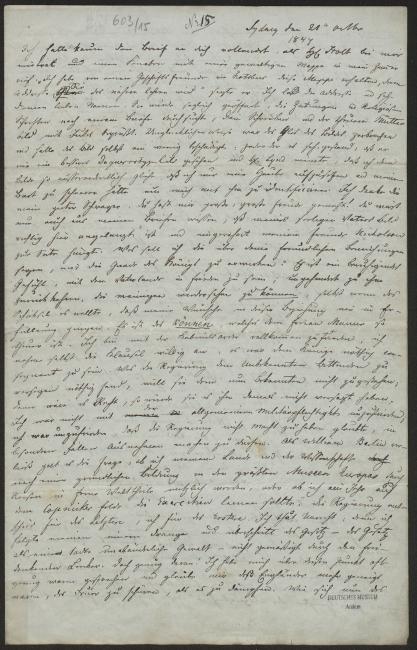

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Sydney (21 October 1847)

Sydney, 21 October 1847

I had scarcely finished my letter when Mr. Holt arrived and called a boy carrying an enormous portfolio into my room. He said: “I received this portfolio from a business partner in Cottbus, whose address will tell you the rest.” I read the address and recognized your dear name. I opened it at once, searched for a letter among the newspapers and religious literature, and rejoiced at seeing your letter and the picture of dear mother. Unfortunately the glass of the picture frame had shattered and damaged the picture itself a little. Everyone who beheld it said they had never seen a better daguerreotype, and Mr. Lynd opined I only had to don a bonnet and shave my beard and I would resemble it completely. I thank you, my dear brother-in-law. You have given me great, great pleasure! You will by now also have learned from my letters that the picture of my blessed father arrived here in one piece, was framed, and is hanging beside the one of my friend Nicholson. What can I tell you with regards to your gracious efforts to secure the king’s clemency on my behalf? It is a comforting feeling to be at peace with my native country, to be able return to it without impediments, to be able to see my family again, even if fate had decided that my wishes in this regard will never come true. This possibility is what a free man values so dearly. I am completely satisfied with the cabinet’s decree; I even willingly accede to the stipulation; it was necessary for the king to uphold the appearance of consistency. What the government deemed necessary to deny the unknown petitioner it now does not want to grant the newly famous man; because if the request had been right, [the government] would not have denied him it originally. I was not displeased with the institution of universal military service; I was displeased that the government did not think it had the power to grant exceptions in special cases. When William left Berlin the question arose whether I was to best serve my country and to serve science by receiving a thorough education in Europe’s biggest museums and by traveling to faraway corners of the globe, or whether I should spend a year learning how to exercise on the Köpenick parade grounds. The government decided on the latter, I on the former. I was in the wrong, because I followed my calling and violated the law—a law that is a dead, unchangeable power—not law moderated by a free-thinking ruler. But enough about that! I have often enough worked myself into a rage speaking on this topic and believe me when I tell you that the English were more inclined toward fanning the flame than extinguishing it. As the thought of

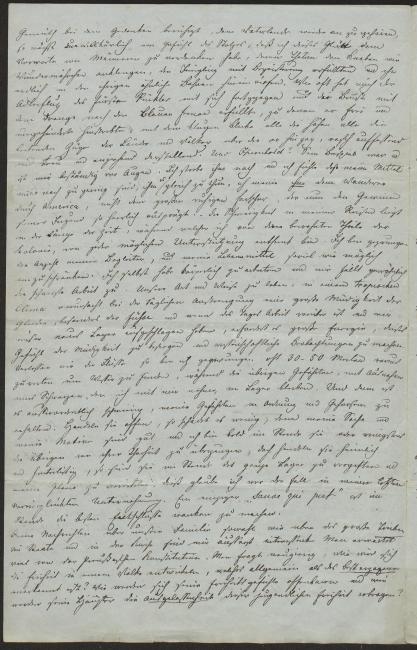

once again belonging to my native country calms my mind, an unbidden feeling of pride arises about the fact that I owe my happiness to the example of men whose deeds appeared like fairy tales to the boy, filled the youth with enthusiasm, and finally called on him to pursue a similar path. How often did the soaring adventures of Prince Pückler sweep me away and fill my breast with longing for blue faraway lands, which he sought out free and unhampered, quickly grasping and truthfully and pleasantly rendering all of the highlights and important characteristics of the lands and peoples he encountered. And Humboldt? His example will always serve as my guiding principle. I strive to be like him, but I feel that my means are still too limited to truly emulate him. By him I mean the wanderer through America, not the great, serene researcher who is now so admirably managing the success of his youth. — The difficulties I have on my expeditions are due to the amount of time that I spend away from the inhabited part of the colony, away from any possible support. I am forced to limit the number of my companions, as well as my provisions, as much as possible. I myself have to do physical labor and usually the hard work falls to me. In a tropical climate, our way of doing things causes our limbs, especially our feet, to grow very tired, and when the day’s work has been accomplished and we have made camp it requires a great deal of energy to overcome this tiredness and to make scientific observations. Whenever we stray from the vicinity of the rivers, I am forced to ride 30–50 miles ahead to find water, while the rest of the group, with the exception of one black man, who I take along, remains at camp. Then it is also extremely difficult to ensure order and obedience among my companions. Open defiance causes little harm, since my cause and my motives are just, and I am soon able to convince them, or at least the others, of their folly. Yet if they act secretly and insidiously, they are able to poison the entire camp and to frustrate all of my plans. I believe this to have been the case during my last, failed endeavor. A single “Sauve qui peut” is able to cause even those with a strong determination to falter.

I read your news about our family and about the vital happenings in state and church with the greatest interest. Much is expected of the Prussian constitution. Everyone is curious to see how freedom will develop among a people that is generally acknowledged to be the best-educated one. How will its ideas of liberty manifest themselves and how will its heads-of-state respond to the exuberance of this youthful freedom?

The Prussian is well-educated, but not in political matters; he still has much hard learning before him. Worthy representatives of the people’s interests, calm discussions, clear, powerful public speeches, a government willing to listen to the people’s representatives without prejudice, and preparedness to act according to the emergent will of the people rather than pursuing the interests of the few—these are all fruits of a plant that matures only slowly. —

I would willingly sign the profession of faith proposed by the German Catholics . The simple “I believe in Jesus Christ our Savior” utterly suffices; but I do not yet understand the value of believing in a universal Catholic Church! Is it that one sole universal church will be recognized across the entire globe? This would be desirable. Many of the sermons are extremely powerful and are a credit to both the German language and to the men who deliver them.

Yet why did you not tell me anything about the state of German poetry? Have all the German poets gone to sleep? Does the present time not lend itself to poetic expression? We were brought up on the idea that great times bring forth great poets and I cannot help but think that we live during great times. After three years of living in the wilderness I have re-read Schiller’s poems. What a magnificent, noble language! What noble feelings lived in the breast of this marvelous man! Music has never left as deep an impression on me as it did during my sea voyage from England to Sydney. It was a fierce night and the sea was quietly roaring beneath the keel of the steadily advancing ship. I had been listening to the muddled din for a long time when I suddenly got up and went to the cabin of my travel companion, Mr. Marsh, who was a great master harpist and who was improvising on this instrument when I entered. The orderly sounds, after the chaotic, dark roar of the wind and the waves, were so intense and pleasurable that they brought tears to my eyes. A similar feeling overcame me when I read Schiller again. How exceedingly true are the words of this visionary even though he himself never experienced this situation:

And as, after heartbreaking pain

And separation’s bitter smart

The child repentant seeks again

Upon his mother’s breast relief:

So to the thoughts of early days

When innocence was yet unstained

From foreign lands and foreign ways

Song brings the wanderer home, regained —

As regards the publication of my letters I only wish to tell you the following: I am of course pleased that educated men, not just the consideration and greater interest of a friend, deem them worthy of publication. Yet there are things I write to which I would not wish to see appear in print, especially as concerns the behavior of my travel companions. If I remember correctly, I complained bitterly about Gilbert, who was killed in my first expedition. I was completely justified in so doing, and if he had behaved as he did toward me as part of an official government-sponsored expedition, then he would have incurred severe punishment, as the example of Sir Thomas Mitchell’s latest expedition shows. I also shared my complaints with Mr. Gould, who had sent him; but Gilbert is dead and it would not please me if my complaints were to harm the memory of a very energetic traveler and collector who behaved valiantly in all other respects. —

You mentioned some nonsense about the possibly of me getting married, and that my dear niece Franciska is very excited about it! How did you hear of this? It is true that I loved a girl and that I even believed that she was not disinclined toward me. I did not talk to her about this matter, since I deemed it unsuitable to think of marriage when I was about to embark on a dangerous journey; yet I hoped that she, since she was still very young, would perhaps be willing to receive me after my return. This lovely girl is presently engaged and will be married in 2 months. Sic transit gloria mundi! Your poor brother-in-law would most likely despair and drown himself at once if thoughts of expeditions would not so completely fill his mind. I am afraid that my travels will take me beyond the age at which one wishes to marry and at which happy marriages are forged, and if my heart, in cold, proud composure closes itself off to love, then I shall have to face eternity alone. — —

written to Hermann about the possibility of finding a position in business for Karl Barth here. It would hardly be worth the trouble for him to come to Sydney for this. As a vintner or sheep farmer he would soon enough find a place and I believe that it would be most advisable to familiarize your son with these two branches should he ever feel the inclination to come live with his Uncle Ludwig in Australia. If it is at all in your power, make your children study chemistry; this science will prove useful to them under any circumstance. Cheer up Adolph! Don’t let him despair! As soon as I can be of assistance, I will help out, yet this promise does not mean that he can take it easy. I am sorry to hear that he has sold father’s house. Had I been able to sell the rights to my book for a lump sum, then I would have instructed William to assist Adolph; yet because this was not the case I do not know how much I income I will derive from the book.

Once again, adieu.

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/15.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.