Munich Airport

Economy instead of ecology?

Every year, 46 million airline passengers pass through Munich. The airport provides the region with tremendous flexibility, a respectable income, and goods from around the world.

Roughly every 50 seconds an airplane takes off or lands at Munich Airport.

Roughly every 50 seconds an airplane takes off or lands at Munich Airport.

Photograph by Johanna Felber.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

But flying is bad for the environment: the noise disturbs those who live in nearby communities, and the emissions of greenhouse gases aggravate global warming. In response, the airport has undertaken a number of measures in order to become carbon neutral—at least on the ground.

It is too late, however, to rescue the Erding peat deposits, which were cleared for the construction of the buildings and tarmac. Although parts of the bog had already been drained, the airport brought about immense changes to the landscape.

The original Erding peat bog (green color) and the airport with the proposed third runway.

The original Erding peat bog (green color) and the airport with the proposed third runway.

Graphic design by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng.

Used with permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The world’s peat bogs are valuable, but endangered habitats for countless animal and plant species. Most bog landscapes have been destroyed after being drained for human use.

The Munich airport wants to be green. But it used to be much greener here. How high is the price for humans and nature?

The biography of a bog

Once the Erding peat bog covered an area of 25 km2 situated west of the Isar, between Riem and Moosburg. It was created by the pooling of groundwater that seeped to the surface at the edge of the Munich gravel plain.

Early settlers occasionally used the bogland for grazing their animals. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century peat was harvested from it. More and more areas of the bog were drained in order to use the land for agriculture and the peat for fuel.

When construction of the airport began in 1980, the water level had already receded significantly.

Even at this early stage, there were strong protests from the population. Three runways were planned, but only two have been constructed. Today the third runway is once again a matter of dispute. How severe is in fact the environmental impact of the airport?

The Munich Airport station in the physical Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition.

The Munich Airport station in the physical Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

No peat bog without water

A small branch of the river Moosach in the Freising peat bog has been renaturated.

A small branch of the river Moosach in the Freising peat bog has been renaturated.

Photograph by Johanna Felber.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The largest part, however, still is a canal.

The largest part, however, still is a canal.

Photograph by Johanna Felber.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Dry soil is a matter of security for the airport. Rescue vehicles must be able to drive across the fields in case of an emergency. The soil near the runways has therefore been drained particularly carefully.

Draining the bogs has started even in the early modern period. Starting from 1850, more and more canals were built to redirect the water. In the early twentieth century, the Erding peat bog has been drained almost completely. Many plants, which had adjusted to the conditions in the bog, could no longer survive.

By the early twentieth century, the former peat bog dried out so much that dust storms formed. Once pastures and forests had been created, the situation improved again.

Common sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) can be found in bogs in the northern hemisphere. Its existence is, however, endangered because bogs are being drained and peat is being extracted.

Common sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) can be found in bogs in the northern hemisphere. Its existence is, however, endangered because bogs are being drained and peat is being extracted.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Inhale—exhale

An Airbus A320 airplane takes off from Munich Airport.

An Airbus A320 airplane takes off from Munich Airport.

Photograph by Johanna Felber.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In 2017, the airport used around 510,000 megawatt-hours of energy and emitted around 150,000 tons of carbon dioxide. This would fuel an Airbus A320 airplane, fully occupied with 180 passengers, to fly around the Earth approximately 100 times.

The airport aims to become climate neutral by 2030. To achieve this goal, the annual emission has to be reduced by 60% and the rest has to be compensated for. This calculation does not include the fact that not only the airport emits carbon dioxide, but the airplane flights themselves also emit additional carbon dioxide.

This looked different in the past. Plants take in carbon dioxide and deposit it as peat in the bog; this created a large carbon dioxide storage. Roughly one-fifth of the entire carbon dioxide worldwide is stored in peat bogs. One hectare of fens, such as the Erding peat bog, can take in more than 30 tons of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases per year. While the area used to “inhale” carbon dioxide, the area now “exhales” it again into the atmosphere and therefore affects the climate.

A model showing the different layers of peat deposits. When plants die, they deposit in the bog and become peat. When the peat is being extracted and burnt, the stored carbon dioxide is released to the atmosphere again.

A model showing the different layers of peat deposits. When plants die, they deposit in the bog and become peat. When the peat is being extracted and burnt, the stored carbon dioxide is released to the atmosphere again.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Bird protection or damage control?

A lapwing (Vanellus vanellus).

A lapwing (Vanellus vanellus).

Photograph by Augustín Povedano.

It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

In 2008, around 4.5 km2 of the Erding peat bog have become a bird reservoir. This includes the fields on the grounds of the airport.

The fences of the airport protect ground-nesting birds, such as the endangered lapwing from dogs and tractors. Nevertheless, the area is not ideal: The lapwing needs wet meadows. Most mates are breeding in the northern fields of the airport, as the groundwater is higher here. In 2015, around 200 lapwing mates were breeding in the fields around the airport.

A lapwing’s eggs. Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) exist in Eurasia, but they are endangered because there are only few breeding sites due to intensive agriculture and densely populated areas.

A lapwing’s eggs. Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) exist in Eurasia, but they are endangered because there are only few breeding sites due to intensive agriculture and densely populated areas.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The third runway is planned to be built to the north of the existing airport. This way, surrounding fields would also become part of the bird reservoir. However, do we need a new runway to protect the lapwing?

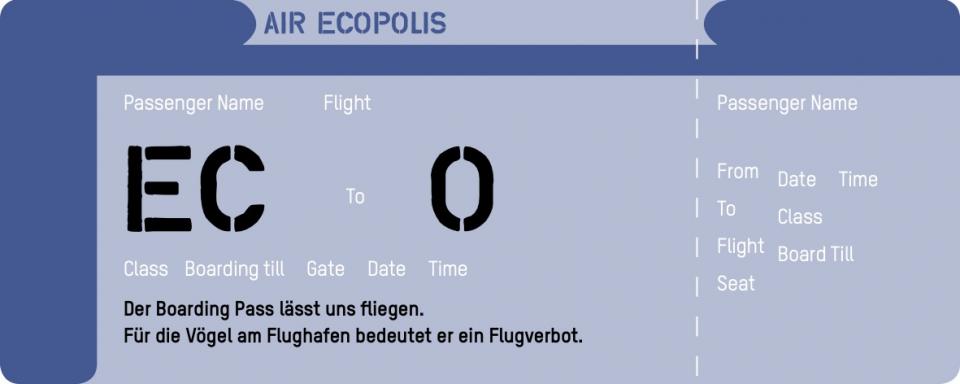

This boarding pass allows humans to fly. For the birds on the airport grounds, it, however, signifies a flying ban.

This boarding pass allows humans to fly. For the birds on the airport grounds, it, however, signifies a flying ban.

Graphic design by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng.

Used with permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In order to get a sense of what the Erding peat bog and the Munich airport sound like, you can listen to this audio.

This content is an audio file mixed by Xiao Wang. It includes the sound of various animals, birds, and insects, as well as the sounds of airplanes starting and landing at Munich Airport.

This audio file was mixed and edited by Xiao Wang using Audition. The audio file consists of audio recordings by Xiao Wang taken at the Erding peat bog and at Munich airport, which are licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Furthermore, the audio file also includes recordings hosted by the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. These audio recordings are of the Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata) (ML Audio 230914); a boar grunt (Haemulon plumierii) (ML Audio 112436); an European Roe (Capreolus capreolus) (ML Audio 36230); a horse (Equus caballus) (ML Audio 219820); and the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) (ML Audio 231205). Used with permission.

Additionally, the audio file also includes compositions from the website naturesoundsfor.me. Specifically, the following compositions were used: The composition “Forest Ambience”, which uses sound created by Benboncan, from “Woodpeckers Pecking 2.wav”; by dobroide, from “20080528.forest.wind.soft.birds.flac”; by Erdie, from “bee-colony.flac”; by inchadney, from “Frogs.WAV.” The composition “Forest Birds”, which uses sound created by Benboncan, from “Tawny Owls 2.wav”; by imonacan, from “whippoorwill3.wav”; by jm__, from “NorthwesternStateFountain.mp3”; by reinsamba, from “Nightingale song 3.wav.” The composition “Fountain”, which uses sound created by jm__, from “NorthwesternStateFountain.mp3.” These sounds are licensed under CC BY licenses.

About the curators

Johanna Felber

Johanna Felber is about to finish her master’s degree in communication and environmental studies. Throughout her studies, she has focused on discourses and how they shape society. To her, the Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition signifies a perfect combination of her studies: Telling a different story about a city, compared to what we already thought we knew.

At first, the topic airport seemed clean-cut to me: not very environmentally friendly. However, once we really looked into the topic, it became clear that the airport was a large but final step in the story of how the peat bog developed—for now.

—Johanna Felber

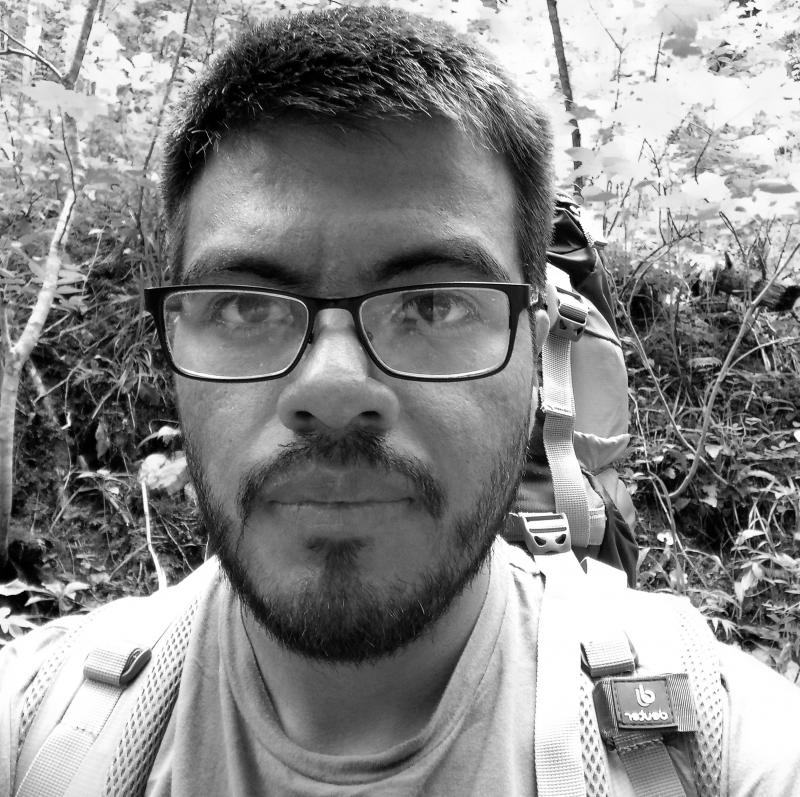

Hugo Reyes Aldana

Hugo Reyes Aldana holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). After that, he decided to come to Germany in order to obtain a master’s degree in evolution, ecology, and systematics from LMU Munich, where he also joined the Environmental Studies Certificate Program of the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. Hugo is currently a PhD candidate at the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research in Magdeburg, where he studies the multiple interacting factors that influence ecosystem metabolism and how this can be used for monitoring and restoring aquatic environments.

I always thought of cities as the opposite of nature. Perhaps Munich might be an exception to this rule. The history of the airport has changed my mind in this regard: Many different interests were prized above the uniqueness of the ecosystem. Where is the ‘Eco’ in ‘Ecopolis’?

—Hugo Reyes Aldana

Xiao Wang

Xiao Wang studied linguistics and environmental studies at LMU Munich. She was born and raised in China, and she is now living in Germany. Xiao is interested in the impacts of different societal patterns on environmental problems

In the beginning, I was admiring how much the airport tried to implement environmentally friendly strategies. However, when I looked into the topic more closely and even visited the peat bog I came to realize that only very little is left of the actual bog, which left me with a gloomy feeling: Does nature always have to be sacrifized for economic development?

—Xiao Wang

How to cite: Felber, Johanna, Hugo Reyes Aldana, and Xiao Wang. “Munich Airport.” In “Ecopolis München 2019,” edited by Katrin Kleemann. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2020, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/9023.