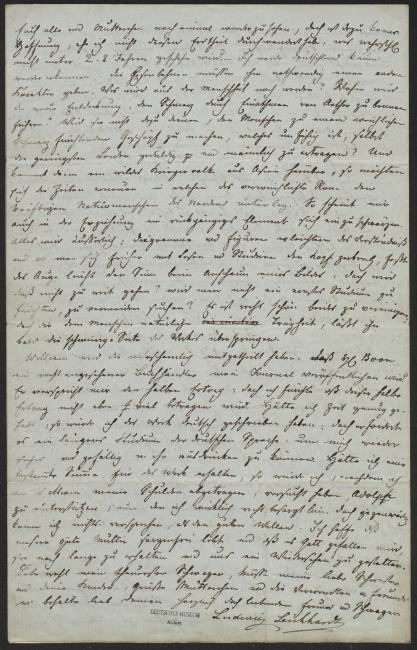

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Camden/Sydney (20 October 1847)

Camden/Sydney, 20 October 1847

At the house of William Macarthur

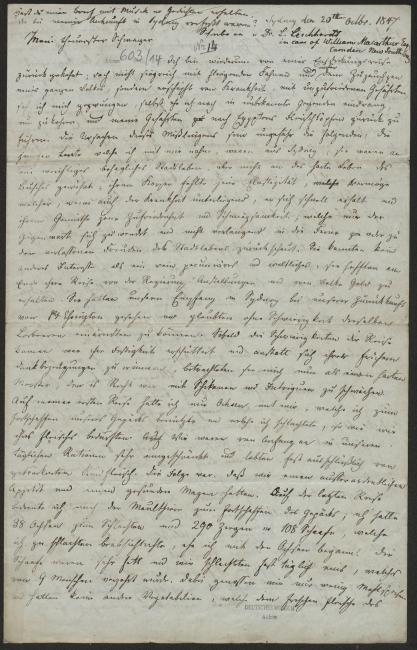

My dearest brother-in-law,

I have once more returned from my expedition, yet not victorious with flying banners, bathing in the jubilations of the people, but on account of exhaustion from disease and due to malcontent companions I was forced to return and to lead my companions back to the fleshpots of Egypt before I ever even had the chance to penetrate unknown areas. The reasons for this failure are more or less as follows: the young men that I had taken along with me were from Sydney; they were used to a soft, comfortable city existence but not the hard life in the bush; their bodies lacked the elasticity that allows someone to recover quickly even after having fallen ill, and their minds lacked the contentedness and flexibility that allows one to focus entirely on the present instead looking longingly into the future or back to the lost pleasures of city life. They were interested in nothing but purely pecuniary and mundane considerations: they hoped to receive government posts and obtain money from the people after completing the expedition. They had witnessed the welcome that we had received upon our return from Port Essington and thought they would be able to win similar laurels without difficulty. As soon as the hardships of the journey became apparent, their conviction was shaken, and instead of remembering their former words of gratitude they came to see me as a harsh master who they had a right to weaken by way of harassment and intrigues.

On my first expedition I brought along only bullocks, which I used for carrying our baggage and which I slaughtered whenever we were in need of meat. From the start we had to make do with very limited daily rations and subsisted almost exclusively on dried beef. We consequently developed a big appetite and our stomachs remained healthy. On my latest expedition I used mules for carrying our packs; for purposes of slaughtering I brought along 38 bullocks as well as 290 goats and 108 sheep, which I intended to slaughter ahead of the bullocks. The sheep were very fat and we slaughtered one almost every day, which was shared among 9 men. Moreover, we ate few flour-based dishes and had no vegetables that could have balanced out the fresh meat.

As a consequence of this diet of fresh, fat meat, our stomachs were frequently upset and our bodies more prone to infection. When the rainy season started, we traveled alongside flooded river banks for long stretches of time, slept on damp grounds every night, and a swollen river that we needed to cross finally forced us to remain in one spot for three weeks. Over the past year the entire colony has been abnormally wet and tertian fever occurred in places where it had hardly ever been known before. When we were finally able to cross the Mackenzie this disease had weakened my companions to such an extent that we had to rest on the opposite bank for another three weeks, until I finally tried to push onwards forcibly, which resulted in us covering a further distance of about 70 miles. My companions now became disgruntled; they were unwilling to exert even the smallest effort to assist me and one of my blacks, or, if they did anything at all, they did it badly and did more damage than good. Thus we lost our goats, our bullocks, and in the end even some of our mules and horses, and a hasty retreat was our only salvation. The fever had not caused me much suffering, yet on the return journey I was seized by rheumatism in my fingers, hands, elbow, back, and knees, and was so helpless that I was scarcely able to mount and dismount my horse. However, after I had spent about 14 days resting at Mr. Russel’s station in the Darling Downs, I felt strong enough to attempt a different expedition of about 5–600 miles, in order to determine the course of a river (the Condamine), and to explore the area that lay between my own path and Sir Thomas Mitchell’s. It took me about six weeks to complete this expedition and I completely recovered my health during it by exposing my ailing limbs to the burning rays of the Australian sun; these acted like a blistering plaster and alleviated the acute pains that even the slightest movement had heretofore caused me. I then returned to Sydney to make the necessary preparations for my new expedition.

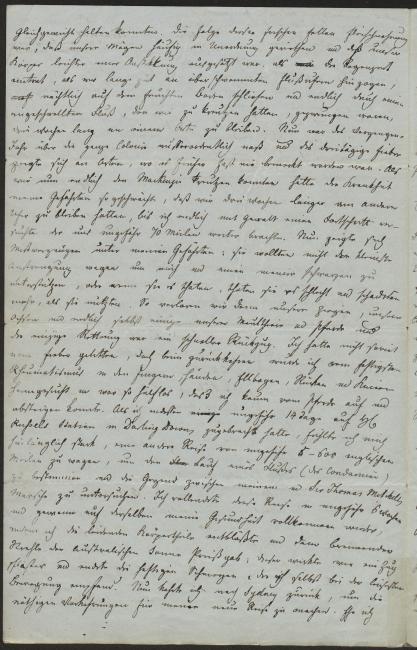

Before I left the Darling Downs I was delighted to learn that 5 of my runaway mules had returned after straying off course for about 600 miles, which saved me a considerable sum of money. I will have to spend approximately £200 on new equipment; my original expenditures totaled about £650, and thus the entire outlay for both the failed and the new expedition will amount to £850. This is a lot of money in Germany and quite a hefty sum here as well, yet I live for, I exist solely through my ventures and leave the future up to God. You gave me magnificent advice in your wonderful last letter, but I cannot follow it, it is not in my nature. An endless, indomitable drive compels me to study this natural environment and to solve this country’s mysteries. It is a lovely, complex field of study and if I had good companions I would roam Australia’s forests as happy as the son of an Irish king, yet to find competent companions is so extraordinarily difficult. For the most part only materialistic, small-minded, amoral young men approach me, since they have no other way of advancement. On my first expedition they were almost all still boys, with 2 exceptions, and therefore I was able to force those who rebelled against me to obey me once more. On my next expedition Mr. Classen will accompany me, who has been to almost all shores and crossed all oceans over the past 12 years, who is quite a well-educated young man, and who has suffered enough hardship so as to be sufficiently prepared for an expedition such as mine.

Mr. Lynd, my amiable host, has received orders to leave Sydney and to proceed to New Zealand, where the aborigines are making a large military presence necessary. I therefore have to look for another home, and although I can everywhere find hospitable accommodations for myself, I do require a safe place for my ever-increasing collections, where they will not only be sheltered from insects and the elements, but also easily accessible for whenever I have time to study them.

What you told me with regard to the intercession made by the gracious Princess Pückler is quite good and pleasing. I would very gladly be at peace with my native country and not run the risk of being incarcerated upon my return.

I wish I could see all of you and dear mother one more time, but there is no hope for that as long as I have not crossed this continent, which will most likely take two to three years. — I shall hardly be able to recognize Germany. The railroad will surely have given it a different character. Where will the new discovery of averting pain by inhaling ether lead? Will it not serve to transform men into soft, pain-shy creatures unable to endure even the slightest affliction with patience and manliness? And then, if a savage warrior people should invade from Asia, the times when effete Rome succumbed to the strong primitives from the north will be upon us once again. From my perspective, a regressive element seems to have entered educational practices as well. Everything is becoming outwardly-oriented; diagrams and figures facilitate comprehension, and whereas we racked our brains by reading and studying in the past, the eye now easily grasps meaning when beholding a picture. Yet is this not taking it a step too far? Will students not fear and try to avoid serious courses of study? It is admirable to combine both avenues of learning, yet man’s inherent idleness will soon induce him to skip the harder aspect of the work.

William has probably told you that Mr. Boon, a well-respected bookseller, will publish my journal. He has promised me half of the proceeds, yet I am afraid that this half of the profits will not amount to very much. If I had had the time, I would have composed the work in German but I would have to take some time to reacquaint myself with the German language before I could once more express myself in it with confidence and ease. Had I received a lump sum for the work I would have tried to help out Adolph, since I am truly worried, after paying off the debt I owe to William. Yet at present I cannot give any concrete assurances, aside from those of my good will. I hope that our dear mother is enjoying a worry-free life and that it pleases God to keep her for a long time yet and to allow us to see each other again.

Farewell, my dearest brother-in-law, give a kiss to my dear sister and your children, convey my greetings to dear mother and my relatives and friends, and keep me in your heart

Most affectionately, your loving friend and brother-in-law

Ludwig Leichhardt

[Post scripta at head of first page:] Did you receive my letter containing the music and poems that were composed upon my arrival in Sydney? Address your letters to

Dr. L. Leichhardt

in care of William Macarthur

Camden New South Wales

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/14.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.