View of Mount Asama from Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Located between present-day Gunma and Nagano, Mount Asama erupted violently in the summer of 1783. A major eruption on 17 July was followed by ashfall reaching Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and, on 5 August, pyroclastic flows and lahars buried villages and sent volcanic debris surging into rivers as far as the Pacific coast.

View of Mount Asama from Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Located between present-day Gunma and Nagano, Mount Asama erupted violently in the summer of 1783. A major eruption on 17 July was followed by ashfall reaching Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and, on 5 August, pyroclastic flows and lahars buried villages and sent volcanic debris surging into rivers as far as the Pacific coast.

Photograph by 663highland. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In the summer of 1783, one of Japan’s most active volcanoes, Mount Asama, erupted with devastating force, sending pyroclastic flows, mudslides (lahars), and volcanic debris into surrounding river systems. Ashfall reached as far as Edo (modern-day Tokyo), worsening crop failures already caused by unseasonably cold weather and contributing to the Tenmei Famine (1782–1788), one of the most severe in Japan’s early modern history. Contemporary accounts describe darkened skies, clogged waterways, and ash falling for days. These cascading disasters brought immense suffering and widespread instability, touching the everyday lives of Edo’s residents and prompting large-scale political reforms.

In the years that followed, Edo’s popular illustrated comic books, kibyōshi, with their multi-layered characters, episodic narratives, and, by the standards of the time, realistic illustrations, offered readers a way to cope with turmoil not through protest, but through wit and imaginative engagement. Although often labeled “satirical” from a European perspective, the tone of kibyōshi in Edo-period Japan was light, clever, and fleeting, designed to provoke laughter at events rather than to reform politics or society. These picture books provided much-needed levity, helping readers release social anxiety and return to daily life.

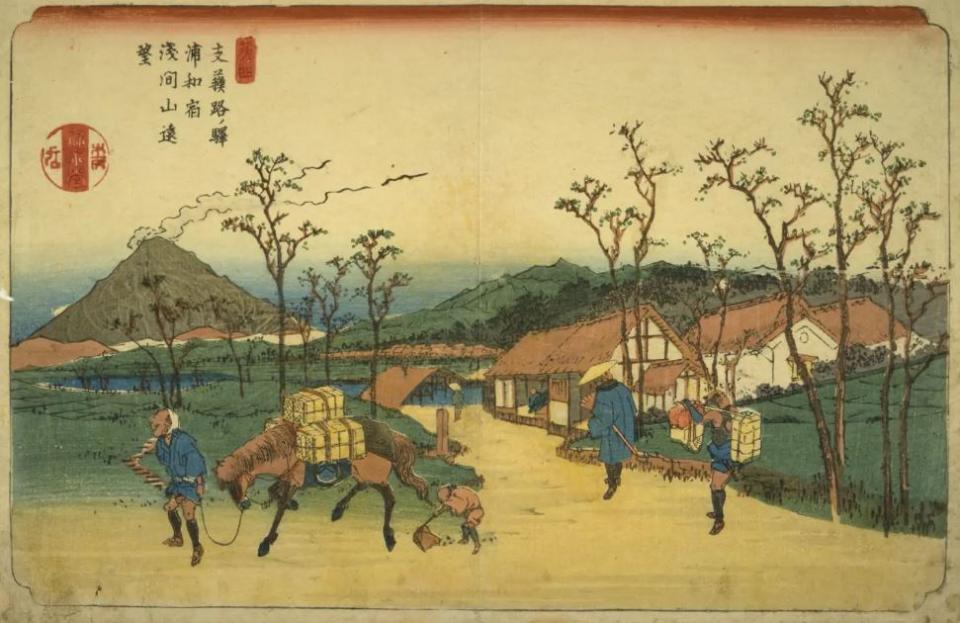

Urawa Station, View of Mount Asama in the Distance, from The Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaidō ( 支蘇路ノ駅浦和宿浅間山遠望, Dai-yon Shisoro no Eki Urawa-juku Asamayama Enbō). This woodblock print shows travelers and a packhorse heading toward the smoking Mount Asama, capturing both the rhythm of daily travel and the looming presence of natural forces. Urawa-juku, located approximately 27 kilometers from Edo (present-day Tokyo), was the third post town from Nihonbashi on the Nakasendō, the inland highway connecting Edo and Kyoto through Japan’s central mountains.

Urawa Station, View of Mount Asama in the Distance, from The Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaidō ( 支蘇路ノ駅浦和宿浅間山遠望, Dai-yon Shisoro no Eki Urawa-juku Asamayama Enbō). This woodblock print shows travelers and a packhorse heading toward the smoking Mount Asama, capturing both the rhythm of daily travel and the looming presence of natural forces. Urawa-juku, located approximately 27 kilometers from Edo (present-day Tokyo), was the third post town from Nihonbashi on the Nakasendō, the inland highway connecting Edo and Kyoto through Japan’s central mountains.

Woodblock print by Keisai Eisen, n.d. Courtyesy of NDL Digital Collections. Click here to view source.

Kibyōshi reflected, above all, the perspectives of townspeople and lower-ranking samurai in the service of feudal lords, rather than the shogunate elite, who experienced the famine’s impact but saw the eruption itself only from a distance. Even so, Mount Asama’s eruption became part of a shared cultural memory that shaped how the hardships of the Tenmei era were interpreted and remembered.

Initially, disasters like the eruption and famine were not treated as subjects of comic storytelling. It was only after the start of the Kansei Reforms in 1787, one of the three major political reform movements of the Edo period, led by Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829), that kibyōshi began to revisit and reinterpret these events. These later works reflected popular hardship and rising tensions between old and new regimes. Yet the motif of ash turning into gold had already emerged by 1785. In Kiruna no Ne kara Kanenonaru Ki, a title whose palindrome means “Do Not Cut the Tree That Grows Money from Its Roots,” fire and destruction are ironically shown to bring prosperity, as gold coins fall from burning houses. The twist parodies the idea of disaster yielding fortune and mocks the era’s obsession with money.

Tenka Ichimen Kagami no Umebachi (天下一面鏡梅鉢, 1789) imagines an idealized world ruled by a virtuous emperor and advisor, where volcanic ash turns to gold, beggars wear silk, and courtesans quote Confucius. This sharp satire critiques corruption, food shortages, and inequality in late eighteenth-century Japan. The kibyōshi translations here follow a new method that I am developing for early modern Japanese visual-narrative texts, detailed in Orpheus Noster (forthcoming).

Tenka Ichimen Kagami no Umebachi (天下一面鏡梅鉢, 1789) imagines an idealized world ruled by a virtuous emperor and advisor, where volcanic ash turns to gold, beggars wear silk, and courtesans quote Confucius. This sharp satire critiques corruption, food shortages, and inequality in late eighteenth-century Japan. The kibyōshi translations here follow a new method that I am developing for early modern Japanese visual-narrative texts, detailed in Orpheus Noster (forthcoming).

Illustration by Eishōsai Chōki, 1789. Colorized, edited, and translated by Andrea Csendom. Original image courtesy of General Library, The University of Tokyo, Japan. Click here to view original image.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

While kibyōshi did not aim to change the world order, linking gold to volcanic ash carried a political edge. In Tenka Ichimen Kagami no Umebachi (“The Mirror of the Realm: The Plum Flower Crest,” see image), the aftermath of the eruption is subtly connected to rising social unrest, including the 1787 rice riot in Edo, where merchants were accused of hoarding grain and selling it at exorbitant prices during a time of extreme scarcity. The 1788 work Yare Deta, Sore Deta: Kamenoko ga Deta yo (“Here It Comes, There It Comes: The Baby Turtle Appears”) takes up this theme more directly and humorously. Playing on the pun between kame (turtle) and kome (rice), the story satirizes food shortages by depicting merchants selling turtles as a substitute for suppon. This soft-shelled turtle had become popular as an affordable and nourishing food in this era. In a playful twist, a group of soft-shelled turtles rescue a captured “rice” turtle, parodying grassroots resistance and the confusion between genuine needs and official ideals during famine.

The image of ash turning into gold also appears in Kōshi-jima Toki ni Aizome (“Confucian Stripes Dyed Blue at the Right Time,” 1789, see image), where ash from distant Mount Asama reaches Edo and transforms into coins. The story envisions an idealized society under the Kansei Reforms, but this utopia is ironically set against the harsh reality of commoners struggling under strict frugality policies. Even if gold were to fall from the sky, it would be nothing but ash, worthless in a world where survival depended not on wealth but food.

Kōshi-jima Toki ni Aizome (孔子縞于時藍染, 1789) mocks the Kansei Reforms by comparing the spread of Neo-Confucian values to a passing fashion trend. The title plays on the word kōshi-jima (plaid), replacing its characters with “Confucius” and “timely indigo dyeing,” suggesting that moral teachings were dyed into society like cloth. The translation follows a new method that emphasizes the satire’s deeper cultural critique over literal transcription of the original stylized text.

Kōshi-jima Toki ni Aizome (孔子縞于時藍染, 1789) mocks the Kansei Reforms by comparing the spread of Neo-Confucian values to a passing fashion trend. The title plays on the word kōshi-jima (plaid), replacing its characters with “Confucius” and “timely indigo dyeing,” suggesting that moral teachings were dyed into society like cloth. The translation follows a new method that emphasizes the satire’s deeper cultural critique over literal transcription of the original stylized text.

Illustration by Masaaki Kitao, n.d. Colorized, edited, and translated by Andrea Csendom. Courtesy of NDL Digital Collections. Click here to view the original image.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The irony was sharp. What people truly needed was rice, not riches. Yet in the story, people still scramble to gather the falling gold coins. The comic spirit targets not only the government’s unrealistic ideals but also the people who follow official values without question, chasing illusions rather than confronting the reality of their needs.

However, rather than advocating reform, these books helped many common people endure uncertainty, precisely because they were widely read. As annual bestsellers released for the New Year, kibyōshi became part of the seasonal rhythms of Edo life, reflecting the cycles of hardship and renewal that marked the late eighteenth century. Their lightness was not a call to action, but a form of emotional release. In a world buried in ash, they imagined gold, not as fantasy, but as laughter that helped people carry on. This ability to confront disaster with wit rather than despair sets early modern Japanese visual comic tradition apart from its European counterparts. Because Japan’s natural environment and disaster risks have remained largely unchanged, the deeply rooted cultural approach of meeting catastrophe with resilience and perseverance has endured since the early modern period. This mindset continues to shape how Japanese society responds to crisis today.

Animated with AI tools, this video reimagines an 18th-century Japanese comic book scene, gold erupting from a volcano during a famine, as satirical commentary on the Kansei reforms.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) under the Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (Grant Number: 23KF0217), for the project titled “Translating Culture: From the Commoners of Edo to the Global Present.”

How to cite

Csendom, Andrea. “Turning Ash into Gold: The 1783 Mount Asama Eruption and the Tenmei Famine in Early Modern Japanese Satire.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2025), no. 7. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9953.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2025 Andrea Csendom

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Carroll, Morgan Pitelka. “Benevolence, Charity, and Duty: Urban Relief and Domain Society during the Tenmei Famine.” Monumenta Nipponica 69, no. 1 (2014): 55–101. doi:10.1353/mni.2014.0013.

- Kern, Adam L. Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Laura Morettei and Satō Yukiko, eds. Graphic Narratives from Early Modern Japan: The World of Kusazōshi. Leiden: Brill, 2024.

- Mizuno, Tatsuki, Fukashi Maeno, and Atsushi Yasuda. “Transition from Growth to Collapse of the Plinian Column during the 1783 Eruption of Asama Volcano, Japan, Inferred from Rock Microtextures.” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 462 (2025). doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2025.108310.

- Nakazawa-Csendom, Andrea. The Kibyōshi of Reform-period in the Context of History of Thought, and Exploring its Translation Method: Source Analysis to Complement Research History. Doctoral dissertation, Doctoral School of Linguistics, Budapest, 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/10831/58169.