The Pasterze glacier in the Hohe Tauern National Park

The Pasterze glacier in the Hohe Tauern National Park

2012 Rene Rivers

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

Between 1981 and 1992 the Austrian federal states of Carinthia, Salzburg, and Tyrol established the Hohe Tauern National Park in the Alpine mountain range of the same name. As the country’s first national park the reserve occupies a model position in Austria. In a larger spatial framework, however, the pioneer park can be seen as a latecomer with all neighboring Alpine countries having older national parks.

Kingfisher and wallcreeper as icons for Verein Naturschutzpark’s ambitions to create nature parks in the “typical German landscapes” of heath (Lüneburger Heide) and Alps (Hohe Tauern)

Kingfisher and wallcreeper as icons for Verein Naturschutzpark’s ambitions to create nature parks in the “typical German landscapes” of heath (Lüneburger Heide) and Alps (Hohe Tauern)

All rights reserved © Illustration from 1913, Verein Naturschutzpark.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

There is no simple explanation, neither for the long delay nor for the eventual establishment of Hohe Tauern National Park. Attempts to establish a park in this region go back to the era of the Austrian monarchy. In 1913 and 1914, the German-Austrian Verein Naturschutzpark [conservation park association] bought several alms in the Salzburg part of the Hohe Tauern, with a total area of approximately 1,000 hectares, to spare these spots from agricultural or industrial use. However, the association’s plans for a larger “nature protection park” faltered with the First World War, which put a damper on conservation efforts across Europe.

In the interwar years, private associations such as the German-Austrian Alpine Association, the Austrian League for Nature Protection, or the socialist Friends of Nature became involved in nature protection in the Hohe Tauern. After the German Reich had annexed Austria in 1938, the National Socialist conservation elite selected Hohe Tauern as a prime site for a future “Greater German National Park.” Authorized by Hermann Göring, Berlin Zoo director Lutz Heck pushed the issue, but with the beginning of the war his plans were shelved.

Postwar nature idyll: The “Musteralm” Schidhofalm in the Obersulzbachtal, photographed by leading Austrian conservationist Lothar Machura (1950)

Postwar nature idyll: The “Musteralm” Schidhofalm in the Obersulzbachtal, photographed by leading Austrian conservationist Lothar Machura (1950)

All rights reserved © 1950 Lothar Machura, Verein Naturschutzpark

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

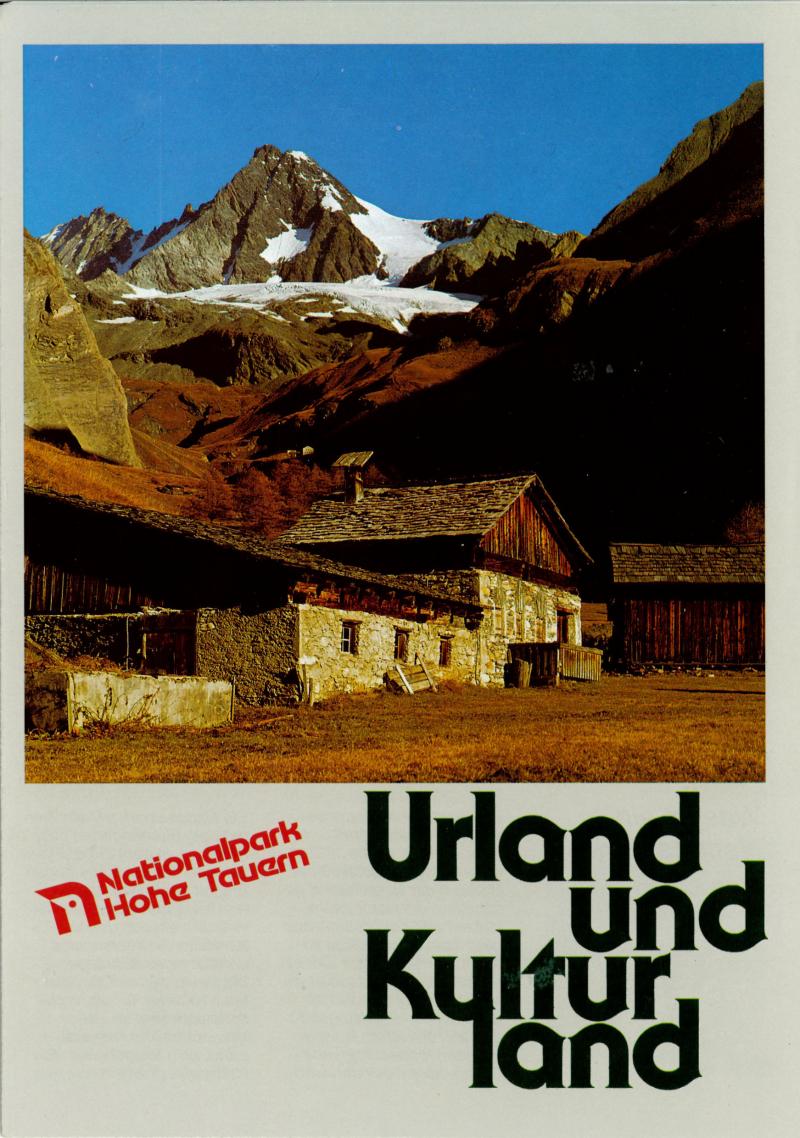

Incorporating both cultural landscapes and wilderness areas was key to the establishment of the park (Pamphlet 1985)

Incorporating both cultural landscapes and wilderness areas was key to the establishment of the park (Pamphlet 1985)

All rights reserved © 1985 Hohe Tauern National Park Committee.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In the post-war decades of reconstruction and growing prosperity different visions of development clashed. Ideas for strengthening nature protection were both driven and challenged by large infrastructure projects, mainly concerning water power, road construction, and an oil-pipeline, by agricultural intensification, and by tourism. As in the decades before, these issues were not restricted to the region or nation but influenced by international and global developments.

When the Council of Europe declared 1970 the “European Nature Conservation Year,” this provided a strong impetus for the national park idea. In 1971 the first concrete political step was taken when the governors of Carinthia, Salzburg, and Tyrol signed an agreement on a future national park. The idea was finally realized in the 1980s and 1990s at state level, which resulted in the creation of today’s three park administrations.

Besides the upheavals caused by war, harmonizing (or deflecting) social interests was the main reason for the time-consuming process of achieving the designation of the national park. Bringing proponents and opponents closer together and mediating between local needs and international standards took many very small steps. Hardly any other national park featured as many land owners who needed to be convinced of the significance and benefits of such a project. A 1995 mission statement called it “a miracle of spatial planning and conservation.” This miracle did not come about through divine or human intervention but was the result of endless talks and of mobilizing new sources of income for the region.

Map of the Hohe Tauern National Park

Map of the Hohe Tauern National Park

Anitagraser

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

How to cite

Kupper, Patrick and Wöbse, Anna-Katharina. “A Latecoming Pioneer: Austria’s Hohe Tauern National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2014), no. 9. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/6233.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2014 Patrick Kupper and Anna-Katharina Wöbse

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Kupper, Patrick and Anna-Katharina Wöbse. Geschichte des Nationalparks Hohe Tauern. With contributions by Ute Hasenöhrl, Georg Stöger, Ortrun Veichtlbauer, Ronald Würflinger. Innsbruck: Tyrolia, 2013.

- Kupper, Patrick et al. History of Hohe Tauern National Park: A Case In Point of Use and Protection. eco.mont 6:1, (January 2014): 61–64.