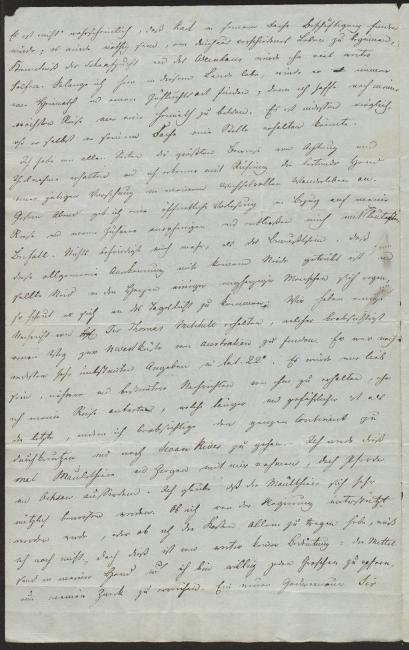

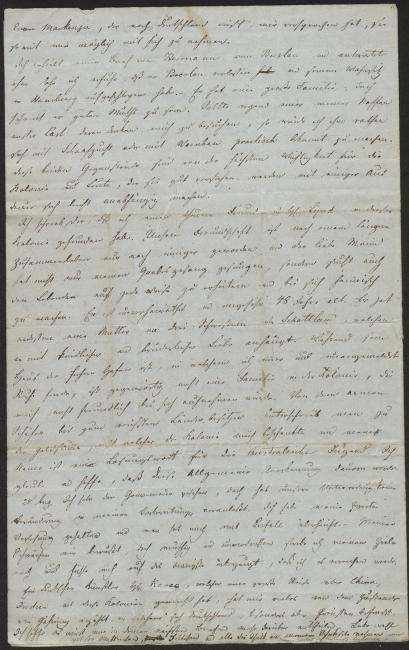

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Sydney (19 August 1846)

Sydney, 19 August 1846

My dearest brother-in-law,

Since my arrival from Port Essington I have been kept busy nearly constantly with composing the report on my expedition. Whereas I lived beneath God’s open sky for 15 months straight and almost never used a tent even on the occasional rainy day, I have hardly left the house for the last 4–5 months. My work is complete, has been proofed and copied, and will be sent to England in approximately 3 weeks. It is written in English, because I noted my observations in English and it would have taken me at least three times as long to write the work in German. I told you in my last letter that the colony gave me a gift of £1500, part of which, however, I will have to use for my new expedition. I intend to set out on this new journey in October, and when you read this letter I will once again be in the wilderness. I will probably derive some income from my work and my map as well, with which I intend to repay my debts to William. I hope to use the surplus to render dear mother’s last living days free of worries. Should Adolph not yet have been forced to sell father’s house, then I would pay the majority of his debts under the condition that dear mother derives an annuity from it for as long as she lives. — I dearly wish that father’s property continues to be associated with the Leichhardt family name. — I would certainly be glad to welcome Karl Barth in Australia; and I am certain that he could very well earn his bread here and make many friends, provided he is able and willing to accept conditions and circumstances for which his upbringing might perhaps not have prepared him. Yet it is hardly desirable that he arrives in Australia during my absence, and I will most likely be gone for 2 years. Two things are necessary to achieve independence in this country: persistence and some talent and humility.

It is unlikely that Karl will find work in his trade; it will be necessary to begin a completely different life. Knowledge of sheep farming and wine-growing would help him tremendously. For as long as I live in this country he would always have a home and a sanctuary, for I hope to make a home for myself after my next expedition. It is however possible that he might even obtain a position in his trade.

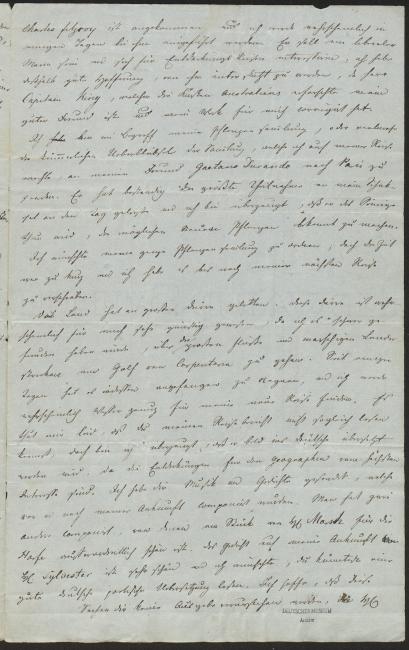

I have received demonstrations of utmost respect and consideration from all sides, and I am deeply moved to find the guiding hand of a benevolent Providence in this ever-changing life of wandering. Last night I gave a public lecture on my expedition and my audience granted me the loudest applause both before and after. Nothing gratifies me more than the knowledge that this general appreciation is not at all marred by jealousy, and even if jealousy should stir in the hearts of a few small-minded people, it is afraid to show itself in the light of day. We received some news about Sir Thomas Mitchell, who intends to find a way to the northwest coast of Australia. According to rather vague information he is at 22° latitude. I would like to receive more specific and more particular news from him before I embark on my expedition, which is longer and more dangerous than the last one because I intend to cross the entire continent on my way to Swan River. — This time I will take along mules and goats in addition to horses and bullocks. I think that the mules will prove to be very useful. I do not yet know whether I will receive government support or whether I will have to bear all costs myself. Yet this is rather irrelevant: I have the necessary resources and am willing to sacrifice my last cent to reach my goal. A new governor, Sir

Charles Fitzroy, has arrived, and I will almost certainly be introduced to him in a few days. He is said to be a liberal man and to have an interest in expeditions; I am therefore very hopeful to gain his support, since Captain King, who explored Australia’s coasts, is a good friend of mine and has proofed my work for me.

I am about to send my plant collection—or rather the pitiful remainder of the collection that I accumulated on my expedition—to my friend Gaetano Durando in Paris. He has continually displayed the greatest interest in my fate and I am certain that he will do whatever he can to make known any possibly new plants. I wish I could have organized my entire plant collection, yet I ran out of time and have to postpone doing so until after my next expedition.

The country has suffered from severe drought. This drought almost certainly proved rather beneficial to me, since I would have found it difficult to cross the big rivers and marshy areas on the Gulf of Carpentaria. However, it started to rain a few days ago, and I will most likely find enough water on my new journey. I am sorry that you will not be able to read the report on my expedition straight away, yet I am certain that it will be translated into German soon, since the discoveries will prove of the highest interest to geographers. I have sent you music and poetry that had been composed before and after my arrival. Two further pieces have been composed, of which a piece for harp by Mr. Marsh is exceptionally beautiful. Mr. Sylvester’s poem on my arrival is very nice and I wish that you could read a good and poetic German rendering. I hope that these items will not cause you any expenditures,

since Mr. Evan Mackenzie, who is traveling to Germany, has promised me to carry them as far as possible.

I received a letter from Hermann in Breslau and answered him before I learned that he had left Breslau and taken up residence in Hamburg. — He has a big family, yet appears to be in good spirits. Should any of my nephews aside from Carl wish to visit me I would advise them to gain some practical knowledge of sheep farming or wine-growing. These two matters are of the highest importance to the colony and people who know them well will, with a bit of persistence, easily attain independence.

I wrote to you that I have found a dear friend in Mr. Lynd in this colony. Our friendship has become an even closer one after living together for a while, and the lovely man not only sang my dirge, but also seeks to amuse the living man and make him feel at home in his house. He is unwed and approximately 48 years of age. He does, however, have a mother and three sisters in Scotland, to whom he is devoted with a childlike, brotherly love. While his house is the safe haven where I always find rest, even if dropping by unannounced, there is at present not one family in the colony that would not welcome me with open arms. Everyone, from the poor shepherd to the wealthy land owner, added their name to the sum of money with which the colony presented me, and my name is a watchword among Australia’s youth. I believe and hope that this general recognition will last.

28 August. I went to see the governor, but our talk did not cause me to change my preparations. I held my second lecture and was bathed in lavish applause. — Though aware of my weaknesses, I remain brave and undaunted in pursuit of my goal, and I am deeply convinced that I will accomplish it.

A German artist, Mr. Ravac, who was on a great journey across China, India, and these colonies, has told me a great deal about the state of fermenting unrest in which Germany, and especially Prussia, finds itself. I hope that you will tell me more about it in your next letters.

Farewell, convey my greetings to dear mother, Fettchen, and all who share an interest in my fate,

Most affectionately,

yours

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/12.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.