Werksviertel-Mitte

A showcase for nature in the Ostbahnhof neighborhood?

A rooftop in the Werksviertel.

A rooftop in the Werksviertel.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In the Werksviertel the urban future of Munich is being reinvented. The development of the former industrial district is based on a social vision: inclusion and bringing together diverse elements. The site—once home to the potato factory Pfanni—hosts experimental projects alongside tried-and-true, a youth hostel beside a hotel, people in the pub and sheep on the roof. It is planned with a view to people and city. But equally clear is the desire for nature. One of the stairways houses an ant colony in a glass pipe, graffiti animals romp about on dumpsters and walls. Is it also possible to find “pristine” nature here? How fresh is the air of the neighborhood? Where can we find traces of the Munich loam deposit? And what is a potato washing road? The Werksviertel has a rich history, and the plans for the future are ambitious. Is it possible to find a successful balance between past and future, between city and nature?

The Werksviertel-Mitte has many green areas. One example are these mobile plots, which are used to plant herbs and fruit.

The Werksviertel-Mitte has many green areas. One example are these mobile plots, which are used to plant herbs and fruit.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Apart from a few trees, more than 90% of the grounds in the Werksviertel-Mitte are sealed. In fact, Munich is the city in Germany that has the most sealed areas. In total, about 47% of the city area is sealed. The Werksviertel is no exception.

Apart from a few trees, more than 90% of the grounds in the Werksviertel-Mitte are sealed. In fact, Munich is the city in Germany that has the most sealed areas. In total, about 47% of the city area is sealed. The Werksviertel is no exception.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Chimneys, pipes, and old train tracks

In the past, this street transported and washed potatoes, that were then processed into dumplings and purée. Today, grids cover the street.

In the past, this street transported and washed potatoes, that were then processed into dumplings and purée. Today, grids cover the street.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

A collection of odd objects tell the history of a village and a potato empire. Today a district of Munich, the first recorded mention of Berg am Laim is from 812, where it is referred to as the hill (Berg) along the clay field (Lehm). It was not incorporated into Munich until 1913, when the growing city was in urgent need of space. Industries emerged. The largest industry to occupy the district after the Second World War was Pfanni, a dumpling and mashed-potato production factory. Each year, 1,200 workers processed up to three million centners of potatoes from the Munich region. To enable the tubers to be stored for long periods, the water was extracted from them—a global innovation. After food manufacturing within the city ceased and was transferred elsewhere in 1993, the Pfanni factory closed its doors in 1996. It was replaced by cultural centers—the Kunstpark Ost and Kultfabrik. Urban gardens, compost heaps and raised beds—showcases of nature—have replaced industrial food production. A journey of discovery through this district still reveals remnants of the old potato washing facility. Tracks, canals, and pipes reveal the manufacturing activities of the past.

The laws of nature are being turned upside down in the Werkviertel

Here, sheep live on the rooftop, whales on the walls, and ants in pipes. On the roof of WERK3, there is an alpine pasture school. School classes come here, so students can learn conscious interactions with the environment.

Alpine pasture life on a rooftop in the Werksviertel

Valais blacknose sheep live on a rooftop in the Werksviertel.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Miniature alpine pasture: Chicken, bees, a hut, and Valais blacknose sheep reside on top of the 2500 square meter rooftop of WERK3.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Chicken are also residents on the rooftop of WERK3.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Chickens are also part of the rooftop alpine pasture.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

More than one-third of the Bavarian bees are residing in urban areas. In Munich, in addition to the honeybee, there are 192 different species of wild bees. In the Werksviertel, most bees are primarily the alpine pasture school’s honeybees.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Honeybees on the rooftop of WERK3 in the Werksviertel.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

In the Werksviertel, you can see real honeybees, but you can also encounter artistic depictions of them on the walls of the Werksviertel, like this mural that was created by Loomit.

Photograph by Helena Held. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by Loomit.

However, the sheep and chicken are not the first encounters with animals when one visits the Werksviertel. Colorful graffiti of animals can be found on walls and on containers; they create the impression of a world rich in wildlife. Is this displayed nature the only one that can be found here? Which animals do come here, apart from ants, nocturnals rats and foxes?

Animals and art in the Werksviertel

The artist Loomit has created a depiction of the ants in a staircase.

Photograph by Helena Held. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by Loomit.

Giant leafcutter ants, originally from South America, are living in the Werksviertel, too.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Giant leafcutter ants, originally from South America, are living in the Werksviertel, too. Here they are climbing up a pipe that leads to the alpine pasture school on the rooftop. These ants are better suited for this habitat because they travel further than native ants.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

The artist Mr. Woodland has created this artwork of a bird in a tree.

Photograph by Helena Held. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by Mr. Woodland.

A fox can also be sighted on the grounds of the Werksviertel. This artwork was created by Loomit.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by Loomit.

Snakes can also be found—on the walls of the Werksviertel, created by ATE.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by ATE.

Loomit created this depiction of a tapir family.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by Loomit.

The artist Loomit created this artwork of a whale on the side of a building in the Werksviertel.

Photograph by Helena Held. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Graffiti by Loomit.

Throughout the Werksviertel, several different animals are depicted by several artists. This map shows where to find them.

Graphic design by Helena Held and Talitta Reitz. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Google Maps was used as a reference. All icons have a CC BY license by the Noun Project: The bee was created by Syaiful Amri; the sheep by Alena Artemova; the ant by parkjisun; the cat by REVA; L Marco Livolsi; the fish by Baboon designs; the whale by Felix Brönnimann; the chicken by Yugudesign; the hippo by Ed Harrison; the bat by Tatyana; the rat by designer468; the monkey by TkBt; the rabbit by Marina Sas TkBt; the snake by Bakunetsu Kaito; the elephant by Kris Prepiakova; and the tapir by Laura Barretta. All artists have contributed to the Noun Project.

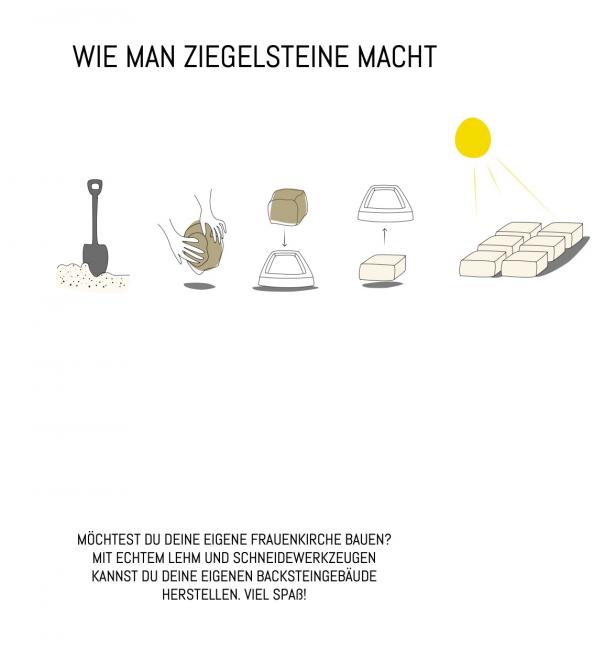

Stone by stone, Berg am Laim became a part of Munich’s history

The suburb is located where a “tongue of clay,” an elongated clay deposit, once existed. Princes used this excellent building material for their buildings. The factories in Munich-East delivered bricks, which added to the rapid growth of the city. The technological advancements also multiplied the brick factories. Landowners enriched themselves and began to hire Italian seasonal workers for the strenuous work. The beautiful bricks within Munich’s walls are visible to this day. The factors, however, were they were created do not exist anymore. Exploiting the geological clay deposit for centuries resulted in its complete disappearance. Only the name of the suburb, Berg am Laim, refers back to the past of a “hill of clay.”

The role of clay in Munich’s history

About 20,000 years ago, meltwater flowed from the glaciated Alps to the north. On a terrace, loess and dust deposited a geological layer of clay: This created Munich’s “tongue of clay.”

Drawing by Talitta Reitz. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Past and future in the Werksviertel-Mitte: The new WERK17 has a brick façade, which reflects the history of clay in the Berg am Laim suburb.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Past and future in the Werksviertel-Mitte: The new WERK17 has a brick façade, which reflects the history of clay in the Berg am Laim suburb.

Photograph by Laura Kuen. CC BY 4.0 international license.

Numerous brick buildings have shaped the city of Munich. But only few people in Munich know where the bricks have come from.

Photograph by Wikipedia / Tobias Klenze. It can be found here.

The Werksviertel-Mitte station during the Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition.

The Werksviertel-Mitte station during the Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

About the curators

Helena Held

Helena Held studies visual anthropology and is always interested in the interface between anthropology and art. Therefore she presented her outcome of the research of her bachelor thesis in an exhibition. She made a film together with some fellow students about the wool production on the Shetland Islands and presented a short film at the Venice Bienniale. She studied at the Venice International University (VIU) and the University of Oslo (UiO), where she visited transdisciplinary courses and worked on environmental topics like food studies and ecofeminism.

To me it is really interesting how such a small and constantly changing suburb as the Werksviertel can combine art, culture, and nature in such creative ways. At the same time, we should not loose sight of the fact that the city is also an important habitat for non-human beings.

—Helena Held

Vera Klünder

Vera Klünder studies public health.

I find it particularly fascinating how large the influence is that greenways and fresh air have onto the urban climate. In a time that is impacted by climate change, measurements of climate regulations such as these are essential.

—Vera Klünder

Talitta Reitz

Talitta Reitz is a graduate landscape architect and urbanist, and a certified heritage conservationist from University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Originally from Brazil, she has a background in architecture and urbanism from Federal University of Parana, Curitiba, where she worked for architecture offices and local and federal institutions for heritage conservation. In 2016, she was the recipient of the ASLA “Student Design Merit Award,” and of the Tau Sigma Delta Honor Society in Architecture and Allied Arts “Design Excellence” Medal. Currently, she is an early stage researcher of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie RECOMS Innovative Training Network and a PhD candidate of environmental humanities at the Rachel Carson Center at LMU Munich.

Cities are not just layers on top of the natural environment, but they are influenced by landscapes, societies, and the collective memory. All of it forms an interconnected network that is constantly changing.

—Talitta Reitz

How to cite: Held, Helena, Vera Klünder, and Talitta Reitz. “Werksviertel-Mitte.” In “Ecopolis München 2019,” edited by Katrin Kleemann. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2020, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/9021.