On Christmas morning 1953, an express train from Wellington, New Zealand, was meant to arrive in Auckland. It never did. At 11:21 p.m. the previous evening, it plunged into the Whangaehu River at Tangiwai in the central North Island. Of the 285 passengers on board, 151 died, eclipsing the 21 fatalities at Hyde in 1943 to make it New Zealand’s worst railway disaster—and one of the world’s worst.

The locomotive, one of the bridge girders, and part of the third carriage, 25 December 1953.

The locomotive, one of the bridge girders, and part of the third carriage, 25 December 1953.

Unknown photographer, 25 December 1953.

Courtesy of Archives New Zealand, AAVK W3493 D-1015.

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

The wreckage of the second carriage sits in the foreground; to the left is the largely intact first carriage, 27 December 1953.

The wreckage of the second carriage sits in the foreground; to the left is the largely intact first carriage, 27 December 1953.

Unknown photographer, 25 December 1953.

Courtesy of Archives New Zealand, AAVK W3493 D1812.

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand’s largest active volcano, towers above the Central Plateau. Its peak Tahurangi is the North Island’s highest point at 2,797 meters. Ruapehu’s crater lake is the Whangaehu’s headwaters and it is partly fed from the North Island’s only glaciers. An eruption in 1945 formed a tephra dam, behind which the lake grew in volume. The dam collapsed on 24 December 1953, unleashing a lahar—a thick torrent of water, mud, and volcanic debris—down the river.

The North Island Main Trunk Railway—a primary transport artery between New Zealand’s capital, Wellington, and its largest city, Auckland—crosses the Whangaehu at a village called Tangiwai, “weeping waters” in Māori. The express reached the bridge at the lahar’s peak flow. Cyril Ellis, a motorist who discovered the nearby road bridge was out, tried to alert the crew of the oil-fuelled steam locomotive KA 949, driver Charles Parker and fireman Lance Redman. They shut off steam, applied the emergency brakes, and sanded the tracks—but could only save half the train. Parker and Redman remained at their controls, riding the locomotive into the torrent. The first five carriages followed, all second-class; the sixth, the leading first-class carriage, teetered on the shattered bridge until it too fell. Three more first-class carriages, a postal van, and the guard’s van remained on the tracks. Both Parker and Redman died, as did one occupant of the leading first-class carriage and 148 of the 176 second-class passengers.

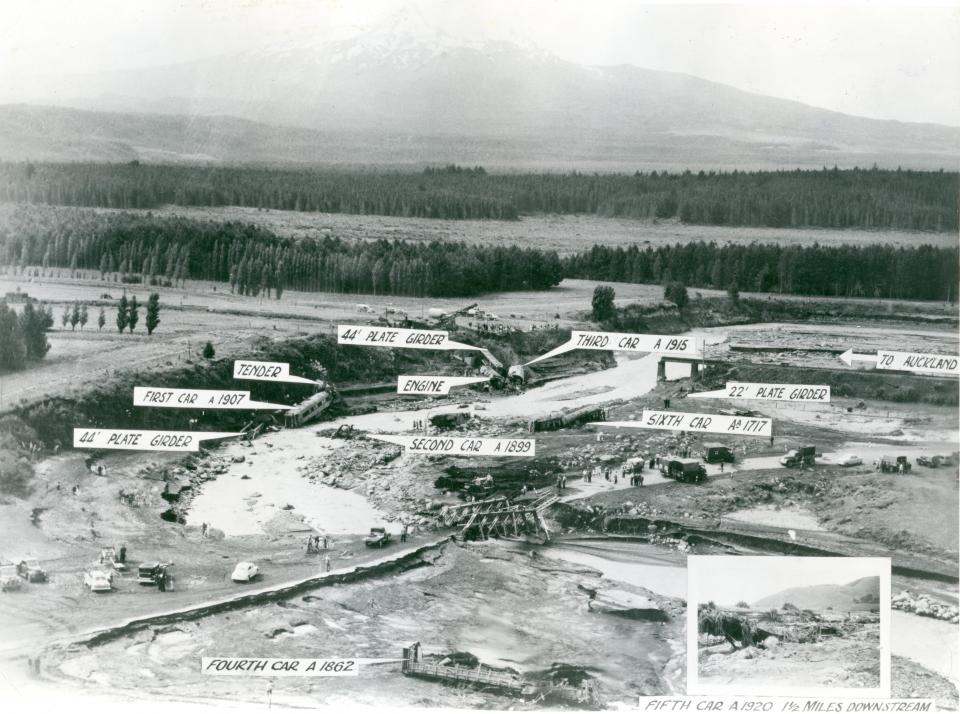

Labeled press photograph of the site of the tragedy, looking towards Mount Ruapehu, 25 December 1953.

Labeled press photograph of the site of the tragedy, looking towards Mount Ruapehu, 25 December 1953.

Unknown photographer, 25 December 1953.

Courtesy of Archives New Zealand, AAVK W3493 E-982.

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

New Zealand’s railways had long experience of flooding but little of lahars. Railways modified rivers nationwide: embankments divided floodplains, riverbanks were stabilized to mitigate erosion, braided rivers were dredged to concentrate their flows. Rivers in turn modified railway routes, undermined their formation, and flooded across lines. The Whangaehu’s name describes a turbid river mouth, referring to discoloration from volcanic discharge that also earned the river its nickname of “Sulphur Stream.” At least four lahars filled the Whangaehu between 1840, when formal British settlement of New Zealand began, and 1953. Only one occurred after the railway’s 1908 opening: this torrent in 1925 damaged but did not destroy the bridge. Some recent assessments, such as British journalist Benedict le Vay’s 2013 account—a useful but idiosyncratic book of digressions, unclear sourcing, and generally uncontroversial conclusions presented as original insight—have suggested the New Zealand Railways were negligent in assessing risk. But lahars were rare and poorly understood. Large-scale disaster at Tangiwai was beyond imagination.

The 1953 lahar is not the largest recorded in the Whangaehu, but its arrival at Tangiwai almost simultaneously with the express meant it had the greatest effect. Passengers were immersed in sulphuric and muddy water. Pungent oil from the locomotive added to this foul cocktail. Survivors never forgot its smell or consistency. Joan Karam, who escaped the third carriage, struggled to endure the water’s icy temperature—an indicator of its glacial origins. Richard Edward “Ted” Brett, a young plumber, was swept to a sheltered part of the river and used rock-climbing experience to surmount the riverbank. For the rest of his life the smell of oil fumes would feel like an unbearable attack upon his body.

Tangiwai as seen in 2018, looking from the disaster memorial up the Whangaehu River to the new railway bridge. The first carriage came to rest on the bank at left, the second carriage in the bend of the river.

Tangiwai as seen in 2018, looking from the disaster memorial up the Whangaehu River to the new railway bridge. The first carriage came to rest on the bank at left, the second carriage in the bend of the river.

Photograph by André Brett.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The new bridge built after the disaster still carries the North Island Main Trunk Railway across the Whangaehu River. The ill-fated express approached from the opposite bank.

The new bridge built after the disaster still carries the North Island Main Trunk Railway across the Whangaehu River. The ill-fated express approached from the opposite bank.

Photograph by André Brett.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Tangiwai demonstrates acutely the class dimensions common to environmental disasters: only 28 of 176 second-class passengers survived, compared to 108 of 109 in first class. The first-class carriages were marshaled far from the locomotive’s noise and smoke—and from danger. Up front the second-class carriages were torn apart. The fifth carriage was carried 2.5 kilometers downriver; the second carriage, turned repeatedly within the torrent, was unrecognizable—with Ted Brett its only survivor. Remarkably, his plumbing equipment, which he was carrying to perform repairs for a relative, was recovered intact and usable at the Whangaehu’s mouth.

The anonymizing effects of mud and grime accentuated the traumatic task of identifying victims. Twenty, never found, are believed to have been carried out to sea. Desmond Capper’s family viewed many bodies in the hope of identifying him, without success. The Cockburn family could bury one of their dead, Douglas, but all that remained of brother John were tickets from his shirt pocket.

Tangiwai left an indelible mark on New Zealand; the name is synonymous with disaster. It has stimulated a small corpus of works wrestling with loss and mortality. These include numerous iterations of the story of New Zealand cricketer Bob Blair batting against South Africa after learning his fiancée had perished. Others recount personal stories: Trish Gray losing her grandparents; James Rowe’s experiences as a local telegrapher. Many highlight nature’s perceived caprice. The environment brings tragedy; incomplete knowledge and class considerations recede. John Archer, who grew up downriver, penned folksong “Pillows of the Dead” to honor that awful Christmas of his childhood. The disaster is an unfathomable working of the Whangaehu:

Well, my pillow case was bulging,

Full of presents, by my bed—

Then the river brought those pillows of the dead

Tangiwai both shaped and fits a narrative of environmental tragedies in New Zealand as unforeseen and sudden. This is somewhat inaccurate and shorn of its class dimension, but it resonates with personal experiences of disruptive horror.

A memorial listing the 151 victims was erected in 1989; the flower stations dedicated to survivors were added this decade.

A memorial listing the 151 victims was erected in 1989; the flower stations dedicated to survivors were added this decade.

Photograph by André Brett.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A memorial for locomotive driver Charles Parker and fireman Lance Redman was dedicated in May 2017.

A memorial for locomotive driver Charles Parker and fireman Lance Redman was dedicated in May 2017.

Photograph by André Brett.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

How to cite

Brett, André. “Lahar Meets Locomotive: New Zealand’s Tangiwai Railway Disaster of Christmas Eve 1953.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2018), no. 31. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8476.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 André Brett

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Conly, Geoff, and Graham Stewart. New Zealand Tragedies on the Track: Tangiwai and Other Railway Accidents, rev. ed. Wellington: Grantham House, 1991.

- Hutchins, Graham, and Russell Young. New Zealand’s Worst Disasters: True Stories That Rocked a Nation. Auckland: Exisle Publishing, 2015.

- Knight, Catherine. New Zealand’s Rivers: An Environmental History. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2016.

- Manville, V., K. A. Hodgson, and I. A. Nairn. “A Review of Break-Out Floods From Volcanogenic Lakes in New Zealand.” New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 50, no. 2 (2007): 131–50.

- New Zealand Railways. Tangiwai Railway Disaster Report of the Board of Inquiry. Wellington: Government Printer, 1954.

- Stewart, Graham. The Tangiwai Disaster: A Christmas Eve Tragedy. Wellington: Grantham House, 2003.

- le Vay, Benedict. Weeping Waters: When Train Meets Volcano. London: One Particular House, 2013.