Machland floodplain during a minor flood 2009.

Machland floodplain during a minor flood 2009.

Friedrich Fürlinger, Wallsee, Lower Austria, 2009.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Prior to regulation the Danube was a highly dynamic river. Floods occurred regularly as part of the river’s normal behaviour. With every flood the water changed its course, winter ice floods were particularly abrasive. The river froze regularly, and in one notably cold winter, 1876, the Danube was frozen from Tulln to Budapest (380 km) throughout all of February. Ship transport suffered from the frequent changes of the river bed.

Where did ships move through the Machland at which time?

Where did ships move through the Machland at which time?

Locations of the downstream waterways since the late 17th century

All rights reserved © 2010 Severin Hohensinner

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

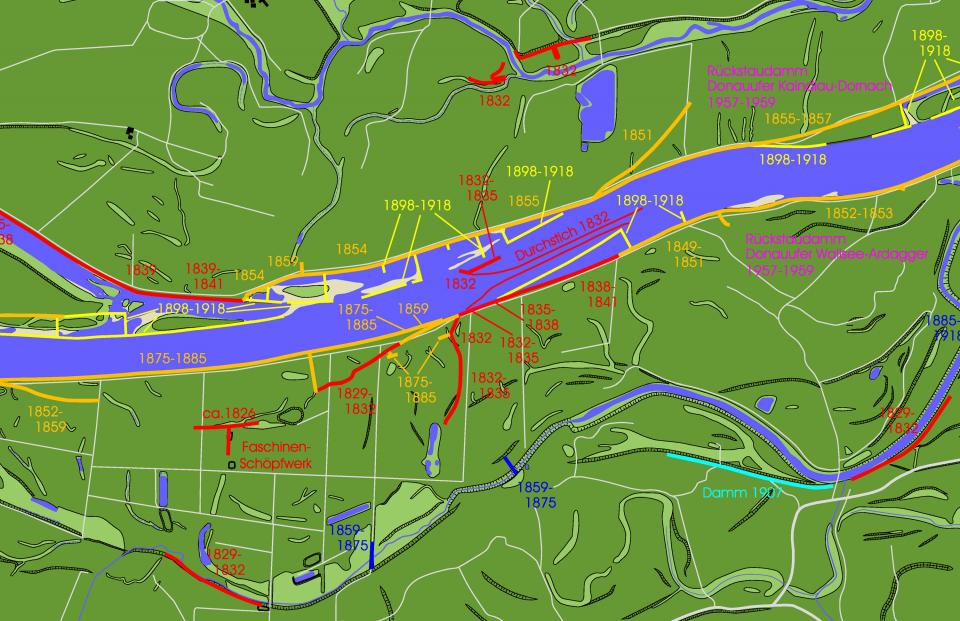

Regulation efforts in the Machland, an alluvial floodplain of the Austrian Danube, started as early as 1826. These efforts were triggered by the danger that the meandering river—with its maze of shallow channels, islands and gravel bars—presented to ships. The main channel moved continuously to the south, so this channel was blocked and a diversion dam was built to direct all water to the northern fork. While the plan worked, the increased flow of water threatened to erode the northern bank. In response, an artificial channel was dug right through Weidenhaufen Island in 1832. As planned, the river widened its new channel. This resulted in a straightened shipping route. However, as an unintended consequence, the freshly eroded sediment was deposited right after the outlet of the channel, making navigation in the so-called Holler more difficult than before.

The only solution to the problem was to stabilize the banks over several kilometres with training works. Eventually, after 35 years of planning and building dykes, groynes and training works, the regulation was “complete”—the river was tamed.

Danube in Machland (1829)

Danube in Machland (1829)

The Machland prior to the excavation of the shipping channel trough the Weidenhaufen Island in 1829.

All rights reserved © 2008 Severin Hohensinner

Grant sponsor: FWF-project no. P14959-B06

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Danube in Machland (1832)

Danube in Machland (1832)

The Machland after the completion of channel in 1832. Right after the channel, large new deposits have formed a maze of islands.

All rights reserved © 2008 Severin Hohensinner

Grant sponsor: FWF-project no. P14959-B06

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The regulation of the Danube cost 220.000 Gulden per kilometre in the nineteenth century. Taming the waters came at a considerable price, about twice as much as building the same length of railway track.

Regulation works in a small area of the Danube

Regulation works in a small area of the Danube

Regulation works in a small area given with dates on a map of the river landscape of 2010.

All rights reserved © 2010 Severin Hohensinner

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

How to cite

Hohensinner, Severin. “Taming the Danube: Floodplain Regulation in the Machland.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2011), no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/2648.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2011 Severin Hohensinner

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Hohensinner, Severin. Rekonstruktion ursprünglicher Lebensraumverhältnisse der Fluss-Auen-Biozönose der Donau im Machland auf Basis der morphologischen Entwicklung von 1715–1991. PhD diss., University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, 2008. Available to download here [in German with English abstract].

- Hohensinner, Severin. “‘Sobald jedoch der Strom einen anderen Lauf nimmt...’ Der Wandel der Donau vom 18. zum 20. Jahrhundert.” In Umwelt Donau: Eine andere Geschichte, edited by Verena Winiwarter and Martin Schmid, 38–55. St. Pölten: Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv: 2010. Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name, shown at the Pfarrhof in Ardagger Markt.

- Winiwarter, Verena, Martin Schmid, Severin Hohensinner, and Gertrud Haidvogl. “The Environmental History of the Danube River Basin as an Issue of Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research.” In Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research. Studies in Society: Nature Interactions across Spatial and Temporal Scales, edited by Simron J. Singh, Helmut Haberl, Marian Chertow, Michael Mirtl, and Martin Schmid, 103–122. Berlin: Springer, 2012.