Mensch, Tier und Natur – Vorstellungen natürlicher, harmonischer (Ko-)Existenz

Mensch, Tier und Natur – Vorstellungen natürlicher, harmonischer (Ko-)Existenz

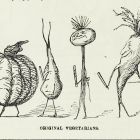

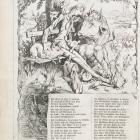

In the nineteenth century, there was much debate about the question of which way of living could be regarded as “natural.” Caricatures on vegetarianism mock ideas of the “natural” relationship between animal and man, and draft utopian as well as dystopian visions of a vegetarian future. This is from the German version of “Satirical Glimpses of the Cultural History of Vegetarianism.” For the English-language version of this exhibition, click here.