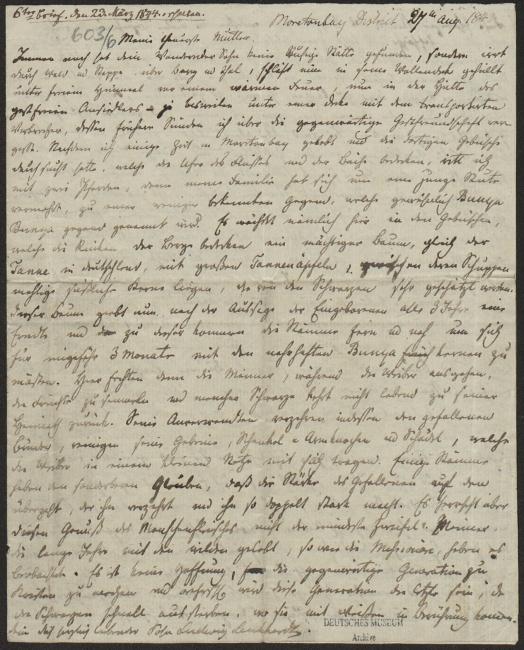

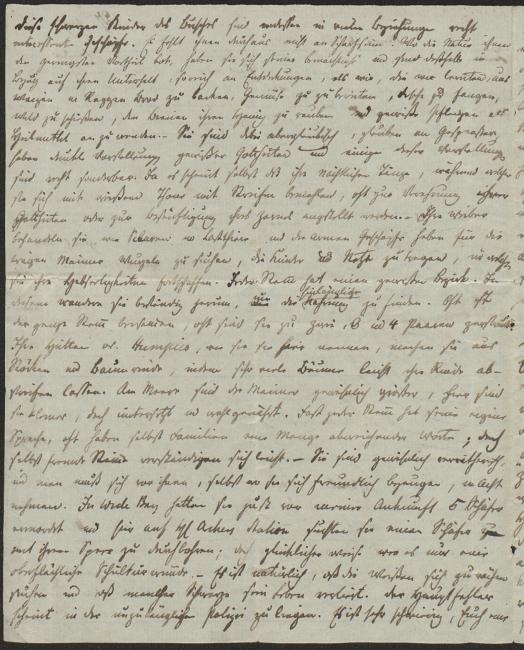

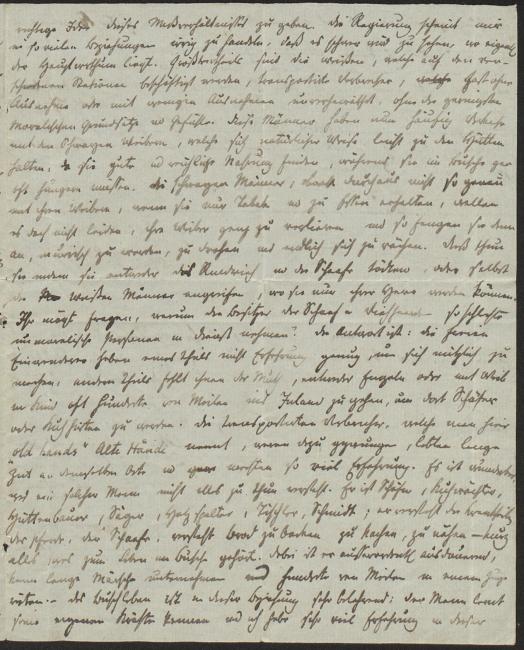

Letter to his mother, Charlotte Sophie Leichhardt, Moreton Bay (27 August 1843)

Moreton Bay District, 27 August 1843

My dearest mother,

Your wandering son has still not yet found a place for settling down, but roams across forests and plains, mountains and valleys, sleeping next to a warm fire beneath the clear sky wrapped in his woolen blanket one day, in the hut of a hospitable settler the next—indeed occasionally sharing the blanket of a transported convict, whose present hospitality makes me forget his past sins. After I had lived in Moreton Bay for a while and investigated the vegetation that covers the shores of the rivers and streams there, I took two horses—my family has by now been enlarged by a young mare—to a lesser-known region, customarily known as the Bunya Bunya district. You see, there’s a huge tree [with this name] that grows among the bushes that cover the ridges of the mountains; it is much like the fir tree of Germany and has large cones which contain harbor floury, sweet kernels between their scales and are highly valued by the blacks. According to the natives, this tree yields a harvest every 3 years and on this occasion clans arrive from near and far to gorge themselves on the nourishing Bunya kernels for approximately 3 months. At that time the men fight it out here, while the women go out to gather the fruits, and many a black man does not return to his home alive. His relatives, meanwhile, consume their slain brother, clean his bones—his thighs, arms, and skull—which the women then carry with them in small nets. Some tribes hold the curious belief that the power of the slain man passes on to whomever eats him and renders the latter twice as powerful. There is not a trace of doubt that this consumption of human flesh occurs; men, such as the missionaries who have spent long years living among the savages, have witnessed it. There is no hope of converting the present generation to Christianity and this generation will most likely be the last one, since the blacks are rapidly dying out wherever they come into contact with whites.

Then again, these black children of the bush are rather interesting creatures in many respects. They are certainly not lacking in intelligence. They seized the slightest advantages offered them by nature, and in terms of subsistence practices their discoveries are as abundant as our own, having learned to turn wheat and rye into bread, raise vegetables, catch fish, shoot game, rob bees of their honey, and use certain plants as medicinal remedies. — At the same time, they are superstitious, believe in ghosts, have dark conceptions about certain deities and some of these conceptions are rather peculiar. Indeed, it appears that their nightly dances, during which they paint stripes of white clay on themselves, are often performed for purposes of worshipping their deities or appeasing their anger. — They treat their women akin to slaves and pack animals and the poor creatures have to search out roots for their indolent men, have to carry the children, and the nets in which they transport their belongings. Every clan controls a certain district. They roam it continually to find sufficient food. At times the whole clan is gathered together, at other times they are scattered into groups of 2, 3, or 4. They construct their huts, or humpies, as they are called here, out of sticks and tree bark, since the barks of many trees can be stripped easily. Along the coast the men are commonly larger, here they are smaller, yet stocky and well-nourished. Almost every clan has its own language; frequently even among families there are a lot of varying words; yet even unacquainted clans manage to communicate with one another easily. — In general, these people are treacherous and one has to be cautious around them, even if they claim to be friendly. In Wide Bay they murdered 5 shepherds just before my arrival and here on Mr. Archer’s station they attempted to skewer a shepherd with their spears, yet fortunately he only sustained a superficial shoulder wound. — It is natural that the whites then seek revenge and that many a black loses his life. An inadequate police force seems to be the main problem. It is very difficult to convey an accurate picture of this disparity to you. To me, the

government appears to act erroneously in so many instances that it would be hard to determine what the primary mistake actually is. For the most part the whites employed at the various stations are transported convicts, almost without exception or with few exceptions unmarried, devoid of any moral principles or feelings. These men often engage in relations with the black women, who naturally stick close to the huts where they find good, ample food whereas they quite often suffer hunger in the bush. The black men, although not that strict with their women if only they receive tobacco and food, do not wish to lose their women completely and so their mood begins to sour, they utter threats, and finally seek revenge. They do this by either killing cattle or sheep, or by attacking white men outright whenever they can get them in their control. You may ask why the owners of the herds of cattle and sheep employ the services of such bad, amoral persons? The answer is: on the one hand the free settlers do not have enough experience to make themselves useful, on the other hand they lack the courage to migrate hundreds of miles inland, either alone or with wife and child, to make a living as a shepherd or cowherd there. Transported convicts, who are called “old hands” here, were forced to do so, lived in the same place for long periods of time, and thereby acquired a lot of experience. It is incredible what all such a man knows how to do. He is shepherd, cowboy, builder, sawyer, woodcutter, carpenter, blacksmith; he is knowledgeable about illnesses afflicting horses and sheep, knows how to bake bread, how to cook, how to sew —in short, all matters that life in the bush requires. At the same time he possesses extraordinary stamina, can march long distances and ride for hundreds of miles at a time. — In this regard life in the bush is highly educational; a man comes to appreciate his own strength and I have gathered a lot of experience in

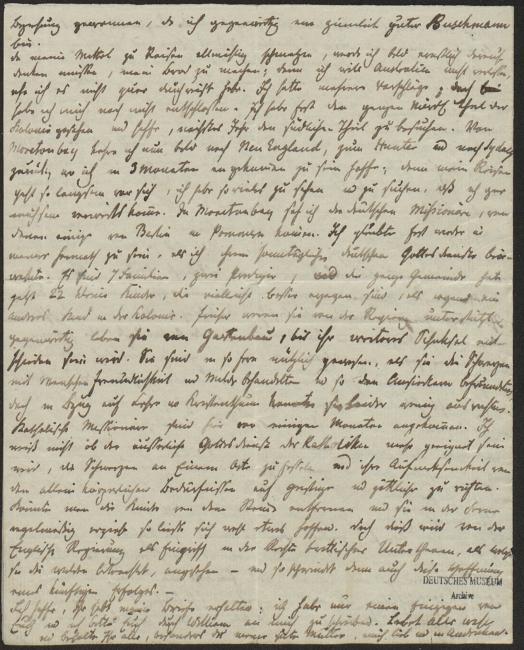

this respect, since I am at present quite a decent bushman.

Since my means for travel are gradually diminishing, I will soon have to seriously consider steady employment, because I do not want to leave Australia before I have traveled all across it. I received several proposals, though I have not yet come to a decision. I have seen almost the entire northern part of the colony and hope to visit the southern part next year. From Moreton Bay I will soon return to New England, the Hunter and Sydney, where I hope to arrive within 3 months; my headway is all but painstaking because my travels progress so slowly, and because I have so much to see and to seek. I saw German missionaries at Moreton Bay, some of whom come from Berlin and Pomerania. I almost believed myself at home again when I partook in their German worship service. There are 7 families, 2 ministers, and by now the whole congregation calls 22 small children their own, who are possibly better behaved than any other children in the colony. They were supported by the government in the past; at present they make a living by gardening until their further fate has been decided. They were useful insofar as they treated the blacks with humanity and kindness and thus rendered them friendly toward the settlers. Yet as concerns education and Christianity they were unfortunately unable to accomplish much. Catholic missionaries arrived here a few months ago. I do not know whether the formal worship service of the Catholics will be better suited to keep the blacks in one place and to direct their attention to matters of the mind and of God, away from mere physical needs. There would be some hope if, as a matter of routine, the children would be taken away from their clan and educated far away. Yet the English government regards this as an infringement on the rights of British subjects, which it considers the savages to be—and thusly this hope for future success is dwindling as well. —

I hope that you have received my letters; I only have one of yours and I am asking you to write to me by way of William. Farewell, all of you, and please keep me in your hearts and minds, especially you, my dear mother,

Most affectionately, your loving son,

Ludwig Leichhardt

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/6.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.