On 9 February 1946, a fifty-foot wall of water carrying huge cedar logs engulfed Paronella Park, wreaking havoc on the Moorish-style castle and its surroundings. Located close to cascading falls on the banks of Mena Creek, south of Cairns, the Park was described in 1936 by the Cairns Post newspaper as “the most interesting playground in Queensland.” When the water dispersed, the dream of Catalonian migrant José Paronella lay ruined. This was a human-made catastrophe.

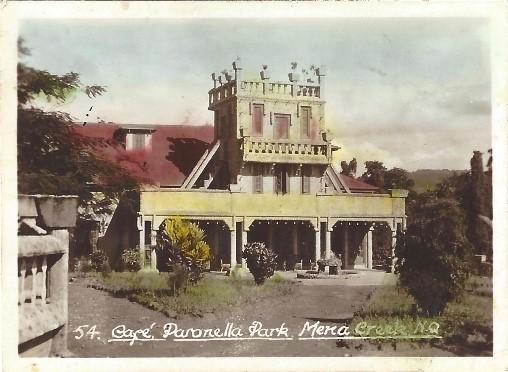

The castle at Paronella Park.

The castle at Paronella Park.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Paronella Park Photograph Collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The story of Paronella Park demonstrates themes common to European settlement in tropical areas. Migrants like Paronella, though resilient and appreciative of the unique character of the tropical environment, often failed to realize the unsuitability of their attempts to impose European cultural practices on those environments. That, combined with a paucity of meteorological data and ignorance of weather patterns, had disastrous consequences. Consequently, as argued by Don Garden in his Droughts, Floods and Cyclones: El Niños that Shaped our Colonial Past and Julia Elizabeth Miller in her PhD thesis “Scorchers and Soakers: A Cultural History of El Niño Southern Oscillation in New South Wales, 1900–1990,” the effects of weather events were frequently compounded by human-induced factors.

Between November and April, cyclones and flooding are common in tropical Queensland. The results are often catastrophic. On the weekend of 9–10 February 1946, a cyclone crossed the coast at Cardwell, wreaking damage and causing flooding. In its path were sugar-growing districts that were still being cleared of timber for an expanding sugar industry. The Mena Creek area was particularly well forested. Upstream of Paronella Park, loggers had been felling red cedars coveted for their rich-colored timber. They piled the logs on low ground bordering the creek to await transport to sawmills. They were a disaster waiting to shatter Paronella’s “dream.”

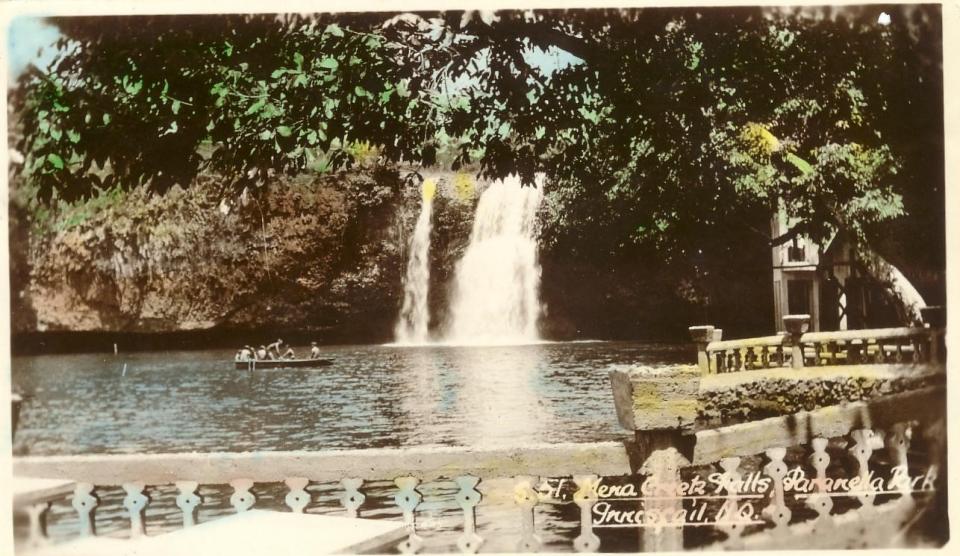

Paronella Park.

Paronella Park.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Paronella Park Photograph Collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Paronella was born in La Vall de Santa Creu in Catalonia, Spain and migrated to Australia in 1913. He initially found work as a sugar canecutter and saved money to buy a rundown farm. He improved it and sold it for a profit: a pattern he repeated many times. By 1924 he was wealthy, and when he purchased 12 acres of land surrounding Mena Creek Falls, he sought to realize his dream of building a castle reminiscent of his homeland.

Flooding and destruction at Paronella Park. Photograph possibly taken during the 1946 flood.

Flooding and destruction at Paronella Park. Photograph possibly taken during the 1946 flood.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Paronella Park Photograph Collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Now married, he first built a home, then began work on his castle. In Spain, the imprint of 800 years of Muslim rule was reflected in the Moorish architectural style of the buildings of the wealthy and powerful. Paronella replicated that style. Opened in 1935, the park facilities included a movie theatre, a ballroom, an ice-cream parlor, a café, a tunnel of love, waterfalls, picnic areas, tennis and bocce courts, and a swimming and boating pool replete with dressing rooms, a diving board, and small boats. He reforested the park and harnessed water from the falls to produce electricity with a hydro-electric plant, enabling the falls to be illuminated at night. Paronella Park became renowned throughout Queensland as a “magnificent Pleasure Resort.”

When, on 9 February 1946, the floodwaters rose and the park became isolated, Paronella was not alarmed. These were usual wet-season events. It was only when a neighbor warned him of water-borne logs heading towards the railway bridge upstream from Paronella Park that the full threat became apparent.

As the logs floated downstream they jammed against the bridge, creating a dam. The falls slowed to a trickle and then stopped. Soon the eerie, unaccustomed silence was broken by the roar of the rupturing bridge. Unable to withstand the pressure of the building pool of water and debris, the bridge gave way and unleashed a wall of water and massive cedar logs. Paronella and his family retreated to higher ground as logs smashed through walls. Steel girders were snapped, masonry features uprooted, and concrete balustrades dislodged. Gardens were destroyed. Yet six months and £8,000 later, the Park reopened.

Photograph of destruction caused by cyclone and flood destruction, possibly taken in 1946.

Photograph of destruction caused by cyclone and flood destruction, possibly taken in 1946.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Paronella Park Photograph Collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 1948 Paronella died, leaving his dream to be continued by his family. When fire destroyed the ballroom in 1979, the Park was abandoned as a “Pleasure Resort.” The rainforest grew back only to be shredded and uprooted by Cyclone Winifred in 1986. New owners purchased Paronella Park in 1993, determined to restore it as a tourist attraction, albeit as a ruined castle. Its location in tropical Queensland has led to repeated encounters with devastating cyclones, particularly Larry in 2006 and Yasi in 2011. Annual floods turn the falls into a frothing force that unleashes a turbulent muddy river of water and debris that batter remaining structures. Each time, the Park is closed, the damage assessed, repairs made, and the Park reopened with renewed optimism. That optimism is tempered by a growing understanding of how the effects of climate change may impact on the weather patterns at Mena Creek, and that restoration of the site’s built heritage is ultimately impossible.

Photograph of yet another flood at Paronella Park, this one after 1988.

Photograph of yet another flood at Paronella Park, this one after 1988.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of Paronella Park Photograph Collection.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Paronella Park is a remarkable example of human determination in the face of natural and human-made disaster. A Moorish castle, located in the Australian wet tropics, it is an edifice associated with a very different environment. The resilience of its original creator saw it restored after the catastrophic events of 1946. While that disaster was notable for the way in which logging exacerbated natural flooding, cyclones are a common event in tropical Queensland, and at Mena Creek they cause destructive floods. Paronella Park’s continuing presence in the landscape is a testament to the persistence of human dreams in the face of repeated environmental destruction.

How to cite

Balanzategui, Bianka Vidonja. “The Day the Falls Stopped Flowing: Devastation and Resilience in Tropical Queensland.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9001.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Bianka Vidonja Balanzategui

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Brannigan, Ed. “Paronella Park: A Magnificent Obsession.” Australian Garden History 10, no. 1 (1998): 20–21.

- Jones, Dorothy. Hurricane Lamps and Blue Umbrellas: A History of the Shire of Johnstone to 1973. Cairns: Bolton Press, 1973.

- Jones, S. A. “Castle Dreaming: Love in Paronella Park.” Kill Your Darlings 16, December 2013, 93–104.

- Leighton, Dena. The Spanish Dreamer: A Biography of José Paronella. Wollongong: Rosemont Press, 1997.

- Miles, Jinx. “Paronella Park: Conserving a Tropical Pleasure Garden with Ruined Concrete Structures.” Queensland Review 10, no. 2 (2003): 99–108.

- Mitchell, Annie. “Paronella Park: Music, Migration and the ‘Tropical Exotic.’” eTropic 12, no. 2 (2013): 197–209.

- Vader, John. Red Cedar: The Tree of Australia’s History. Frenchs Forest: Reed Books Pty Ltd., 1987.