A Great Land Waiting

“Rockies Scene, 1920.” A photograph from one of MB’s 1920s research trips in the Rocky Mountains.

“Rockies Scene, 1920.” A photograph from one of MB’s 1920s research trips in the Rocky Mountains.

Courtesy of Sylvia Watson.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

If in 1920 you were looking for someone to introduce readers to the national parks of Canada’s Rocky Mountains, MB Williams would seem the unlikeliest of candidates. She had passed her fortieth birthday without ever visiting Western Canada, let alone its national parks, and was not in the least bit outdoorsy. She also suffered from a poorly understood form of anemia, which periodically kept her bedridden for weeks or months at a time. Despite all this, Commissioner Harkin sent her out west to explore and write about the parks.

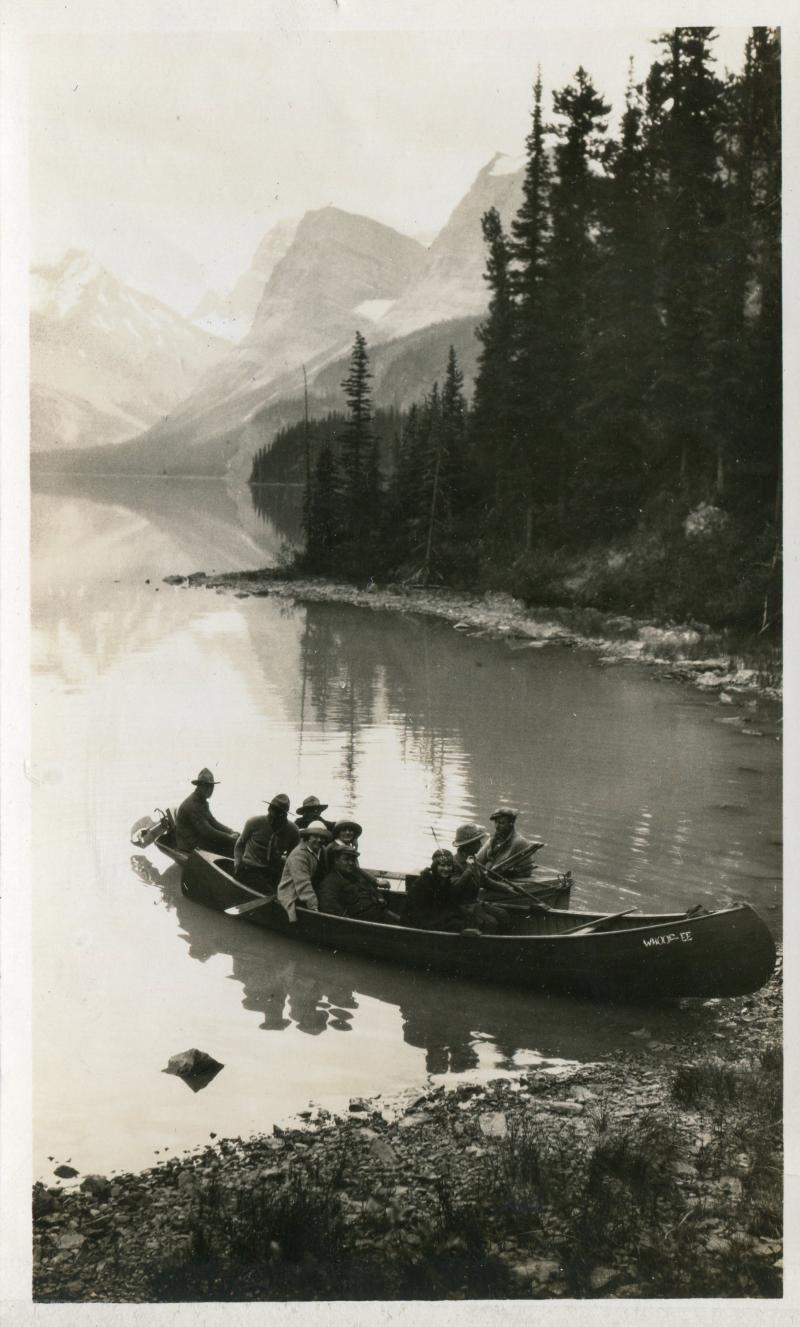

MB would later tell her niece Frances Girling that at the end of her first day horseback riding through Jasper National Park, she got off the horse and fainted. But when Girling herself took a train through the Rockies, the conductor regaled her with stories about a woman from Ottawa—MB—who, having never been on a horse before, rode the length and breadth of the mountain parks. In the few surviving photographs of MB’s 1920s research trips—shots of canoeing, picnicking, and relaxing at Jasper Lodge—she certainly seems to be enjoying herself.

MB Williams picnicking during a research trip in the Rockies in the 1920s

MB Williams picnicking during a research trip in the Rockies in the 1920s

Photograph courtesy of Sylvia Watson, grandniece of MB Williams.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

MB (seated, in white), J. B. Harkin (seated at right, under lamppost), and others gather at Jasper Lodge in August 1923.

MB (seated, in white), J. B. Harkin (seated at right, under lamppost), and others gather at Jasper Lodge in August 1923.

Photograph courtesy of Sylvia Watson, grandniece of MB Williams.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

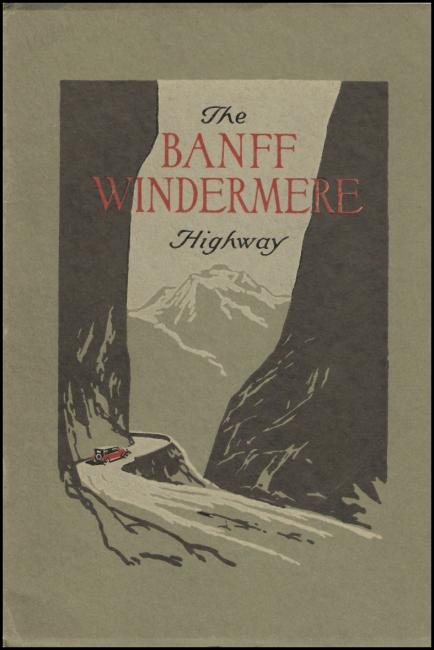

Williams’s timing in becoming an author of park guidebooks was impeccable. The early 1920s saw the rise of auto tourism and the parallel rise of government expenditure on tourism promotion. MB’s first guidebook, the 1921 Through the Heart of the Rockies and Selkirks, was the Branch’s first mass-market one, available to whoever wanted a copy. Approximately 100,000 copies of the book were printed in its first half-dozen years. It led to the equally successful 1923 The Banff-Windermere Highway, created for the road’s opening, and from there over the rest of the decade to Waterton Lakes National Park, Kootenay National Park and the Banff-Windermere Highway, Jasper National Park, Prince Albert National Park, Jasper Trails, and The Kicking Horse Trail. They are the most comprehensive and highest quality series of guidebooks that Parks Canada ever produced.

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing the series of guidebooks.

The Banff-Windermere Highway, 1924

A compact, beautifully-photographed guide to the new highway that vastly improved automobile travel in the Rocky Mountain parks.

Read the book here.

Waterton Lakes Park, 1927?

Focusing on the southern Alberta park that shares a border with Montana’s Glacier National Park, this travel guide is from around 1927.

Read the book here.

Jasper National Park, 1928

At 176 pages, this is really more of a book than a tourist guidebook; parks commissioner JB Harkin had to defend its size and expense to his superiors. In its production design and its detailed examination of Jasper past and present, it is one of the finest parks guidebooks of the 1920s.

Read the book here.

Prince Albert National Park, 1928

This 1928 guidebook about the Saskatchewan park includes a foreword credited to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King - but written by MB Williams. Her name would be removed entirely from the 1935 edition.

Read the book here.

Through the Heart of the Rockies & Selkirks, 1929 [1921]

The first guidebook under MB Williams’ name, the first Parks Branch one of the 1920s, and still one of the loveliest. This is the fourth edition of a guide first published in 1921.

Read the book here.

Jasper Trails, 1930?

This guidebook from around 1930 offers a more concise exploration of Jasper National Park.

Read the book here.

The Kicking Horse Trail, 1930 [1927]

The scenic trail between Lake Louise, Alberta and Golden, British Columbia is the jumping-off point for a fawning tribute to the automobile. This is the 1930 edition of a guidebook first published in 1927.

Read the book here.

Guardians of the Wild, 1936

The first history of Parks Canada and of the Canadian national parks system was written and published in Great Britain. Williams never mentions her own part in that history.

Read the book here.

The Banff Jasper Highway, 1963 [1948]

This is a 1963 edition of MB’s 1948 book, itself a close replica of her 1920s guides.

Read the book here.

MB’s guidebooks differ from the few previous examples of Canadian parks promotional guides. Her writing seeks a relaxed, literary effect. Chapters begin with a quotation, linking the parks to noted thinkers. Williams not only discusses the park’s history and traces an area-by-area excursion to sites of interest throughout it, but also takes time to express how parks, in general, fulfill important social, spiritual, and environmental goals: her guidebooks are as much an advertisement for parks in general as for the individual park.

But what strikes today’s reader the most is the sense that all of the park was opened up for the visitor, and for the reader. Perhaps that speaks to the time when MB was writing: it was after the automobile had made the entire park—the entire country, even—accessible to travelers, but before sufficient services and destinations had been established that regulated their travel. Or maybe it just speaks to MB’s skill as a writer. She would later use as an epigraph for Guardians of the Wild a quote by British socialist Edward Carpenter:

I see a great land waiting for its people to take possession of it.

The line could as easily describe how she promoted Canadian parks to tourists in the 1920s.

MB’s success writing travel guides changed her career, and her life. Whereas her salary had only risen from $1200 to $1300 in the 1910s, it jumped to $1560 the year she published Through the Heart of the Rockies and Selkirks, and to $2160 the next. Her job title shifted to “publicity assistant” and then “publicity agent.” She was soon overseeing much of the work in the Branch’s new Publicity Division, and when the agency started making travel and wildlife documentaries, she found she had a knack for matching pictures to prose, and penned the script for fifty films. But she never became “publicity director,” a position instead given to J. C. Campbell. A 1928 letter suggests a certain bitterness to him. She had risen farther and faster than almost all female government employees had, but she reached a ceiling.

When the Depression hit, many positions at the Parks Branch’s Ottawa office were lost. MB Williams’s job was likely safe, given both her seniority—she oversaw a considerable staff, including all of the women in the office—and the fact that she was good friends with Prime Minister R. B. Bennett’s family. But when her staff was laid off, she chose to join them. The year 1931 introduced a decade of great change for MB, just as 1911 and 1921 had.