Ismaning Reservoir

A wastewater lake changes its feathers?

At the Ismaning Reservoir approximately an hour by bike northeast of Marienplatz the interplay between humans and nature is evident. It is not possible to swim in the lake. But it does more than just store water for Munich power generation facilities. It also provides habitat for many species.

There is no boat rental, no beach, no kiosks or tourism. Built in 1929, the reservoir and the canal connecting it to the Isar River help to regulate the water flow to the nearby hydroelectric plants and for cooling the turbines of the thermal power station Heizkraftwerk Nord. The 95 adjoining ponds of the fish farm Birkenhof purify the city’s wastewater through natural means.

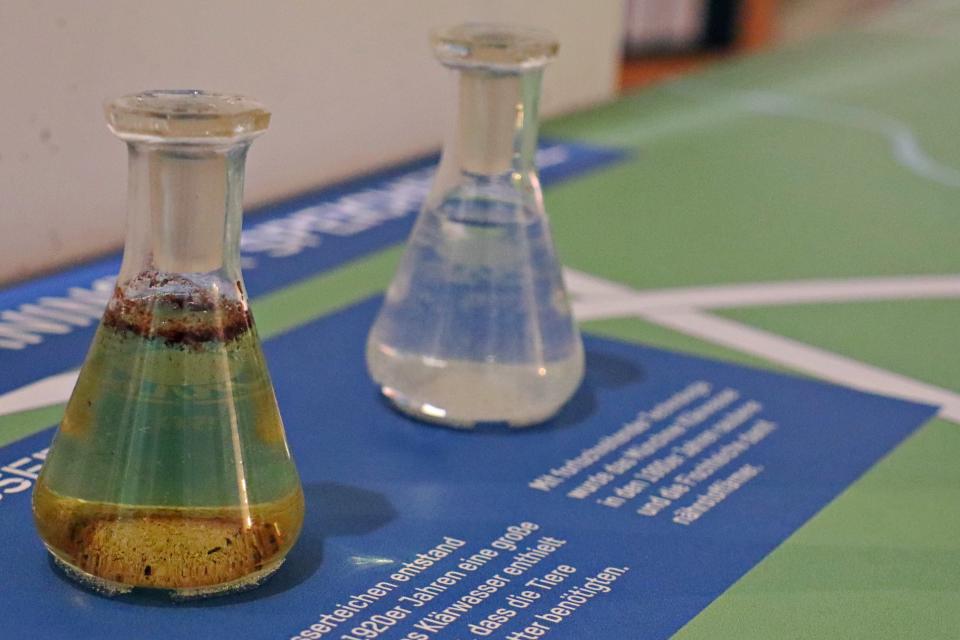

Left glass: Large-scale carp breeding started in the wastewater lakes in the 1920s. The wastewater contained so many nutrients that the animals did not need any additional feed.

Right glass: With advancements in technology, Munich’s wastewater became cleaner in the 1990s. As a consequence, however, the water contained fewer nutrients.

Left glass: Large-scale carp breeding started in the wastewater lakes in the 1920s. The wastewater contained so many nutrients that the animals did not need any additional feed.

Right glass: With advancements in technology, Munich’s wastewater became cleaner in the 1990s. As a consequence, however, the water contained fewer nutrients.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

What fascinates me about the Reservoir is the multitude of different aspects that are coming together: For instance the progressive energy project, the wastewater treatment, the decades-long pond farming, the large bird reservoir, and the positive influence on the groundwater and the climate.

—Rudolf Lukes, local resident

Technological progress has altered the ecosystem of the lake and the ponds and unintentionally created the largest moulting grounds for water birds in central Europe. But is it possible for the wastewater in the ponds to be too clean? And why is the thermal power station good for the rare mercury bluet?

Although the reservoir is almost the same size as the Tegernsee, which is a popular tourist destination, most people from Munich have never heard about the Ismaning Reservoir.

Although the reservoir is almost the same size as the Tegernsee, which is a popular tourist destination, most people from Munich have never heard about the Ismaning Reservoir.

Graphic design by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng.

Used with permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The dream of electricity from the Isar

The construction of the reservoir was part of a grand vision: the electrification of all of Bavaria. Prior to the construction of the first hydroelectric plants in 1896, only mill wheels were used to produce energy. For the first time, the Ismaning Reservoir and its respective power plants were supposed to supply energy to half a million households in Munich.

A grand vision: the electrification of all of Bavaria

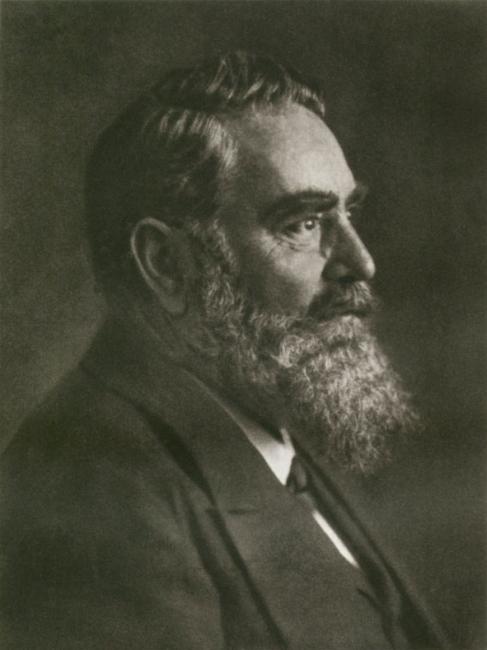

Oskar von Miller, the founder of the Deutsches Museum and a visionary of hydroelectric power, initiated the construction of the Ismaning Reservoir.

This image is in the public domain. It can be found here.

Wildlife

The Unterföhrung thermal power station cools its turbines with the water from the Isar canal. Afterward, the heated water reaches the Ismaning Reservoir. This contributes to the fact that the lake does not freeze over—not even during the deepest winter. One species particularly appreciates this: The mercury bluet (Coenagrion mercuriale), which is a protected dragonfly species, finds ideal living conditions because of the existence of the thermal power station.

A mercury bluet (Coenagrion mercuriale).

A mercury bluet (Coenagrion mercuriale).

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In order to create the reservoir a large area of peat bog was drained. Today such a major alteration of the landscape would be met with immense resistance. In addition to the marshland, many villages were destroyed by the project of creating the artificial lake.

My father was a fisherman at the fish ponds. The working conditions were extremely difficult, particularly during the wintertime when the fishing began before Christmas.

—Gerda Lukes, local resident

Many people lost their land as a result of the construction of the reservoir.

Many people lost their land as a result of the construction of the reservoir.

Photograph by Gerda Lukes. Photograph supplied by Malin Klinski.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

For others, the power station and the fish farming meant hard work, but also new livelihoods.

For others, the power station and the fish farming meant hard work, but also new livelihoods.

Photograph by Gerda Lukes. Photograph supplied by Malin Klinski.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Where does the water in the reservoir come from? In Oberföhring 150 m3 of water per second is diverted from the Isar through the Mittlerer Isarkanal. As a result of the reduced water level in the Isar, many fish species that once lived in the river have now vanished.

The dream of energy drove the fish out of the Isar; however, the creation of the reservoir also inadvertently created a new habitat for countless birds. In July 2015, a counting showed that 60,000 birds were present at the Ismaning Reservoir.

The Ismaning Reservoir serves as a habitat for many different birds

The eastern part of the reservoir (Ostbecken) at twilight.

Photograph by Erwin Taschner. Used with permission.

Today the reservoir is a habitat for countless birds, such as coot.

Photograph by Erwin Taschner. Used with permission.

Today the reservoir is a habitat for countless birds, such as great chested grebe.

Photograph by Erwin Taschner. Used with permission.

Today the reservoir is a habitat for countless birds, such as red-crested pochard. Once per year, these birds change their entire feathering at the reservoir.

Photograph by Karin Haas. Used with permission.

It is simply fantastic when the summer comes and ducks start to fly in from all around Europe. Out of all places, they come here to cast their feathers. It was an absolutely unintended consequence that an artificial reservoir became a unique port of call for feral water birds from all over Europe. This place should be protected permanently.

—Karin Haas, ornithologist at the Landesbund für Vogelschutz e.V (LBV), an environmental organization that protects birds

The Ismaning Reservoir is home to many different species.

The Ismaning Reservoir is home to many different species.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

About the curators

Malin Klinski

Malin Klinski received her bachelor’s degree in cultural anthropology, with a minor in communication studies, from LMU Munich in 2018. Her interest in environmental studies developed while participating in a seminar on human-environment relations in connection to natural disasters during her exchange semester at the Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She is currently pursuing her master’s degree in intercultural communication at LMU. Being born in Munich, she has never stopped being enthusiastic about exploring unknown aspects of the environment of her hometown.

Anne Schilling

Anne Schilling became part of the Ecopolis München 2019 team when she was still quite new in Munich. It was a wonderful chance for her to get to know the city as a whole, detecting different interrelated stories and challenges. Anne joined the Environmental Studies Certificate Program because she was always interested in green spaces and nature per se. Now she had the chance to learn about and discuss highly relevant topics regarding the environment and society in a very interdisciplinary and enriching academic environment.

The artificially created lake seemed like a green oasis to us. Flowers were in bloom at the shores and water birds covered the ponds like carpets. The birds were not really interested in the ponds without the wastewater. Thanks to Karin Haas we were even able to see the areas of the reservoir where access is usually restricted.

—Malin Klinski and Anne Schilling

How to cite: Klinski, Malin, and Anne Schilling. “Ismaning Reservoir.” In “Ecopolis München 2019,” edited by Katrin Kleemann. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2020, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/9020.