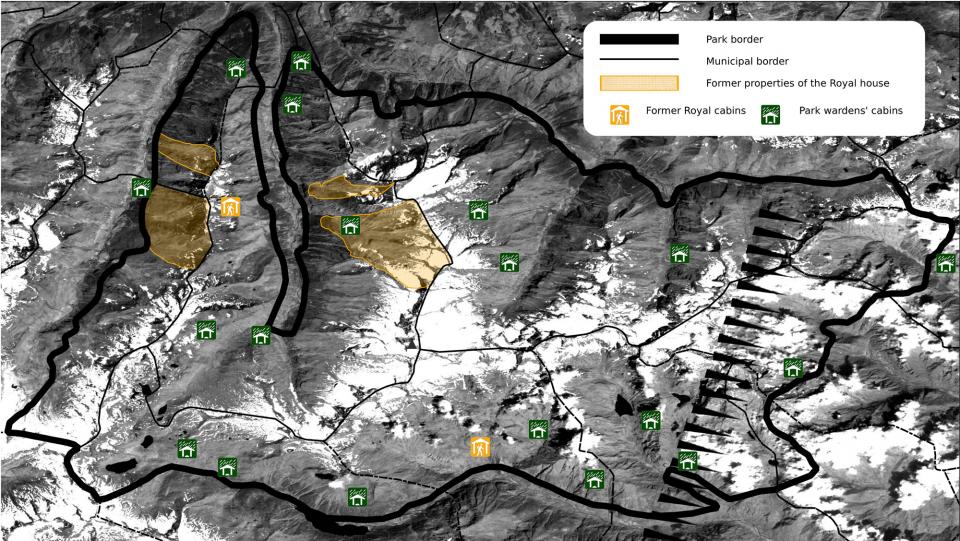

The Gran Paradiso area has historically been at the core of attempts made by the Piedmontese royal house to preserve the ibex (Capra ibex). By 1821 the Piedmontese government had forbidden ibex hunting. Nonetheless, poaching continued almost unabated on the Gran Paradiso massif, where between 1850 and 1856 King Vittorio Emanuele II established a royal hunting reserve, based on a complex system of tenancies with private landowners. This act saved the Alpine ibex from extinction and the ibex populations in the Alps today stem from this original stock.

Ibex in the Gran Paradiso National Park (1933)

Ibex in the Gran Paradiso National Park (1933)

1933 Photo by Ugo Beyer for “Le Vie d’Italia” of the Touring Club Italiano

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

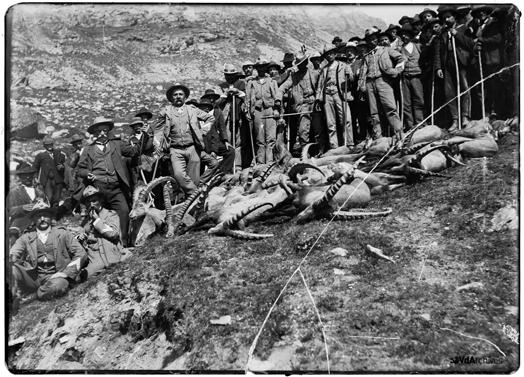

In September 1919 King Vittorio Emanuele III offered to donate the hunting reserve to the Italian state. However, its inauguration as the first Italian national park was delayed until the end of 1922, when the new Fascist regime decided, as an act of propaganda, to support the project. In the interim, the former hunting reserve became something of a no-man’s-land and a veritable paradise for poachers. Ibex and chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) hunters, dressed in military outfit and armed with machine guns, were a common sight before 1922.

A scene from the royal hunts in the Gran Paradiso area, early 20th century

A scene from the royal hunts in the Gran Paradiso area, early 20th century

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Fondo Brocherel-Broggi – Regione Autonoma Valle d’Aosta

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Thereafter, conflicts with local communities entitled to hunting rights outside the King’s former private properties arose. These rights were dismissed without provisions being made for compensation. Further conflicts arose between those planning a park for the promotion of mountain tourism in accordance with the so-called American model of recreational parks and those in support of an “ibex sanctuary,” a park purely intended for the purposes of conservation and scientific research in accordance with the Swiss model. The Gran Paradiso National Park was ultimately a compromise in which tourism and conservation could coexist.

Map of the Gran Paradiso National Park

Map of the Gran Paradiso National Park

2011 Wilko Graf von Hardenberg

Raster image by Sando Furieri/USGS Landsat imagery

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

How to cite

Hardenberg, Wilko Graf von. “From Royal Hunting Reserve to National Park: How the Gran Paradiso Became a Sanctuary for the Ibex.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2011), no. 1. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/2647.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2011 Wilko Graf von Hardenberg

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Hardenberg, Wilko Graf von. “Act Local, Think National: A Brief History of Access Rights and Environmental Conflicts in Fascist Italy.” In Nature and History in Modern Italy, edited by Marco Armiero and Marcus Hall, 141–158. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

- Passerin d’Entrèves, Pietro. Le Chasses Royales in Valle d’Aosta (1850–1919). Torino: Umberto Allemandi, 2000.

- Piccioni, Luigi. Il volto amato della Patria: Il primo movimento per la conservazione della natura in Italia, 1880–1934. Camerino: Università degli Studi di Camerino, 1999.

- Sievert, James. The Origins of Nature Conservation in Italy. Bern: Peter Lang, 2000.