“You Are What You Eat”: Stupid Vegetables and the Charm of the New

The first German satire magazines were published in 1848, made possible by a temporary liberalization of censorship resulting from the German revolutions of 1848–49. By that time, the English magazine Punch, founded in 1841, was already mocking the vegetarian movement, which had gained a foothold in England some decades earlier than in Germany.

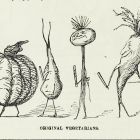

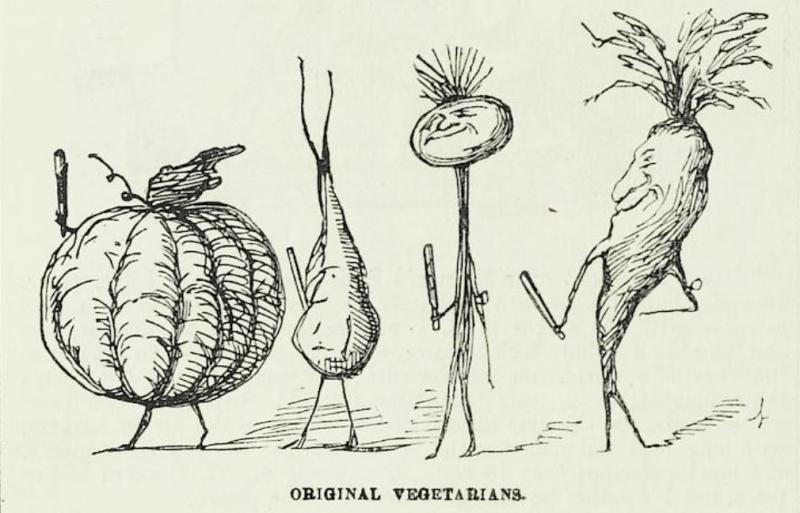

Original Vegetarians. Unknown artist, 1848.

Original Vegetarians. Unknown artist, 1848.

Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.

Originally published in Punch 15 (1848): 182.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This early cartoon, entitled Original Vegetarians, served as an illustration to a short text, The Vegetarian Movement, which satirically announces a large, well-organized, and strict vegetarian movement. The mere idea that people deliberately feed on plants (vegetables) alone caused a lot of amusement. True to the motto “You are what you eat,” vegetarians are here—and many times thereafter—portrayed as vegetables. The human faces and figures have been transformed into a pumpkin and various other root vegetables: the peaceful parade invites their physiognomical interpretation as harmless, or even stupid contemporaries (“stupid vegetables”). These portraits are inspired in style by Honoré Daumier’s famous caricature of Louis Philippe, which appeared in 1834 in the Paris magazine Charivari and defamed the French king by turning his head into a mushy pear.

Les Poires (The pears). Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), 1834.

Les Poires (The pears). Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), 1834.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 6 August 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Another caricature from Punch also presents human-plant hybrids. The unnamed artist imagines a Grand Show of Prize Vegetarians, alluding to colonial ethnological expositions. Each of the hybrid figures presented and even offered for sale amazes its audience with individual physical features. Their different appearances are the results of their respective diets. The carrot woman, for example, as a sign next to her explains, was raised exclusively on carrots. The cartoon shows to what extent vegetarians were publically perceived as a separate, “foreign people.” It is up to the beholder, however, to decide whether the artist mocks the vegetarians for the public display of their lifestyle or criticizes the amazed audience for their voyeurism.

Grand Show of Prize Vegetarians. Unknown artist, 1852.

Grand Show of Prize Vegetarians. Unknown artist, 1852.

Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.

Originally published in Punch’s Almanack, 1852.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

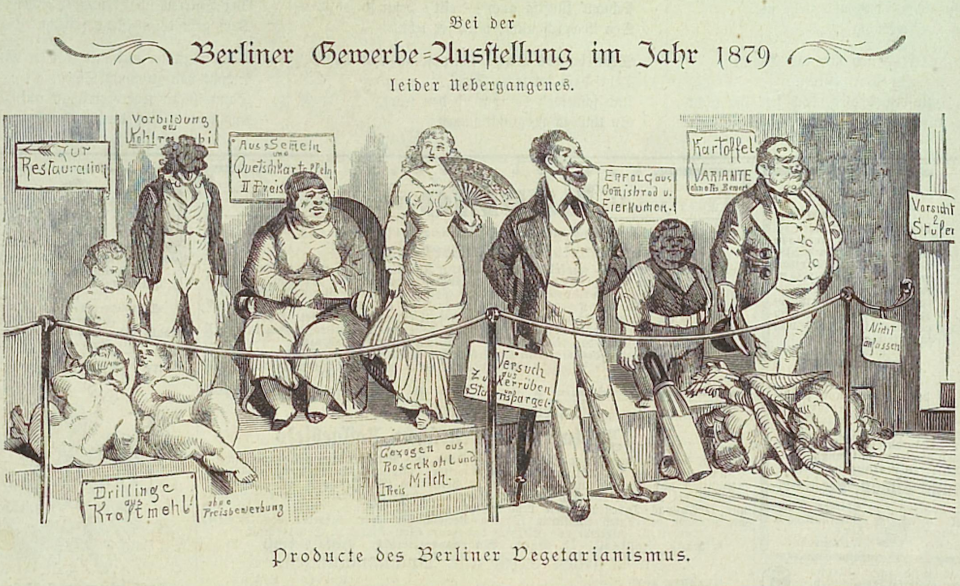

One of the earlierst vegetarian caricatures from a German satirical magazine that demonstrates that vegetarianism had by then arrived in Germany, also picks up on this idea and exposes similarly hybrid Producte des Berliner Vegetarianismus (“Products of Berlin Vegetarianism”) at the Berlin trade exhibition in 1879. This caricature, however, modifies the joke of its English predecessor; unlike in London, where the human vegetables received much attention, they were “unfortunately ignored” in Berlin, as the small printed subtitle makes clear. It may allude to the fact that in 1879 Berlin was not yet quite ready for this life reform movement.

Producte des Berliner Vegetarianismus (Products of Berlin Vegetarianism). Wilhelm Scholz (1824–1893), 1879. “Bei der Berliner Gewerbe-Ausstellung im Jahr 1879 – leider Übergangenes.” (“At the Commercial Exhibition 1879 in Berlin—unfortunately ignored”).

Producte des Berliner Vegetarianismus (Products of Berlin Vegetarianism). Wilhelm Scholz (1824–1893), 1879. “Bei der Berliner Gewerbe-Ausstellung im Jahr 1879 – leider Übergangenes.” (“At the Commercial Exhibition 1879 in Berlin—unfortunately ignored”).

Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.

Originally published in Kladderadatsch: Humoristisch-satirisches Wochenblatt 32 (1879): 455.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

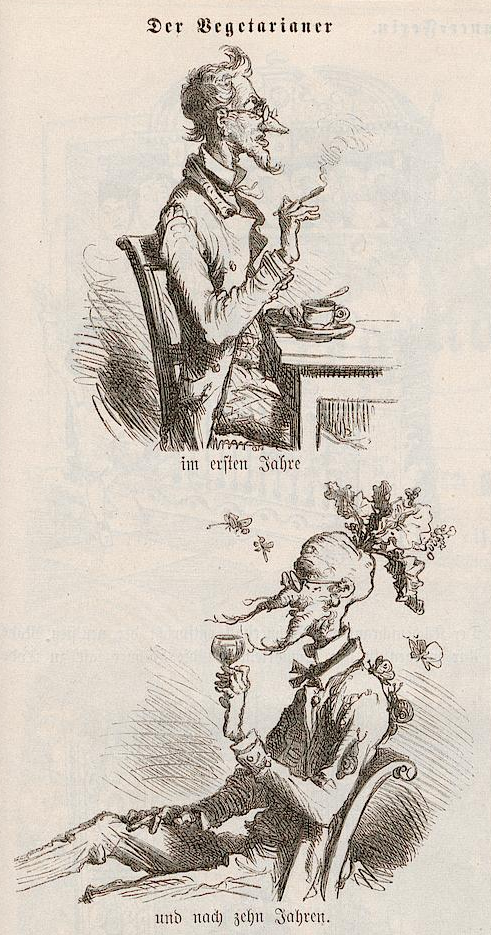

The early idea that a vegetarian might gradually transform into a plant is visualized in a particularly detailed cartoon of the same year.

Der Vegetarianer (The vegetarian). Edmund Harburger (1846–1906), 1879.

Der Vegetarianer (The vegetarian). Edmund Harburger (1846–1906), 1879.

Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. Originally published in Fliegende Blätter 70, no. 1745–1770 (1879): 135.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Der Vegetarianer

im ersten Jahre und nach zehn Jahren.The vegetarian

in his first year and after ten years.

This very common notion of a correlation between (peaceful, fragile) physical appearance and (meatless) nutrition as well as vice versa, a burly physique and meat consumption—is called into question by an 1869 cartoon from Punch. Its title A Gentle Vegetarian is ironically attributed to the herbivorous, but weighty and threatening hippopotamus. Its counterpart is the elegant lady, whose human physique does not betray that this species for the most part consists of carnivores.

A Gentle Vegetarian. George du Maurier (1834–1896), 1869. “Morning, Miss! Who’d ever think, looking at us two, that you devoured Bullocks and Sheep, and I never took anything but Rice?”

A Gentle Vegetarian. George du Maurier (1834–1896), 1869. “Morning, Miss! Who’d ever think, looking at us two, that you devoured Bullocks and Sheep, and I never took anything but Rice?”

Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.

Originally published in Punch 56 (1869): 90.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The idea that a person’s diet is reflected not only in their appearance, but also in their character, was widespread in the nineteenth century—among the vegetarians as well as their mockers. While one side argued one was brutalized by meat consumption, the other argued one was made effeminate by abstinence from meat. Rousseau, whose famous educational treatise titled Émile strongly influenced nineteenth-century vegetarianism, warned his readers not to change the “natural taste” of children, who preferred vegetable food, so as not to make them “flesh-eaters”: “if not for their health’s sake, for the sake of their character. For … it is certain that great meat-eaters are usually more cruel and ferocious than other men” (1762, 513). “Wild” peoples, whose cruelty stemmed solely from their meaty diet, were cited as evidence; Rousseau even references Homer’s Odyssey and contrasts the carnivorous Cyclops as a “terrible man” to the Lotus-eaters, who were “so delightful” that their visitors wanted to live among them forever (1762, 513).

Additionally, the Germans’ ideals must be seen against the background of the struggle for state formation in the nineteenth century. Vegetarians and their opponents each claimed that only their diet would incite in people the unconditional will for freedom and the needed fighting spirit. While the opponents said that the vegetable diet led to a weak character and the inability to fight, Eduard Baltzer, founder of the first vegetarian society, argued that meat consumption endangers not only “conscience” but also freedom, as he puts it in the poem Thalysia printed on the front page of the first issue of his magazine on vegetarianism, the Vereins-Blatt für Freunde der natürlichen Lebensweise (Vegetarianer). Here he imagines a vegetarian utopia:

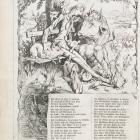

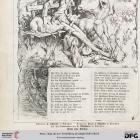

Thalysia.

Frontpage of the first edition of the Vereins-Blatt für Freunde der natürlichen Lebensweise (Paper for friends of the natural way of life), 1868.

Frontpage of the first edition of the Vereins-Blatt für Freunde der natürlichen Lebensweise (Paper for friends of the natural way of life), 1868.

© Gießen, Universitätsbibliothek, FH Eden Z.

Vereins-Blatt für Freunde der natürlichen Lebensweise (Vegetarianer) 1 (1 June 1868): 1.Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Die Welt liebt Blut, und wieder Blut;

…

Und Thier und Mensch wird’s Opfergut,

…Die Welt liebt Jagd, die heisse Jagd

nach Geld und Ruhm und nach “Genüssen”.

So sinkt sie hin, des Lasters Magd,

Sie jagt sich todt und ihr Gewissen:

Wer wird im Lande gier’ger Sarkophagen

Noch nach der Freiheit ächtem Liede fragen?Komm Ceres, in die arme Welt,

Komm wieder, ihre Schuld zu mildern.

Bau Du Dein Haus, ein rein Gezelt,

Ein Musenreich den Menschenkindern …Thalysia.

The world loves blood, and more blood;

…

And animal and man become the offering,

…The world loves hunting, loves the chase

Of money, fame and “pleasures.”

So will the Vice’s maid collapse,

Hunting herself to death and her conscience:

Who will, in the land of greedy sarcophagi [“meat-eaters”],

Still ask for the true song of freedom?Come, Ceres, hear the world’s lament,

Come back to ease its burden;

Build your house, a simple tent,

A kingdom of muses for human children …—Eduard Baltzer, “Thalysia,” in Vereins-Blatt für Freunde der natürlichen Lebensweise (Vegetarianer) 1 (1 June 1868): 1.

(Trans. Kimberly Coulter.)

However, for most vegetarians, other, more personal reasons were crucial for joining the society. Eighty to ninety percent of the members were hoping vegetarianism might cure them from a disease (Teuteberg 1994, 58). There was much debate over whether a meat-rich or a meat-free diet was better for human health. From the middle of the nineteenth century, scientists such as Justus von Liebig promoted animal protein—especially in the form of meat—as indispensable for health and labor. At the same time, healing practitioners such as Theodor Hahn prescribed abstinence from meat as a central remedy. Judged from today’s perspective, the tone and the arguments of these debates were often quite unscientific and distorted by the fact that being “vegetarian” often meant not only abstaining from meat, but also from alcohol, tobacco, spices, caffeine, and other stimulants.

The vegetarians rebutted the prejudice of being physically inferior to meat-eaters by their successful participation in long-distance marches. This is also picked up by a caricature which appeared in 1893 after the long-distance march from Berlin to Vienna, in which two vegetarians reached the destination and finish line first. While the “Reception of Vegetarians” is mocked as mere publicity for vegetable sellers, the winners—despite their success—are portrayed as haggard and weakened, matching the cliché. However, such events were in fact remarkable promotional successes for the vegetarianism movement itself (see Bollmann 2017, 137–38, and Pack 2018).

Der Empfang der “Vegetarianer” vom Distanzmarsch (The welcoming of the “vegetarians” after the long-distance march). Unknown artist, 1893.

Der Empfang der “Vegetarianer” vom Distanzmarsch (The welcoming of the “vegetarians” after the long-distance march). Unknown artist, 1893.

Courtesy of ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. All rights reserved. Petition for orphan work status pending.

Originally published in Kikeriki, 11. June 1893: 2.

Click here to view source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Der Empfang der “Vegetarianer” vom Distanzmarsch

hätte am Naschmarkt stattfinden sollen, denn eine solche Kohlrabi-Reklame ist noch nicht dagewesen!The welcoming of the “vegetarians” after the long-distance march

should have taken place at the Naschmarkt [i.e. Vienna’s biggest market], because never before has there been such promotion for cabbage turnip!