On 9 July 1904, a crowd gathered in Nogojiwanong—colonially known as Peterborough, Ontario, Canada—to celebrate the official opening of the tallest hydraulic lift lock in the world, also “reputed to be the largest unreinforced concrete structure in the world” by Parks Canada. However, as Earl Lowes reports, “shortly before the opening ceremonies, there was a heavy thundershower and rain came down in torrents.” “Many of the crowd flocked into the liftlock [sic] tunnel and other sheltered areas to get out of the downpour” and although “a shoreline had been cleared and landscaped for [officials] to stand … [it] was never used for that purpose because the rain soaked the ground into a slippery mass of mud.”

The Peterborough Lift Lock on Odenaabe (Otonabee River).

The Peterborough Lift Lock on Odenaabe (Otonabee River).

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Peterborough Museum & Archives, 2000-012-002277-1.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

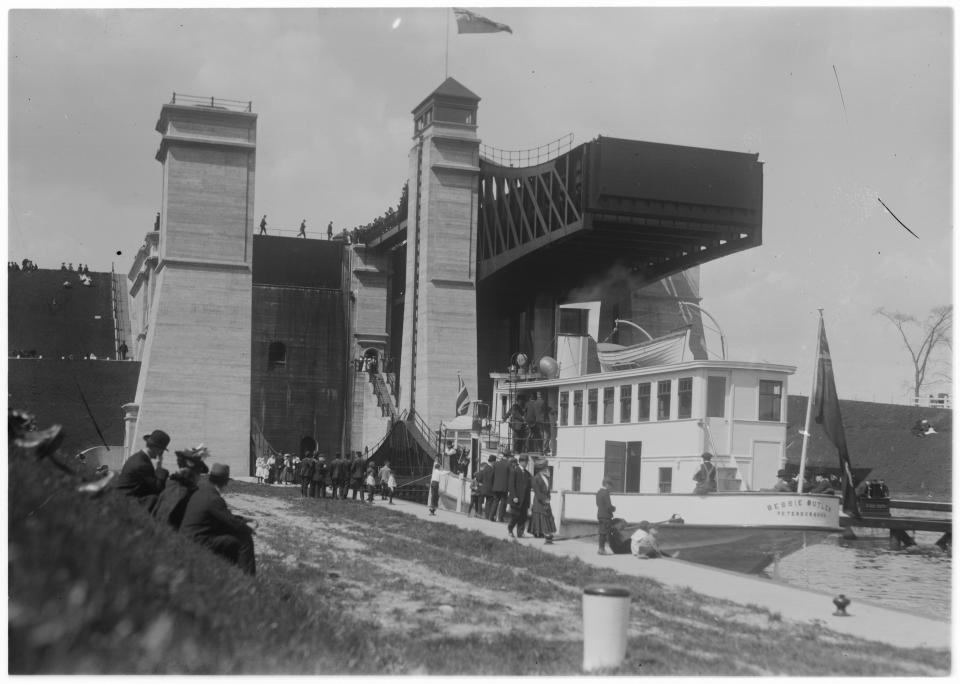

Steamer on the canal above the Peterborough Lift Lock.

Steamer on the canal above the Peterborough Lift Lock.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Peterborough Museum & Archives, 2000-012-016286-1.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This lift lock, built onto a river known as Odenaabe—colonially spelled “Otonabee”— was a crowning achievement of the Trent-Severn Waterway: a 386-kilometer-long system of locks, dams, and canals built onto waterbodies throughout what is colonially considered central Ontario, Canada, in order to connect Chi’Niibish (Lake Ontario) with Waasegamaa (Georgian Bay) on Odawa Zaagiigan (Lake Huron). The waterway was built to facilitate colonial settlement, resource extraction, and transportation, with construction lasting from 1833 to 1920.

However, while the Trent-Severn Waterway expanded access to central Ontario for settlers, it had devastating impacts on the Indigenous Nishnaabeg (also written as Anishinaabe) whose territory it cut through. Indigenous Nations throughout Ontario were already being dispossessed of their historic lands and forced to live on designated reserve lands, and the waterway caused extensive flooding of these and other lands. James T. Angus recounts that, in 1877, it was estimated that 20,000 to 25,000 acres of land could be reclaimed if one dam on Saagetay’achewan (Trent River) was removed. In 1912, Chief Dan Whetung of Curve Lake First Nation reported that his reserve “was originally 1,800 acres, and we lost 600 acres to flooding” (Gidigaa Migizi 2018: 80). And in his 2018 book, the late Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg Elder Gidigaa Migizi-ban (Doug Williams) notes that flooding particularly led to the loss of Nishnaabeg graves, sacred sites, and food sources—including manoomin or wild rice. Salmon and eels were also extirpated from the waters that the Trent-Severn Waterway was built onto after locks and dams cut them off from their spawning sites.

Canal above the Peterborough Lift Lock, Present Day, May 27, 2021.

Canal above the Peterborough Lift Lock, Present Day, May 27, 2021.

Photograph by Benjamin Kapron, 2021.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Peterborough Lift Lock, Present Day, May 28, 2023.

Peterborough Lift Lock, Present Day, May 28, 2023.

Photograph by Joseph Kapron, 2023.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

It is important, however, to not solely fixate on the settler-colonial violence manifested via the Trent-Severn Waterway, but to also acknowledge and respect how the Nishnaabeg and their other-than-human relations continue to survive and resist such violence. Gerald Vizenor, an Anishinaabe writer and scholar, advances the concept of “survivance” to highlight the dynamic and multifaceted forms of agency with which Indigenous Peoples survive against colonialism: Indigenous Peoples are not merely passively still alive despite settler colonialism; Indigenous Peoples continuously undertake strategies to survive against settler colonialism, maintaining their ways of life and relationships with land. As Vizenor puts it, survivance is “more than survival, more than endurance or mere response; the stories of survivance are an active presence … survivance is an active repudiation of dominance, tragedy, and victimry.”

Moreover, Mohawk and Anishnaabe scholar Vanessa Watts describes how the Anishinaabe recognize other-than-human beings to be “full of thought, desire, contemplation and will,” possessing an agency that “is not limited to innate action or causal relationships.” Because survivance emerges in this ontology of other-than-human agency, it is worth considering other-than-human beings as undertaking acts of survivance. The storm that hampered the opening of the Peterborough lift lock can be an example of such agential other-than-human survivance.

James T. Angus writes what is likely the closest there is to an “official” history of the Trent-Severn Waterway. Although Angus pays little attention to other-than-human beings, reading his book through the lens of survivance reveals how other-than-human survivance colors the history of the Peterborough lift lock and the rest of the Trent-Severn Waterway.

On 26 January 1906, “a section 40 feet wide broke away from the east bank of the canal” built to accommodate the Peterborough lift lock. This act of watery survivance “permit[ed] 500,000 gallons of water to pour into East Peterborough”: “Trees were uprooted, basements were flooded, a brick works was inundated, horses and cows found themselves standing in three or four feet of water, and squealing pigs and squawking hens were swept away by the sudden deluge, many of them to drown.”

Aftermath and damage of canal break above Peterborough Lift Lock.

Aftermath and damage of canal break above Peterborough Lift Lock.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Peterborough Museum & Archives, 2000-012-016398-1.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

When another lift lock on the Trent-Severn Waterway—in Kirkfield, Ontario, Canada—was tested in 1905, the rock, earth, and water rendered into the concrete agentially refused to behave as intended and “water poured through the walls at the rate of about 1 million gallons an hour.”

Even now, 120 years after the opening of the Peterborough lift lock, other-than-human beings continue to survive and resist it. Trees and plants grow along the lift lock canal, and stalactites have started to form in tunnels that run through the lift lock, offering hints of what the lift lock might become in the future.

Stalactites forming within Peterborough Lift Lock in 2021.

Stalactites forming within Peterborough Lift Lock in 2021.

Photograph by Benjamin Kapron, 27 May 2021.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

It is important to respect the agency in these other-than-human persons’ continued survival against the Peterborough lift lock, while not losing sight of all that was lost and unjustly interfered with through the construction of the Trent-Severn Waterway. Taking seriously the agency of other-than-human beings is not just an intellectual exercise: non-Indigenous scholars risk contributing to attacks on Indigenous ontologies, thereby reifying colonialism, if we dismiss other-than-human agency and fail to confront the anthropocentrism of dominant Western ontologies. Just as Nishnaabeg Leanne Simpson envisions the dismantling of the Trent-Severn Waterway, other-than human persons can offer lessons on what survival and resistance against the waterway—and settler-colonial violence more broadly—can look like.

How to cite

Kapron, Benjamin. “Other-than-Human Survivance Against the Trent-Severn Waterway.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2025), no. 4. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9935.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

2025 Benjamin Kapron

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Angus, James T. A Respectable Ditch: A History of the Trent-Severn Waterway, 1833–1920. Montreal, QC / Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988.

- Gidigaa Migizi (Williams, Doug). Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg: This Is Our Territory. Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books, 2018.

- Lowes, Earl. “Crowd was Drenched at Liftlock Opening.” Peterborough Examiner (Peterborough, ON), 9 July 1964.

- Parks Canada. “Peterborough Lift Lock National Historic Site of Canada.” Parks Canada Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Accessed 30 July 2024. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=486.

- Simpson, Leanne. Islands of Decolonial Love. Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books, 2013.

- Vizenor, Gerald. Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.