Letter from Richard Kool to Sam and Cohen

Richard Kool has a background in biology, ecology, and teaching, he is an associate professor at the School of Environmental Sustainability of the Royal Roads University in British Columbia, Canada.

Sam and Cohen are Richard Kool’s grandchildren.

Dear Sam and Cohen,

When you read this in 2040, the world will likely be quite different from the one I came into when I was born at the cusp of the twentieth century, in early January 1950.

While the great democracies had triumphed over militarism and fascism in a war that had ended five years before I was born, in our family, a grief was unarticulated but nonetheless present: most of our relatives had been murdered during the Holocaust, and no one was willing to talk openly about this. In spite of the economic boom of the 1950s and 60s, many Jewish families had a darkness, a gloom just under the surface, a despair about what had happened and an ever-present fear that if an attempt at annihilation had happened once before, it could happen again.

We don’t get to choose the times we are born into.

The fantasy trilogy The Lord of the Rings had this to say:

Frodo: I wish the Ring had never come to me. I wish none of this had happened.

Gandalf: So do all that come to see such times, but that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.

—The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001 film)

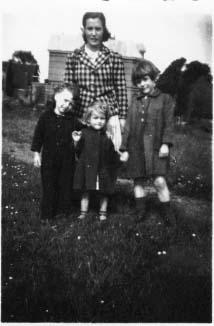

Hester Waas with the three young children she cared for while she was “hidden” in the Netherlands, taken some time in 1945.

Hester Waas with the three young children she cared for while she was “hidden” in the Netherlands, taken some time in 1945.

The original photo is in possession of Richard Kool.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Neither your great-great-grandmother or grandfather chose to be Jews in a time of annihilation nor did your great-grandmother Hester choose to be a hidden child, nor did I choose to carry the burden of survival and obligation coming from the Holocaust. “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.” And that is what you have to do with the time given you.

Dealing passively with doom and gloom is not something that is given to us. You two, like me, were not meant to walk on Earth. Inasmuch as my mother, your great-grandmother, was not meant to live, you and I were not meant to exist. We owe our lives to the people who didn’t simply moan about the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, but acted to save at least one Jewish girl’s life.

Our response to despair always has to be to do what we can do, where we are, with the tools available to us.

For many people of my generation, children of survivors of the Holocaust, the decision was to engage in work of tikkun olam, the Hebrew conception of “repair of the world.” The world we grew up in, the families we grew up in, were broken by a great tragedy and many of us took as our life’s work that of serving society as doctors, teachers, social workers, psychologists, writers and critics, environmental scientists and educators and more, in order, we hoped, to create conditions that would forever prevent the fascistic and xenophobic responses that led to the disaster that befell our families.

Perhaps in Hebrew school, we studied the tractate called Pirkei Avot, the Wisdom of the Fathers, where we would read:

Rabbi Tarfon says: The day is short and the task is great, and the laborers are lazy, and the wages are much and the Master is pressing.

He would say: It is not incumbent upon you to finish the work, but you are not free to abandon it.

What do we do with the time that is given to us? Rabbi Tarfon tells us that our own lives are short, we’d rather put off what needs to be done, and yet the rewards for deeds are significant. And most importantly, he reminds us we don’t have to do everything, but we have to do something, something to move towards the completion of the work whatever that work is. None of us can do all the work, whether it is solving the problems in the world, in our country, in our society, in our city, in our family or ourselves. Time is short, Tarfon tells us, and we must do what we can do, where we are, with the tools available to us.

Our tradition offers us models for doing what can be done. Many times in the Hebrew Bible, God calls people to action and accountability, and the appropriate response, uttered by Adam, Jacob, Isaac, Moses and other prophets and leaders was hineini, “here I am.” When faced by crisis, the tradition tells us “show up”; stand up and take the risk to do what needs to be done.

My favourite example of this comes from Exodus. After Pharaoh told the Israelites to leave Egypt and slavery, they head out into the desert and arrive at the sea: and looking back towards Egypt, they see a dust cloud—Pharaoh’s army coming to bring them back to slavery. Some Israelites think that perhaps slavery wasn’t so bad and say to Moses “Let us alone that we may serve Egypt! Indeed, better for us to serve Egypt than our dying in the wilderness.” In Exodus 14:21, Moses stretches out his hand over the sea, the waters split, and the Israelites scurry to safety, leaving Pharaoh and the Egyptian army to drown as the waters reconnect. But the rabbi’s ancient commentaries say that, with the Egyptian army on its way, the Israelites stood there on the shores and waited for something to happen and nothing happened until a young man, a prince of the tribe of Judah, a young man named Nachshon, walked into the water. He walked in having no idea as to what would happen, but he knew that he was not going to go back to slavery. He walked into the water with a faith based on what he had just experienced, that of his God allowing him to walk out of Egypt from slavery to freedom, and that faith was being translated into action as he walked up to his knees, his waist, his shoulders, his chin, and up to his nostrils. Walking his prayer into the danger and uncertainty of the sea and away from slavery and oppression, he walked into the water … and then the seas parted.

In the face of fear and a sense of doom, Nachshon walked into the sea and the Israelites followed, walking from slavery to the uncertain freedom we all continue to live in even today.

Our tradition is one of deeds as being more important than faith, of action being more important than endless study attempting to gain complete understanding. A month after Nachshon walked into the water, the Israelites were at Mount Sinai. There, Moses presents the Covenant, a new law we call the Ten Commandments, a new way of seeing and understanding the world, and this new law he offers to the Israelites just as they begin their wanderings toward freedom, a freedom that the French-Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas describes as a “difficult freedom.”

Why difficult? Because on hearing the Revelation at Sinai, the people said “Na’aseh V’nishma”—we will do and we will then understand (Exodus 24:7).

The difficult freedom of Levinas is that the Jewish people promised to do before they understood, accepting that real knowledge comes from the deed and not from reason alone. They accepted the difficult tension that comes from acting on inadequate and incomplete knowledge, the tension that comes from knowing that your deeds might not be correct and you’re only going to learn that through the doing. The temptation of temptations, according to Levinas, is the desire for security in knowledge prior to the risk of action. At times, we have to confront the necessity of acting with necessarily incomplete understanding instead of putting off what needs to be done until we are sure that our knowledge is complete, which of course it will never be.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (second from right) and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. (center) participating in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on March 21, 1965

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (second from right) and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. (center) participating in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on March 21, 1965

Used with kind permission of Susannah Heschel. View source.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

This emphasis on the doing of deeds—moral and/or sacred deeds—runs as a distinguished thread throughout both Jewish sacred and secular writings. In fact, the twentieth-century scholar Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote that “Jewish law is, in a sense, a science of deeds” (Heschel 1955, 292). The passage from the prophet Micah (6:8)—“What does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with your God”—is emblematic of this concern with deed. To the rabbis, this passage is the sum of the Law in a single verse: note that there is nothing here to tell you what you must know! The only injunctions here are what you must do; there is no call to faith, only to action.

The world you will live in is not something I can imagine, although I am sure of some things: the climate will be warmer, sea levels will be higher, there will be fewer species and more competition over certain natural resources that will become increasingly scarce. The issues that you may have to deal with will be large and complex and won’t be solvable by one person, or even a group of people at one time, but will likely take many people lots of work over much time, generations perhaps. My work to engage as a teacher in tikkun olam will not be completed: my efforts will not repair the broken and damaged world. Neither will your efforts. Yet our tradition tells us that we have no choice but to be part of the solution. How you are part of that solution is up to you; how you organize your family and community and society will be a reflection of your intellect and skill.

I have always felt the only antidote to despair is action.

Viktor Frankl, a survivor of the death camps, wrote that, based on his experience of life under totally extreme circumstances, no matter what situation we are in we can find meaning in our life even if not hope for the future “by creating a work or doing a deed; by experiencing something or encountering someone; and by the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering” and that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

Your ability to choose your attitude in the face of difficult situations is yours to exercise. The history we are part of gives us guidance and can instill in us a sense of obligation: we are not to succumb to despair but, as the prophet Moses tells us just before his death, to always choose life.