A public artwork showing The Herbert River Farmers’ Association Meeting on a moonlit night.

A public artwork showing The Herbert River Farmers’ Association Meeting on a moonlit night.

Photograph by Bianka Vidonja Balanzategui.

Mosaic Installation Panel, Mercer Lane, Ingham.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In the Herbert River Valley in tropical north Queensland, independent, small, sugar cane farmers transformed their environment in a way few other small farmers in the global sugar world did. Traditionally this has been attributed to a collusion of state will and planter acquiescence in response to external forces. However, there are two additional significant factors: planter associational apathy and a critical mass of selectors who had the acumen, persistence, and freedom to form associations. They used those to investigate ways they could cultivate sugar in order to share the benefits of an industry then dominated by plantation concerns. A particular regional example of small farmers’ agricultural associations was the Herbert River Farmers’ Association (HRFA).

Plantation agriculture dominated the Herbert River Valley from 1872 to 1908. The vanguard of European settlers arrived in the Valley in 1868 and by 1872, when the first plantation mill commenced crushing, the plains of long grasses and forested areas of the Bandyin, Njawaygi, and Wargamay peoples’ traditional lands were being cleared for plantation agriculture. The planters held onto large tracts of unused land and invested heavily in milling, but often failed to use sound cultivation techniques. The wrath of the displaced Indigenous peoples, an inhospitable nature and the dangers of the environs, the mortality rate, the lack of services, and the caprices of the sugar industry all challenged the planters’ enterprises. Nevertheless, they failed to form a viable planters’ association to face the challenges with a united front.

Meanwhile, small selectors—a significant group of Scandinavians and those of Anglo-Celtic origins—were also attracted to the Herbert when government legislated for land ownership by a yeomanry class of white agriculturalists in order to stimulate agricultural production and to promote settlement for the defense of what was regarded as a tropical outpost. The small selectors farmed small crops and planted fruit trees. They kept pigs and fowls and both beef and dairy cattle. They supplemented their farm income with outside work such as fencing and building, timber getting, and pit sawing. By these means, they subsisted while supplying both the large sugar plantations and the wider community as it developed.

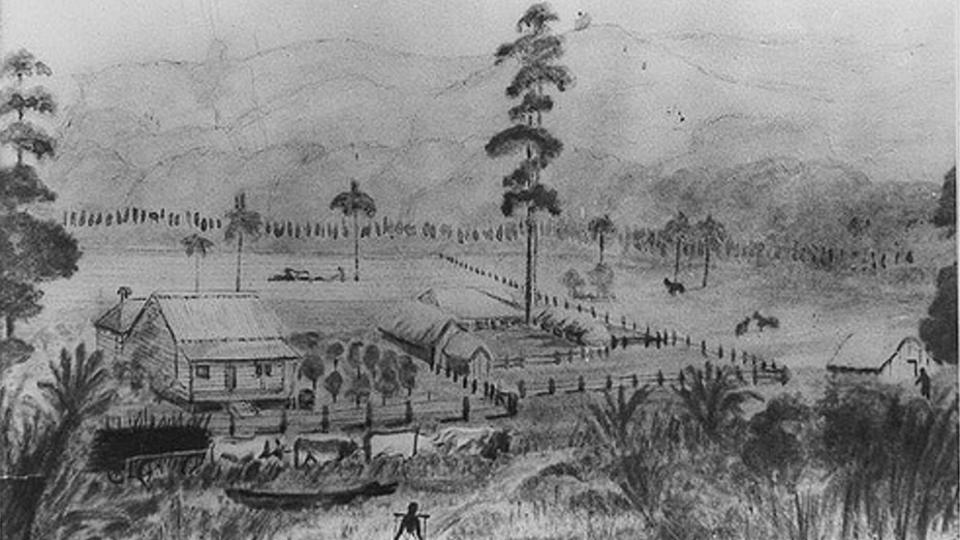

Samuel Griffith on an electioneering tour to the Herbert. Pictured with local landowners and businessmen, 1883. Griffith was Premier of Queensland from 1883 to 1888 and again from 1890 to 1893. When he became Premier in 1883 he replaced Premier Thomas McIllwraith. This was a blow to the planters because McIllwraith favored the importation of colored labor while Griffith opposed it.

Samuel Griffith on an electioneering tour to the Herbert. Pictured with local landowners and businessmen, 1883. Griffith was Premier of Queensland from 1883 to 1888 and again from 1890 to 1893. When he became Premier in 1883 he replaced Premier Thomas McIllwraith. This was a blow to the planters because McIllwraith favored the importation of colored labor while Griffith opposed it.

Courtesy of Hinchinbrook Shire Council Library Photographic Collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Government design was matched by those small selectors’ desire and capital to purchase land in order to secure their independence. Finding it difficult to make a living from small crops, because of the tropical climate, distance from markets and absence of transport facilities they looked to sugar. This was despite sugar being grown on plantations elsewhere in the tropical world and where, if there were small farmers, they grew sugar on small plots of planters’ land. Those small farmers’ situation was closely aligned with that of plantation workers and was not one Queensland’s settlers aspired to. White, independent, small sugar cane farmers were rare. Sugar, despite being labor intensive, offered the best opportunity for the small growers because they did not have to personally worry about milling, transporting, or marketing the crops, and there was the possibility of using non-white labor during the harvest.

Photograph of Scandinavian small farmer N. C. Rosendahl with his family, Halifax, 1914.

Photograph of Scandinavian small farmer N. C. Rosendahl with his family, Halifax, 1914.

Originally published in Northern Herald, 2 October 1914, 26.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 1881, a delegation of small selectors approached the Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR) to suggest that they grow sugar cane for milling at its Victoria Mill. This approach was audacious given the reputation and size of that Company (it had interests in not only sugar cultivation, but milling and refining). It is unclear whether the farmers anticipated success. The Company made it quite clear it would be growing its own cane for its mill and was unwilling to talk with a small farmer delegation unless it was making a collective approach with a guaranteed tonnage of cane supply. As a result, the selectors formed an association, the HRFA, and approached CSR again. In 1881, in sugar growing areas, agricultural associations were the prerogative of planters. But agricultural associations were a worldwide phenomenon and in temperate areas, growers of small crops did form them. They were a proven effective vehicle for accessing education to improve agricultural practices, promoting agricultural skills and innovation and for political lobbying. Despite being generally dismissed, small farmers’ associations in Australia were an important intermediate stage between “individual innovative effort” and “centralized agricultural research.” On the Herbert, the Scandinavians brought to the HRFA their home country “collaborative traditions,” as did the Anglo-Celtic immigrants from farming backgrounds. In 1884, CSR offered the HRFA farmers firm contracts. CSR already crushed cane provided by the small farmers who grew it along the coastal rivers of sub-tropical northern New South Wales (NSW). The agreement CSR made with the HRFA in 1884 was modeled on that already in practice in NSW. The HRFA farmers went on to disprove the perception that independent, white, small farmers could neither physically farm sugar in a tropical environment nor provide a reliable supply of high-quality cane. The same outcome was not achieved in sugar industries elsewhere in the world. Farmers in the Herbert Valley used the HRFA to negotiate pricing with CSR, lobby government, obtain suitable cane varieties, and source and share information on sound cultivation techniques.

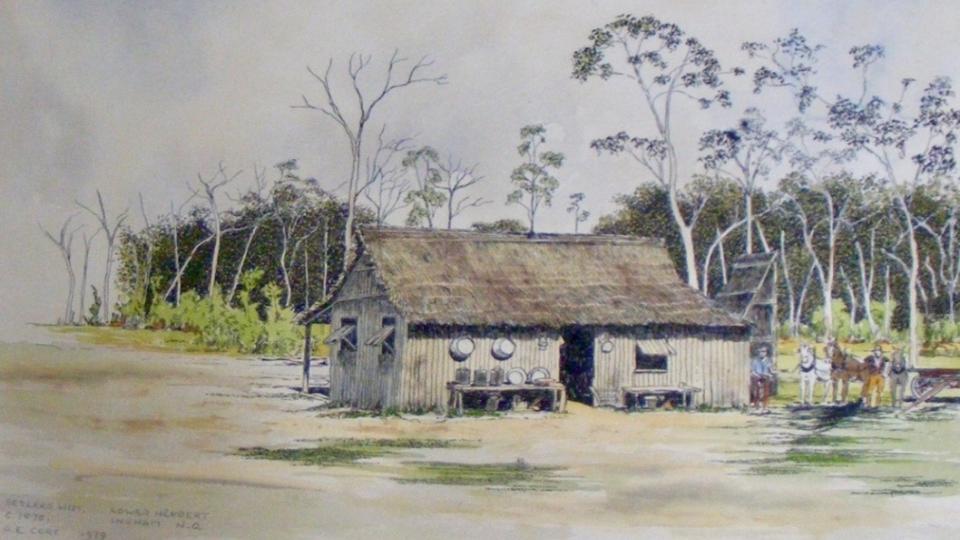

Drawing of Arthur W. Carr’s small farm, Oakleigh, Cordelia Vale. The cottage was a former Gairloch Plantation cottage, circa 1878–1899.

Drawing of Arthur W. Carr’s small farm, Oakleigh, Cordelia Vale. The cottage was a former Gairloch Plantation cottage, circa 1878–1899.

Courtesy of Carr family, Cordelia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The HRFA was the cornerstone of the institutional foundations of a unique industry. It encouraged farmers to be knowledgeable and progressive agriculturalists and unified in order to realize common goals. It enabled the small farmers to be provocateurs and agents of change transforming the Australian sugar industry from plantations to small family farms and propelling it into global prominence, enjoying a level of protection and subsidization enjoyed by few other sugar industries.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was conducted by using material from State Archives Brisbane Queensland, State Library Brisbane Queensland, National Library Canberra ACT, CSR Archives Noel Butlin Archives ANU Canberra ACT, Special Collections JCU Townsville Queensland, and Hinchinbrook Shire Council Library Local History Collection Ingham, Queensland.

How to cite

Balanzategui, Bianka Vidonja. “Small Farmers, Their Association, and the Transformation of the Australian Sugar Industry.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2019), no. 26. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8746.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Bianka Vidonja Balanzategui

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

Graves, Adrian, A. Cane and Labour: The Political Economy of the Queensland Sugar Industry, 1862-1906. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993.

Griggs, Peter. “The origins and early development of the small cane farming system in Queensland, 1870–1915.” Journal of Historical Geography 23 (1997): 46–61.

Griggs, Peter. “Sugar Plantations in Queensland, 1864-1912: Origins, Characteristics, Distribution, and Decline.” Agricultural History 74 (2000): 609-47.

- Lund, Fredrik Larsen. “A Norwegian Waltz: Norwegian Immigration and Settlement in Queensland 1879-1914.” Masters diss., University of Oslo, 2012.

- Moore, Clive. “The Transformation of the Mackay Sugar Industry, 1883-1900.” B. Arts Hons. diss., James Cook University, 1974.

Raby, Geoff. Making Rural Australia: an economic history of technical and institutional creativity, 1788-1860. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Shogren, Diane. “The Queensland Sugar Industry to 1930.” PhD diss., University of Queensland, 1980.