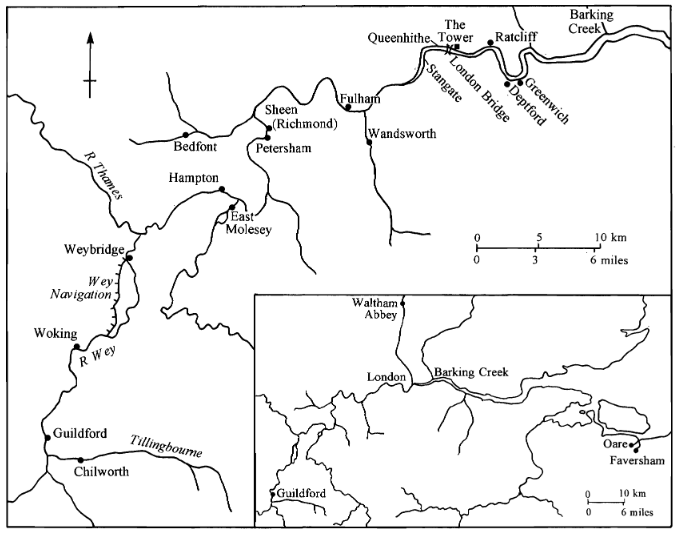

The River Tillingbourne (bottom left, main map) flows west into the River Wey to the south of Guildford. The Chilworth gunpowder works remained the most important production site in England until they were outperformed by the Royal Gunpowder Mills at Waltham Abbey (top of inset) in the Lea Valley.

The River Tillingbourne (bottom left, main map) flows west into the River Wey to the south of Guildford. The Chilworth gunpowder works remained the most important production site in England until they were outperformed by the Royal Gunpowder Mills at Waltham Abbey (top of inset) in the Lea Valley.

Courtesy of Surrey Archaelogical Collections and the Archaeology Data Service.

Originally published in K. R. Fairclough, “Thomas Coram: His Brief Period as a Gundpowder Producer,”

Surrey Archaeological Collections 86, 53–72 (1999): 58.

© F. R. Fairclough. Map reused under the Archaeology Data Service’s terms of use. Click here to see terms.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The River Tillingbourne rises in the county of Surrey on Leith Hill, the second highest vantage point in southeast England. After 24 kilometers, the stream joins the River Wey, a tributary of the Thames. Since at least the Norman Conquest, the Tillingbourne has powered numerous mills that were initially used for processing commodities such as grain and wool. In September 1626 the East India Company received permission from the owner of a site in Chilworth, about three kilometers southeast of Guildford, to develop gunpowder manufacturing facilities, after initial operations in Thorpe were said to disrupt the feeding patterns of the king’s deer.

The same year, the company that historian Nick Robins describes as “the mother of the modern multinational” imported its first load of saltpeter from the Coromandel Coast of eastern India. It was at this point that the development of the site’s landscape and industrial heritage started to merge with histories of colonialism and overseas resource extraction. This in turn prepared the way for the gradual transfer of technologies that would accompany the emergence of the European arms race towards the end of the nineteenth century.

The site of the gunpowder mills of the 1620s would have been to the left of this culvert (which flows west, out of the site that is now open to the public); to the right is the probable site of an earlier mill recorded in the Domesday Book.

The site of the gunpowder mills of the 1620s would have been to the left of this culvert (which flows west, out of the site that is now open to the public); to the right is the probable site of an earlier mill recorded in the Domesday Book.

Photograph by Ben Tendler.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

As England prepared for the Anglo-Spanish War (1625–1630), shortages of saltpeter and gunpowder arose. Thus the East India Company attempted to secure a reliable supply of gunpowder for its own private use—including in clashes with the Dutch and the Portuguese, its principal rivals during the spice race in South and Southeast Asia—at a reasonable cost. This had to be achieved without provoking undue opposition from the king and from the Evelyn family, who enjoyed a monopoly on saltpeter produced in England as the Crown’s sole gunpowder supplier.

The quality of the saltpeter from eastern India was superior to that of European origin. Whereas sulfur was often imported too (from volcanic regions such as Sicily), Surrey’s charcoal producers provided the other key ingredient. Thus the scene was set for the relatively peaceful watercourses between Chilworth and the Thames steadily to become a transport route for explosives.

However, production in Chilworth proved precarious, owing to managerial disputes and the quality of the end product, not to mention a minor explosion in May 1628. That year the Company subcontracted out gunpowder production at the mills. In 1629 Charles I dissolved parliament, a move that left him in need of alternative sources of income to the taxes that parliament normally granted. After the king tightened his control of the industry, the Company lost its right to produce gunpowder at the mills in 1632 and relinquished all ties to the site in 1636. The works then supplied the parliamentary side during the Civil War (1642–1651) when not being raided by Royalists. During the course of the century, it became the largest and most important gunpowder production site on the Atlantic Archipelago.

Walking eastwards through the site, one encounters these millstones (“edge runner stones”), which were stood on their sides to provide protection in the event of accidental blasts at a later stage of the site’s development. Today, they are one of the works’ most iconic features.

Walking eastwards through the site, one encounters these millstones (“edge runner stones”), which were stood on their sides to provide protection in the event of accidental blasts at a later stage of the site’s development. Today, they are one of the works’ most iconic features.

Photograph by Ben Tendler.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most gunpowder was used for military purposes, but also for hunting and for blasting in mines and quarries. As demand for gunpowder in overseas trade grew, some entered the triangular trade in which “merchants’ powder” featured among the commodities exchanged for slaves in West Africa, who were then shipped across the Atlantic (Crocker and Crocker 2000, 50–52; Cocroft 2000, 16). Tobacco and sugar from the slave plantations would then be distributed to ports in London, Liverpool, and Bristol.

The Chilworth gunpowder works finally closed in 1920 due to industry consolidation, caused not least by overcapacity after World War I. Many of the buildings were fired, then standard practice for the decontamination of explosives buildings. The site is now protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979, the latest in a series of legislation stretching back to the Ancient Monument Protection Act of 1882, which was introduced to protect sites such as the Avebury stone circles.

Continuing eastwards, the walker encounters the remains of the incorporating mills of the 1880s and the Charge House (left), built alongside the “New Cut” of the 1650s (right), one of several channels drawn off from the Tillingbourne.

Continuing eastwards, the walker encounters the remains of the incorporating mills of the 1880s and the Charge House (left), built alongside the “New Cut” of the 1650s (right), one of several channels drawn off from the Tillingbourne.

Photograph by Ben Tendler.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Efforts to conserve and research the works, which stretch for approximately 1.5 km along the Tillingbourne, have since won increasing public recognition, receiving the Surrey Industrial History Group’s conservation award in 2010 and national funding in 2015 from what is now the National Lottery Heritage Fund. This funding resulted from a joint application by the local community and the body responsible for managing the Surrey Hills area, which in 1958 was one of the first to be designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The funding enabled the creation of Tillingbourne Tales, a research project with some online presence that brought together communities in the valley to promote heritage trails and capture local knowledge in oral histories and a local museum exhibition.

Around four centuries after gunpowder production commenced on the Tillingbourne, nature has returned. The site, densely wooded in parts, is now a haven for protected species such as dormice and bats (Pipistrelle, Netterers, Brown Long-Eared). However, new challenges include ash dieback and phosphate enrichment of the Tillingbourne. As the conservation of the site passes on to the next generation, local communities continue to play an active role. Meanwhile, the place still faintly tingles with the “dangerous energy” that archaeologist Wayne D. Cocroft documents in his English Heritage history of the explosives industry.

Acknowledgments

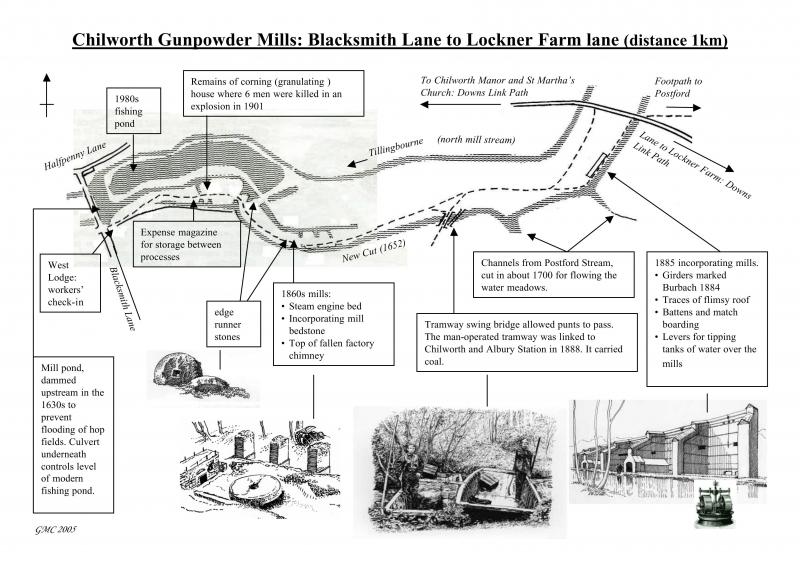

This text was made possible by a moment of calm during an Anthroposcenic safari along another stretch of water altered by human technologies, namely the meander in the Haselbach created under the stewardship of Joachim Strobel, head of nature and landscape at Stiftung Nantesbuch, Bad Heilbrunn. The map of the Chilworth Gunpowder Mills (right) is used here with the kind permission of Glenys Crocker, the map’s creator.

For the source of the phrase “Commonwealth of Powder-makers” in the title of this Arcadia entry, see John Aubrey, The Natural History and Antiquities of the County of Surrey vol IV (London: E. Curll, 1718): 56; also quoted by the Crockers, p.23.

How to cite

Tendler, Ben. “From ‘Commonwealth of Powder-makers’ to Haven for Protected Species: The Chilworth Gunpowder Works.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2021), no. 25. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9338.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Ben Tendler

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Crocker, Glenys, and Alan Crocker. Damnable Inventions: Chilworth Gunpowder and the Paper Mills of the Tillingbourne. Guildford: Surrey Industrial History Group, 2000. See p. 23 for the reference to “a little Commonwealth of Powder-makers,” a description of Chilworth and its gunpowder mills by English antiquary John Aubrey (1626–1697).

- Fairclough, K. R. “The East India Company and gunpowder production in England, 1625–1636.” Surrey Archaeological Collections 87 (2000): 95–111.

- Fairclough, K. R. “Thomas Coram: His Brief Period as a Gunpowder Producer.” Surrey Archaeological Collections 86 (1999): 53–72.

- Cocroft, Wayne D. “Chilworth Gunpowder Works, Chilworth: Survey Report,” Archaeological Investigation Report Series AI/20/2003. Swindon: National Monuments Record Centre (English Heritage), 2003. (Link)

- Cocroft, Wayne D., and Catherine Tuck, with contributions by Jonathan Clarke and Joanna Smith. “The Development of the Chilworth Gunpowder Works, Surrey, from the Mid-19th Century.” Industrial Archaeology Review 27 (2005): 217–234.

- Cocroft, Wayne D. Dangerous Energy: The Archaeology of Gunpowder and Military Explosives Manufacture. Swindon: English Heritage, 2000.

- Robins, Nick, The Corporation That Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational. London: Pluto, 2012.