Everything After

An illustration of prong-horned antelope in an article titled “National Parks and Sanctuaries in Canada” by M. B. Williams in The Animals’ Friend magazine, June 1936. Click here to read the article.

An illustration of prong-horned antelope in an article titled “National Parks and Sanctuaries in Canada” by M. B. Williams in The Animals’ Friend magazine, June 1936. Click here to read the article.

Illustrator unknown.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

MB’s involvement with Grey Owl’s lecture tour revived her interest in Canadian national parks, and she published a short article about them. It also got her talking to the London publishers Thomas Nelson & Sons, who were putting out a book on Grey Owl. Would they be interested in a book about Canada’s national parks? The publisher accepted in April 1936 and asked for the manuscript by June. MB fretted to A. B. Buckley that summer about writer’s block, but nonetheless in the space of just five months she wrote and saw to publication the first history of Canada’s national parks and its park service.

Guardians of the Wild opens with the rain beating down on an Ottawa office window in September 1911, and an unnamed “Commissioner”—who is presented as having the genius and far-sightedness of the Creator—contemplating the responsibility of having a 20,000-square-kilometer kingdom under his control, thousands of kilometers away. It goes on to describe how parks came about, what they do for people and for nature, and how much the Parks Branch had accomplished in its first quarter-century. And yet, Williams’s book never betrays her own role in the history of the park system. Guardians of the Wild earned good reviews, including a radio review transcript sent to her by Commissioner Harkin. Another reviewer noted that Harkin himself cited Williams as being “an inspiring and dominant factor in the works of the Parks Branch for some twenty years.” Williams received many notes of congratulation, including two from Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. In the second, he apologizes for taking a whole two weeks to reply personally to Williams’s letter, saying it “dropped out of sight at the time of ‘the constitutional crisis.’” This truly was a different era.

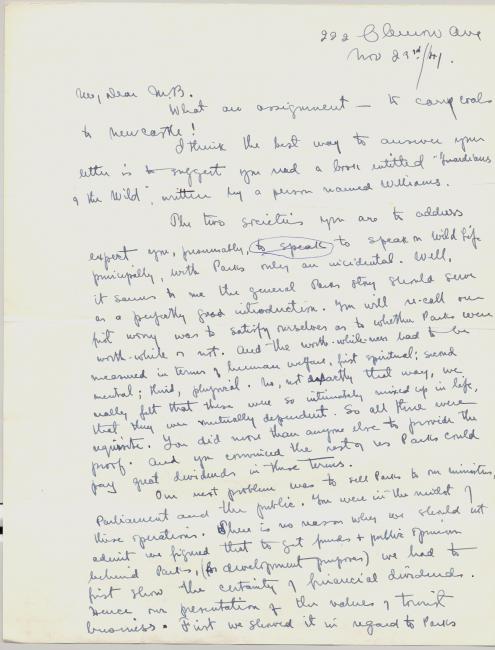

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document. It features a letter from J. B. Harkin to MB Williams from 23 November 1941.

Letter from J. B. Harkin to MB Williams, 23 November 1941

J. B. Harkin to MB Williams, 23 November 1941

222 Clemow Ave

Nov 23rd/41.

My Dear M. B.

What an assignment—to carry coals to Newcastle!

I think the best way to answer your letter is to suggest you read a book entitled “Guardians of the Wild”, written by a person named Williams.

The two societies you are to address expect you, presumably, to speak on wild life principally, with Parks only an incidental. Well, it seems to me the general Parks story should serve as a perfectly good introduction. You will re-call our first worry was to satisfy ourselves as to whether Parks were worth-while or not. And the worth-while-ness had to be measured in terms of human welfare, first spiritual; second mental; third, physical. No, not exactly the way, we really felt that these were so intimately mixed up in life, that they were mutually dependent. So all three were requisite. You did more than anyone else to provide the proof. And you convinced the rest of us Parks could pay great dividends in these terms.

Our next problem was to sell Parks to our ministers, Parliament and the public. You were in the midst of those operations. There is no reason why we should not admit we figured that to get funds & public opinion behind Parks, (for development purposes) we had to first show the certainty of financial dividends. Hence our presentation of the values of tourist business. First we showed it in regard to Parks

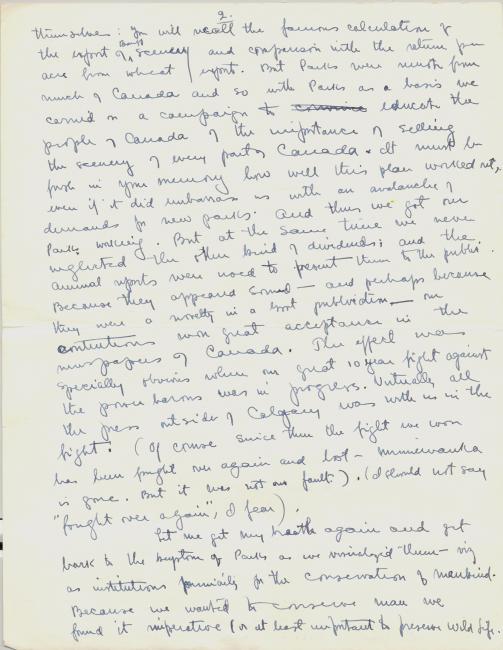

themselves: you will recall the famous calculation of the export of Banff scenery and comparison with the return per acre from wheat exports. But Parks were remote from much of Canada and so with Parks as a basis we carried on a campaign to educate the people of Canada of the importance of selling the scenery of every part of Canada. It must be fresh in your memory how well this plan worked out, even if it did embarrass us with an avalanche of demands for new parks. And then we got our Parks working. But at the same time we never neglected the other kind of dividends; and the annual reports were used to present them to the public. Because they appeared sound—and perhaps because they were a novelty in a Govt publication — our contributions won great acceptance in the newspapers of Canada. The effect was specially obvious when our great 10 year fight against the power barons was in progress. Virtually all the press outside of Calgary was with us in the fight. (Of Course since then the fight we won has been fought over again and lost - Minnewanka is gone. But it was not our fault.) (I should not say “fought over again”, I fear).

Let me get my breath again and get back to the system of Parks as we visualized them—viz as institutions primarily for the conservation of mankind. Because we wanted to conserve man we found it imperative (or at least important to preserve wild life.

Perhaps at the very beginning when we were feeling our way we simply recognized that wild things had an extraordinary attraction for humans and that [ ___ ?] they were, at least, an important factor in the tourist industry on which we were then specializing. If we were selling the wilderness we would not be giving full value (or get the best returns) unless we had an ample supply of W.L. So, we proceeded to see that all parks were made genuine sanctuaries. Your book has some good stories illustrating this.

Wild things will not constantly remain in protected areas and so we naturally had to look for co-operation from the provinces controlling the areas surrounding parks. And just about that time the proposal for a migration Bird Treaty with U.S. began to get under way. Several Domn. Depts were concerned w/ it and the result was the appointment of a Domn. Advisory Wild Life Board. That Board first dealt with the Treaty and then began gathering a perspective on W.L. throughout the Domn. Each province legislated in W.L. from its purely provincial view point. The Board began a campaign to bring about co-operation and co-ordination among the provinces. It was felt that if justice was to be done W.L./and the country). W.L. must be dealt with from

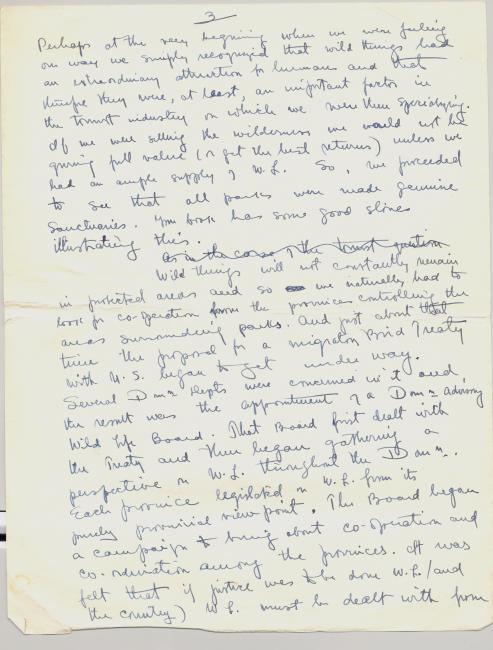

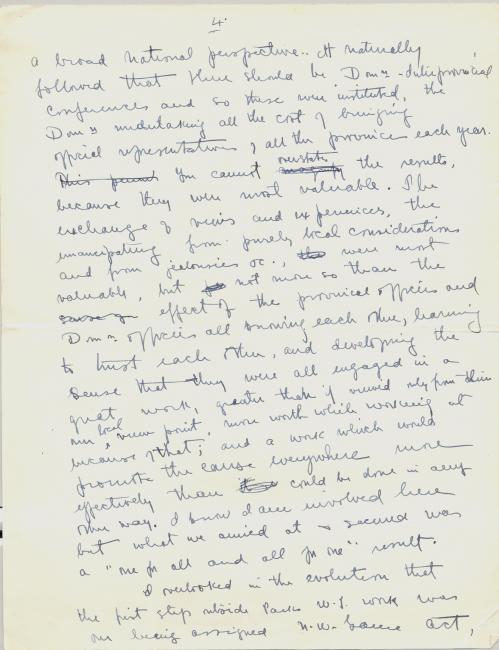

a broad national perspective. It naturally followed that there should be Domn—interprovincial conferences and so these were instituted, the Domn undertaking all the cost of bringing official representatives of all the provinces each year. You cannot overstate the results, because they were most valuable. The exchange of views and experiences, the emancipating from purely local considerations and from jealousies etc., were most valuable, but not more so than the effect of the provincial officers and Domn officers all knowing each other, learning to trust each other, and developing the sense that they were all engaged in a great work, greater than if viewed only from their own local view point, more work which could promote the cause everywhere more effectively than could be done in any other way. I know I am involved here but what we arrived at & secured was a “one for all and all for one” result.

I overlooked in the evolution that the first step outside parks W.L. work was our being assigned N.W. Game Act,

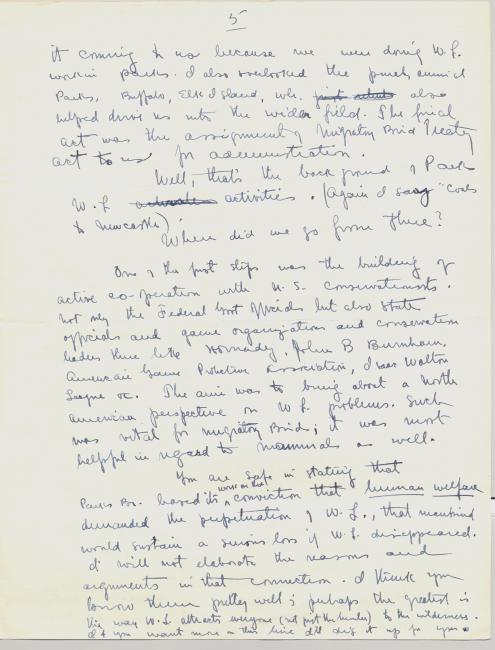

it coming to us because we were doing W.L. work in parks. I also overlooked the purely animal Parks, Buffalo, Elk Island, wh. also helped drive us into the wider field. The final act was the assignment of Migratory Bird Treaty Act to us for administration.

Well, that’s the background of Parks W.L. activities. (Again I say “coals to Newcastle).

Where did we go from there?

One of the first steps was the building of active co-operation with the U.S. Conservationists. Not only the Federal Govt officials but also state officials and game organizations and conservation leaders there like Hornaday, John B Burnham, American Game Protective Association, Isaac Walton League, etc. The aim was to bring about a North American perspective on W.L. problems. Such was vital for migratory birds; it was most helpful in regard to mammals as well.

You are safe in stating that Parks Br. based its work on that conviction that human welfare demanded the perpetuation of W.L., that mankind would sustain a serious loss if W.L. disappeared. I will not elaborate the reasons and arguments in that connection. I think you know them pretty well; perhaps the greatest is the way W.L. attracts everyone (not just the hunter) to the wilderness. If you want more in this line I’ll dig it up for you.

What have we done specifically to conserve? That means details of laws, regulations, education, enforcement laws, scientific study of W.L. conditions and development of solutions for problems.

Education—Lectures, pamphlets, newspaper and magazine articles, moving pictures, junior Audubon Societies, etc. But the greatest & most valuable of all was perhaps the discovery & utilization of Grey Owl.

As in the case of “export of scenery” an effort was made to the financial side of the public by shining that wild life constituted a great business fact, with millions invested in it and millions expended upon it each year. I must look up the figures for you. They are striking, we had to go on the old line of presenting the financial side to secure sympathy for the important side.

I almost overlooked the sanctuaries. Huge ones in N.W.T.; scores of them in Prairie Provinces, quite a number on North Shore of Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Re Migratory Birds. You know of the drought problems and botulism: lead poisoning disappearances of eel grass; disappearance of water feeding areas in south (cultivation) ditto re breeding areas in Canada.

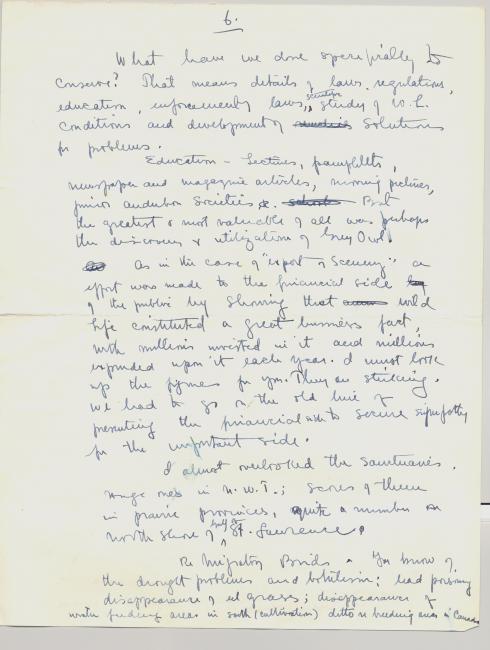

I wrote an article for the American Forestry Journal; will try to dig up a copy for you. It dealt with the attitude of pre-historic man towards W.L., animal statues in middle ages etc. and was designed to justify their idea of getting back to the old idea of man & W.L. being companions & friends etc. I think it wd be useful to you.

I am not going to read this over. I just sat down & wrote. Probably if I read it I wd tear it up.

Write me for specific things you may want. I started looking over some of my “book” notes on W.L. but they were so numerous that it wd be hopeless to start throwing them at you.

This is just a preliminary, dashed-off thing. If it is of any help I will be glad.

Sincerely Yours

JBH

Kind regards from both of us

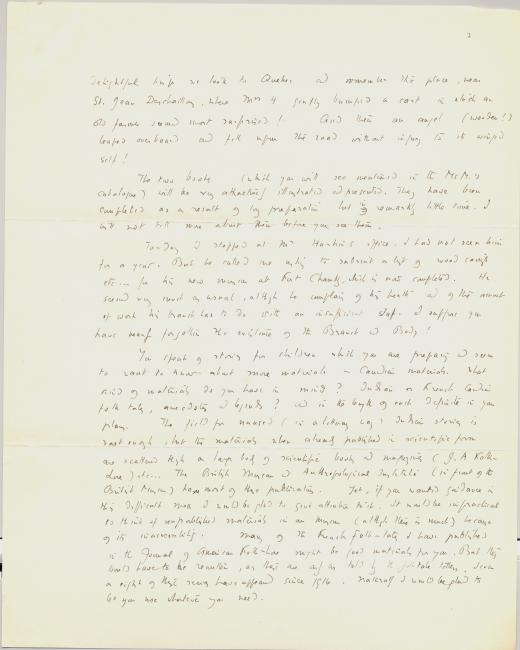

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document. It features letters from Marius Barbeau to MB Williams, 1936 and 1955.

Letters from Marius Barbeau to MB Williams, 1936 and 1955

Marius Barbeau, National Museum of Canada, to MB Williams, 5 March 1936

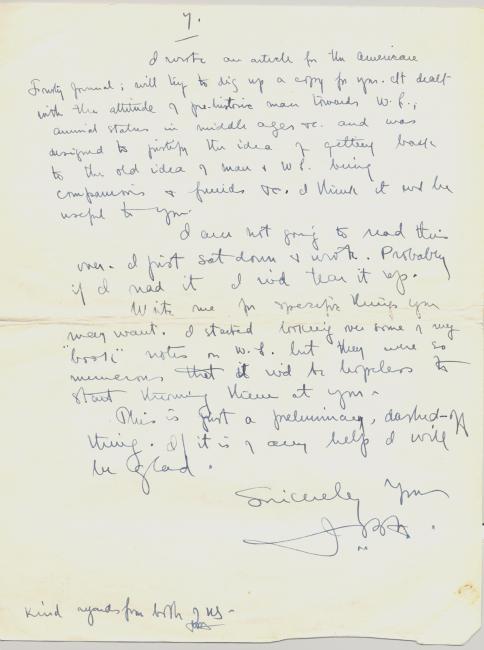

Ottawa, March 5th /36

Dear Miss Williams,

I was delighted to receive your letter, as I have often thought of writing to you but renounced the idea as I did not have your address. You speak of Egalee. It is a strange coincidence that I should yesterday have resumed working on this story. I left it aside even before you did, when you were still in Ottawa and intended at the time to give it a good long rest, but I never thought that this would mean more than six years! I have since been [waylaid] on a scheme of work at writing which left me no time for aught else and which is beginning to bear fruit. I have had 7 or 8 books published in the past two years and several more will come out this coming year. But I am now finding that I have over a month to finish [Mehlala]. Indeed, I revised, shortened and much improved it last summer and had it retyped. Instead of the 65,000 words which you read and revised this part of the text has boiled down to 35,000. I am now building up a third part I intend to bring up the ms to over 50,000. The new part—the 3rd—will concern the relation of Cadieux with the child and his bringing up. All this is involved in an adventure which I am now unfolding and which, I believe, will add to the value and interest of the story.

Tomorrow I will select a copy for you of whatever is due—15 chp, and if you feel so inclined, you may read it and let me hear whatever suggestions you are kind enough to offer; I am still anxious for further improvements. This story is the one on which I will have place the greatest care and affection and you and Mrs. Herridge have helped and encouraged me much. We have had delightful conversations around it. I am sorry there are no large possible on account of the long distance.

You enjoy I hope your prolonged stay in London and abroad. I have had imprecise news of you from time to time. CW was, indeed, glad to hear news coming direct from you. Mrs. Herridge’s son is, I presume, still in London? Give her my affectionate regards. I still often think of the

delightful trip we took to Quebec and remember the place, near St. Jean Deschaillons, where Mrs. H. gently bumped a cart in which an old farmer seemed most surprised! And then an angel (wooden!) leaped overboard and fell upon the road without injury to its winged self!

The two books (which you will see mentioned in McM.’s catalogue) will be very attractively illustrated and presented. They have been completed as a result of long preparation but in remarkably little time. I will not tell more about this before you see them.

To-day I stopped at Mr. Harkin’s office. I had not seen him for a year. But he called me asking to submit a bit on wood carvings etc … for his new museum at Fort Chambly, which is now completed. Seemed very much as usual, although he complained of his health and at the amount his branch has to do with an insufficient staff. I suppose you have nearly forgotten the existence of the Branch and Body!

You speak of stories for children which you are preparing and seem to want to know about more materials—Canadian materials. What kind of materials do you have in mind? Indian or French Canadian folk tales, anecdotes and legends? And is the length of each definite in your plan. The field for unused (in a literary way) Indian stories is vast enough, but the materials when already published in scientific form are scattered [through] a large body of scientific books and magazine (J.A. Folk – Lore) etc … The British Museum and Anthropological Institute (in front of the British Museum) have most of these publications. Yet, if you wanted guidance in this difficult mass I would be glad to give attention to it. It would be impractical to think of unpublished materials in a Museum (although there is much) because of its inaccessibility. Many of the French Folk-tales I have published in the Journal of American Folk-Lore might be good materials for you. But they would have to be rewritten, as there are only as told by the folktale tellers. Seven or eight of these may have appeared since 1916. Naturally I would be glad to let you use whatever you need.

Dalila and Hélène, [the] daughters here, are growing fast. D. is now 16 and is as tall as myself—a difference since you last saw her!

To-morrow I will send you, under another cover, a few publications and various things meant as news. I presume you have been interested in Grey Owl’s peregrination to England? He has just returned and was here in Ottawa last week.

Well, I will hope to hear from you again very shortly.

Affectionately yours

Greetings to Mrs. Herridge

Marius Barbeau

P.S. I will ask Marjorie Borden (from Ottawa) to go and see you. She has worked for me last year to illustrate children’s games and [ ___ ?] dances and this year she has spent 2 ½ months working beside me at the office for the illustration of my last two books. She is a remarkable gay artist and has developed magnificently in the past year, as you will see from the work she has done—illustrations in black and white at chapter heads. She left for England on the first of March. She has taken a copy of [Mehlala] with her to read while sailing.

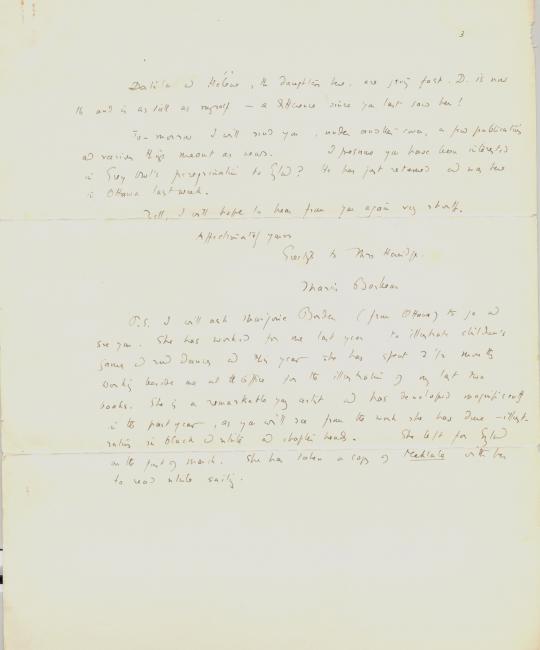

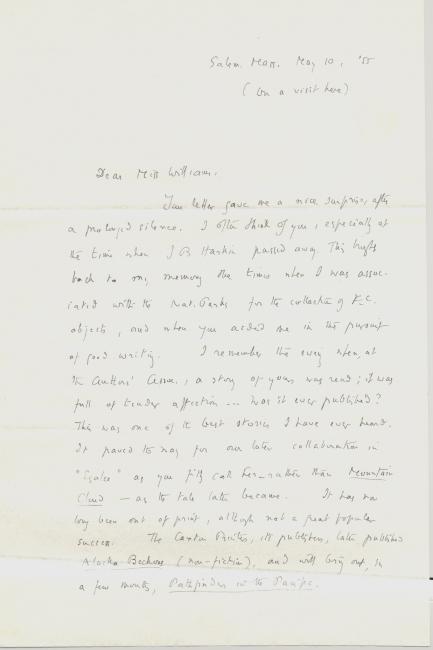

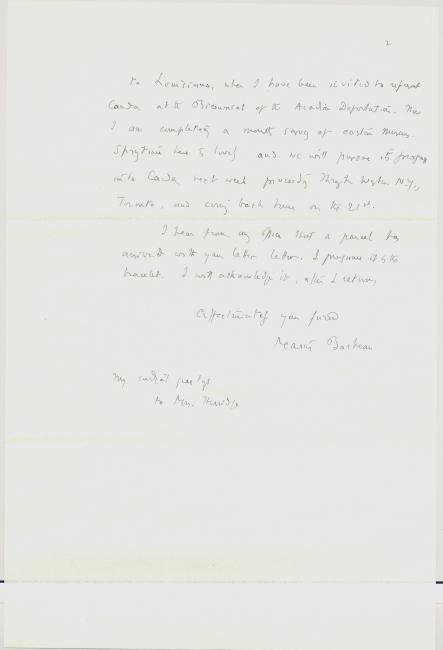

Marius Barbeau (retired) to MB Williams, 10 May 1955

Salem Mass. May 10, ‘55

(On a visit here)

Dear Miss Williams,

Your letter gave me a nice surprise after a prolonged silence. I often think of you, especially at the time when J.B. Harkin passed away. This brought back to my memory the times when I was associated with the Nat. Parks for the collection of F.L. objects, and when you aided me in the pursuit of good writing. I remember the eve’g when, at The Author’s Assoc., a story of yours was read; it was full of tender affection … was it ever published? This was one of the best stories I have ever heard. It paved the way for our later collaboration in “Egalce” as you fitly call her rather than Mountain Cloud — as the tale later became. It has now long been out of print, although not a great popular success. The Caxton Printers, its publishers, later published Alaska Beckons (non-fiction), and will bring out, in a few months, Pathfinder in the Parks.

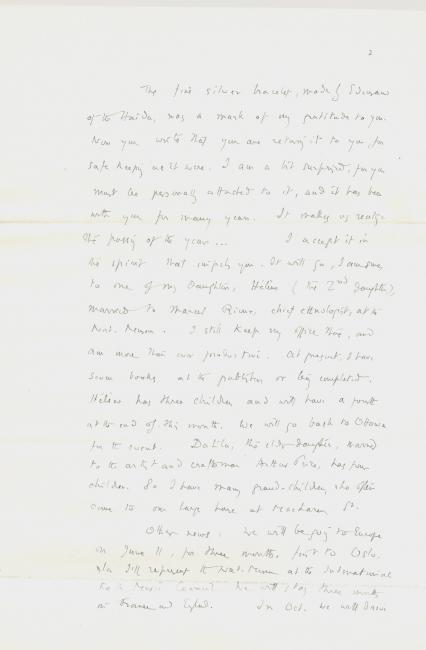

The fine silver bracelet, made by [Edagawn] of the Haida, was a mark of my gratitude to you. Now you wrote that you are returning it to you, for safe keeping as it were. I am a bit surprised, for you must be personally attached to it, and it has been with you for many years. It makes us realize the passing of the years … I accept it in the spirit that impels you. Or will so, I am sure to one of my daughters, Hélène (the 2nd daughter), married to Marcel Rivir, chief ethnologist, at the Nat. Museum. I still keep my office there, and am more than ever productive. At present, I have seven books at the publisher or being completed. Hélène has three children and will have a fourth at the end of this month. We will go back to Ottawa for the event. Dalila, the elder daughter, married to the artist and craftsman Arthur Price, has four children. So I have many grand-children, who often came to our large house at MacLaren St.

Other news: We will be going to Europe on June 11, for three months. First to Oslo, where I’ll represent the Nat. Museum at the International Folk Music Council. We will stay three weeks in France and England. In Oct. we will drive

to Louisiana, where I have been invited to represent Canada at the Bicentennial of the Acadian Deportation. Now I am completing a months survey of eastern [museums]. Springtime here is lovely and we will pursue its progress into Canada next week proceeding through Western N.Y., Toronto, and coming back home on the 21st.

I hear from my office that a parcel has arrived with your letter letter. I presume it is the bracelet. I will acknowledge it, after I return,

Affectionately your friend

Marius Barbeau

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document. This features letters from politicians written to MB Williams, 1936 and 1972.

Letters from politicians to MB Williams, 1936 and 1972

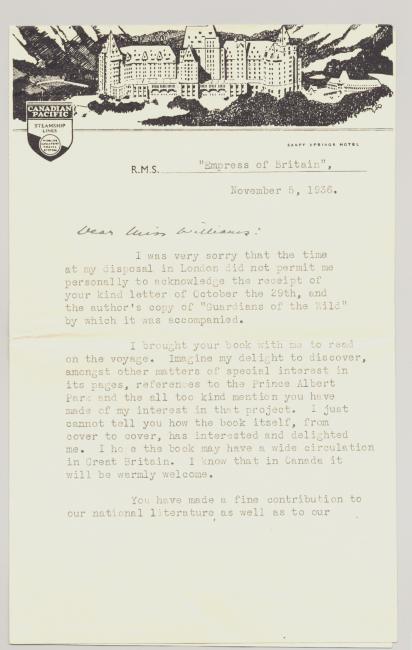

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to MB Williams, 5 November 1936

[Letterhead]

Canadian Pacific

Steamship Lines

Banff Springs Hotel

R.M.S. “Empress of Britain,”

November 5, 1936.

Dear Miss Williams:

I was very sorry that the time at my disposal in London did not permit me personally to acknowledge the receipt of your kind letter of October 29th, and the author’s copy of “Guardians of the Wild” by which it was accompanied.

I brought your book with me to read on the voyage. Imagine my delight to discover, amongst other matters of special interest in its pages, references to the Prince Albert Park and the all too kind mention you have made of my interest in that project. I just cannot tell you how the book itself, from cover to cover, has interested and delighted me. I hope the book may have a wide circulation in Great Britain. I know that in Canada it will be warmly welcome.

You have made a fine contribution to our national literature as well as to our

national policy of seeking to preserve, for other generations as well as our own, some of the “Wild Beauty of the Earth”.

With my warmest thanks for your letter and book,

Believe me, dear Miss Williams,

Yours very sincerely,

W.L. Mackenzie King

Miss Mabel B. Williams

24, Wendover Court,

Lyndale Ave.,

London, N.W. 2,

England.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to MB Williams, 2 December 1936

Personal

Ottawa

December 2, 1936

Dear Miss Williams,

This is only a line to let you know of the due receipt of your letter of November 22nd, and to thank you warmly for its appreciative words, and for the suggestion it contains.

With renewed thanks for your splendid book,

Believe me,

Yours very sincerely,

W.L. Mackenzie King

P.S. Your letter was declared at this time [circle ___?]. It dropped out of sight at the time of ”the constitutional crisis” and was lost track of. WLMK

Miss Mabel B. Williams,

24, Wendover Court,

Lyndale Avenue,

London, N.W.2,

England.

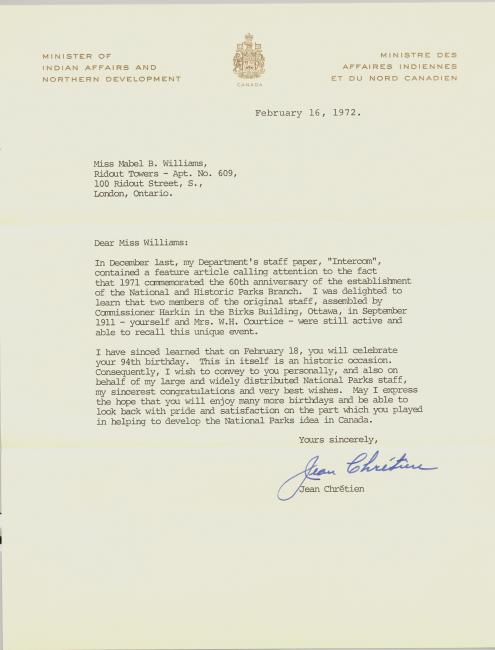

Prime Minister Jean Chrétien to MB Williams, 16 February 1972

[Letterhead]

MINISTER OF INDIAN AFFAIRS AND NORTHERN DEVELOPMENT

Februrary 16, 1972.

Miss Mabel B. Williams,

Ridout Towers-Apt. No. 609,

100 Ridout Street, S.,

London, Ontario.

Dear Miss Williams:

In December last, my Department’s staff paper, “Intercom”, contained a feature article calling attention to the fact that 1971 commemorated the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the National and Historic Parks Branch. I was delighted to learn that two members of the original staff, assembled by Commissioner Harkin in the Birks Building, Ottawa, in September 1911—yourself and Mrs. W. H. Courtice—were still active and able to recall this unique event.

I have since learned that on February 18, you will celebrate your 94th birthday. This in itself is an historic occasion. Consequently, I wish to convey to you personally, and also on behalf of my large and widely distributed National Parks staff, my sincerest congratulations and very best wishes. May I express the hope that you will enjoy many more birthdays and be able to look back with pride and satisfaction on the part which you played in helping to develop the National Parks idea in Canada.

Yours sincerely,

Jean Chrétien

The frontispiece of Guardians of the Wild, written by MB Williams

The frontispiece of Guardians of the Wild, written by MB Williams

Courtesy of Amicus, the Canadian National Catalogue.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Williams and Herridge returned to Canada for good just before the war. At some point, MB alone moved to London, Ontario, to take care of her mother, although she and Herridge remained close. MB then moved to Vancouver following her mother’s death, but in 1949 returned to London, Ontario, to live with her brother after his wife’s death. During this long period, she continued to write—vigorously researching book projects on subjects as diverse as David Thompson and Carl Jung—but apparently never completed anything. Her writing career went nowhere. But at the suggestion of Saskatoon publisher H. R. Larson, she drove—at almost 70 years of age—through the Canadian Rockies for research and inspiration, and reworked some of her old guidebooks, such as The Heart of the Rockies (1947), The Banff-Jasper Highway (1948), and Jasper National Park (1949). Larson also helped MB in compiling and publishing J. B. Harkin’s papers posthumously as The History and Meaning of the National Parks of Canada (1957). It is as if only when writing about the national parks that she had the passion and commitment to see things through.

MB’s house on Queens Avenue, London, Ontario (post-1949)

MB’s house on Queens Avenue, London, Ontario (post-1949)

Photographer and date unknown.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In the 1960s, MB corresponded regularly with longtime park staffer W. F. Lothian, who was writing a four-volume official history of Parks Canada. She shared with him her memories of the park service’s early years, crediting Harkin more than ever for his leadership and brilliance. MB Williams died in 1972. When Lothian finally completed the first volume of his history four years later, he sent a copy to Williams’s close friend Eleanor Shaw. On reading it, Shaw was distressed to find that Harkin and other senior civil servants and politicians receive all the recognition; Williams’s name barely appears. Shaw told Lothian bluntly, “It is dreadful to think that Miss Williams is given no credit for the vital and important work she did for the national Parks, in making known to Canadians the great treasure that was now theirs for all time.”

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document. This features letters between W. F. Lothian and MB Williams, and between W. F. Lothian and Eleanor Shaw (MB’s close friend) 1960-1980.

Letters between W. F. Lothian and MB Williams, and between W. F. Lothian and Eleanor Shaw (MB's close friend) 1960-1980

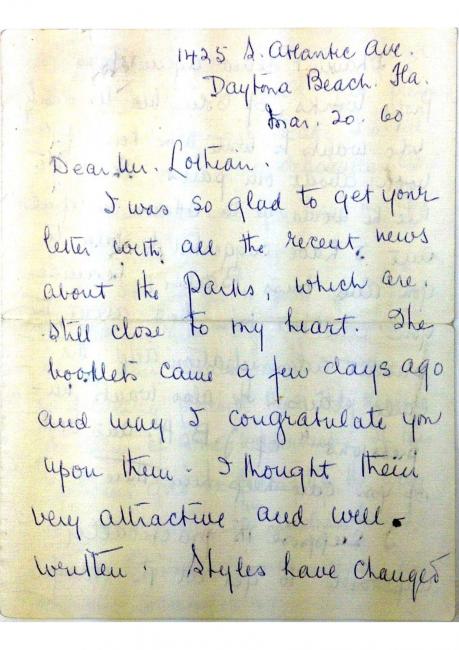

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, Assistant Chief (and parks historian), Parks Branch, 20 March 1960

Dear Mr. Lothian:

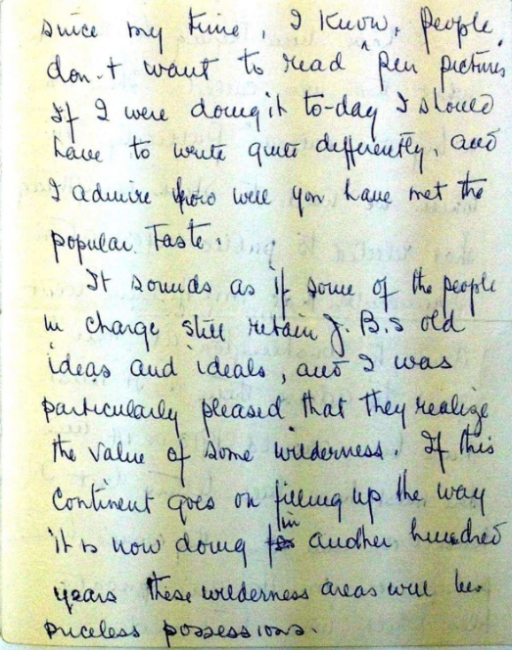

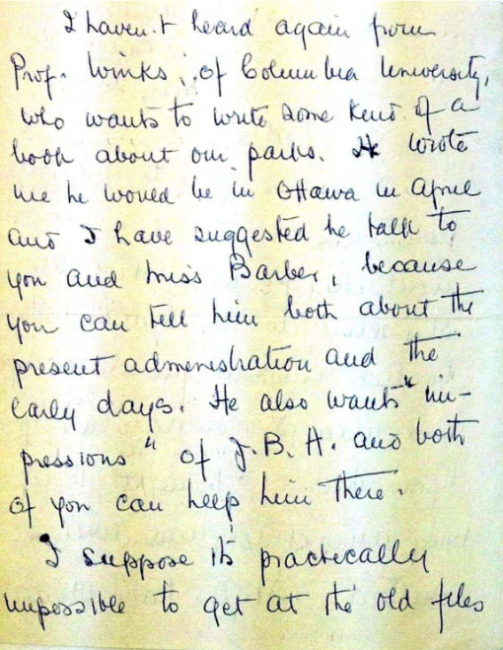

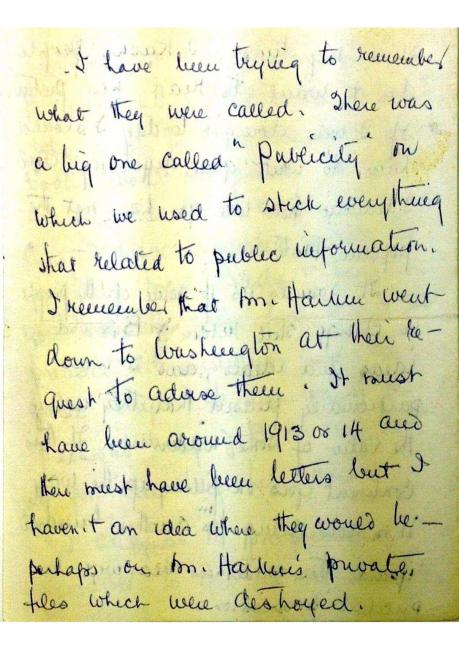

I was so glad to get your letter with all your recent news about the Parks, which are still close to my heart. The booklets came a few days ago and may I congratulate you upon them. I thought them very attractive and well-written. Styles have changed

since my time, I know. People don’t want to read “pen pictures.” If I were doing it to-day I should have to write quite differently, and I admire you well you have met the popular taste.

It sounds as if some of the people in charge are still retaining J.B.s old ideas and ideals, and I was particularly pleased that they realize the value of some wilderness. If this continent goes on filling up the way it is now doing in another hundred years these wilderness areas will be priceless possessions.

I haven’t heard again from Prof. Winks, of Columbia University, who wants to write some kind of a book about our parks. He wrote me he would be in Ottawa in April and I have suggested he talk to you and Miss Barber, because you can tell him both about the present administration and the early days. He also wants “impressions” of J.B.H. and both of you can help him there.

I suppose it’s practically impossible to get at the old files

I have been trying to remember what they were called. There was a big one called “Publicity” on which we used to stick everything that related to public information. I remember that Mr. Harkin went down to Washington at their request to advise them. It must have been around 1913 or 14 and there must have been letters but I haven’t an idea where they would be—perhaps on Mr. Harkin’s private files which were destroyed.

W. F. Lothian to MB Williams, 13 June 1967

Dear Miss Williams:

What a pleasant surprise to receive your letter of May 29, 1967! My first thought on going through the pages was that you have lost nothing of the vigour in your writing which I remembered from long ago. It is wonderful to have a memory such as yours and to be able to recall on the spur of the moment happenings of half a century ago.

Yes, I am trying to work up a history of the establishment and development of the National Parks. I as slated for retirement some time ago and my former position of Assistant Chief, National Park Service, was filled, but the Director, Mr. Coleman, asked me if I would stay on and help out during a staff crisis. Later I was assigned to the present job. Plans are that I will develop a history of each individual park and then compile a lengthy foreword. This will incorporate such items as how the Parks Branch came into being, how policy was developed, the institution of various features of our work such as promotion of tourist travel, construction of trunk highways, preservation of historic sites, conservation of nature, etc., etc. It looks like quite a job, but we already have on file a substantial nucleus in the form of brief draft histories of development and notes on most parks compiled by the various Park Superintendents.

I have already completed a chapter on Kootenay National Park and have done considerable work on Banff and Jasper Parks. Unfortunately, one of our key men in charge of lands and properties died suddenly in January and I was thrown into the breach to supervise the work until the position could be filled. This was done quite recently and I hope to get back to my labour of love soon.

Fortunately, some years ago I compiled bound histories of the illustrated reports of the Commissioner, Director, etc., and have these dating back to 1909. They have been a wonderful source of

information over the years. We also now have a well-stocked and documented library in our building (Centennial Tower) which houses the entire Department. This is a far cry from the 1930’s when we were scattered all over town.

The notes which you have provided in your letter are very instructive and helpful. I have been digging into the annual reports as far back as 1883 and I have already consulted your informative little book “Guardians of the Wild”.

The former National Parks Branch has been expanded considerably over the past few years. It is now composed of the Executive Division with three Assistant Directors; National Parks Service with Operations and Planning Divisions; Engineering and Architectural Division; Canadian Historic Sites Division; Interpretation and Natural History Division; Information Division, Personnel Adviser, and Financial and Management Division. Moreover, we have regional offices at Calgary, Alberta; Cornwall, Ontario; and at Halifax, Nova Scotia, each under a Regional Director, with staff of Parks and Historic Sites Officers, Engineer(s), Clerical, etc. Most of the policy decisions are still made in Ottawa, and the Lands and Property records are still centred here. The Canadian Wildlife Service recently was given full Branch status and functions as a separate unit.

I was interested in your comments on the publicity activities of the old days. I am pretty well acquainted with these, and it came as a shock to one of my former Chiefs (Mr. W.W. Mair) when I told him that in 1930 when I joined the Parks Branch there were 24 individuals in the Publicity Division. As you probably know, this Division was decimated after you left the Department and has never regained its former status and prestige as much of its former work was absorbed by the National Film Board and the Canadian Government Travel Bureau. The enclosed chart may be of interest.

One has only to go through the old annual reports commencing in 1912 and read in the forewords Commissioner Harkin’s ideas on what should be done for National Parks and the conservation of nature. He certainly was years ahead of his time. Strange to say, it is much easier to compile the history of the earlier days than that of more recent years. Our annual reports no longer contain detailed reports of the past years’ activities and what is assembled must be gleaned from the files. Again we are up against difficulties as the Canadian Government instituted a file disposal system some years ago and a number of our files which would have proved useful in compiling historical data have been destroyed!

I am mailing you for perusal, a couple of copies of our staff magazine “Intercom” which contains little articles I contributed to help the editor out. This little publication is a staff magazine which normally is issued quarterly. Your letter has given me a real “lift”. I do hope I can get down your way and have a chat with you before too long. Bert Spero lives in Thamesville and I saw him a few years ago

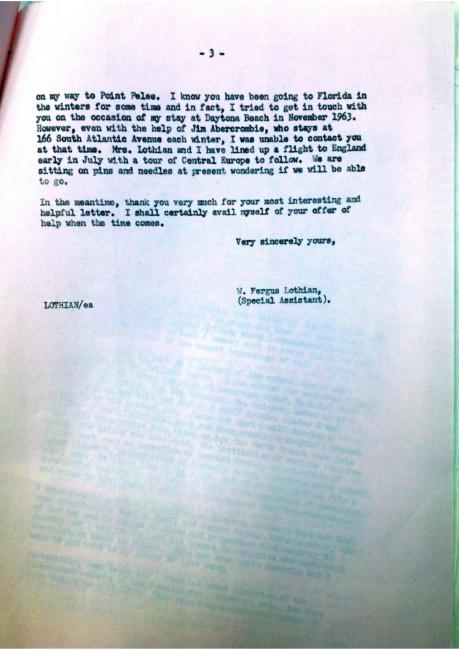

on my way to Point Pelee. I know you have been going to Florida in the winters for some time and in fact, I tried to get in touch with you on the occasion of my stay at Daytona Beach in November 1963. However, even with the help of Jim Abercrombie, who stays at 166 South Atlantic Avenue each winter, I was unable to contact you at the time. Mrs. Lothian and I have lined up a flight to England early in July with a tour of Central Europe to follow. We are sitting on pins and needles at present wondering if we will be able to go.

In the meantime, thank you very much for your most interesting and helpful letter. I shall certainly avail myself of your offer of help when the time comes.

Very sincerely yours,

W. Fergus Lothian, (Special Assistant).

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 15 June 1967

Dear Mr. Lothian:

It was such a pleasure to hear from you and to know of the fine work you are doing. It is a big job you have undertaken, I know, but I can see from your letter and the article in your “Intercom” that you were the person to be chosen to do it. You will have all the information but will know how to make it interesting also. Too bad they burned those old files. Hey would have been a great help to you. There was one, I remember, on which we used to put everything that might be used in the Annual Reports—some of it, of course, left out for lack of space, and some because Mr. Harkin thought that some of his ideas might be considered a little “wild” by the powers that were. He used to say he had a “ten-cent store imagination” and really he could think up a new idea every day.

I am so sorry I missed you in Daytona, I am there every winter and

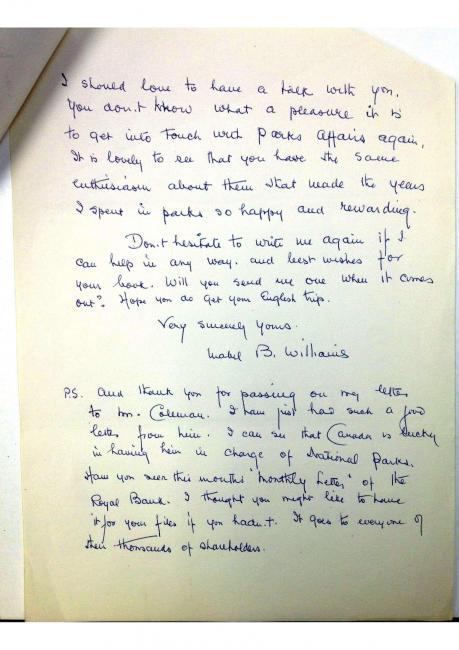

I should love to have a talk with you. You don’t know what a pleasure it is to get into touch with Parks Affairs again. It is lovely to see that you have the same enthusiasm about them that made the years I spent in parks so happy and rewarding.

Don’t hesitate to write me again if I can help in any way, and best wishes for your new book. Will you send me one when it comes out? Hope you do get your English trip.

Very sincerely yours,

Mabel B. Williams

PS. And thank you for passing on my letter to Mr. Coleman. I have just had such a good letter from him. I can see that Canada is lucky in having him in charge of National Parks. Have you seen this month’s “Monthly Letter” of the Royal Bank. I thought you might like to have it for your file if you hadn’t. It goes to everyone of their thousands of shareholders.

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 16 June 1968

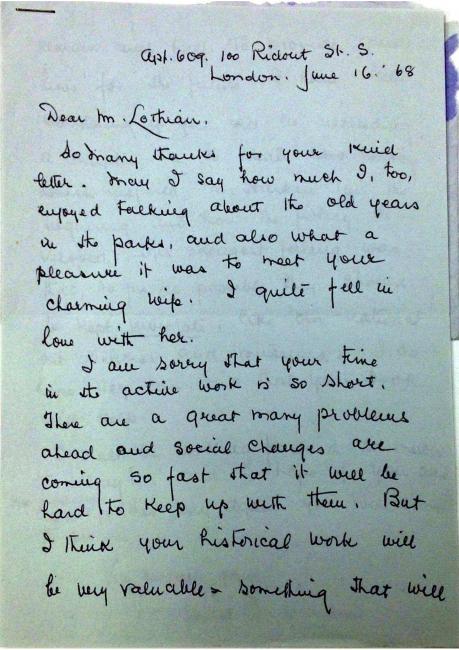

Dear Mr. Lothian:

So many thanks for your kind letter. May I say how much I, too, enjoyed talking about the old years in the parks, and also what a pleasure it was to meet your charming wife. I quite fell in love with her.

I am sorry that your time in the active work is so short. There are a great many problems ahead and social changes are coming so fast that it will be hard to keep up with them. But I think your historical work will be very valuable—something that will

MB Williams to Mr. & Mrs. W. F. Lothian, 11 December 1968

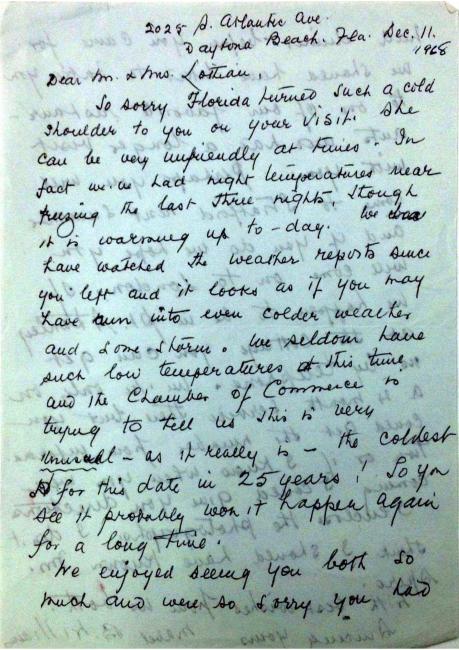

Dear Mr. & Mrs. Lothian:

So sorry Florida turned such a cold shoulder to you on your visit. She can be very unfriendly at times. In fact we’ve had night temperatures near freezing the last three nights, though it is warming up to-day. We have watched the weather reports and it looks as if you may have run into even colder weather and some storm. We seldom have such low temperatures at this time and the Chamber of Commerce is trying to tell us this is very unusual—as it really is the coldest for this date in 25 years! So you see it probably won’t happen again for a long time.

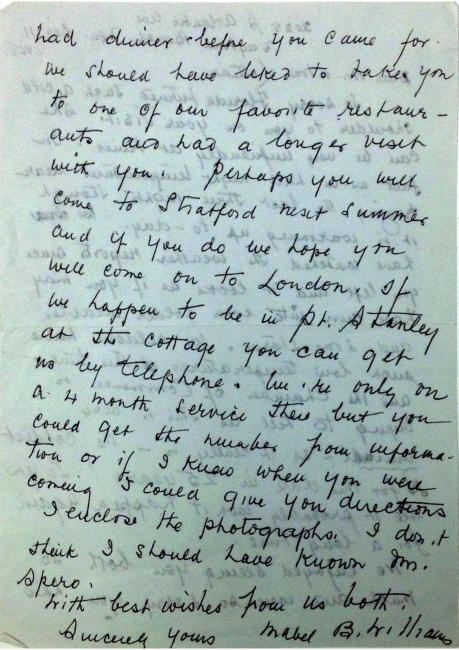

We enjoyed seeing you both so much and were so sorry you had

had dinner before you came for we should have liked to take you to one of our favorite restaurants and had a longer visit with you. Perhaps you will come to Stratford next summer and if you do we hope you will come on to London. If we happen to be in Pt. Stanley at the cottage you can get us by telephone. We’re only on a 4-month service there but you could get the number from information or if I knew when you were coming I could give you directions. I enclose the photographs. I don’t think I should have known Mr. Spero.

With best wishes from us both. Sincerely yours,

Mabel B. Williams

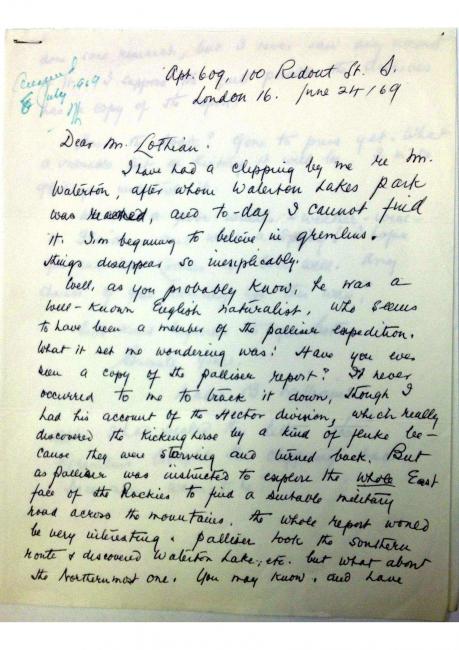

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 24 June 1969

Dear Mr. Lothian:

I have had a clipping by me re M. [?] Waterton, after whom Waterton Lakes Park was named [?], and to-day I cannot find it. I’m beginning to believe in gremlins. Things disappear so inexplicably.

Well, as you probably know, he was a well-known English naturalist, who seems to have been a member of the Palliser expedition. What it set me wondering was: Have you ever seen a copy of the Palliser report? It never occurred to me to track it down, though I had his account of the Hector division, which really discovered the Kicking Horse by a kind of fluke because they were starving and turned back. But as Palliser was instructed to explore the whole East face of the Rockies to find a suitable military road across the mountains, the whole report would be very interesting. Palliser took the southern route & discovered Waterton Lake, etc. but what about the Northernmost one. You may know, and have

done some research, but I never saw any account of it. I suppose its quite possible the Archives has a copy of the report.

How is the book? Gone to press yet. What a valuable bit of history it will be. I’m so glad you undertook it.

We had a poor winter—weather-wise —in Florida, and what a Spring! I hope you and Mrs. Lothian are both well. Any chance of your coming up this way?

With best regards to you both.

Sincerely yours,

Mabel B. Williams

After I had sealed this letter the Gremlins brought the clipping back. Nice [?] man, wasn’t he?

W. F. Lothian to MB Williams, 24 July 1969

Dear Miss Williams:

I am sending you under separate envelope a photo copy of the draft of the first chapter of my history. If you would be good enough to look this over and return with any observations, it would be appreciated.

It will be impossible, within the limits I have set out, to tell everything that has happened in the parks since 1885 and the present. However, after a rather detailed start, I plan to highlight the various developments as set out in the proposed chapter headings. The information I have set out herewith, has to my knowledge, never been published, and I thought it would be in the public interest to show just how hard it was to get the National Park movement really on its way.

In addition to the main dish, I am preparing historical sketches for use in planning division reports for each park. These later can be expanded into histories of each National park. Whether I’ll live long enough to do them (if I’m engaged), no one knows. I have been working on Jasper Park the past two weeks. Then I’ll go back to Chapter Two, for which I have assembled considerable data.

This material is going forward to you at Government expense, but I have enclosed a stamped addressed envelope in which you can return the MSS with your comment,

(over)

If you write a letter, please send it separately to avoid postal regulation infractions. (First class postage on printed material is now almost prohibitive.

Hope you enjoy at least part of my “diggings”. It even may be new to you.

With kindest regards,

W.F. Lothian

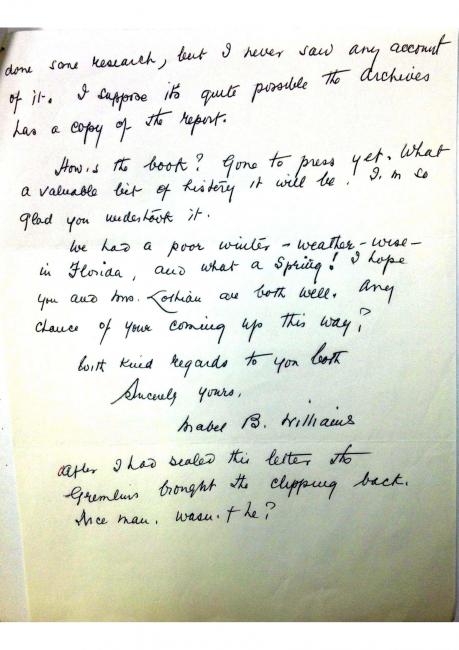

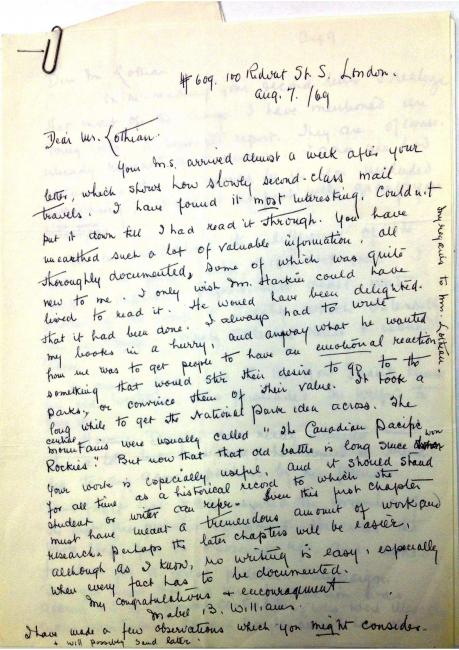

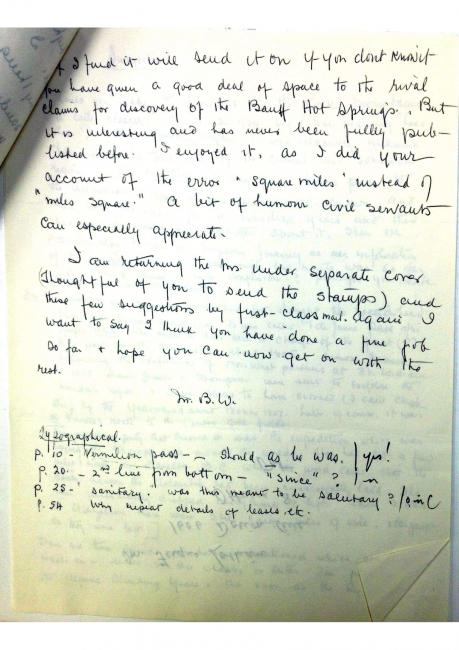

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 7 August 1969

Dear Mr. Lothian:

Your m.s. arrived almost a week after your letter, which shows how slowly second-class mail travels. I have found it most interesting. Couldn’t put it down till I had read it through. You have unearthed such a lot of valuable information. All thoroughly documented, some of which was quite new to me. I only wish Mr. Harkin could have lived to read it. He would have been delighted that it had been done. I always had to write my books in a hurry, and anyway what he wanted from me was to get people to have an emotional reaction, something that would stir their desire to go to the parks, or convince them of their value. It took a long while to get the National Park idea across. The central mountains were usually called “The Canadian Pacific Rockies.” But now that that old battle is long since won your work is especially useful. And it should stand for all time as a historical record to which the student or writer can refer. Given this first chapter must have meant a tremendous amount of work and research, perhaps the later chapters will be easier. Although, as I know, no writing is easy, especially when every fact has to be documented.

My congratulations & encouragement.

Mabel B. Williams

I have made a few observations which you might consider & will possibly send later.

[“My regards to Mrs. Lothian” vertically along margin]

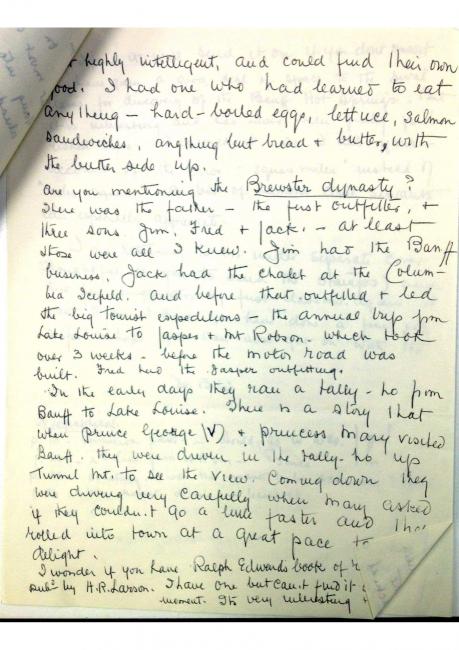

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 9 August 1969

Dear Mr. Lothian

On re-reading your second letter I realize that most of the things I have mentioned are going into a separate report. They are, of course, already recorded and known. I can see how voluminous this one would be if you included everything—I didn’t at first fully grasp your intentions.

You are right about the indifference of the Govt. to the parks until JBH took over. I think 4 different departments dealt with phases of the work & Forestry, which ostensibly was in charge, merely collected rents & issued leases.

We owe the Pablo herd to the Hon. Frank Oliver an old Westerner, who persuaded Sir Wilfrid to buy it.

Howard Douglas was really interested and did a lot, but it is said, he turned a blind eye to any game infractions by his friends.

Don’t forget that JBH inspired the invention of the first fire protection equipment. He called the whole staff, from the messenger up, and asked for ideas for a forest protection campaign. Did you know that his very first action was getting rid of lumber contractors (who were illegally cutting green timber)? Howard Douglas seems to have known it.

[Material missing?] highly intelligent, and could find their own food. I had one who had learned to eat anything—hard-boiled eggs, lettuce, salmon sandwiches, anything but bread & butter, with the butter side up.

Are you mentioning the Brewster dynasty? There was the father—the first outfitter, the three sons Jim, Fred & Jack—at least those were all I knew. Jim had the Banff business. Jack had the chalet at the Columbia Icefield. And before that, outfitted & led the big tourist expeditions—the annual trip from Lake Louise to Jasper & Mt. Robson, which took over 3 weeks—before the motor road was built. Fred had the Jasper outfitting.

In the early days they ran a tally-ho from Banff to Lake Louise. There is a story that when Prince George (V) & Princess Mary visited Banff, they were driven in the tally-ho up Tunnel Mt. to see the view. Coming down they were driving very carefully when Mary asked if they couldn’t go a little faster and they rolled into town a great pace to [ ] delight.

If wonder if you have Ralph Edwards book of [ ] pub’d by H.R. Larson. I have one but can’t find it at the moment. It’s very interesting

If I find it will send it on if you don’t know if you have given a good deal of space to the rival claims for discovery of the Banff Hot Springs. But it is interesting and has never been fully published before. I enjoyed it, as I did your account of the error “square miles” instead of “miles square.” A bit of humour civil servants can especially appreciate.

I am returning the ms under separate cover (Thoughtful of you to send the stamps) and these few suggestions by first-class mail. Again I want to say I think you have done a fine job so far & hope you can now get on with the rest.

M.B.W.

Typographical

p.10 – Vermilion pass – Shouls as be was. [Answer: “Yes!”]

p.20 – 2nd line from bottom – “since”? [Answer: ditto]

p.25 – “sanitary.” Was this meant to be salutary? [Answer: “O in C”]

p.54 Why repeat details of leases, etc.

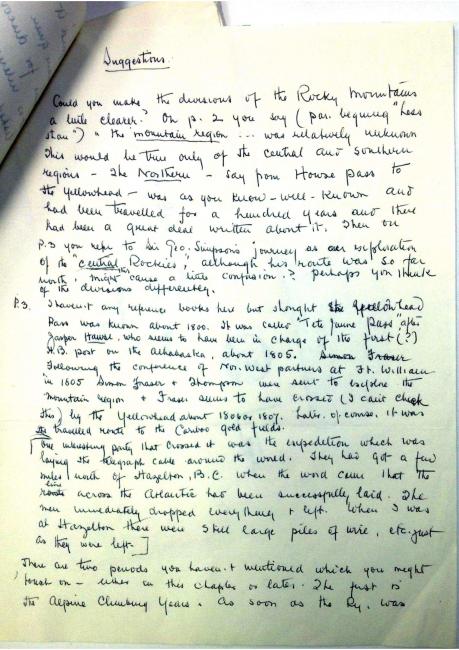

Suggestions

Could you make the divisions of the Rocky Mountains a little clearer? On p.2 you say (par. beginning “less than”) “the mountain region …was relatively unknown This would be true only of the central and southern regions—the Northern—say from Howse pass to the Yellowhead—was as you known well-known and had been travelled for a hundred years and there had been a great deal written about it. Then on p.3 you refer to Sir Geo. Simpson’s journey as an exploration of the “central Rockies,” although his route was so far north, might cause a little confusion? Perhaps you think of the divisions differently.

p.3 I haven’t any reference books here but thought the Yellowhead Pass was known about 1800. It was called “Tete Jaune Pass” after Jasper Hawse, who seems to have been in charge of the first (?) H.B. post on the Athabaska, about 1805. Following the conference of Nor.West partners at Ft. William in 1805 Simon Fraser & Thompson were sent to explore the mountain region & Fraser seems to have crossed (I can’t check this) by the Yellowhead about 1806 or 1807. Later, of course, it was the travelled route to the Cariboo gold fields.

[One interesting party that crossed it was the expedition which was laying the telegraph cable around the world. They had got a few miles north of Hazelton, BC when the word came that the line across the Atlantic had been successfully laid. The men immediately dropped everything & left. When I was at Hazelton there were still large piles of wire, etc. just as they were left.]

There are two periods you haven’t mentioned which you might touch on—either in this chapter or later. The first is the Alpine Climbing Years. As soon as the Ry was

W. F. Lothian to MB Williams, 22 August 1969

Dear Miss Williams:

I appreciated very much the interest you have shown in the manuscript I forwarded to you for review, and which has been duly received. I must apologize for typing errors. It was done by one of the junior typists, and as I am getting that service gratis, I couldn’t complain. Unfortunately I had copies made before I caught out all the inconsistencies.

I intend to cover the Pablo buffalo herd purchase and the forest conservation program in later chapters. I have a copy of an article prepared by Mr. Harkin for the Commission of conservation, together with copies of photos, sketches, etc. which have been handed down from Captain Sparks. Harry Johnston, who as a member of the Railway Commission staff, helped design the fire-engine, still lives in Ottawa. His son Harry is a prominent member of the Historic sites and parks division.

For some time I have been trying to assemble a history of the Brewster family. A niece of Fred Brewster, who, incidentally died this summer, is in charge of a new public records building at Banff, the Archives of the Canadian Rockies. Funds for its construction were supplied by a wealthy resident of Banff, Mrs. Peter Whyte. She was an American, Catherine Robb.

Now with regard to your specific comment. The word “sanitation” in the Order in Council reserving the Banff Hot Springs is the actual wording, although the framers may have been thinking of health. The Oxford Dictionary explains that the word “sanitary” means “free from or designed to obviate influences deleterious to health”, and I think the 1885 officers of the Department had in mind the health advantages of the springs.

I agree that the hot springs controversy occupied quite a lot of space, but as you say, it has never been published, and we have had considerable correspondence with the descendants of William McCardell, who want their father recognized as the discoverer of the springs. I think I can trim the material on the lease hassle which led to the discharge of George Stewart as the first Park Superintendent.

In mentioning the early explorers, I tried to confine them to those who actually traversed lands now in the National Parks. Simon Fraser did not cross the Yellowhead Pass, as far as I can ascertain. We have a copy of his journals from 1804 to 1808, edited by Kaye Lamb, the former Dominion Archivist. The Encyclopedia Canadiana states that the first recorded cor [sic] crossing of Yellowhead Pass was in 1827. Robert Douglas in the book “A Guide to Jasper Park[“], gives it as 1825. We have on file a good paper on Jasper compiled by the late Judge Howay, who was a former member of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board.

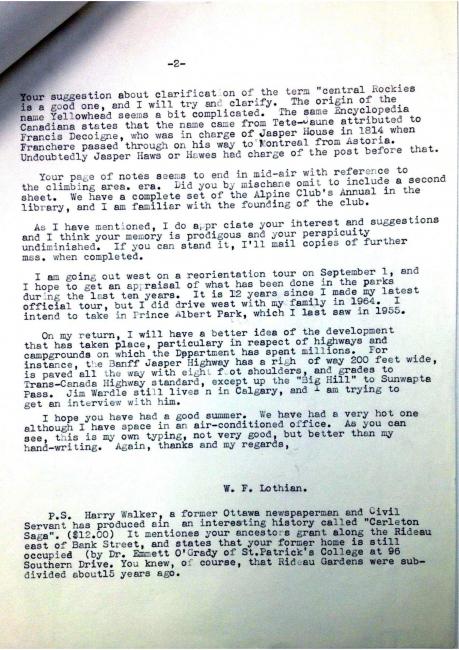

Your suggestion about clarification of the term “central Rockies” is a good one, and I will try and clarify. The origin of the name Yellowhead seems a bit complicated. The same Encyclopedia Canadiana states that the name change came from Tete-Jaune attributed to Francis Decoigne, who was in charge of Jasper House in 1814 when Franchere passed through on his way to Montreal from Astoria. Undoubtedly Jasper Haws or Hawes had charge of the post before that.

Your page of notes seems to end in mid-air with reference to the climbing area. era. Did you by mischance omit to include a second sheet. We have a complete set of the Alpine Club’s Annual in the library, and I am familiar with the founding of the club.

As I have mentioned, I do appreciate your interest and suggestions and I think your memory is prodigious and your perspicuity undiminished. If you can stand it, I’ll mail copies of further mss. when completed.

I am going out west on a reorientation tour on September 1, and I hope to get an appraisal of what has been done in the parks during the last ten years. It is 12 years since I made my latest official tour, but I did drive west with my family in 1964. I intend to take in Prince Albert Park, which I last saw in 1955.

On my return, I will have a better idea of the development that has taken place, particularly in respect to highways and campgrounds on which the Department has spent millions. For instance, the Banff Jasper Highway has a right of way 200 feet wide, is paved all the way with eight foot shoulders, and grades to Trans-Canada Highway standard, except up the “Big Hill” to Sunwapta Pass. Jim Wardle still lives in Calgary, and I am trying to get an interview with him.

I hope you have had a good summer. We have had a very hot one although I have space in an air-conditioned office. As you can see, this is my own typing, not very good, but better than my hand-writing. Again, thanks and my regards,

W.F. Lothian

P.S. Harry Walker, a former Ottawa newspaperman and Civil Servant has produced ain an interesting history called “Carleton Saga”. ($12.00) It mentions your ancestors grant along the Rideau east of Bank Street, and states that your former home is still occupied (by Dr. Emmet O’Grady of St. Patrick’s College at 96 Southern Drive. [)] You knew, of course, that Rideau Gardens were subdivided about 15 years ago.

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 16 November 1969

Dear Mr. Lothian,

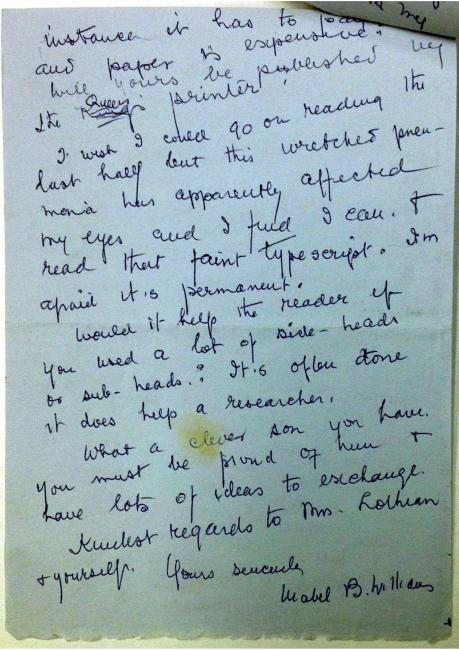

Thanks for your very kind letter but alas! You praised me too soon. A few days after your mss. came I went down with a rather bad flu-pneumonia with heart complications and I’m just now getting on my feet (a little)

I had read the first half of your mss before, I was ill and found it very interesting I think you have done a fine job that will be valuable for all time, you are a natural historian and you have done a job that no one will ever need to do again. You said you wondered about some repetition between the 1st part and the second. I queried that too, at first, but doesn’t it depend upon whom you are writing for. You are not writing for the general public. Your book will be a book of reference — will it even be for sale? Or is for the annals of the dept? It makes a difference. In the first

[Written vertically along edge of page:

“So sorry I couldn’t go to hear Mr. Chretien.—He made a good impression, as does his stand on the Quetico”]

Instance it has to pay and paper is expensive. Will yours be published by the Queens printer. I wish I could go on reading the last half but this wretched pneumonia has apparently affected my eyes and I can’t read that faint typescript. I’m afraid it’s permanent.

Would it help the reader if you used a lot side-heads or sub-heads? It’s often done it does help a researcher.

What a clever son you have. You must be proud of him & have lots of ideas to exchange.

Kindest regards to Mrs. Lothian & yourself.

Yours sincerely,

Mabel B. Williams

My wonderful housekeeper, whom I think you met, was ill all summer and died two weeks ago of cancer. It was a great shock. She was so loyal and capable and I thought would see me out.

If possible I hope to go to Fla. In mid-Dec.

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 27 June 1970

Dear Mr. Lothian,

I had such a kind letter the other day from Mr. Chretien in which he mentioned your name. It is possible that he passed my letter on to you. I had written about the papers relating to Canada’s claim to the Northern Islands because I had always felt a [full?] responsibility about them. Miss Barber had offered them to me but I wrote saying that I thought they should be placed somewhere in the Public Archives, but had never heard exactly what had been done with them. I knew that Mr. Harkin had believed there was something in Stefannson’s belief that the Canadian claim to sovereignty had not been sufficiently established and that for three months he gave a lot of time to the matter. And before the first expedition sailed Capt. Bernier spent about a week in Mr. Harkin’s office, going over the necessary supplies, etc. for the expedition.

How is your own work going? I hope you won’t have to do such a lot of digging after you once get into more recent history. Mr. Chretien

kindly sent me the report on the Wrangel Island affair and I see Mr. Harkin was also a little involved in that. He was a real Canadian interested in everything that was for the good of Canada. You might do a biographical sketch of him sometime. Have you come across his experiments with the tar sands for the Jasper roads, and the utilization of buffalo wool & hides. He also did a lot of work in trying to find a cheap substance for highway surfaces, and he & Mr. Williamson worked many nights trying to get a three-dimensional picture for movies—and ever so many more creative ideas, some of which, of course, came to nothing.

I’m holding my own pretty well, Though both the eyes & the ears, aint what they used to be.

I do hope you & Mrs. Lothian are well.—and busy. Shall be looking for your next chapter some day.

With kindest regards to you both,

Sincerely Mabel B. Williams

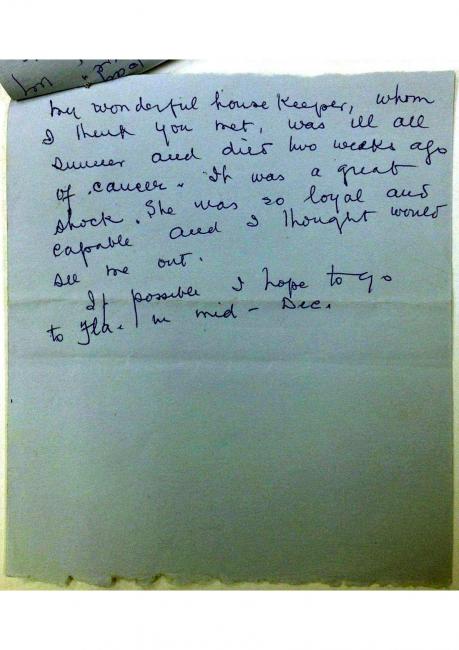

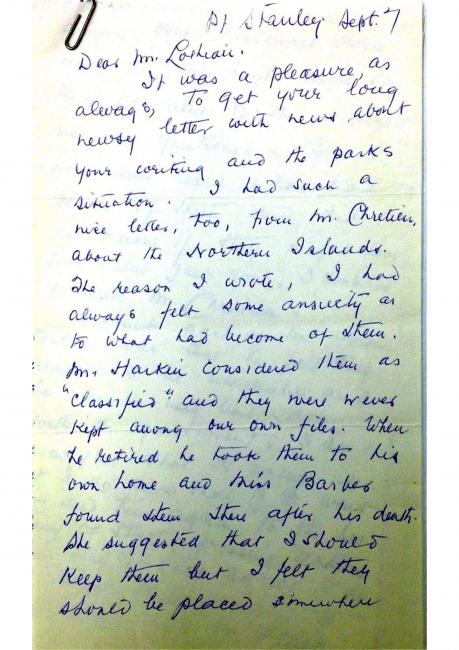

MB Williams to W. F. Lothian, 7 September [1970]

Dear Mr. Lothian,

It was a pleasure, as always, to get your long newsy letter with news about your writing and the parks situation. I had such a nice letter, too, from M. Chretien, about the Northern Islands.

The reason I wrote, I always felt some anxiety as to what had become of them. Mr. Harkin considered them as “classified” and they never were kept among our own files. When he retired he took them to his own home and Miss Barber found them after his death. She suggested that I should keep them but I felt they should be placed somewhere

among other historical documents as they might have some value if the sovereignty was ever questioned. But I had never heard what had become of them and did not know if they might have some value just now. I ventured to write M. Chretien.

I think part of Mr. Harkins was that he felt Stefannsson to be unreliable he was in very bad odour with the government. I don’t know just what the papers were but I do know that J.B. went time and time to the Secretary of State, pressuring action. When they at last agreed to do so, Capt. Bernier came to our office, and Mr. Harkin

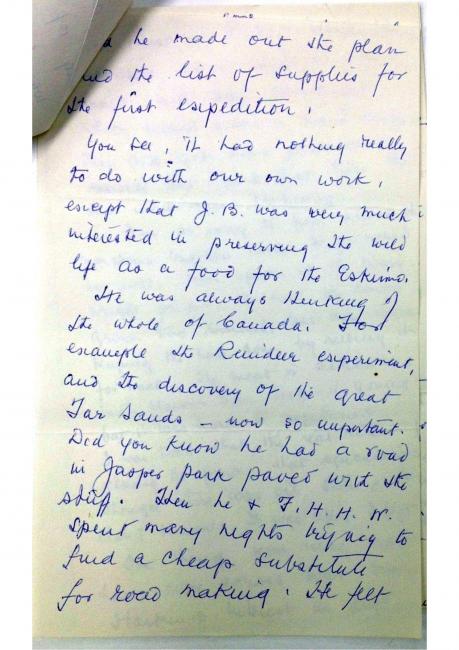

and he made out the plan and the list of supplies for the first expedition.

You see, it had nothing really to do with our own work, except that J.B. was very much interested in preserving the wild life as a food for the Eskimo.

He was always thinking of the whole of Canada. For example the Reindeer experiment and the discovery of the great Tar Sands—now so important. Did you know he had a road in Jasper park paved with the stuff. Then he & FHHW [Williamson] spent many nights trying to find a cheap substitute for road making. He felt

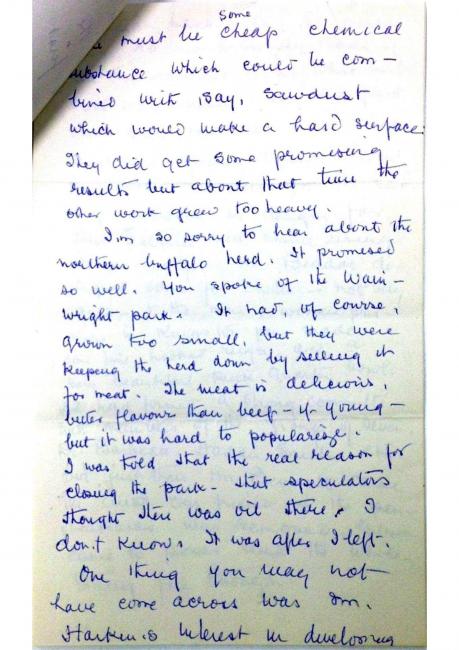

there must be some cheap chemical substance which could be combined with, say, sawdust which would make a hard surface. They did get some promising results but about that time the other work grew too heavy.

I’m so sorry to hear about the northern buffalo herd. It promised so well. You spoke of the Wainwright park. It had, of course, grown too small, but they were keeping the herd down by selling it for meat. The meat is delicious, better flavour than beef—if young—but it was hard to popularize. I was told that the real reason for closing the park—that speculators thought there was oil there. I don’t know. It was after I left.

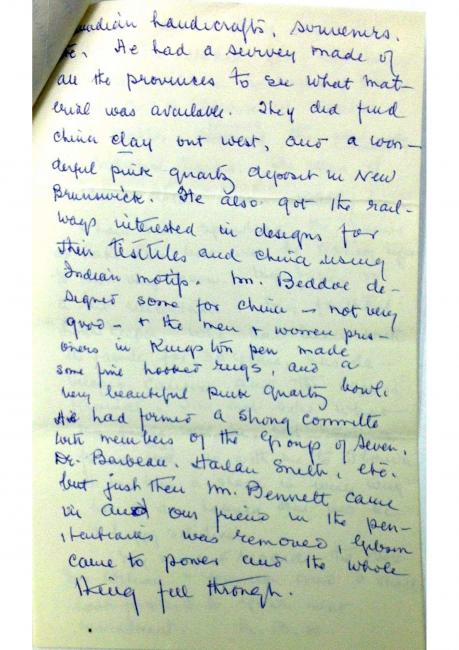

One thing you may not have come across was JB Harkin’s interest in developing

Canadian handicrafts, souvenirs, etc. He had a survey made of all the provinces to see what material was available. They did find china clay out west, and a wonderful pink quartz deposit in New Brunswick. He also got the railways interested in designs for their textiles and china using Indian motifs. Mr. Beddoe designed some for china—not very good—& the men & women prisoners in Kingston pen made some fine hooked rugs, and a very beautiful pink quartz bowl. He had formed a strong committee with members of the Group of Seven, Dr. Barbeau, Harlan Smith, etc. but just then Mr. Bennett came in and our friend in the penitentiaries was removed, Gibson came to power and the whole thing fell through.

[ ] you are writing about him [ ] the credit for starting the whole world in developing tourist travel as a source of income, and really, forming the philosophy of National Parks. The idea of “Wilderness Areas” was wholly his.

I have been spending the summer at Lake Erie but will be going up to town very soon. My future is a bit uncertain, my faithful housekeeper, who had been with the family for 30 years, has developed cancer and the case is terminal. I’m not sure what my future will be, but hope a friend may go with me to Florida. It has been a shock in every way but I am hoping there will be a happy solution.

My kindest regards to both [Mrs.?] Lothian & yourself, and I shall look forward to your next instalment.

M.B.W.

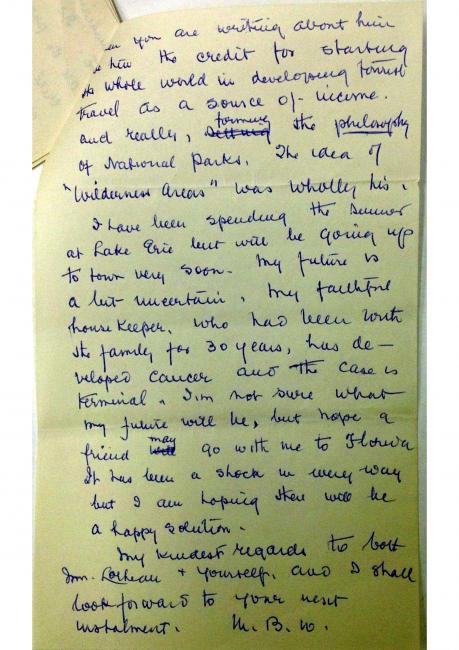

W. F. Lothian to John I. Nicol, Director, Parks Canada, 7 January 1972

Former Branch Staff

A recent issue of the Department’s house organ “Intercom” contained a story describing 1971 as the diamond jubilee of the National Parks Branch. The issue also contained a reproduction of a photograph taken in March, 1913, of the Branch staff, then about 18 months old.

I forwarded copies of the paper to three survivors of the early staff, Miss Mabel Williams, Mrs. W.H. Courtice, and J.E. Spero. Miss Williams of London, Ontario, who will be 94 in February, replied as follows:

“So glad to get your letter and know that you are still at your good work which will be a boon to posterity. Too bad I shall not be able to read it. I can now not even read headlines but write in the dark and hope you can read it a little. The Parks staff must be very large. How do you find its works? Mrs. Courtice and I must be the only members of the original staff left. I think Mr. Chretien has done a fine job in setting aside so much, but people don’t seem to realize yet how much we may need the solitude and wild country. They will soon! ……”

From Mr. Spero, now of Thamesville, Ontario, I heard as follows:

“…We enjoyed the paper you sent. I am in the old age group—85 in another month.” (January 19)

Mrs. Courtice, widow of an early member of the staff who also is portrayed in the 1913 photograph, lives in Ottawa. She will attain the age of 88 on October 26 next.

I am sure you will be interested to learn how durable the original staff of the National Parks Branch really was.

W.F. Lothian,

Branch Historian.

W. F. Lothian to Eleanor Shaw (MB’s close friend), 26 November 1972

Dear Miss Shaw:

I had intended writing to you some time ago, but absences from the citykand some other poor excuses have caused a deferment. May I explain that I was one of Miss Mabel Williams associates in the National Parks Branch many years ago, and over the past five years we began corresponding after she found out that I was writing a history of the National Parks system of Canada.

I was very sorry to learn of Miss Williams death, although I realized that she was running out of time. However, she never lost her enthusiasm for the parks, nor her regard for our former Commissioner, the late J.B. Harkin. I guess what finally prompted me to write you was the fact that quite recently the Department asked me to prepare a short biographican sketch of Mr. Harkin. This I was able to do, largely on information that Miss Williams had furnished.

I have one item on which I would like information. Prior to Miss Williams last birthday, I suggested to the Director of National Parks, Mr. Nicol, that the Minister send her greetings on her birthday. I was delegated to prepare the letter. I know it was signed by Mr. Chretien, and I have always wondered if Miss Williams received the letter before she became too ill to understand its import.

I also would like to know if, among the items forming her estate, she left any early papers belonging to Mr. Harkin, or relating to the early days of the National Parks Branch. I know that her old friend and associate, Miss Dorothy Barber of Ottawa, had custody of some of Mr. Harkin’s papers, which I believe eventually were received in the archives here in Ottawa. If there was anything else, I am sure the Archives would like them.

Miss Williams also had one or more photographs of Mr. Harkin. If any of these were surplus to the requirements of the legatees it would be treasured in the National and Historic Parks Branch as it is now called.

With respect to the history on which I have been working for nearly four years, you may be interested to know that I have completed four chapters, and was able to mention Miss Williams name. As a senior citizen, I haven’t got the stamina of my work output of a few years ago, but manage on an average five hours a day on a five day week.

I shall miss hearing regularly. She was very pleased to learn that some one was writing the Parks history, and I do hope I will be able to finish. The trouble is that history is in the making while I try to recapture the past. Ten new parks have been set aside since I commenced this job.

Well, Miss Shaw, I hope the foregoing will not offend or bore you. It is really meant as a tribute of my high regard for Miss Williams, and my wonder at the stamina she retained to reach the status of a nonagenarian. My last note from her was at Christmas when the apologized for her writing, which she could no longer follow by sight. She certainly was a wonder.

Yours very sincerely,

W. Fergus Lothian

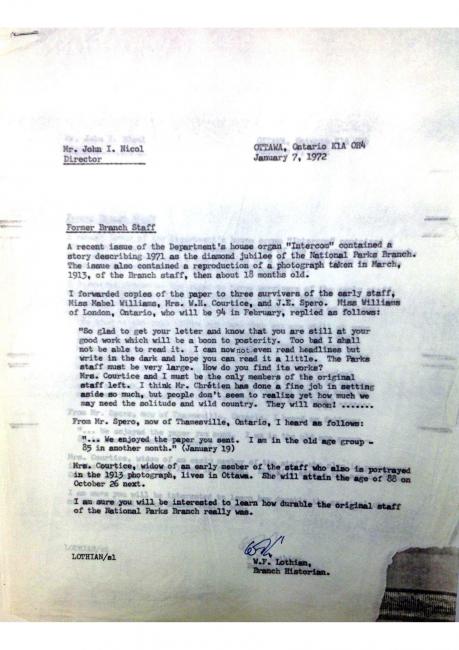

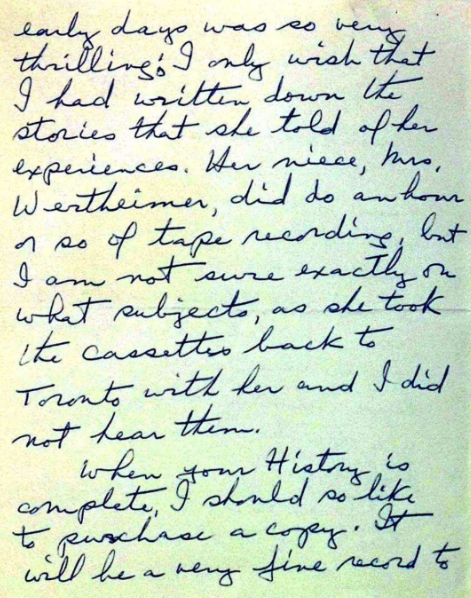

Eleanor Shaw to W. F. Lothian, 20 November 1972 (wrongly dated by Shaw)

Dear Mr. Lothian:

I was very pleased to hear from you, but I am afraid that I cannot be of much help, as the disposal of Miss Williams’ effects was completely in the hands of her nieces. All that I have relating to the Parks are her book and her bulletins.

One thing I can tell you, though, is that she did indeed

receive Mr. Chretien’s letter and that she was deeply pleased by it. It was, if I may make the comment, a most happy thought and you wrote a very warm and gracious and appreciative letter. You have no idea how much pleasure it gave her.

She was also much interested in your history of the National Parks and I hope that the family may have photographs, etc. to send you. Her past in those

early days was so very thrilling! I only wish that I had written down the stories that she told of her experiences. Her niece, Mrs. Wertheimer, did so an hour or so of tape recordings, but I am not sure exactly on what subjects, as she took the cassettes back to Toronto with her and I did not hear them.

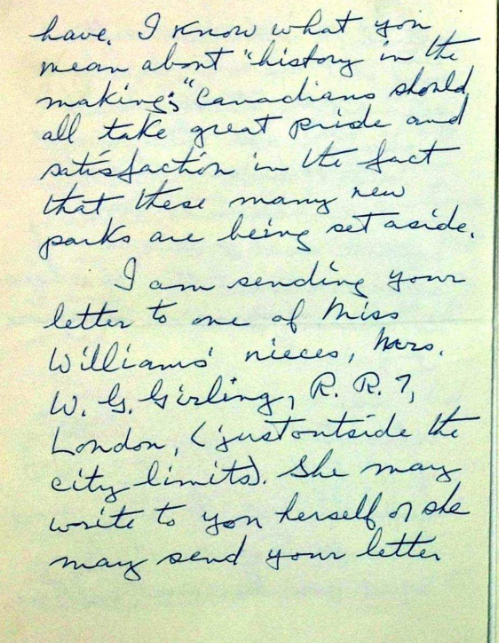

When your History is complete, I should so like to purchase a copy. It will be a very fine record to

have. I know what you mean about “history in the making”; Canadians should all take great pride and satisfaction in the fact that these many new parks are being set aside.

I am sending your letter to one of Miss Williams’ nieces, Mrs. W.G. Girling, R.R.7, London (just outside the city limits). She may write to you herself or she may send your letter

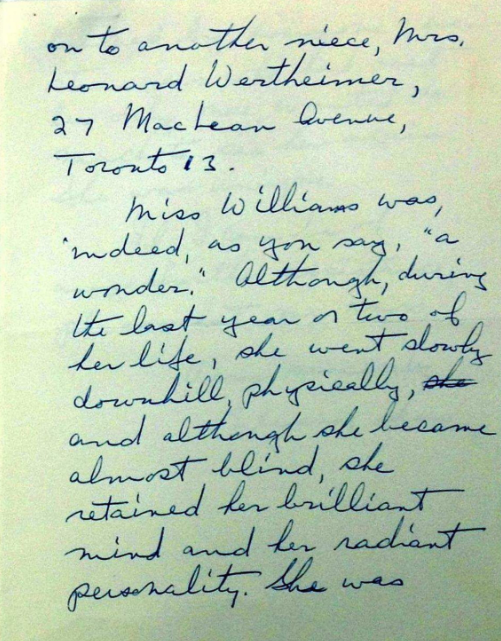

on to another niece, Mrs. Leonard Wertheimer, 27 MacLean Avenue, Toronto 13.

Miss Williams was indeed, as you say, “a wonder.” Although during the last year or two of her life, she went slowly downhill, physically, and although she became almost blind, she retained her brilliant mind and her radiant personality. She was

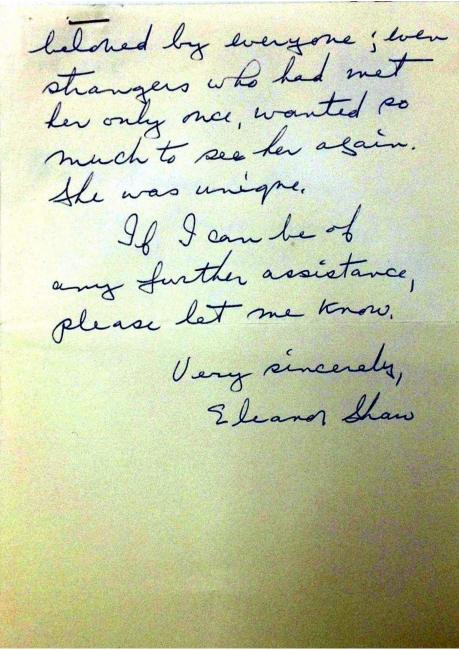

beloved by everyone; even strangers who had met her only once, wanted so much to see her again. She was unique.

If I can be of any further assistance, please let me know,

Eleanor Shaw

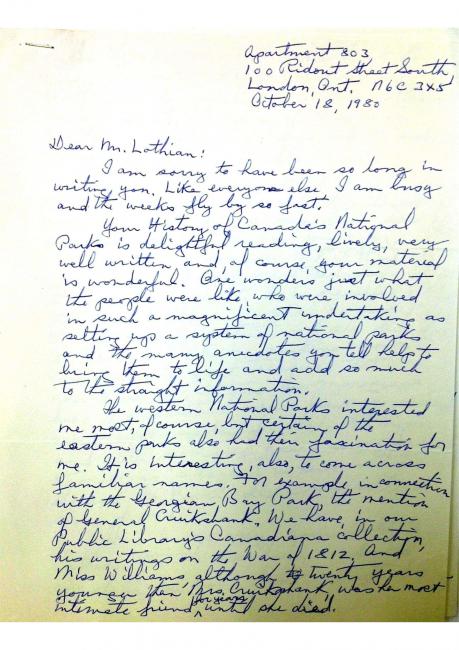

Eleanor Shaw to W. F. Lothian, 18 October 1980

Dear Mr. Lothian:

I am sorry to have been so long in writing you. Like everyone else, I am busy and the weeks fly by so fast.

Your History of Canada’s National Parks is delightful reading, lively, very well written, and, of course, your material is wonderful. One wonders just what the people were like who were involved in such a magnificent undertaking as setting up a system of national parks and the many anecdotes you tell help to bring them to life and add so much to the straight information.

The western National Parks interested me most, of course, but certain of the eastern parks also had their fascination for me. It is interesting, also, to come across familiar names. For example, in connection with the Georgian Bay Park, the mention of General Cruikshank. We have, in our Public Library’s Canadiana collection, his writings on the war of 1812, and Miss Williams, although twenty years younger than Mrs. Cruikshank, was her most intimate friend, for years until she died.

In the beginning of your book, Sir George Simpson’s mention of finding heather made me think of Miss Williams’ little booklet, “A Sprig of Mountain Heather,” in which she goes into the subject extensively and delightfully.

I thought that illustrations and some maps would have added to the interest of your book, but it is a very fine piece of work and I shall treasure my copy.

Every time, however, that I think of your History, I feel great sadness and a strong sense of guilt. It is dreadful to think that Miss Williams is given no credit for the vital and important work she did for the national Parks, in making known to Canadians the great treasure that was now theirs for all time. Her monographs have, I understand, never been superseded and she was spoken of, while still living and after so many years away from the scene, as “a legend in her own time.” She and Mr. Harkin did a marvelous piece of work.

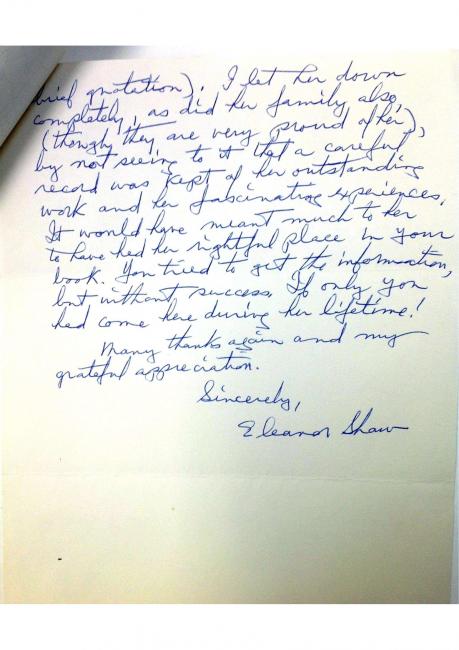

It is in no way your fault, Mr. Lothian, that she has been overlooked completely in your book, (except for a

brief quotation). I let her down completely, as did her family also (though they are very proud of her) by not seeing to it that a careful record was kept of her outstanding work and her fascinating experiences. It would have meant much to her to have had her rightful place in your book. You tried to get the information, but without success. If only you had come here during her lifetime!

Many thanks again and my grateful appreciation.

Sincerely,

Eleanor Shaw

Only twenty of MB’s ninety-four years had involved working in the Canadian national park system. This exhibit, and the documents which comprise it, can hardly claim to have captured her life. And yet in the oral interview that she gave her niece Ruth when almost ninety years old, it is those years with the Parks Branch which continually draw her back, and which make her sound so vigorous. Working alongside Harkin to figure out how to justify parks to Parliament. Travelling with anthropologist Marius Barbeau to see the “last” potlatch held by Indigenous people in British Columbia. Laughing at the “hardship” of staying in a luxurious cabin at Jasper.

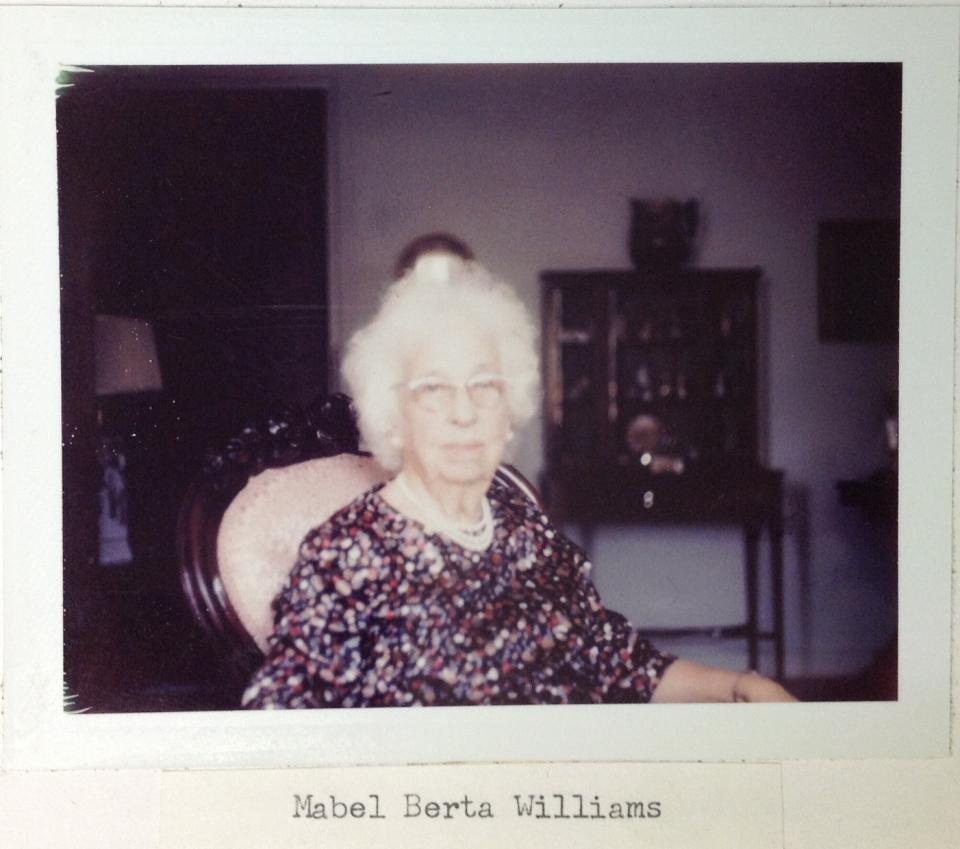

MB Williams in her eighties-nineties. The two audio interviews below focused mostly on MB’s work with the Parks Branch, conducted over two sessions in October 1969 and June 1970 by her niece Ruth and Ruth’s husband Len Wertheimer.

For audio track timelines, please click here.

The original exhibition contains two audio interviews that focused mostly on MB’s work with the Parks Branch, conducted over two sessions in October 1969 and June 1970 by her niece Ruth and Ruth’s husband Len Wertheimer.

MB opened Guardians of the Wild with British socialist writer Edward Carpenter’s line, “I see a great land waiting for its own people to come and take possession of it.” (She had made this something of a mission statement for the Canadian national park system, having used it in two previous publications.) MB Williams’s work writing guidebooks and policy for the fledgling Dominion Parks Branch helped Canadians take emotional and intellectual possession of their land, and build a national park system that rivals any in the world. And it helped her take possession of her land, and her life, too.