Lithograph of two male Paradise Parrots by H. C. Richter illustrated the species in John Gould’s The Birds of Australia, 1848.

Lithograph of two male Paradise Parrots by H. C. Richter illustrated the species in John Gould’s The Birds of Australia, 1848.

Originally John Gould, The Birds of Australia, vol. 5, London, 1848. View source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

“The Paradise Parrot Tragedy” was the final chapter of Alec Chisholm’s book, Mateship with Birds, published in 1922. For the preceding two decades, the Paradise Parrot (Psephotellus pulcherrimus) was widely feared to be extinct, but before Chisholm finished writing his book there was news to the contrary. On 11 December 1921, a grazier named Cyril Jerrard found a pair of Paradise Parrots on his property near Gayndah, about 300 kilometers northwest of Brisbane, Australia. The rediscovery proved that the species had not fallen into extinction, but scanty numbers showed equally clearly that it hovered on the brink. That was the tenor of Chisholm’s chapter on “The Paradise Parrot Tragedy.”

“The extinction of a species is a ghastly thing,” Chisholm warned, but it was looming alarmingly close for many species of Australia’s birds. For him, the Paradise Parrot’s near brush with annihilation provided a cautionary tale to which his fellow Australians must pay heed. In the lavish language then fashionable among nature writers, he concluded Mateship with Birds by urging readers to “dispute the dangerous idea that a thing of beauty is a joy for ever in a cage or cabinet; and disdain, too, the lopsided belief that the moving finger of Civilisation must move on over the bodies of ‘the loveliest and the best’ of Nature’s children.”

When Chisholm wrote those words in 1922, he could not have known how deep the tragedy of the Paradise Parrot would run. The species had just been rediscovered. Chisholm himself, guided by Jerrard, saw a pair of the parrots later in 1922. But that was among the last sightings ever.

Cyril Jerrard inspecting an abandoned Paradise Parrot nest in a termite mound near his property in the Gayndah district, 1922. In the background can be seen the sparsely timbered grassland which was the species’ preferred habitat—and, to the parrot’s misfortune, the environment sought by cattle graziers.

Cyril Jerrard inspecting an abandoned Paradise Parrot nest in a termite mound near his property in the Gayndah district, 1922. In the background can be seen the sparsely timbered grassland which was the species’ preferred habitat—and, to the parrot’s misfortune, the environment sought by cattle graziers.

Unknown photographer, 1922. Courtesy of Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, PXA 1772, box 6.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Individuals and pairs of the species were seen sporadically in the Gayndah district over the course of the 1920s. There are a few reliable records of sightings in nearby areas in the 1930s and early 1940s. After that come only rumor, hope, and unsubstantiated claim. Today, the Paradise Parrot has the lamentable status of being the only mainland Australian bird species listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as extinct.

A pair of Paradise Parrots on the termite mound in which they built their nest. The practice of nesting in termite mounds is shared with a closely related species, the endangered Golden-shouldered Parrot (Psephotellus chrysopterygius). As is the case for that species, it probably made the Paradise Parrot exceptionally vulnerable to the environmental changes wrought by pastoralism.

A pair of Paradise Parrots on the termite mound in which they built their nest. The practice of nesting in termite mounds is shared with a closely related species, the endangered Golden-shouldered Parrot (Psephotellus chrysopterygius). As is the case for that species, it probably made the Paradise Parrot exceptionally vulnerable to the environmental changes wrought by pastoralism.

Photograph by Cyril Jerrard. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, PIC/8902/1 LOC Box PIC/8902.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Even before he saw the birds, Chisholm understood the main causes of their decline: inappropriate burning of grasslands after the advent of pastoralism in the parrot’s habitat, the ravages of feral cats, and excessive trapping for the aviary trade (as its name implies, the Paradise Parrot was an exquisitely beautiful bird, highly prized by aviculturists). These are the factors cited by ecologists today to explain the species’ demise, although now they are framed in more scientifically sophisticated terms and tend to emphasize the environmental impacts of the changed fire regimes consequent upon Aboriginal dispossession. Yet while Chisholm had a reasonable grasp of the factors impelling extinction, he and his ornithological contemporaries did not know how to stop it. As historian Mark Barrow explains, a paucity of effective scientific strategies to save endangered species was a worldwide problem in the interwar years.

Nonetheless, Chisholm did what he could to save the Paradise Parrot. In early 1922, he and Jerrard planned an attempt at captive breeding for intended release back into the wild. It was an early instance of this procedure in Australia but was aborted when that year’s clutch of eggs failed to hatch. As a campaigner for conservation, Chisholm ensured that Queensland’s Animals and Birds Act 1921 offered protection to the Paradise Parrot. But he and his birding colleagues knew that legal protection alone could not save a species.

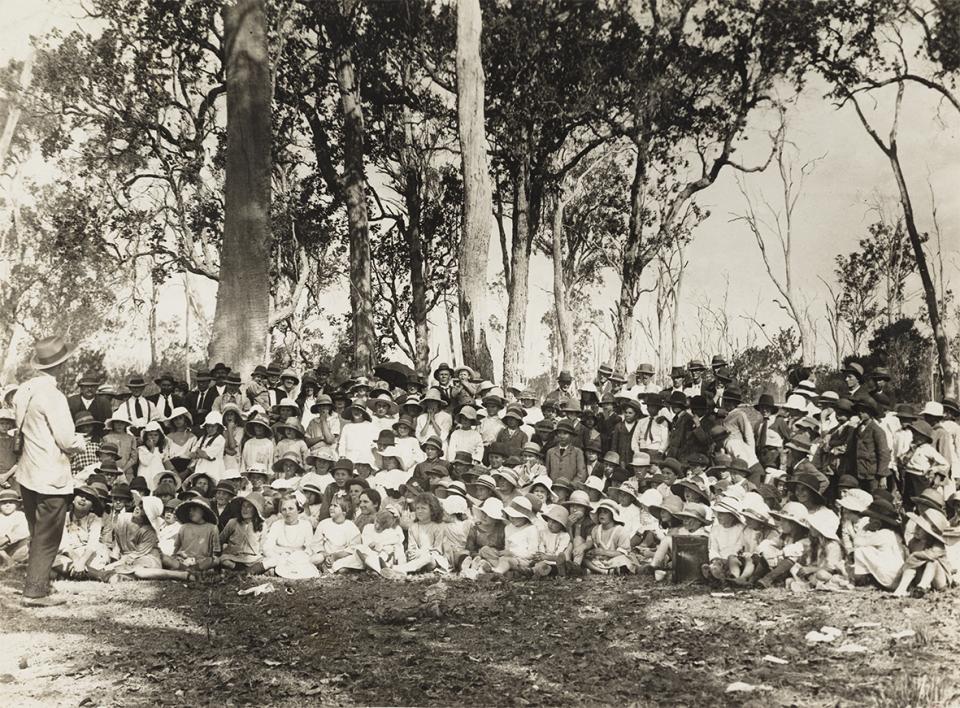

Alec Chisholm (far left) at Goomeri, a small town near Gayndah, addressing school children and their parents on the need for conservation, 1921. Chisholm was a prolific propagandist for the conservationist cause.

Alec Chisholm (far left) at Goomeri, a small town near Gayndah, addressing school children and their parents on the need for conservation, 1921. Chisholm was a prolific propagandist for the conservationist cause.

Unknown photographer, 1921.

Courtesy of Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Collection PXA 1772, box 6.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

It was by appealing to the public conscience that Chisholm mounted his major attempts to save the Paradise Parrot. A journalist by profession, his conservation advocacy, like that of many others at the time, was emotive, with strong aesthetic and nationalist strands.

“The Paradise Parrot Tragedy” was only one of numerous works in which he publicized the species’ plight and pleaded for its preservation. He ended a contemporaneous newspaper article with a characteristically emotive plea:

The next move in the history of the paradise parrots rests with the people of Queensland. It is for them to say if “the most beautiful parrot that exists” shall be wiped off the face of the earth. The governing authorities of the State have done their part—or at least done something—by according the lovely birds the total protection of the law; but this cannot be made effective unless Queenslanders are patriotic enough to say: “This slaughter of the Innocents has gone far enough.”

—Alec Chisholm

The first-ever photograph of a Paradise Parrot: a male at the entrance to its nest in a termite mound, taken by Cyril Jerrard in March 1922. Only four or five photographs were ever taken of the species in the wild. All were by Jerrard.

The first-ever photograph of a Paradise Parrot: a male at the entrance to its nest in a termite mound, taken by Cyril Jerrard in March 1922. Only four or five photographs were ever taken of the species in the wild. All were by Jerrard.

Photograph by Cyril Jerrard. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, PIC/ 8902/3 LOC Box PIC/8902.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

It’s flowery writing by today’s standards, but as environmental historian Dolly Jørgensen reminds us, mobilizing emotions has always been crucial in efforts to save endangered species.

In a highly critical account of Chisholm’s dealings with the Paradise Parrot, ecologist Penny Olsen dismisses his efforts as mere “words,” lacking substantiation in “action.” It is an inapt accusation, for conservation has always depended as much on communication as on physical strategies to promote survival. To preserve endangered species, wielding words is an essential form of action.

Chisholm failed to avert the tragedy of the Paradise Parrot, though not for want of trying. The emotive appeals he launched did not exactly fall on deaf ears, but they were an insufficient counter to a social ethos that valued economic gain over avian loss. Beyond that was the problem that contemporary science did not offer an adequate repertoire of strategies to save endangered species. The latter problem has been substantially remedied today. The former—prioritizing economic gain over avian loss—remains more stubborn.

How to cite

McGregor, Russell. “The Tragedy of the Paradise Parrot.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2021), no. 27. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9340

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Russell McGregor

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Barrow, Mark. Nature's Ghosts. Confronting Extinction from the Age of Jefferson to the Age of Ecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Chisholm, Alec. Mateship with Birds. Melbourne: Whitcombe & Tombs, 1922.

- Jørgensen, Dolly. Recovering Lost Species in the Modern Age: Histories of Longing and Belonging. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2019.

- McGregor, Russell. “Alec Chisholm and the Extinction of the Paradise Parrot.” Historical Records of Australian Science 32, no. 2 (2021): 156–167. doi:10.1071/HR20019

- McGregor, Russell. Idling in Green Places: A Life of Alec Chisholm. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2019.

- Meine, Curt. “De-Extinction and the Community of Being.” The Hastings Center Report 47, no. 4 (2017): S9–S17. doi:10.1002/HAST.746

- Olsen, Penny. Glimpses of Paradise: The Quest for the Beautiful Parrakeet. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2007.