The waters of the Venice Lagoon have always risen and fallen with the wind and tides. After rapid industrialization in the postwar period, however, the nature of the lagoon seemed to change, and in November 1966 an extreme flooding event struck Venice. It is still undetermined whether the flood water was more violent because of land reclamation, groundwater extraction, or a new shipping lane carved through the heart of the lagoon. Nevertheless, as the water receded, Venice seemed more fragile than ever.

The MOSE panels at dawn, with the Dolomites present in the background. A rare sight captured by resident Paola Juris, who said “I heard the bora blowing in Venice at 5:30 and knew the barrier would be raised. I imagined that from Lido the mountains would be visible behind MOSE. It was true, and I ran desperately to the vaporetto, making the last trek on foot because there wasn’t an early bus. I went alone through the blackberry brambles and pine trees while the sun was rising. And I guessed correctly, the visibility with that type of wind was perfect. It was two degrees Celsius.”

The MOSE panels at dawn, with the Dolomites present in the background. A rare sight captured by resident Paola Juris, who said “I heard the bora blowing in Venice at 5:30 and knew the barrier would be raised. I imagined that from Lido the mountains would be visible behind MOSE. It was true, and I ran desperately to the vaporetto, making the last trek on foot because there wasn’t an early bus. I went alone through the blackberry brambles and pine trees while the sun was rising. And I guessed correctly, the visibility with that type of wind was perfect. It was two degrees Celsius.”

© Paola Juris. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

So it was that in 1973 the Italian state adopted a mandate to “safeguard” Venice, calling it a site of “national interest” (Decreto 117/1973). After years of debate, a special committee decided that a flood-barrier project known as MOSE (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico) would be constructed by a group of businesses called Consorzio Venezia Nuova (CVN). The chosen design was a set of 78 panels that could swing upwards, keeping high tides out of the Venice Lagoon.

During these decades of back-and-forth over MOSE, Venetians who remembered the 1966 flood and the environmental controversy that followed were dismayed that the state was proposing a high-impact project to address flooding that, in their view, was caused by earlier high-impact interventions in the lagoon system.

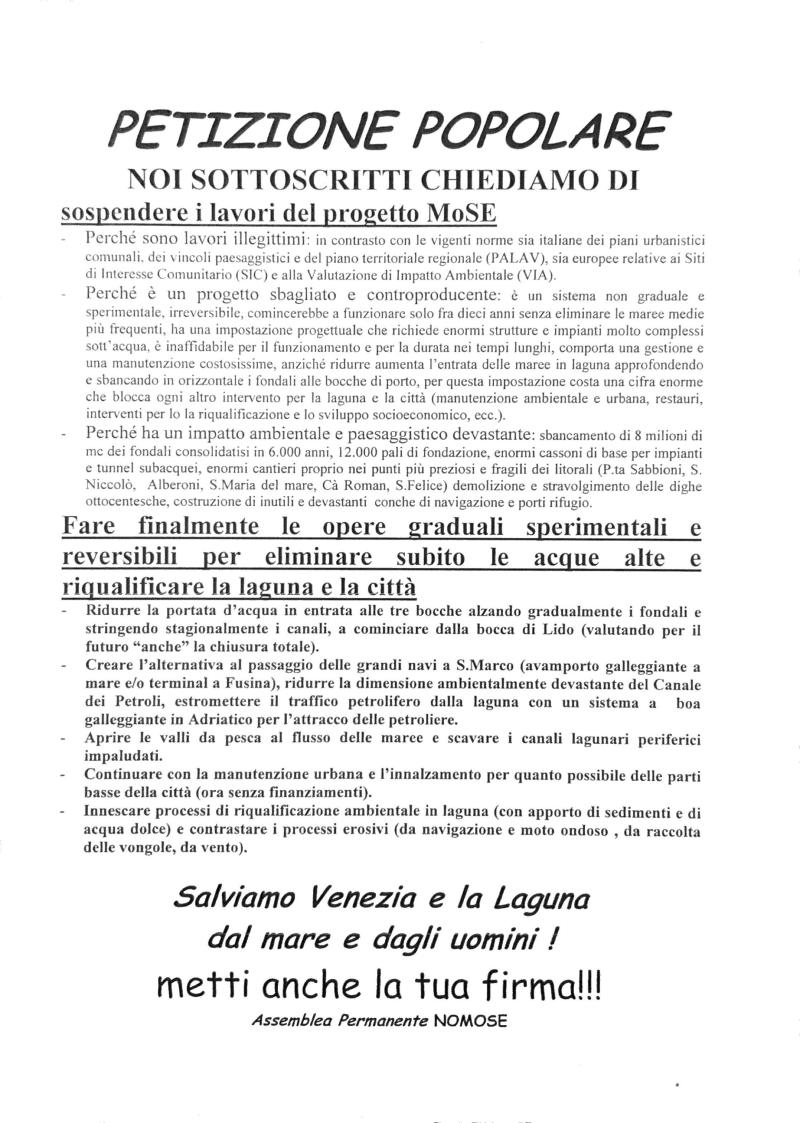

In 2005, the NoMOSE assembly—made up of students, environmental activists, and concerned citizens—circulated a petition with two requests. First, “to suspend work on the MOSE project.” Second, “to make gradual, experimental, and reversible projects to immediately eliminate high water events and redevelop the lagoon and the city.” The petition criticized past political dealings (the project was illegitimate, they said, because it violated local planning codes and had not received approval on its environmental impact assessment) and looked to alternatives, which were listed on the petition: to make the lagoon mouths more shallow, to redirect large ships to an offshore port, to prevent erosion where deep canals had been dug, or to raise the lowest parts of the islands. They made clear that these alternatives would help maintain the coastal ecosystem and could be completed quickly, with a fraction of the public funds used for MOSE.

Petition circulated by the NoMOSE assembly from late 2005 to early 2006, eventually receiving 12,500 signatures.

Petition circulated by the NoMOSE assembly from late 2005 to early 2006, eventually receiving 12,500 signatures.

© Stefano Micheletti. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In March 2006, a NoMOSE delegation took the petition to the EU court in Brussels. Having collected 12,500 signatures, roughly one-sixth of the combined population of Venice’s islands, they testified before a commission about the devastating environmental impact of the MOSE project. Their bid eventually pushed the EU to require CVN to perform “compensation works” for the damages. The resulting habitat restoration, still ongoing, is important but falls short of offsetting MOSE’s impact: As fishermen and other residents observe, the MOSE works have changed the very tides and currents in the lagoon. During early construction of MOSE, the EU court could not block a major project of a member state, and so the petition was not able to take any legal action.

As formal participation failed, the NoMOSE assembly turned to protest. In September 2005, they delivered a tire and a can of motor oil, objects stolen from the MOSE construction site, to the CVN offices in Venice. They told reporters that they wanted to highlight the double standard of state projects. “Our damages, as you can see, are reversible, while the mess they make is irreversible,” quipped an activist. “Reversibility” was supposed to be a legal requirement for the project, but NoMOSE showed that the state’s plan was not reversible at all: far out of line with the Venetian ethic of scomenzèra, centered on making low-impact lagoon interventions.

Occupation of the MOSE San Niccolò construction sites on the morning of 6 September 2005, led by the NoMOSE assembly and the No Global Beach project. Police would charge 29 of the “disobedients” with infractions and fines.

Occupation of the MOSE San Niccolò construction sites on the morning of 6 September 2005, led by the NoMOSE assembly and the No Global Beach project. Police would charge 29 of the “disobedients” with infractions and fines.

© Stefano Micheletti. Used by permission.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Media and local authorities at first treated the NoMOSE assembly as “disobedients,” and 29 people were charged with trespassing after the September 2005 action. NoMOSE denounced CVN’s fear-mongering tactics and urged the courts to “be more attentive to the colossal damages happening under everyone’s eyes rather than persecuting alleged crimes.”

Further NoMOSE protests added to the pressure to stop construction. On 29 April 2006, activists took boats to Lido—accompanied by the “Ride of the Valkyries” on loudspeakers—to “desecrate” the MOSE construction sites. There, they spread corn, tomato, and “marijuana” (common grass) seeds in homage to a line by local band Pitura Freska. The summer of 2006 was particularly active. NoMOSE made a “blitz” on the artificial island at Lido on 13 July. They occupied the construction sites at San Niccolò on 19 July. They put a flag on the top of a crane on 10 August. With each headline, the assembly won symbolic media victories that held open the possibility of halting the flood-barrier project.

Occupation of temporary construction sites at the Lido lagoon mouth on 10 August 2006. Protestors in boats heckled local police while activists in harnesses scaled the crane.

Occupation of temporary construction sites at the Lido lagoon mouth on 10 August 2006. Protestors in boats heckled local police while activists in harnesses scaled the crane.

© Stefano Micheletti. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Protesters hang a NoMOSE flag from a crane during the 10 August 2006 occupation of the MOSE operations at Lido.

Protesters hang a NoMOSE flag from a crane during the 10 August 2006 occupation of the MOSE operations at Lido.

© Stefano Micheletti. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Despite local opposition, the Prodi government definitively approved the MOSE project in November 2006. The NoMOSE assembly has since turned its attention to monitoring environmental concerns in the lagoon. By the 2010s, its members reformed under the name No Grandi Navi, the movement against cruise ships in Venice. After two decades of construction (and an enormous corruption scandal in 2014), the MOSE system was first activated in October 2020, 10 years behind schedule, with a final cost of six billion euros, not counting ongoing operational expenses.

My colleagues and I have spoken with former NoMOSE activists about the current state of lagoon politics. They are still upset about the way the state ignored their suggestions about how to make different interventions. Their claim that MOSE is another irreversible alteration to lagoon hydrology has accumulated significant evidence, thanks to the work of Luigi D’Alpaos, Luana Zanella, and others. Yet, their protests go unheard by politicians and MOSE engineers, who for their part are confident that the project protects Venice for now, but are less sure about what will come next.

Public participation by the NoMOSE assembly temporarily hijacked the state’s dominant narrative of MOSE as a project that would “safeguard” the lagoon. Instead, activists turned the project into an issue of “cognitive injustice,” where dominant claims in favor of state interests corrupted the possibility for outcomes that work primarily to maintain a balance between human and nonhuman systems. By reorganizing citizen knowledge in a debate about the future of the lagoon ecosystem, which is also their home, the NoMOSE assembly insisted on a critical analysis of power relations, asking: “Who gets to decide our fate?”

How to cite

Turner, Holden. “NoMOSE: Contested Flood Barriers in Venice, Italy” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2025), no. 8. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9986.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2025 Holden Turner

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Giupponi, Carlo, Marco Bidoia, Margaretha Breil, Luca Di Corato, Animesh Kumar Gain, Veronica Leoni, Behnaz Minooei Fard, Raffaele Pesenti, and Georg Umgiesser. “Boon and Burden: Economic Performance and Future Perspectives of the Venice Flood Protection System.” Regional Environmental Change 24, no. 2 (2024): 44. doi.org/10.1007/s10113-024-02193-9.

- Iovino, Serenella. Ecocriticism and Italy: Ecology, Resistance, and Liberation. Environmental Cultures Series. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Mencini, Giannandrea. Venezia Acqua e Fuoco: La Politica Della “Salvaguardia” Dall’alluvione Del 1966 al Rogo Della Fenice. Il Cardo, 1996.

- Porzionato, Monica. “Assemblages in the Venetian Lagoon: Humans, Water and Multiple Historical Flows.” Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures 15, no. 1 (2021). doi.org/10.21463/shima.106.

- Testa, Silvio. “Una Rondine Non Fa Primavera.” In Voci: Echi: Laguna, edited by Lorenzo Fabian, Marta De Marchi, Luca Iuorio, and Maria Chiara Tosi. Serie City Lab, no. 0. Anteferma, 2021.

- Turner, Holden. “After MOSE: Working Lagoonscapes + Living with Sea Level Rise.” Master’s thesis, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, 2024.

- Vianello, Rita. “The MOSE Machine: An Anthropological Approach to the Building of a Flood Safeguard Project in the Venetian Lagoon.” Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures 15, no. 1 (2021). doi.org/10.21463/SHIMA.104.