51’, and then left it since it led me too far north. I now turned west toward the ocean. Here between the Mitchell and the ocean I was attacked by blacks one evening after we had gone to sleep. God saved me, yet one of my companions, Mr. Gilbert, a bird collector, was killed by a spear piercing his heart, and two of my other companions, Mr. Calvert and Mr. Roper, were critically wounded. The blacks fled as soon as we fired a shot. I buried Mr. Gilbert and continued my travels after two days, heading south parallel to the east coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria. I crossed the Nassau, the Staaten, the Van Diemen, a smaller river that I named the Gilbert, and the Caron, and reached the head of the Gulf. I now turned toward WNW and crossed a good number of unknown rivers of significant size. It is possible that several of them share a common estuary. Whereas the east coast of the Gulf was beautiful and fertile, thickets of small trees or shrubs covered the country on the west side of the Gulf. At its head, I discovered extensive plains, which were frequently several miles long and broad. — The rivers, meanwhile, were surrounded by open forests and abundant grasslands on both sides. They were deep and broad as long as the tidewater flowed into them, yet shallow where the fresh water began. From the head of the Gulf I headed parallel to the coast toward Limmen Bight (15°), about fifteen to thirty miles from the coast, and reached the shores of the ocean at Limmen Bight. Our travels were very cumbersome here and our progress was very slow since the broad salt water rivers forced us to travel upstream until we found a place to ford them. The grass was meager, our daily marches often long and tiring, and we were forced to make camp several times without having found any sources of fresh water. On these occasions we had to hobble our horses and keep watch over our bullocks at night. Several times we found ourselves on the banks of a beautiful, wide river yet we had to content ourselves with the reflection of the water since it was salty and brackish. As a consequence of the long marches, bad pasture, and lack of water our bullocks grew thinner and weaker with every passing day, and one after the other they stopped walking, lay down, and thus declared that nothing whatsoever could induce it to take one more step. In such instances I left the animal behind and continued my travels until we reached water. I remained there the following day and sent my blacks back, who then slowly coaxed the animal toward the camp, where we slaughtered it — a month would have been hardly enough for it to regain the strength necessary to complete our journey. —

From Limmen Bight I continued my journey in a WNW direction and, after having crossed two mighty salt water rivers (which unite), I reached a freshwater river which I followed far upstream towards the west and WNW to the plateau of Arnheim’s Land. In places this area is very beautiful, in places, especially around the upper course of the river, very mountainous; I named this river the Roper, in honor of my companion. The plateau is flat, sandy, and covered by fairly open forest. On the plateau’s west side I happened upon the springs and headwaters of the South Alligator River, to which I descended from the plateau along a very difficult path. I followed the South Alligator River downstream until its waters became salty and then turned northward toward the East Alligator River. — Vast plains surround these rivers for as long as they carry salt water; rolling hills border these treeless plains at a distance of about ¾-

1 mile from the river. I reached the East Alligator River not far from its mouth, and since it is very wide and deep here I was forced to follow it upstream until I was able to cross it. After I accomplished this I continued my travels northward, found the narrow tongue of land of the Coburg peninsula with the help of some friendly blacks, and finally reached the English settlement of Port Essington in Victoria on 17 December 1845. You can easily imagine how I felt upon seeing houses and being welcomed by civilized people. I had concluded a 14½ month expedition through the wilderness, which was deemed by most to be not only highly dangerous but impossible given my resources. In spite of painful losses, I had managed to bring one bullock to Port Essington, so death by starvation had still been a good way off. Moreover, I still had eight horses and none of us had been forced to walk, which is very exhausting in this climate and most likely would have worn us out quickly.

I saw blacks frequently during my travel and interacted with them several times. With one exception, which cost Mr. Gilbert his life, they were always friendly. Whenever we happened upon blacks during our journey their fear of the horses and bullocks was so great that nothing could induce them to stay, they always ran off screaming and crying. Yet when we remained in the same spot for a longer amount of time to dry our meat, they saw us standing on our own two feet and concluded that we, although rather strange creatures, were in general very similar to them. Hence they gathered together and a crowd makes even a coward brave: after they had observed us at length from a distance and from atop the trees, some of their bravest warriors came closer and made signs conveying friendly intentions. I trustingly went to meet them, took several pieces of iron, metal rings, and so forth with me, and offered them as presents. They reciprocated instantly by giving me spears, clubs, and various other things that they wore as jewelry or as a sign of certain rights of seniority. At the head of the Gulf of Carpentaria and on its west side I thrice encountered black clans and they made clear that they had either seen Europeans or Malays from the Moluccas, Timor, Celebes, or Java before, since they knew our guns and our knives and even offered us their women for the latter.

On the South Alligator River we encountered for the first time blacks who knew of the settlement of whites in the Northwest. One had a piece of cloth, another an iron axe. On the East Alligator the blacks knew a few English words and we were delighted as we heard that one of them asked to learn our names. It appears that they thought us to be Malays. As we finally approached the peninsula, their clay pipes and knowledge of tobacco, rice, flour, and bread indicated that we were close to reaching our journey’s destination. These blacks were extremely friendly, and upon seeing that we had nothing to eat but tough dried meat, they brought us the mealy roots of a grass which had a very pleasant, sweet taste. We were fortunate enough to shoot down a buffalo at the neck of the peninsula, which provided us with meat again and saved the life of my last bullock. The thought of slaughtering this bullock made me quite out-of-sorts: it was my favorite and I had loaded it with my own hands throughout the entire expedition; it had been wild and fractious at first, yet became gradually tame and calm, although from time to time it hit gave me a friendly kick with its hind foot, which usually rendered me lame for several days. It now lives in Port Essington; I gave it as a present to Captain Macarthur, who is the commander of the outpost. He promised to take care of it. Captain Macarthur welcomed me very cordially and did everything in his power to make me forget all about the hardships of my journey. I completed my maps and my report on the expedition during my stay in Port Essington and luckily a ship from Singapore arrived, which contrary to custom was headed for Sydney by way of the Torres Strait.

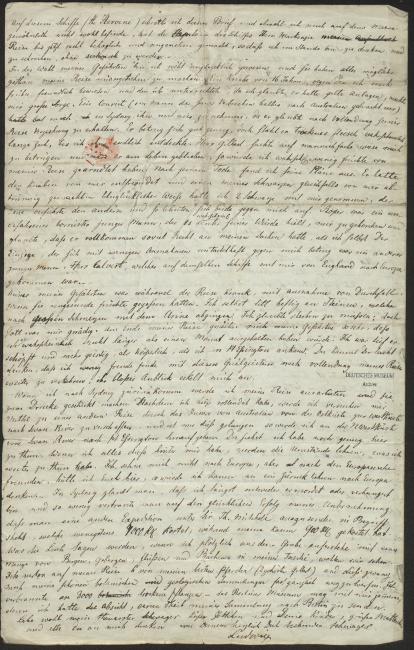

I am composing this letter aboard this ship (the Heroine) and although I usually feel ill at ease on the ocean, the captain of the ship, Mr. Mackenzie, has rendered my journey a pleasant and enjoyable one thus far, so that I am able to think and to write without becoming seasick.

I was rather unfortunate in my choice of companions and they did everything imaginable to render my travels unpleasant. A sixteen-year-old boy, to whom I had shown kindness in the past and whom I had taught since I believed that he had aptitude, proved a great worry to me. A convict (a man who had been sent to Australia on account of his crimes) asked me in Sydney to take him along, since he believed he would receive a pardon after completing the journey. He behaved well enough, yet he most likely stole dried meat for a long time before I finally caught him. Mr. Gilbert sought to cheat me in manifold ways and I would probably not have been able to enjoy many of the fruits of my labor during this expedition had he remained alive. I found out about his plans after his death. He had turned the boy against me, and had done likewise with one of my blacks. — Unfortunately I had taken 2 blacks along, the one led the other astray, and in the end both rebelled against me. Roper was an inexperienced, small-minded young man, who probably thought it beneath his dignity to obey me and believed that he had as much right to my belongings as I did myself. The only one whose behavior toward me, with a few exceptions, was beyond reproach was another young man, Mr. Calvert, who had crossed with me from England to Europe [sic, for New Holland] on the same ship.

None of my companions fell ill during the expedition, with the exception of diarrhea after they had eaten bad fruit. I myself suffered greatly from gall stones, which I, in great pain, passed with my urine. I thought I would die, yet God had mercy on me. Toward the end of my journey my companions tortured me so much that I probably would not have been able to stand it for much more than a month. I was completely exhausted, more mentally than physically, when I arrived at Port Essington. You can easily imagine that I find little joy in interacting with my tormentors after completing the expedition; the mere sight of them sickens me.

Upon my return to Sydney I will write an account of my expedition and prepare it to go to print. After completing this task, I will try to raise money for a different expedition through Australia’s interior, from the east to the west coast to Swan River. If I accomplish this, then I will travel along the northwest coast from Swan River to Port Essington. As you can see, I still have enough left to do here. When all of this is behind me, then my circumstances will guide me as to what more I shall do. I do not long for Europe, but I do for my European friends. If you were here I would hardly consider returning to Europe. — In Sydney it is believed that I have long since been killed or have starved to death, and so little did they trust in the happy success of my endeavor that they are about to launch another expedition headed by Sir Th. Mitchell, which will cost at least 7000 Rtl., whereas mine cost barely 900 Rtl. We shall see what the people say when I suddenly emerge from the grave with my pockets full of mountains, mountain ranges, rivers, and streams. I lost 6 of my best horses during my journey (2 belonged to Gilbert) and this forced me to throw away my beautiful botanical and geological collections almost entirely. I burned about 3000 dried plants—the Berlin Museum may join in my lamentations because I had intended to send a part of my collection to Berlin.

Farewell my dearest brother-in-law. Kiss Fettchen and your children, convey my greetings to dear mother and all who keep me in their thoughts,

Most affectionately,

your loving brother-in-law

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/10.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.