Letter from Susanne Schmitt to the Oceans and Lakes Aquarium

Susanne Schmitt is a social and cultural anthropologist interested in design, emotion, atmosphere, and multispecies ethnography, currently at LMU Munich, Germany.

The Ocean and Lakes Aquarium is a fictional addressee.

Susanne Schmitt

Milchstraße 11

81543 München

Oceans and Lakes Aquarium

Preservation Junction 12

81764 Utopiaville

Munich, May 12th, 2014

Dear friends,

I am just getting around to having a thorough look through the pictures I took at the Aquarium last month. I picked a few and want to send them along, together with my most sincere thanks for your friendliness and your hospitality, and some thoughts.

Our conversations about emotion and the environment have been very important to me. We come from different backgrounds—marine biology, environmental studies and the like on the one hand, and anthropology on the other—and our understanding of what ‘nature’ and the environment could be are not the same. To the anthropologist, “nature” is a human phenomenon that cannot be accessed on its own terms (an does not, in fact, even exist independently) because we perceive of it in culture-bound ways. The environment, too, is everywhere; we are each other’s, along with everything else. “Nature begins where humans end” was a definition a wildlife biologist recently gave me when I asked him what his idea of nature was. Aquariums complicate those definitions of nature.

I keep thinking about our conversation about the aquarium as an emotional and emotive site, and as a locus of both the political and the phantasmatic. Now that I have met even more conservationists like you who consciously attend to the affective qualities of the stories they are telling and the images they are producing, and who try to talk about telling stories that are enabling rather than crushing, I want to look a bit closer at what kinds of stories and feelings materialize in aquariums when regarded through that lens.

Let me first say a few words on the two affective labels that float through this conversation: hope and optimism. Hope to me carries a gospel-like promise, a sensation against all odds. Admittedly, the odds are very bad, and we all know that. Hope has a quasi-religious connotation which is interesting because it is tied to a sensation of association, attachment, and absorption. There is a notion of religious energy, of dissolution of the individual and her boundaries into a larger community, into the social sphere around her, carried away completely by what Freud called an “oceanic feeling.” Incidentally or not, “immersion” is one of the creative paradigms of contemporary aquarium design also. Not only do all the different exhibits present different ecosystems and sub aquatic ambiances, but the whole experience of aquarium going is carefully designed to create an all-encompassing aquatic-oceanic (?) feeling. Visitors are made to feel completely em-placed, they both witness aquatic life and become absorbed by it.

Optimism, on the other hand, speaks of agency and possibility. It is directed towards the future. No aquarium visit is ever complete without the kind of bio-pedagogical advice that wants to enable visitors to save the oceans through their own effort. Optimism can be cruel though, writes Lauren Berlant: optimism is a form of attachment that may be betrayed (and so is hope, of course). The cruelness of optimism comes from the possibility that this attachment is a hurtful one if things do not come out as planned.

But back to the pictures. On top of the stack in front of me there is this one—a view of the meetings and functions room right behind the visitors’ entrance, aptly named “Tranquillity.”

The “Tranquillity Room,” Two Oceans Aquarium, Cape Town. The Tranquillity Room is a function room providing space for business meetings or private events such as weddings. The large window allows for a view onto the kelp forest.

The “Tranquillity Room,” Two Oceans Aquarium, Cape Town. The Tranquillity Room is a function room providing space for business meetings or private events such as weddings. The large window allows for a view onto the kelp forest.

Courtesy of Susanne Schmitt.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

When you are in the room, you can see right into the kelp forest. The giant seaweeds rhythmically sway from one side to the other. I could sit there for hours. The natural daylight shines in, painting streaks of sunlight across the tank. Fish swim by. The longer you look, the better you recognise their particular patterns of movement. Swarms form, move around together between the kelp. The larger fish swim more slowly. After a while, you recognise individual fish, and they recognise you, turning towards your figure behind the glass wall. A little later, I look up and see foam and sunlight, all the way up the kelp that grows upwards like a magic beanstalk. As I look down, I see sand and pebbles, and smaller forms of life, living their own existence without even knowing they are in what humans think is a kelp forest. I wonder if the life at the other side of the tank wall experiences their being there as tranquil? I doubt it, I believe it comes with all the stress and intensity that life usually brings, even in the absence of predators. Someone is always being eaten in the end.

Kelp forest. The Ocean Basket Kelp Forest Exhibit at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town. Kelp forests thrive along the South African Coast where the cold Atlantic seawater washes over the rocks and shores and sends nutrients up from the ground.

Kelp forest. The Ocean Basket Kelp Forest Exhibit at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town. Kelp forests thrive along the South African Coast where the cold Atlantic seawater washes over the rocks and shores and sends nutrients up from the ground.

Courtesy of Susanne Schmitt.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

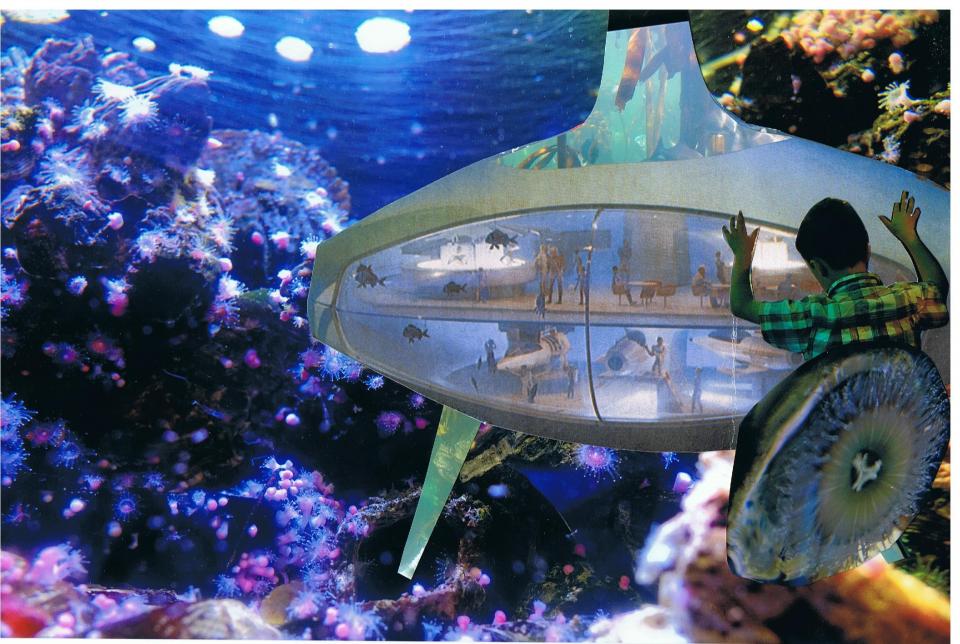

Narratives of doom and gloom are usually geared towards the future, and so are stories of hope and optimism—that things might get better or at least not worse. This picture, now one I glued to my notebook while I visited you, speaks to me not only of an interesting sense of presence, but also of a phantasm of the space age: human undersea habitation. The idea of humans living undersea has been a literary, architectural and scientific trope at different times when people tackled futurist ideas.

Undersea habitation presents itself in architectural dreams, in an aesthetic of the last frontier, both spaced out and ecologically sound. Most contemporary spin offs of those architectural dreams are resorts that evoke Captain Nemos’s holiday home, located near shore at the most beautiful diving locations.

Just look at that one: the draft of a library at the Poseidon Underwater Resort in Fiji. Although only a sketch by now, the way it looks—minimalist interior design and a window looking out, a submersed space, really speaks to me about the ways we organise and instrumentalise human–non/human oceanic entanglement through design. The sea here is both the actual event and the decorative framework for an interior. Just like the books in the shelves. What fascinates me most, however, is what you see when you look through the windows of these architectural sketches: happy, thriving marine life. Anything might happen here, all kinds of stories unfold, inside and outside. They unfold with the life in the ocean, inside the books on the shelves, they travel with the people who will come and stay there, and the people who made the computer animated design in the first place. Stories that bring about the whole complexity of feelings beyond doom and hope.

But what about funny stories, slightly depressing stories, cheesy stories, boring stories, never-ending stories? Stories whose tone shifts with every sentence? So many books, so many fish, so many empty seats, so many ways of telling a story beyond the hope and doom binary.

The image shows a 3D draft of the Poseidon Resort’s planned underwater library. Poseidon resort was envisioned as the world’s first sea floor resort located on a private island in Fiji. It has never been realized. Underwater hotels, however, remain touristic and architectural visions, with several companies currently working to build them.

The image shows a 3D draft of the Poseidon Resort’s planned underwater library. Poseidon resort was envisioned as the world’s first sea floor resort located on a private island in Fiji. It has never been realized. Underwater hotels, however, remain touristic and architectural visions, with several companies currently working to build them.

Image courtesy of the Poseidon Undersea Resort’s press kit.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Maybe the library has a book on Jacques Rougerie’s “Village sous-marin” (1973), architecture playing with organic forms and bionic design. Is this starfish-shaped dwelling and research site an expression of doom and gloom, or of optimism? What do you feel when you see it? Is it an expression of human expansionism and hybris? Of research that needs to be done so we can document and prevent further damage to the oceans? Or of attachment to the life aquatic?

The Village sous-marin, an underwater research and astronaut training center. French architect Jacques Rougerie has designed marine research labs and observatories, underwater habitats and villages. Inspired by bionics, futurism, and Jules Verne, he now plans to apply principles of underwater architecture to space exploration and habitation

The Village sous-marin, an underwater research and astronaut training center. French architect Jacques Rougerie has designed marine research labs and observatories, underwater habitats and villages. Inspired by bionics, futurism, and Jules Verne, he now plans to apply principles of underwater architecture to space exploration and habitation

Image courtesy of Créations Jacques Rougerie.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The two undersea dwelling sites that the Tranquillity Room makes me think of speak to the ways in which the oceans are imagined. In the popular imaginary, the oceanic is a site of excitement, beauty and well-being for the privileged, and a crucial resource, as well as a site of the threatening and the threatened. What I find so special about these phantasies of underwater living is their internal contradiction: they are often designed towards a future where living on dry land has become more and more difficult—the air polluted, the planet overcrowded, the soil poisoned. Yet the ocean we see when we look through these windows is clean. There are no dead reefs, no grey mud and empty ground where scurrying life should be, and swarms of plastic waste floating around. In those architectural fantasies, the very reason why humans would eventually abandon earth never eventuates.

Aquariums and other sites of audience-focused conservation have an educational mandate that aims at preventing us from ever having to abandon the earth. They educate through both information and feeling because they present that which should be conserved as worthy of protection because it feels good to look at. Their moral imperative comes from aesthetic impressions. They educate on the diversity of life and its potential futures. This future looks grim. Most aquariums I know try not to pretend that it is any different. But they show ecosystems that work. Aquarium exhibitions that truly reflected the state of the planet’s water systems would include lethal plastic trash, dead coral reefs killed by extensive tourism, industrial waste, and industrial fishing techniques that are not exactly sustainable. Both ways of perceiving of the aquatic and its future are real human ways of telling the story.

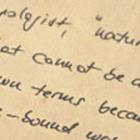

If you give in to them, if you dedicated yourself to them, aquariums exude a sense of presence, of immanence and submersion. Look at those two:

Making contact. A child leans on the a tank’s glass wall gazing inside and spreads out this hands at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town. A West Coast rock lobster (Jasus lalandii), a species endemic to the coast of Southern Africa and the Cape of Good Hope, looks back.

Making contact. A child leans on the a tank’s glass wall gazing inside and spreads out this hands at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town. A West Coast rock lobster (Jasus lalandii), a species endemic to the coast of Southern Africa and the Cape of Good Hope, looks back.

Courtesy of Susanne Schmitt.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Do you see how hands and antennae mirror each other in their movement? I see that, but I see the glass wall too. I come to believe that preservation of the environment is about empathy, about wondering what it would be like to have antennae and sit in a tank all day. Do they feel melancholy? Is the child simply spacing out, thinking nothing, looking for new details? Are they playing? Is he making plans to rescue the other life form behind the glass and let it run free into the ocean at the beach? Does he wonder what it will taste like? Has somebody told him this is nature? Do you think he is thinking about doom or hope? What do those abstract concepts even mean to any of those two? Nature, the environment, discourses of doom and gloom and hope are for those who share those concepts, who know what they mean and what they feel like.

Preservation carries the notion of presence. Presence never happens; it is already over when we write about it. It is a feeling. Emotions are positioning us towards doing. Since I read preservation in that way, I am more optimistic. How do you feel about that?

All the very best, Susanne

- Berlant, Karen. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

- Hayward, Eva. "Sensational Jellyfish: Aquarium Affects and the Matter of Immersion." Differences 23, no. 3 (2012): 161-96.