The Letters of a Life

Museums tend to have better collections of wedding dresses than work clothes. Archives are likewise often filled with papers that are unrepresentative of peoples’s lives, but are the kinds of papers people keep. MB Williams’s papers suffer somewhat from that affliction: she was more likely to hold onto letters from famous folk such as Parks Branch Commissioner J. B. Harkin, or anthropologist and folklorist Marius Barbeau, or Minister of Natural Resources and future Prime Minister Jean Chrétien than from her own family. But to her family, she was the famous (or at least exotic) one, so they retained a lovely collection of her letters, dating from 1899 to 1972. Whether written in Ottawa or London, England, on cruise ship or hotel stationery, these letters offer a blend of everyday life—toothaches and nylons, friendships and feuds—with social commentary, and the occasional insights into historical figures.

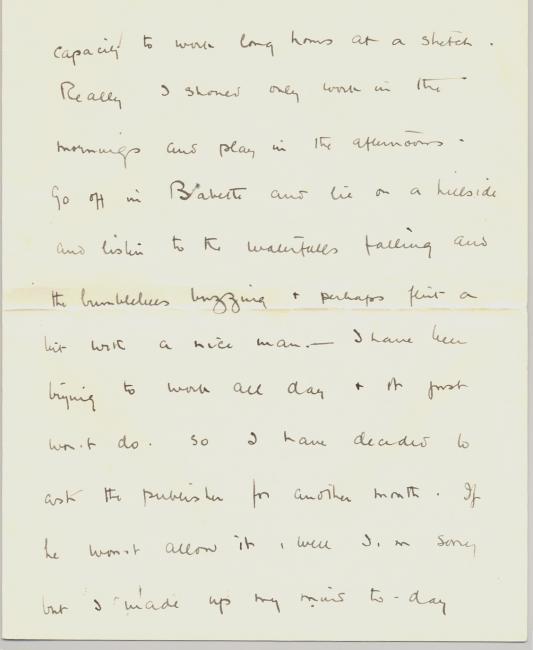

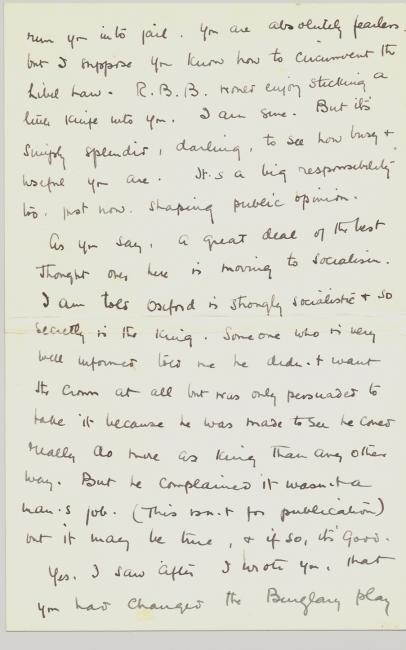

An undated photograph of MB Williams

An undated photograph of MB Williams

M.B. Williams fonds, Library and Archives Canada, R12219-0-3-E

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

MB’s proximity to Canadian Prime Minister R. B. Bennett and his family in the 1930s dramatically shaped her life, in ways both personal and professional. She was a longtime friend and companion of Mary Bird (“Zoe”) Herridge, the stepmother of William Duncan Herridge, Bennett’s policy advisor and husband to his beloved sister Mildred. This drew her into the Bennett orbit, which must have made the draconian staff cuts he imposed early in the Depression all the more upsetting. In a 1930 letter, she tells family of attending the opening of Parliament with Bennett’s sister, watching as the Prime Minister “perspired in gold lace & white satin trousers, cocked hat with the same grim determination with which he raises the tariff & cuts down the Civil Service.” Her own job was likely safe, given her seniority—by this time she oversaw a large staff, including all the women in the Parks Branch headquarters—and her proximity to the Bennetts. But when told to lay off most of her staff, she resigned in solidarity. Ironically, whereas Bennett’s cuts ended her career, it was likely his personal fortune that then subsidized her travel to Europe as companion to Mary Bird Herridge, and their setting up camp in London, England.

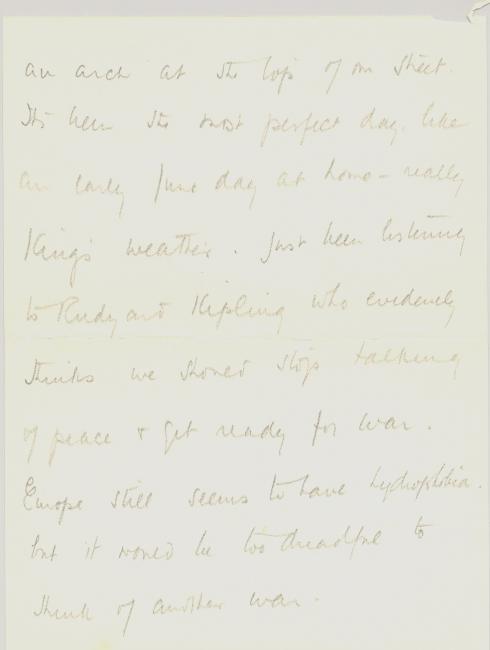

The sixteen letters from MB to family between 1931 and 1935 (five of which are below; the rest can be found in the collection) paint a picture of a woman experiencing life on her own terms. Her very first London letter tells of seeing “the Lord Mayor’s Show” from their window at the Palace Strand Hotel, then going to the opening of the British Parliament, and then off to the Armistice Celebration. She soon tells of her role in writing, with Herridge, the King’s first Empire radio broadcast for Christmas morning, 1932. There are recommendations of authors, descriptions of fashions, updates about health, and lots about her dog and about the car she drives on occasional returns to Ottawa. And there are also the first rumbles of unease in Europe. In 1933, “Hitler … talks like a madman – the same kind of madness that led to war before,” and by 1935, “been listening to Rudyard Kipling who evidently thinks we should stop talking of peace and get ready for war.”

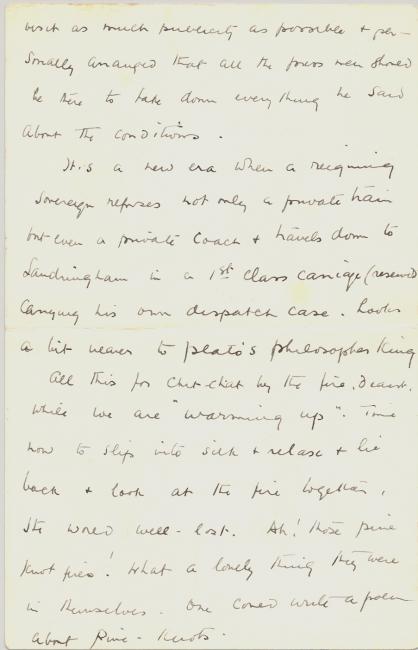

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document. It features five handwritten letters from MB Williams to her family between 1930 and 1935.

Letters from MB Williams to her family

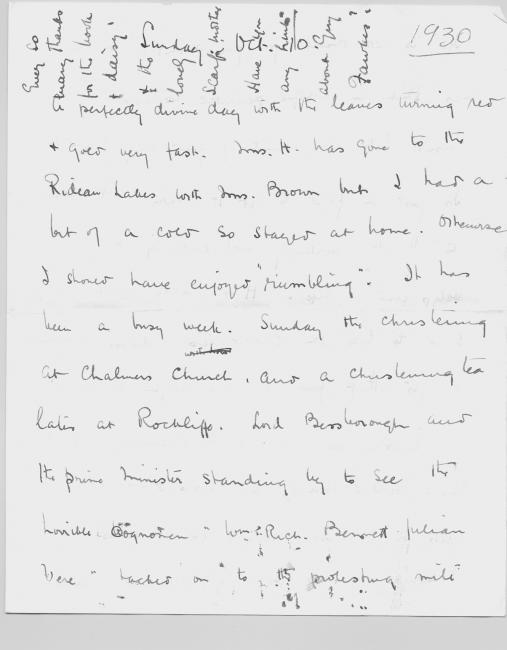

MB Williams to her family, 10 October 1930

1930

Sunday Oct. 10.

[Written vertically across the top of the letter:]

Ever so many thanks for the book & daisy & the lovely scarf Mother. Have you any hints about Guy Fawkes?

A perfectly divine day with the leaves turning red & gold very fast. Mrs. H. has gone to the Rideau Lakes with Mrs. Brown but I had a bit of a cold so stayed at home. Otherwise I should have enjoyed “rambling.” It has been a busy week. Sunday the christening at Chalmers Church, and a christening tea later at Rockcliffe. Lord Bessborough and the prime minister standing by to see the horrible cognomen “Wm Rich Bennet Julian Vere” tacked on to the protesting mite

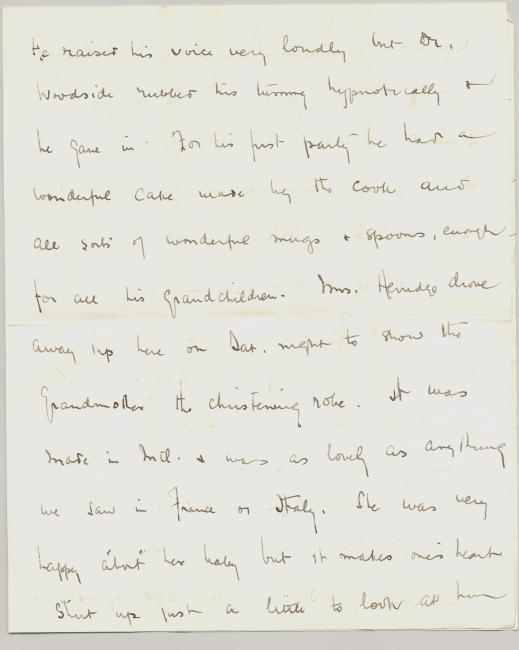

He raised his voice very loudly but Dr. Woodside rubbed his tummy hypnotically & he gave in. For his first party he had a wonderful cake made by the cook and all sorts of wonderful mugs & spoons, enough for all his grandchildren. Mrs. Herridge drove away up here on Sat. night to show the Grandmother the christening robe. It was made in Mil. & was a lovely as anything we saw in France or Italy. She was very happy about her baby but it makes one’s heart start up just a little to look at him.

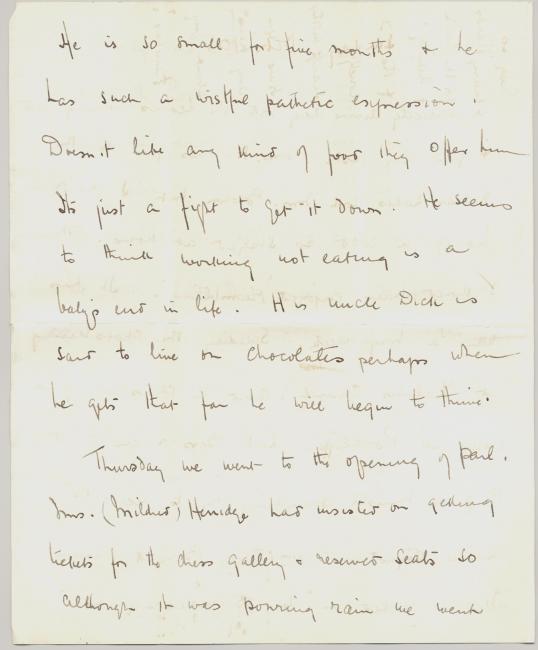

He is so small for five months & he has such a wistful pathetic expression. Doesn’t like any kind of food they offer him. It’s just a fight to get it down. He seems to think working not eating is a baby’s end in life. His uncle Dick is said to live on chocolates perhaps when he gets that far he will begin to thrive.

Thursday we went to the opening of Parl. Mrs. (Mildred) Herridge had insisted on getting tickets for the chess [press] gallery & reserved seats so although it was pouring rain we went

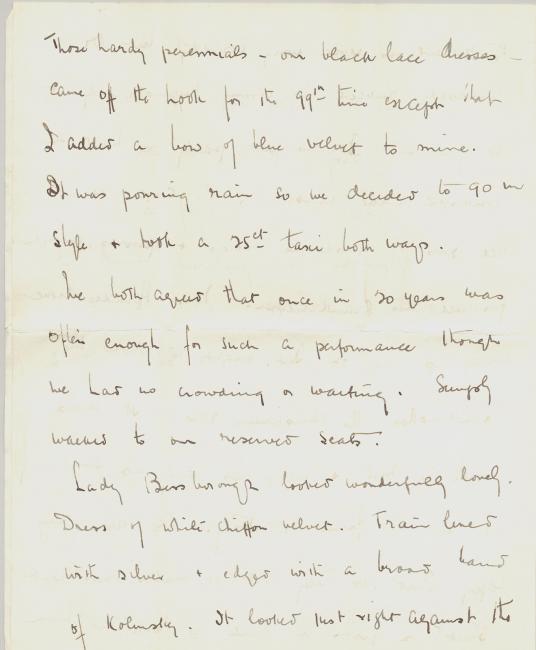

Those hardy perennials—our black lace dresses came off the hook for the 99th time except that I added a bow of blue velvet to mine. It was pouring rain so we decided to go in style & took a 25ct taxi both ways.

We both agreed that once in 20 years was often enough for such a performance though we had no crowding or waiting. Simply walked to our reserved seats.

Lady Bessborough looked wonderfully lovely. Dress of white chiffon velvet. Train lined with silver & edged with a broad band of Kolinsky. It looked just right against the

red carpet & chairs which killed some of the pinks & purples. Mr. Bennett perspired in gold lace & white satin trousers, cocked hat with the same grim determination with which he raises the tariff & cuts down the Civil Service. “My poor darling brother,” Mildred said, on Monday when she was going away. “How will he get into that coat alone.

On Tues. our old friend Mrs. Inderwick came down to the hospital for some Xray treatments & has been here all week. Cyril has been going & coming & Friday night stayed all

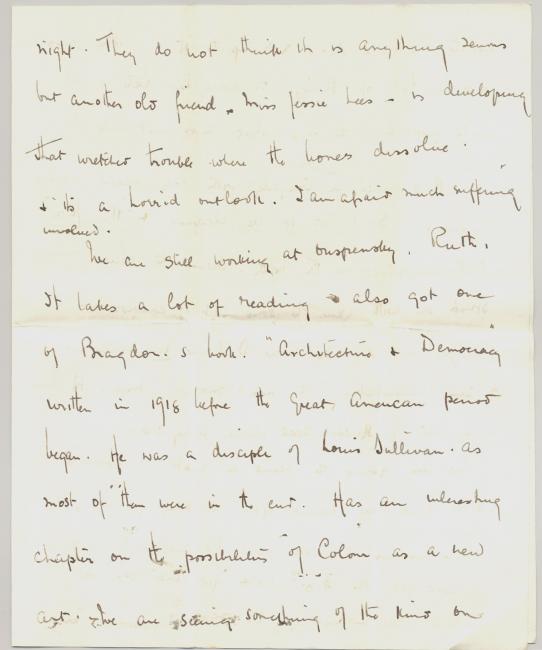

night. They do not think it is anything serious but another old friend — Miss Jessie Lees—is developing that wretched trouble where the bones dissolve & it’s a horrid outlook. I am afraid much suffering involved.

We are still working at Ouspensky. Ruth, it takes a lot of reading also got one of Bragdon’s book. “Architecture & Democracy” written in 1918 before the Great American period began. He was a disciple of Louis Sullivan as most of them were in the end. Has an interesting chapter on the possibilities of Colour as a new art. We are seeing something of the kind on

the stage to-day.

Speaking of the stage, we had a charming letter from Tony Guthrie yesterday. Saying he has a new book coming out and that his play “The Second Coming” will be produced in 6 weeks. We discussed the possibility of going over to see it but decided that even if Tony did give us passes it would come a little high.

Mrs. Herridge isn’t really very well. She seems very tired. As if she were on the verge of a nervous break. We were to have driven to Montreal this week but I persuaded her

not to. I think she’s not up to it. She has had a lot of things to worry her lately but we’ll just have to see what more rest will do.

Had quite a minor tragedy with my green coat, Rufus. Sent it to be cleaned & the “fur” collar dissolved in the bath. Seems to have been stuck on with glue to some sort of composition & the glue melted. So now I have no collar & am meditating the next move. Mrs. H. has some bits of Hudson seal which may DO.

We are going to send a list of books soon that we want you to buy for us. Am anxious to hear how the curtains look. Haven’t got the $8.00 back yet but they say I will. Does mother enjoy the park?

Love.

M

MB Williams to her family, 16 November 1931

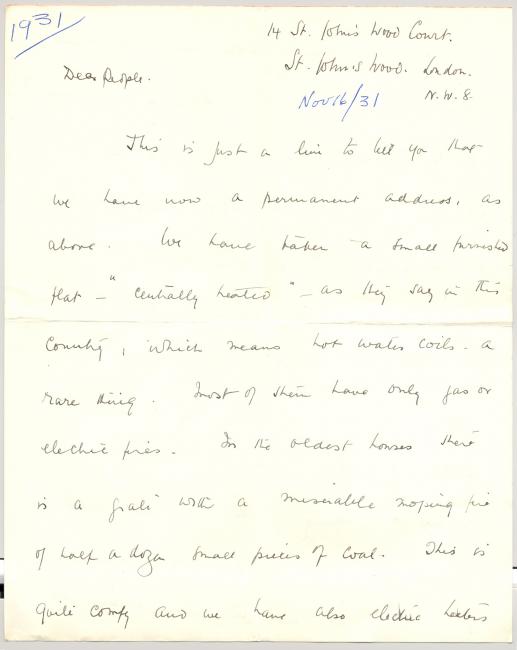

1931

14 St. John’s Wood Court.

St. John’s Wood. London.

N.W.8.

Nov 16/1931

Dear People.

This is just a line to tell you that we have now a permanent address, as above. We have taken a small furnished flat—“centrally heated” as they say in this country, which means hot water coils, a rare thing. Most of them have only gas or electric fires. In the oldest houses there is a grate with a miserable moping fire of half a dozen small pieces of coal. This is quite comfy and we have also electric heaters

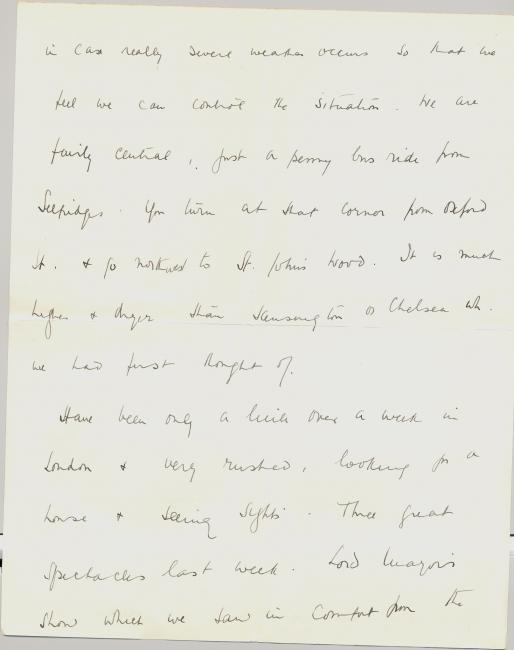

in case really severe weather occurs so that we feel we can control the situation. We are fairly central, just a penny bus ride from Selfridges. You turn at that corner from Oxford St. & go northwest to St. John’s Wood. It is much higher and dryer than Kensington or Chelsea wh. We had first thought of.

Have been only a little over a week in London & very rushed, looking for a house & seeing sights. Three great spectacles last week. Lord Mayor’s show which we saw in comfort from the

windows of the Palace Strand Hotel where we were staying—a wonderful place where you get room & breakfast, bath, books & general service for $2.25 per day. No tips. The Lord Mayor looked very important in his ancient gold coach but the show was somewhat spoiled by a downpour of rain. However London crowds don’t mind that & the streets were lined with a six-deep thicket of umbrellas for hours before. The procession was about a mile long & was something after the order of our Labour Day affairs. Floats showing the progress of industry etc. first bicycle, & motor car old

horse omnibus etc. Then the beef-eaters from the Tower.

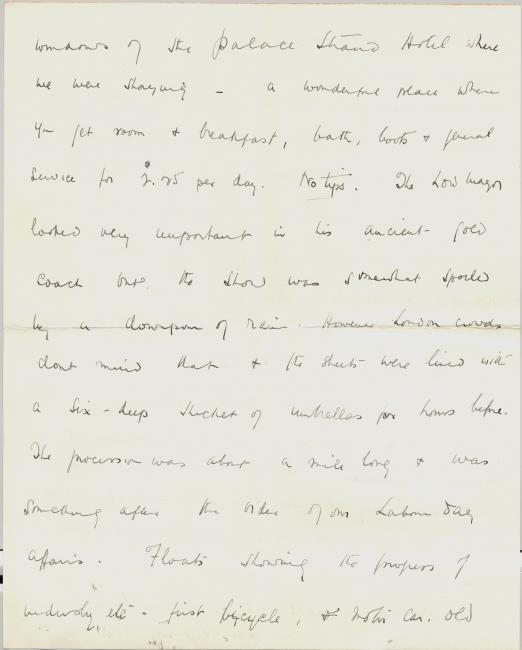

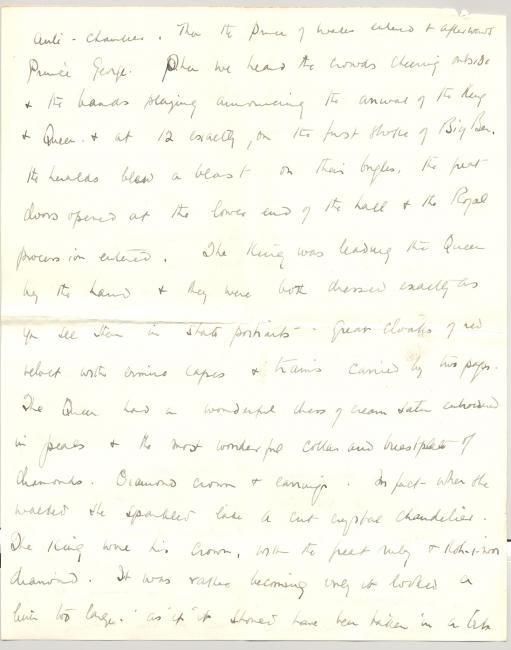

Tues we went to the opening of Parl. Bill Herridge had written to Col Vannier, who is the real head of the High Commissioners office & he is simply turning the office on end to get us into things. There is of course a great demand for tickets but he managed at the last moment to get us two for the Royal Gallery. That is a long gallery opening out from behind the Throne through which the King & Queen pass. We saw the peers & peeresses come in in gold lace & diamonds & all the processional ceremony. Imagine a long Gothic hall with tiers of seats rising at each side (where we were) Royal blue carpet rolled down for the occasion. The crown & orb in position, Beaf-eaters, heralds & kings chamberlains all drawn up at each side of the open way. At 10 min to 12 the Crown was solemnly borne into the

anti-chamber. Then the Prince of Wales entered & afterwards Prince George. Then we heard the crowds cheering outside & the bands playing announcing the arrival of the King & Queen & at 12 exactly, on the first stroke of Big Ben the heralds blew a blast on their bugles. The great doors opened at the lower end of the hall & the Royal procession entered. The King was leading the Queen by the hand & they were both dressed exactly as you see them in the state portraits. Great cloaks of red velvet with ermine capes & trains carried by two pages. The Queen had a wonderful dress of cream satin embroidered in pearls & the most wonderful collar and breast plate of diamonds. Diamond crown & earrings. In fact—when she walked she sparkled like a cut crystal chandelier. The King wore his crown, with the great ruby & Koh-i-noor diamond. It was rather becoming only it looked a little too large as if it should have been taken in a bit.

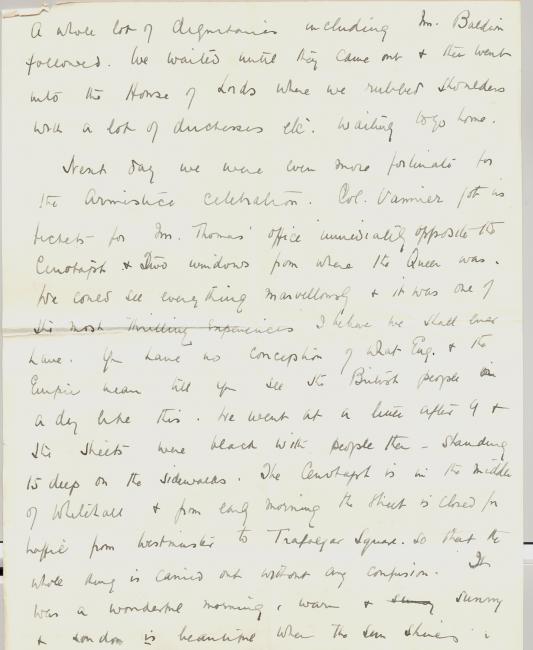

A whole lot of dignitaries including M. Baldwin followed. We waited until they came out & then went into the House of Lords where we rubbed shoulders with a lot of duchesses etc. waiting to go home.

Next day we were even more fortunate for the Armistice Celebration. Col. Vannier got us tickets for M. Thomas’ office immediately opposite the Cenotaph & two windows from where the Queen was. We could see everything marvellously & it was one of most thrilling experiences I believe we shall ever have. You have no conception of what Eng. & the Empire mean till you see the British people on a day like this. We went at a little after 9 & the streets were black with people then—standing 15 deep on the sidewalks. The Cenotaph is in the middle of Whitehall & from early morning the street is closed for traffic from Westminster to Trafalgar Square so that the whole thing is carried out without any confusion. It was a wonderful morning, warm & sunny & London is beautiful when the sun shines.

About 10 we went out on to the balconies & Lady Williams Taylor of Montreal happened to stand next to us & as she had seen it many times before she was able to tell us just what was going on. You can see from the pictures just how it looked. At 10.50 the Prince came out of the Home offices & took his place & the Cabinet Ministers etc. The bishop, choir & about 10 bands were already in place. At 10.55 he stepped forward, bowed & laid his wreath at the foot of the Cenotaph. Then Mr. MacDonald, Mr. Baldwin, and Mr. Ferguson & the representatives of the Dominions laid theirs & the Bishop of London said a prayer. At 11 the bells rang out all over the city. The flags dipped & then there was absolute silence for 2 min. The motor buses stopped & the people got out took off their hats & waited. You can’t imagine how thrilling it was. Then the bishop prayed again & the Grenadier [freands] Band played almost in a whisper the first bars of God Save the King. You realized that that was what the whole thing meant.

It was tremendous. The tears simply ran down our faces.

Thurs. we went to Col Vanniers to lunch & had a lovely time. Going out for three other engagements this week so we shall soon know people.

Hope to write oftener now.

No word from you yet but Blanche has just phoned to say there are letters here which I hope may be from you.

Best love to you all

M. B.

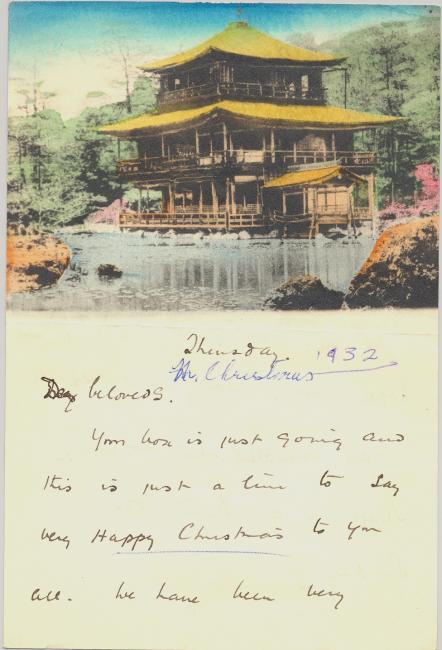

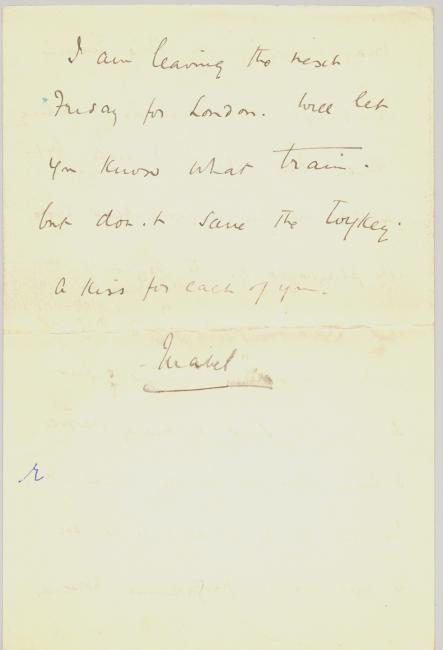

MB Williams to her family, December 1932

[Japanese scene in colour on top]

Thursday 1932

M. Christmas

Dear beloveds.

Your box is just going and this is just a time to say very Happy Christmas to you all. We have been very

busy working on this Empire broadcast for Christmas morning which Mrs. H. & I wrote but to-day we feel a good deal like the playwright on the night of a first production. For our original has been trimmed & cut so often to suit so many people & times that we hardly know it. We are quite thrilled to be on the first historic programme however

though it doesn’t mean any money this time.

I hope your little gifts will have some attractions. They go with much love.

We are both quite well & happy though Dolly had her bumper smashed this morning. Shall be at Perth on Sunday.

I am leaving the next Friday for London. Will let you know what train but don’t save the turkey.

A kiss for each of you.

Mabel

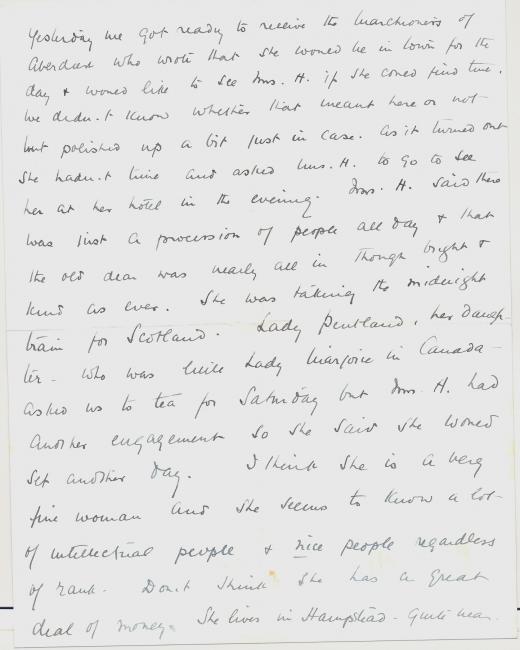

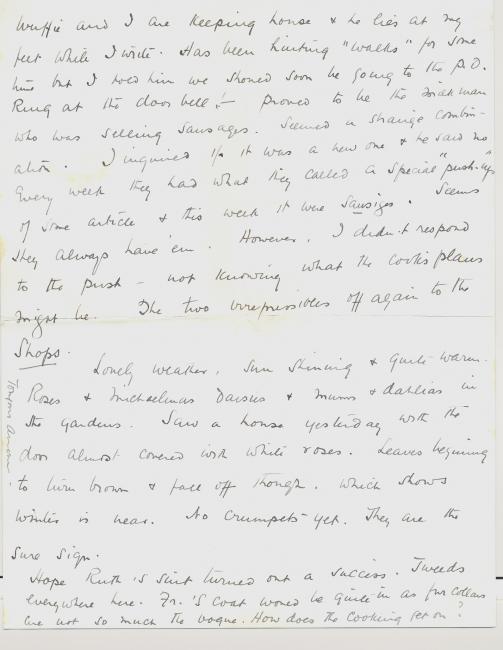

MB Williams to her family, 18 October 1933

2 Golder’s Court.

Woodstock Rd

Golder’s Green. N.W.II. London.

Oct. 18.

Dear Everybody,

The “Empress” is due to-night and I expect there will be letters from you to-morrow but I find that mine have to be posted to night or early to morrow to be sure of catching her or her return trip. The mail closes at the City P.O. to-morrow at 5 but as we are a good way out we have to allow an extra half-day. I am afraid she won’t be making many more trips. Then we shall have to watch for the fast N.Y. boats, the Canadian lines are so slow.

Been having a very quiet week since our return from Norwich. Chiefly concerned with clothes. I brought over my old green coat (3 yrs) & am having it taken in a little & touched up. It will do very well to fill in. Blanche knows a woman who is a wholesale milliner. I think they rented rooms from her when they first came over and she took us to several wholesales. I want to get a warm dress that will do to go out to lunch in. We went to one very swanky place where they

sell sports models from France and Switzerland. Saw one I liked in raisin colour but as it was $30.00 & didn’t quite fit, I resisted. Blanche is still looking but I gave up. They have promised to report any “finds” & save me the fag.

Everyone here talking about the Disarmament situation and very interesting talks over the Radio. There is a growing feeling that Germany is not to be trusted. That she is really preparing for war and glorifying war by propaganda all the time. France is undoubtedly uneasy and it may be with good cause. I expect she has led the British ministers to think it would be folly to give in to Germany’s demands—because everyone says that until lately British sympathy with Germany had been growing and there was a strong feeling that she should be given more equality. Hitler, however, talks like a madman - the same kind of madness that led to war before. It’s like giving a lunatic a gun to play with.

Yesterday we got ready to receive the Marchioness of Aberdeen who wrote that she would be in town for the day & would like to see Mrs. H. if she could find time. We didn’t know whether that meant here or not but polished up a bit just in case. As it turned out she hadn’t time and asked Mrs. H. to go to see her at her hotel in the evening. Mrs. H. said there was just a procession of people all day & that the old dear was nearly all in though bright & kind as ever. She was taking the midnight train for Scotland. Lady Pentland, her daughter—who was little Lady Marjorie in Canada—asked us to tea for Saturday but Mrs. H. had another engagement so she said she would set another day. I think she is a very fine woman and she seems to know a lot of intellectual people & nice people regardless of rank. Don’t think she has a great deal of money. She lives in Hampstead quite near.

Wuffie and I are keeping house & he lies at my feet while I write. Has been hinting “walks” for some time but I told him we should soon be going to the P.O. Ring at the door bell! Proved to be the milkman who was selling sausages. Seemed a strange combination. I inquired if it was a new one & he said no. Every week they had what they called a special “push-up” of some article & this week it were sausages. Seems they always have’em. However, I didn’t respond to the push—not knowing what the cook’s plans might be. The two irrepressibles off again to the Shops.

Lovely weather, sun shining & quite warm. Roses & Michaelmas daisies & mums & dahlias in the gardens. Saw a house yesterday with the door almost covered with white roses. Leaves beginning to turn brown & fall off though, which shows winter is near. No crumpets—yet. They are the sure sign.

Hope Ruth’s suit turned out a success. Tweeds everywhere here. Fr.’s coat would be quite in as fur collars are not so much the vogue. How does the cooking get on?

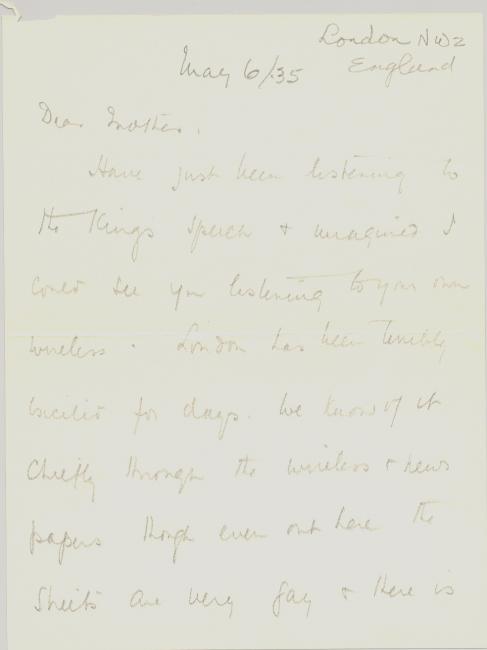

MB Williams to her mother, 6 May 1935

London NW2

England

May 6/35

Dear Mother,

Have just been listening to the Kings speech & imagined I could see you listening to your own wireless. London has been terribly excited for days. We know of it chiefly through the wireless & news papers. Though even out here the streets are very gay & there is

an arch at the top of our street. It’s been the most perfect day like an early June day at home-really King’s weather. Just been listening to Rudyard Kipling who evidently thinks we should stop talking of peace & get ready for war. Europe still seems to have hydrophobia, but it would be dreadful to think of another war.

I am getting stronger every day. Go up on the roof & sit in the sun now. Almost as good as a country house. We can see for miles—over city roofs.

Suppose you are watching for E’s return now. What a lot he will have to tell you. It will take all summer. I hear you have been “going out” with another young man just like you but I hope you make

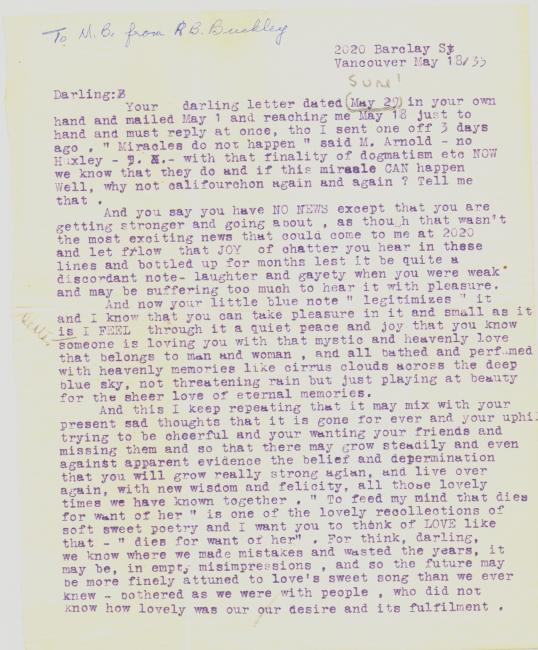

In one letter, we hear that Williams and Herridge’s good friend Charlotte Whitton, the mayor of Ottawa (the first female mayor in Canada), had visited them “fresh from an exciting tête-a-tête with H.R.H. the Pr. of Wales. I don’t know whether this will start a new news story — ‘P of W. to marry a Canadian’ — or not.” Considering that Whitton had a longtime female companion, and there has been longtime debate whether they were lesbians, it is hard to know whether MB wrote this tongue in cheek. Of course, MB had a longtime female companion of her own. In part for that reason, two of the most compelling items here are love letters to and from Canadian journalist and one-time Parks Branch staffer Alfred B. Buckley, in which the two speak passionately of wasted years and might-have-beens. We learn much about Williams’s life from her correspondence, but we do not learn everything.

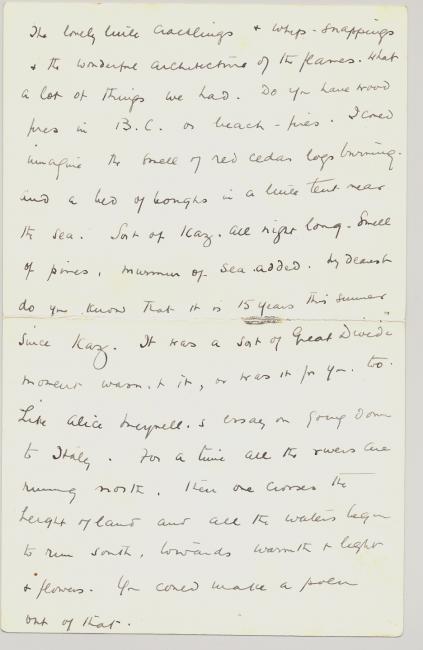

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document. It features handwritten letters from Alfred B. Buckley to MB Williams and from MB Williams to Mr. Buckley to her family between 1935 and 1936.

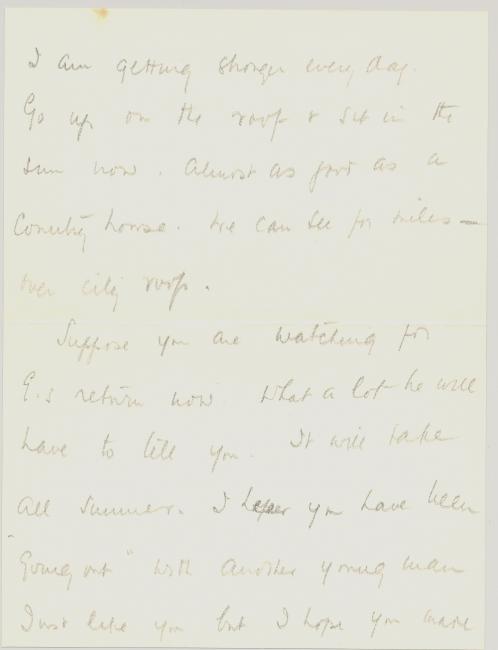

A. B. Buckley to MB Williams, 18 May 1935

[Handwritten] To M.B. from A. B. Buckley

[Remainder typed]

2020 Barclay St.

Vancouver May 18/35

Darling: B

Your darling letter dated (May 29/June 1) in your own hand and mailed May 1 and reaching me May 18 just to hand and must reply at once, tho I sent one off 3 days ago, “Miracles do not happen” said M. Arnold—no Huxley—

with that finality of dogmatism etc NOW we know that they do and if this miracle CAN happen. Well, why not califourchon again and again? Tell me that.

And you say you have NO NEWS except that you are getting stronger and going about, as though that wasn’t the most exciting news that could come to me at 2020 and let flow that JOY of chatter you hear in these lines bottled up for months lest it be quite a discordant note - laughter and gayety when you were weak and may be suffering too much to hear it with pleasure.

And now your little blue note “legitimizes” it and I know that you can take pleasure in it and small as it is I FEEL through it a quiet peace and joy that you know someone is loving you with that mystic and heavenly love that belongs to man and woman, and all bathed and perfumed with heavenly memories like cirrus clouds across the deep blue sky, not threatening rain but just playing at beauty for the sheer love of eternal memories.

And this I keep repeating that it may mix with your present sad thoughts that it is gone for ever and your uphill trying to be cheerful and your wanting your friends and missing them and so that there may grow steadily and even against apparent evidence the belief and determination that you will grow really strong again, and live over again, with new wisdom and felicity, all those lovely times we have known together. “To feed my mind that dies for want of her” is one of the lovely recollections of soft sweet poetry and I want you to think of LOVE like that—“dies for want of her.” For think, darling, we know where we made mistakes and wasted the years, it may be, in empty misimpressions, and so the future may be more finely attuned to love’s sweet song than we ever knew—bothered as we were with people, who did not know how lovely was our our desire and its fulfilment.

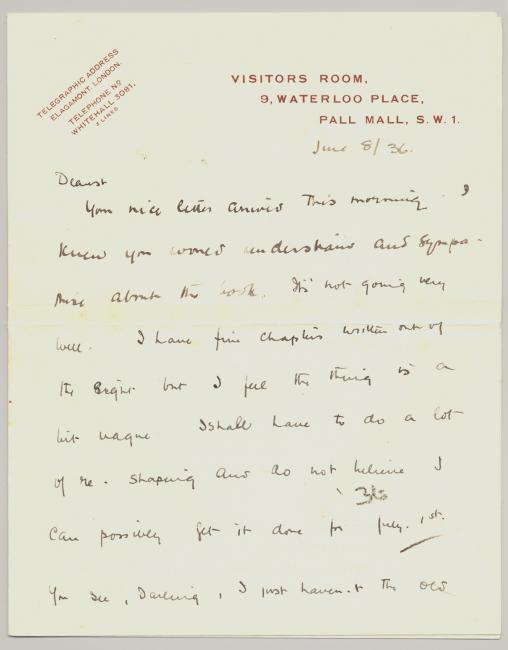

MB Williams to A. B. Buckley, 8 June 1936

[Letterhead]

Telegraphic Address

Elagamont, London

3 lines

Telephone No.

Whitehall 3081

Visitors Room,

9, Waterloo Place,

Pall Mall, S.W.1.

June 8/36.

Dearest

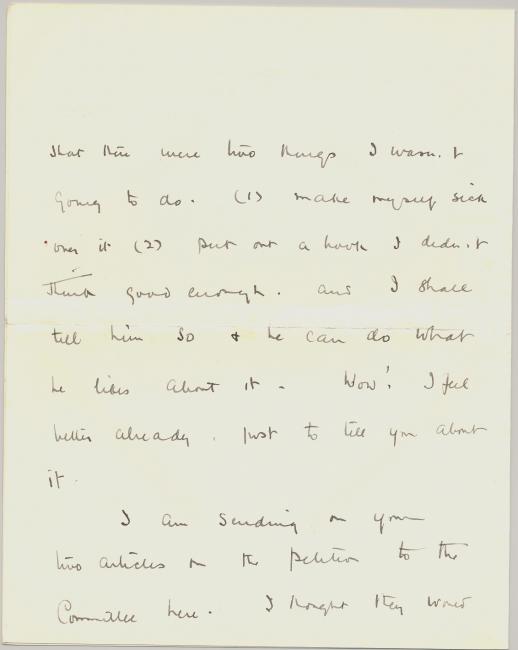

Your nice letter arrived this morning. I knew you would understand and sympathise about the book. It’s not going very well. I have five chapters written out of the eight but I feel the thing is a bit vague. I shall have to do a lot of re-shaping and as not believe I can possibly get it done for July 1st. You see, darling, I just haven’t the old

capacity to work long hours at a stretch. Really I should only work in the mornings and play in the afternoons. Go off in Baberts and lie on a hillside and listen to the waterfalls falling and the bumblebees buzzing & perhaps flirt a bit with a nice man—I have been trying to work all day & it just won’t do. So I have decided to ask the publisher for another month. If he won’t allow it, well I’m sorry but I made up my mind to-day

that there were two things I wasn’t going to do. (1) make myself sick over it (2) put out a book I didn’t think good enough and I shall tell him so & he can do what he likes about it. Wow! I feel better already. Just to tell you about it.

I am sending on your two articles & the petition to the Committee here. I thought they would

like to know about it.

I am afraid to have you send the Biron, Dearest, because I don’t know about the English law. Wait till I have more leisure then I’ll make enquiries here.

Nice to feel your dear & helpful sympathy – that is a very wonderful thing. A little ‘wind of kisses’ now & then would help, too, but I get them even through the cold paper, & the little bird’s feather that comes from the nest in Kaz. What a memory to have. It’s marvelous to have done a thing like that. It means something for eternity, somewhere. [Pen]

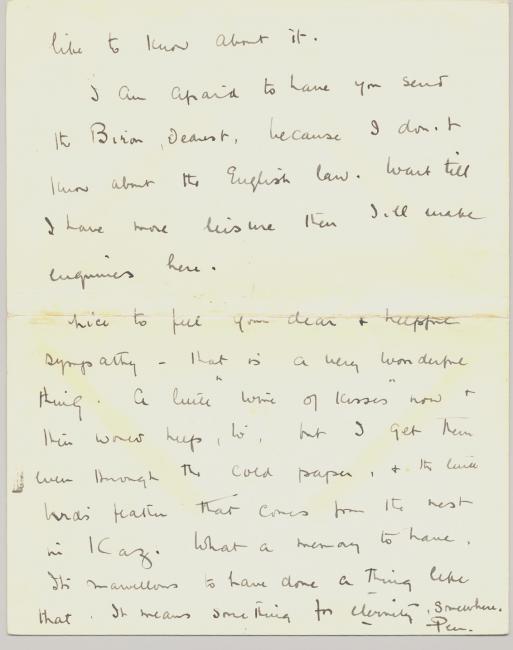

I have just got to know some members of a group who are working for betterment here. Such a nice man, who is the editor of an “Animals Welfare” paper, but a complete cripple. We had a good talk & he wants me to do some writing for him & to speak at a conference on Nat’l Parks—wild life conservation in Canada. But he is interested in the social movement too. If you will send me the date of that extract from the Bankers Mag. I will get him to publish it widely over here. I’ll write for the Ang. Cath. Pamphlets & other things you mention. Am sending you Vernon Bartlett’s new magazine The World Review of Reviews. It gives a good resumé of the international situation from the eyes of the other nations who don’t regard England with quite the lofty approval she accords herself.

Your last budget of “columns” was very hot stuff. Sometimes I am almost afraid somebody will knock you on the head or

run you into jail. You are absolutely fearless but I suppose you know how to circumvent the Libel Law. R.B.B. would enjoy sticking a little knife into you. I am sure. But it’s simply splendid, darling, to see how busy & useful you are. It’s a big responsibility too, just now, shaping public opinion.

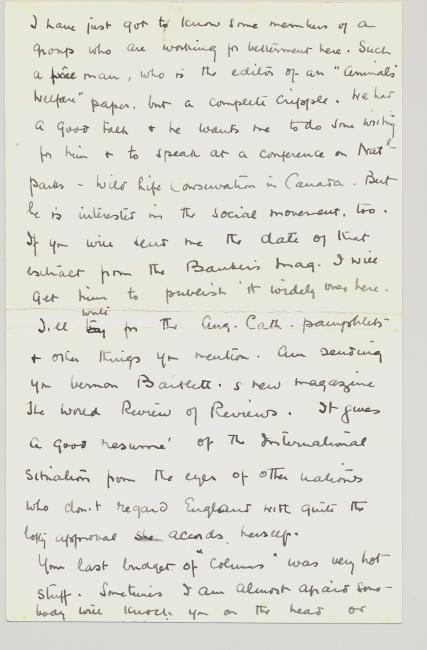

As you say, a great deal of the best thought over here is moving to socialism. I am told Oxford is strongly socialistic & so secretly is the King. Someone who is very well informed told me he didn’t want the crown at all but was only persuaded to take it because he was made to see he could really do more as king than any other way. But he complained it wasn’t a man’s job. (This isn’t for publication) but it may be true, & if so, it’s good.

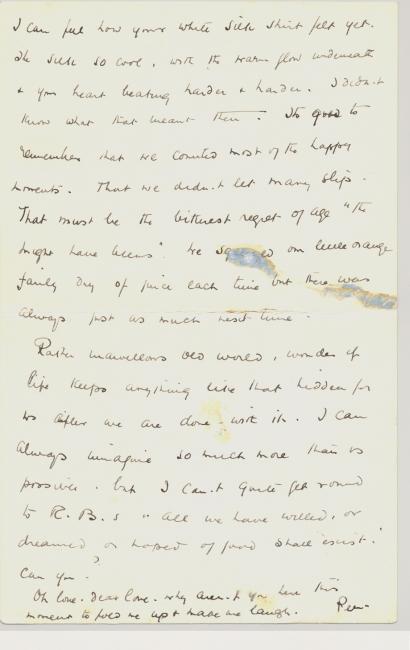

Yes, I saw after I wrote you, that you had changed the Burglary play

but the whole thing is coming more & more unstuck every day.

Here is a nice little bit about the king for that little play you spoke of. An M.P. tells the story in the last Nash’s Mag. He said he took him through the unemployed areas [lanon] & the Clyde, before the last election & what the king said about the housing conditions was almost too strong to print. One Conservative organizer remarked, “Every time that fellow opens his mouth he loses us 100,000 votes.” In a few weeks the king (then P. of W.) wanted to make another trip to the north. Influence was brought to bear to dissuade him but he would go. So the powers decided the next best thing would be to keep the visit as quiet as possible. Not let the press know. However the P. of W. heard of this & he deliberately gave the

visit as much publicity as possible & personally arranged that all the press men should be there to take down everything he said about the conditions.

It’s a new era when a reigning sovereign refuses not only a private train but even a private coach & travels down to Sandringham in a 1st class carriage (reserved) carrying his own dispatch case. Looks a bit nearer to Plato’s philosopher king.

All this for chit-chat by the fire, dearest. While we are “warming up.” Time now to slip into silk & relax & lie back & look at the fire together. The world well-lost. Ah! Those pine knot fires! What a lovely thing they were in themselves. One could write a poem about pine-knots.

The lovely little cracklings & whip snappings & the wonderful architecture of the flames. What a lot of things we had. Do you have wood fires in B.C. or beach-fires. I could imagine the smell of red cedar logs burning and a bed of boughs in a little tent near the sea. Sort of Kaz. all night long. Smell of pines, murmur of sea added. My dearest do you know that it is 15 years this summer since Kaz. It was a sort of Great Divide moreover wasn’t it, or was it for you too. Like Alice Meynell’s essay on going down to Italy. For a time all the rivers are running north. Then one crosses the height of land and all the waters began to run south, towards warmth & light and flowers. You could make a poem out of that.

I can feel how your white silk shirt felt yet. The silk so cool, with the warm flow underneath & your heart beating harder & harder. I didn’t know what that meant then. It’s good to remember that we counted most of the happy moments. That we didn’t let many slip. That must be the bitterest regret of all “the might have beens.” We squeezed our little orange family dry of juice each time but there was always just as much next time.

Rather marvellous old world, wonder if life keeps anything like that hidden for us after we are done with it. I can always imagine so much more than is possible but I can’t quite get around to R.B.’s [[Browning’s]] “all we have willed, or dreamed or hoped of good shall exist.” Can you?

Oh love, dear love, why aren’t you here this moment to hold me up & make me laugh.

[Pen]

Many of MB’s letters from this period are to her niece, “Rufus” (Ruth). In a February 1934 letter, she responds to a question as to whether modern life is bad for women. Rather than answering directly, she tells of having recently read John Cowper Powys’s A Philosophy of Solitude (she gets the name wrong). She writes of the differences between extroverts who experience things outside themselves and introverts who experience within—and that everyone who has experienced both knows the inner seems somehow more real. Williams in the early 1930s was still very active, but more so than in previous decades she was watching the world go by—and seemed at peace with that. Her answer to Rufus seems to be that modern life gives women some opportunities to cultivate the inner self. She then tells Rufus to get Powys’s book and see what she thinks for herself.

A selection of letters are given in this chapter, but you can peruse the entire collection of MB Williams’s correspondence in the collection.