Although published on 14 May 1887, the descriptions of wildfires contained in the newspaper would not surprise the twenty-first-century reader: a reporter describing how “huge flames can be seen … lighting up the sky,” while “dense clouds of smoke” ensconce neighboring towns in a caustic haze, evokes the contemporary megafires (i.e., large fires burning with extremely high severity and/or intensity) that are presently a constant headline across the western United States, Australia, the Mediterranean, and other fire-prone regions. However, this report was published in the Boston Daily Globe and concerned wildfires in a place better known for its beaches than its blazes—scenic Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Remembering the seemingly forgotten fires of 1887 should remind a region that considers itself ostensibly insulated from wildfires that fire was—and may yet again be—a socially and ecologically influential force.

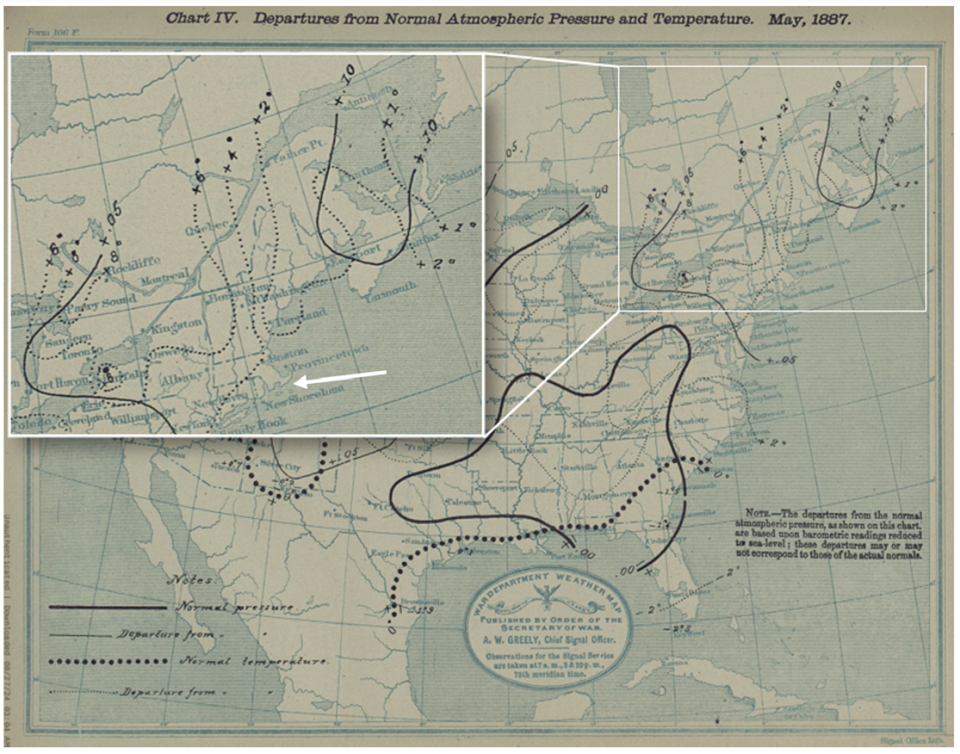

Map from 1887 depicting abnormally high atmospheric pressure and warm temperatures—factors that promote wildfire activity. Small, dotted lines delineate areas of greater temperature, and solid non-bold lines delineate areas of greater atmospheric pressure, relative to climatic normals. The Cape (indicated by an arrow) was experiencing atmospheric pressures well above normal, and the highest pressure observed in the country during May was recorded near Falmouth (30.09 inHg).

Map from 1887 depicting abnormally high atmospheric pressure and warm temperatures—factors that promote wildfire activity. Small, dotted lines delineate areas of greater temperature, and solid non-bold lines delineate areas of greater atmospheric pressure, relative to climatic normals. The Cape (indicated by an arrow) was experiencing atmospheric pressures well above normal, and the highest pressure observed in the country during May was recorded near Falmouth (30.09 inHg).

© National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The proximate cause of at least six distinct fires that erupted on 11 May 1887 was abnormally warm and dry weather. Records from the United States Signal Service for May indicate that the region received around 60% of expected rain and was around 4°F (c. 2.2°C) warmer than the monthly average for the period. However, the immediate cause of each individual fire varied: one was reportedly caused by “huckleberry parties” who were perhaps burning to promote a tasty fruit that is encouraged by fire—an ordinarily benign practice that could have led to large fires under dry conditions.

Regardless of origin, the fires elicited a community-wide response. With limited access to steam fire engines, locals fought the fire with shovels and whatever other equipment they could acquire. They also frequently lit “backfires”—burns intentionally set in advance of an approaching wildfire to consume fuel and slow the wildfire’s advance. This action likely saved the village of Bourne from destruction. However, despite heroic efforts, the fire spread 20 US miles (c. 32 kilometers) to the south and threatened the town of Falmouth. By the next day, the fires had yet to be contained and over 50,000 acres had burned.

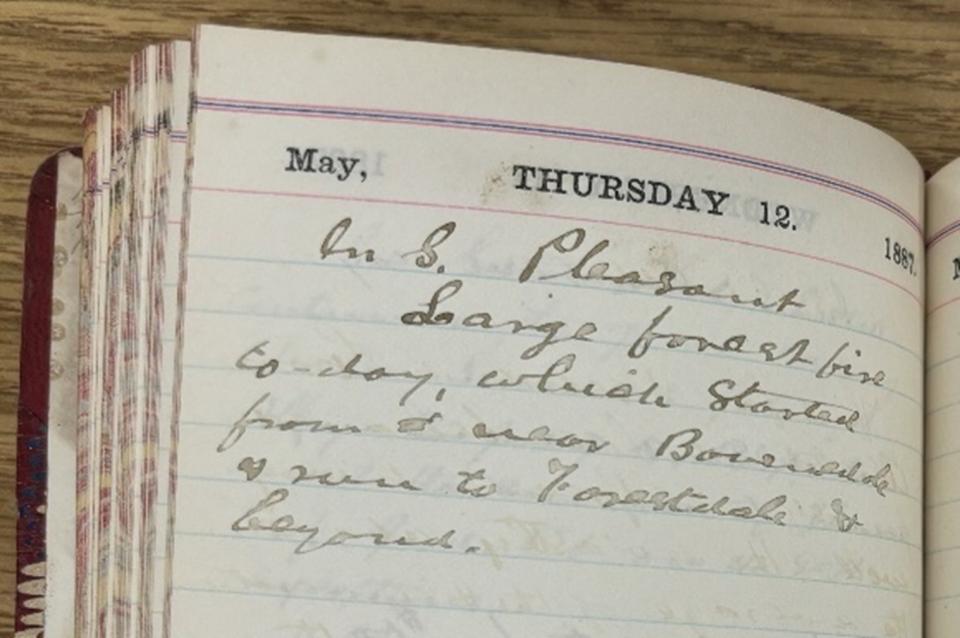

An excerpt from the diary of a local official, Ebenezer S. Whittemore, referencing the blazes. He notes that were was a “large forest fire to-day, which started from near Bournedale” and then exploded “to Forestdale & beyond.” Future residents of the region would go on to experience other large fires, perhaps most notably a blaze in 1938 that killed three firefighters. The region was also rocked by fire in 1957 and 1963.

An excerpt from the diary of a local official, Ebenezer S. Whittemore, referencing the blazes. He notes that were was a “large forest fire to-day, which started from near Bournedale” and then exploded “to Forestdale & beyond.” Future residents of the region would go on to experience other large fires, perhaps most notably a blaze in 1938 that killed three firefighters. The region was also rocked by fire in 1957 and 1963.

© Sturgis Library, Barnstable, MA, United States.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Only with the help of over 1,000 men were the fires largely extinguished by the next day (13 May). In total, over 75,000 acres burned and thousands of dollars in property damages accrued. Although no lives were lost, the Boston Daily Globe later described the fires as “the most disastrous in the memory of man.” This statement is made more remarkable given that the 1887 Cape Cod fires were part of a broader collection of wildfires that erupted across the northeastern and midwestern United States during the late nineteenth century. For these burns to stand out in an era marked by wildfires illustrates their cultural impact. Additionally, the close proximity of these fires (around 50 US miles or 80 kilometers) to a major metropolitan center, Boston, likely amplified their cultural resonance. However, descriptions of the fires as being almost apocalyptic must be tempered by the recognition that what was bad for people is not necessarily ecologically disastrous.

A prescribed burn on Cape Cod in 2019. This fire was set in an ecosystem compositionally similar to the woods that burned in 1887. Both dominated by the fire-dependent pitch pine—a tree that only successfully establishes after disturbance and can survive fire with its thick bark—and that actually encourages fire with is flammable sap. Other common species include huckleberry and blueberry—species that can resprout after fire because of their extensive network of below-ground stems. Without disturbance like fire, these species are often outcompeted by more shade-tolerant species.

A prescribed burn on Cape Cod in 2019. This fire was set in an ecosystem compositionally similar to the woods that burned in 1887. Both dominated by the fire-dependent pitch pine—a tree that only successfully establishes after disturbance and can survive fire with its thick bark—and that actually encourages fire with is flammable sap. Other common species include huckleberry and blueberry—species that can resprout after fire because of their extensive network of below-ground stems. Without disturbance like fire, these species are often outcompeted by more shade-tolerant species.

2019 Sam Gilvarg

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Despite the evident contemporary impact of these fires, memory of the event has largely been extinguished today—something emblematic of widespread disregard of fire’s historical and ecological role in the region. A quiescence of fire beginning in the early twentieth century has likely contributed to the belief that fire did not have a substantial influence here: however, this recent absence is actually an outlier that stands in stark contrast to the Cape’s fiery past. Analyzed patterns in fire scars within tree-ring chronologies, charcoal or pollen deposition across sediment cores, local Indigenous knowledge, and fire-adaptive traits exhibited by once common plant and wildlife species all demonstrate a non-ignorable influence of fire on regional forest development. Historian Stephen Pyne notes how the Cape is “among the most flammable landscapes in America” because of its vegetation and refers to Cape Cod as “Cape Flame.” Written accounts by early colonists further attest to this, noting Indigenous peoples’ use of fire to attract game, promote desirable plants, and clear travel routes. Early European settlers continued to use fire management for agriculture until widespread agricultural abandonment in the nineteenth century.

This photo depicts land managers burning an overgrown forest on Cape Cod—efforts that have increased in recent years. Actively using fire and fire-surrogates (mechanical treatments like forest thinning) offers a means to build a more fire-resilient landscape on Cape Cod. Trained professionals conduct these practices to realize a range of socioecological objectives, including a reduction in the risk of large wildfires and the promotion of rare plants.

This photo depicts land managers burning an overgrown forest on Cape Cod—efforts that have increased in recent years. Actively using fire and fire-surrogates (mechanical treatments like forest thinning) offers a means to build a more fire-resilient landscape on Cape Cod. Trained professionals conduct these practices to realize a range of socioecological objectives, including a reduction in the risk of large wildfires and the promotion of rare plants.

© Hunter Moore/UNH

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Forgetting wildland fire’s regional legacy led to the idea that it could be completely excluded, and governmental agencies nearly did just that in the early twentieth century (i.e., the “Smokey Bear” era) but not without catalyzing widespread ecological change and future challenges. Alongside driving declines in disturbance-dependent biodiversity, fire’s removal has promoted forests densely packed with flammable vegetation—leaving the region inherently more susceptible to wildfires of ahistoric severity. This risk will only increase: climate change will likely substantially increase regional fire activity. As such, managing the Cape for blazes in addition to beaches should be a priority. The extremely active recent fire season of Fall 2024 relative to recent baselines illustrates this risk.

Using prescribed fire to moderate the risk of wildfires threatening people while simultaneously promoting biodiverse and resilient ecosystems offers a different path forward. Prescribed fire is the application of fire under predetermined weather and forest conditions to accomplish specific management objectives. It can be employed to address hazardous fuel loads and declines safely and effectively in disturbance-dependent biota. The 1887 fires illustrate the potential for the Cape’s forests to burn and should spur stakeholders to prophylactically manage the landscape accordingly. Moreover, the lesson learned here can be applied to other regions that have experienced recent fire deficits. Mining the historical record for clues regarding where such fires could rekindle may thus prevent future human tragedy.

How to cite

Gilvarg, Samuel C., and Andrew L. Vander Yacht. “Beaches to Blazes: Remembering the 1887 Cape Cod Wildfires Ahead of a Potentially Fiery Future” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2026), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/10072/

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2026 Samuel C. Gilvarg and Andrew L. Vander Yacht

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- “Forest Fires Raging: Southern Plymouth and Northern Barnstable County Towns Greatly Damaged — Loss Estimated at $50,000.” Boston Daily Globe, 13 May 1887, p. 2. Accessed via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Gao, Peng, Adam J. Terando, John A. Kupfer, J. Morgan Varner, Michael C. Stambaugh, Ting L. Lei, and J. Kevin Hiers. “Robust Projections of Future Fire Probability for the Conterminous United States.” Science of The Total Environment 789 (October 1, 2021): 147872. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147872.

- “Heaven-Kissing Flames: Light Up the Sky Over All Cape Cod — Narrow Escape of Many Towns in the Vicinity of Wareham — Forest Fires and Small Blazes all Over New England.” Boston Daily Globe, 14 May 1887, p. 2. Accessed via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Patterson III, William, and Kenneth Sassaman. “Indian Fires in the Prehistory of New England.” In Holocene Human Ecology in Northeastern North America, edited by George Nicholas. Plenum Press, 1988.

- Pyne, Stephen J. The Northeast: A Fire Survey. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2019.

- United States Signal Service. “May, 1887.” Monthly Weather Review 15, no. 5 (1887): 127–53.

- Vander Yacht, Andrew L., Samuel C. Gilvarg, J. Morgan Varner, and Michael C. Stambaugh. “Future Increases in Fire Should Inform Present Management of Fire-Infrequent Forests: A Post-Smoke Critique of ‘Asbestos’ Paradigms in the Northeastern USA and Beyond.” Biological Conservation 296 (August 2024): 110703. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110703.