“It’s calling right beside me but, there’s absolutely no sign of it!” said celebrated birdsong recordist John Kendrick in 1984. He was straining to see a South Island Kōkako (Callaeas cinereus), a wattlebird endemic to Aotearoa (New Zealand), with a last recognized sighting in 1967. In 2021, a group of trampers picked up flute-y tolls characteristic of this “Grey Ghost.” Even so, this did not convince scientific authorities that a bird existed. The Unusual Bird Reporting Form of The Ornithological Society of New Zealand Records Appraisal Committee leans heavily toward visual descriptions. The South Island Kōkako Trust, currently offering NZ$10,000 for confirming evidence of an alive Kōkako, also stresses photographs, video, and/or visible relics—perhaps a freshly dropped feather.

Photograph of eye-catching sculpture “Ghost of the Huia” by artist Paul Dibble (2010) and plaque in Palmerston North. The plaque seems to indicate that “ghost,” to the artist, refers to human beings’ memories of Huia, to which this moving figure offers a tribute, whereas in his 1954 interview with William J. Phillipps, elder Henare Hamana (Ngāti Awa, English; 1880–1973) defines wairua as a “soul” who would leave a body upon death for another world as distinguished from kēhua, which “is a ghost.” Kēhua, according to Te Aka Māori Dictionary online, designates “spirits that linger on earth after death and haunt the living.”

Photograph of eye-catching sculpture “Ghost of the Huia” by artist Paul Dibble (2010) and plaque in Palmerston North. The plaque seems to indicate that “ghost,” to the artist, refers to human beings’ memories of Huia, to which this moving figure offers a tribute, whereas in his 1954 interview with William J. Phillipps, elder Henare Hamana (Ngāti Awa, English; 1880–1973) defines wairua as a “soul” who would leave a body upon death for another world as distinguished from kēhua, which “is a ghost.” Kēhua, according to Te Aka Māori Dictionary online, designates “spirits that linger on earth after death and haunt the living.”

© 2017 Michael Roche. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Privileging eye over ear, along with a materialistic gaze, in searches for last members of a species, enacts an epistemic violence that finalizes extinction—as silenced bones and feathers—as a tick on a timeline. These objectifying terms sound different than Māori whakapapa (genealogy)—relating visible and invisible beings—announced in the Te Ao Tūroa (Māori Natural History Gallery) in Auckland. Disconnecting the living and dead sounds incommensurable with an age-old Māori tauparapara (incantation) that sings of bird voice lacing the ancient worlds of the living and of those passed on.

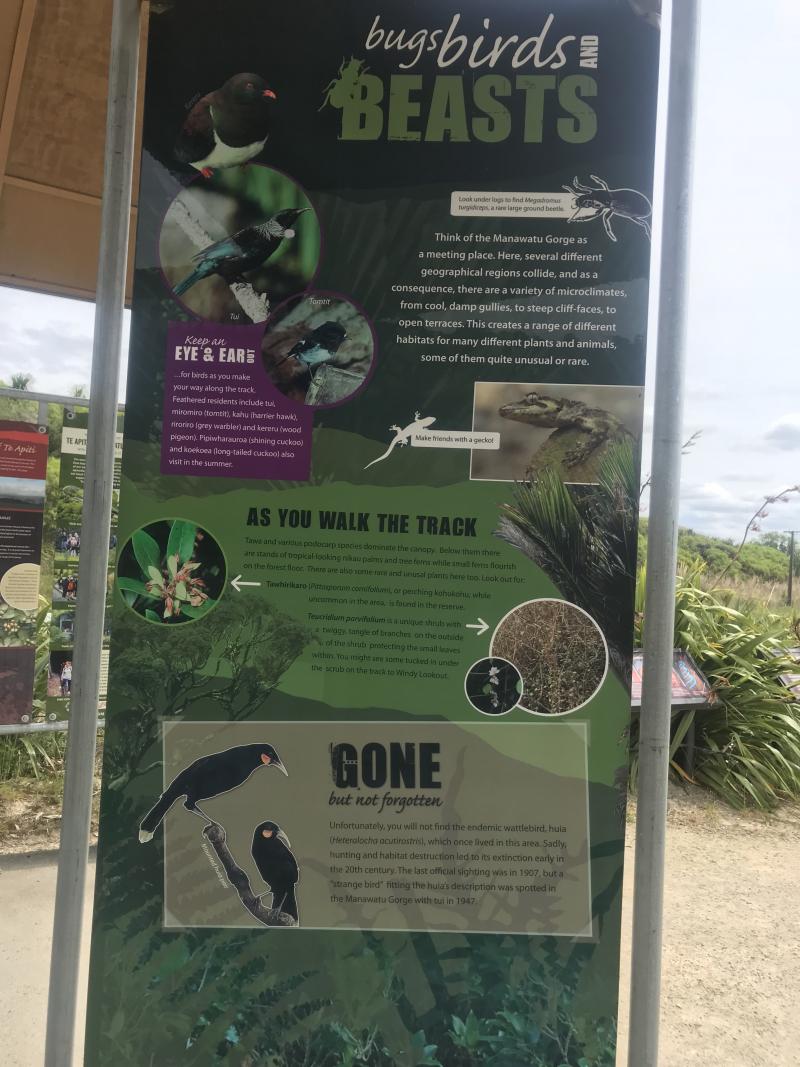

Photograph of an interpretive panel at the entrance to Manawatu Gorge Scenic Reserve, Te Apiti, Manawatu Gorge. While enjoying birds with eye and ear is encouraged in this signage, the 1907 and 1947 encounters reference Huia sightings, the prioritization of which is illustrated in William J. Phillipps’s The Book of the Huia (1963). Huia, for instance, chronicles a capture-to-save expedition during which “no birds were seen, though … the huia call was heard in foggy weather—scarcely a satisfactory or conclusive state of affairs,” the report concluded. Vocalizations also could be of descriptive interest (e.g., “a trill similar to that of the shining cuckoo but deeper in tone”). Huia sounds, however, did not meet “the need to prove that the bird still existed.” For example, in a referenced local 1947 spotting “of a ‘strange bird’ fitting the huia’s description,” the word “strange,” like “ghost,” estranges any still-fleshed birds from sensory expectations not sanctioned by the official 1907 narrative.

Photograph of an interpretive panel at the entrance to Manawatu Gorge Scenic Reserve, Te Apiti, Manawatu Gorge. While enjoying birds with eye and ear is encouraged in this signage, the 1907 and 1947 encounters reference Huia sightings, the prioritization of which is illustrated in William J. Phillipps’s The Book of the Huia (1963). Huia, for instance, chronicles a capture-to-save expedition during which “no birds were seen, though … the huia call was heard in foggy weather—scarcely a satisfactory or conclusive state of affairs,” the report concluded. Vocalizations also could be of descriptive interest (e.g., “a trill similar to that of the shining cuckoo but deeper in tone”). Huia sounds, however, did not meet “the need to prove that the bird still existed.” For example, in a referenced local 1947 spotting “of a ‘strange bird’ fitting the huia’s description,” the word “strange,” like “ghost,” estranges any still-fleshed birds from sensory expectations not sanctioned by the official 1907 narrative.

© 2017 Julianne L. Warren. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Similar searches, sponsored by Pākehā (a New Zealander of European descent) institutions, took place in the early twentieth century for a close relation of Kōkako—for vanishing Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris). The Eurocentric vanishing narrative also extends to peoples racialized and oppressed as non-white. In the nineteenth century, Pākehā ornithologist Walter Buller projected that the extinction of both the declining Huia and the “Māori race” would occur between 1884 and 1909. In 1922, Te Rangi Hiroa (Peter Henry Buck, Ngāti Mutunga, Irish-English), however, underscored a pēpeha (ancestral saying): “We will never be lost, for we spring from the Sacred Seed, which was sown from Rangiātea.” Contrary to an official narrative, many convincing reports indicated Huia were still living then.

This Anglo-colonialist Huia story could not be innocent of genocidal taint. In 1923, England-born J. G. Myers, a New Zealand Department of Agriculture scientist, looked back and published a final Huia date: 28 December 1907. This marked “the last specimens . . . actually seen” by a trustworthy witness—fellow ornithological society member, Scotland-born W. W. Smith. Also on 26 September 1907, New Zealanders had declared a semi-independent dominion within the British Empire, no longer their colony. The dominion remained colonizers, however. Implicitly, 1907 links this symbolic rise of localized power with the demise of Huia, known to be Māori taonga (treasures) linked with Māori mana (prestige). Repeating the original Myers-Smith Huia claim republished in a 1928 Evening Post article and thereafter cited in a succession of natural histories, the extinction narrative continues to resonate with a system disrupting Indigenous sovereignty, ecology, and ontology.

Photograph overlooking the area around Mount Aorangi and the Mangatera Stream where Henare Hamana accompanied 1908/09 government-sponsored Huia-search expeditions. With special thanks to Toby Salmon and Dave Salmon. At least two recent waiata integrate a “recreated call of the huia” featuring Hamana: “Tohu maumahara mō ērā kua hinga Memorial to the fallen” in Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, a lament composed by Morvin Simon (Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) and sung by him and Kura Simon; and, “Waiata Manu Huia” created and performed by Mike Kawana, Rangitāne o Wairarapa kaumatua, and others, as featured at Pūkaha National Wildlife Center/Mt. Bruce, Wairarapa. In his 1954 interview with Pākehā ethnologist William J. Phillipps, Hamana also indicated how colonialist disruptions of forests, Huia, and Māori culture, including funereal rites, intersect and relate. For instance, the last time he had witnessed the rite of “slashing of a body at a tangi [funeral],” Hamana said, was when he was seven, in 1887. Related to Māori resistance and recovery, however, he added: “A general belief still stands that the [wairua] spirit [leaving a body] goes north to Cape Reinga [traveling beyond]” the world of the living.

Photograph overlooking the area around Mount Aorangi and the Mangatera Stream where Henare Hamana accompanied 1908/09 government-sponsored Huia-search expeditions. With special thanks to Toby Salmon and Dave Salmon. At least two recent waiata integrate a “recreated call of the huia” featuring Hamana: “Tohu maumahara mō ērā kua hinga Memorial to the fallen” in Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, a lament composed by Morvin Simon (Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) and sung by him and Kura Simon; and, “Waiata Manu Huia” created and performed by Mike Kawana, Rangitāne o Wairarapa kaumatua, and others, as featured at Pūkaha National Wildlife Center/Mt. Bruce, Wairarapa. In his 1954 interview with Pākehā ethnologist William J. Phillipps, Hamana also indicated how colonialist disruptions of forests, Huia, and Māori culture, including funereal rites, intersect and relate. For instance, the last time he had witnessed the rite of “slashing of a body at a tangi [funeral],” Hamana said, was when he was seven, in 1887. Related to Māori resistance and recovery, however, he added: “A general belief still stands that the [wairua] spirit [leaving a body] goes north to Cape Reinga [traveling beyond]” the world of the living.

© 2017 Julianne L. Warren. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The Book of the Huia (1963), by Pākehā ethnologist William J. Phillipps, may be read as a partial repudiation of the 1907 Huia-extinction story. Huia acknowledges many well-supported “sightings” crediting “non-scientific observers” between 1890 and 1961. Phillipps cites a few Māori observations, although these remain incorporated into a Pākehā’s narrative that fails to honor Māori-Huia whanaungatanga (kinship rights and obligations). And, in Huia’s “sum of evidence,” hearings remained less often expressed. These were largely incidental to sightings during Huia capture or killing, whether for Māori customary uses, for selling skins and feathers (not voices!) in British-based markets, or, for the unsatisfied hope of delivering living birds to proposed sanctuaries. Furthermore, a 2017 article by Pākehā scientist-historian Ross Galbreath details the likelihood that Myers misdated a 1905 Huia sighting by Smith. And, in any case, that Myer’s 1907 claim cannot be cross-validated.

Meanwhile, between 1890 and 1910, note historians Carl Bradley and Rhys Ball, Māori “dual traditions of reform and protest . . . crystallised” against colonialism’s forced disconnections from lands, language, culture, and identity. Māori development expert Margaret Forster (Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu) stresses how the plural voice of Māori in various politics of resistance and cultural and ecological recovery “has never been silent.” Beyond the 1907 signposts, many voices, never silent, also call for listening. In 1909, Māori knowledge-holder Henare Hamana (Ngāti Awa, English) accompanied a Huia-search expedition organized by Dominion Museum-affiliated scientists. On this trip, imitating Huia calls, Hamana attracted at least one male bird. Hamana’s breath, whistling Huia-like phrases, continues to echo from a 1948 recording—a male and female in conversation.

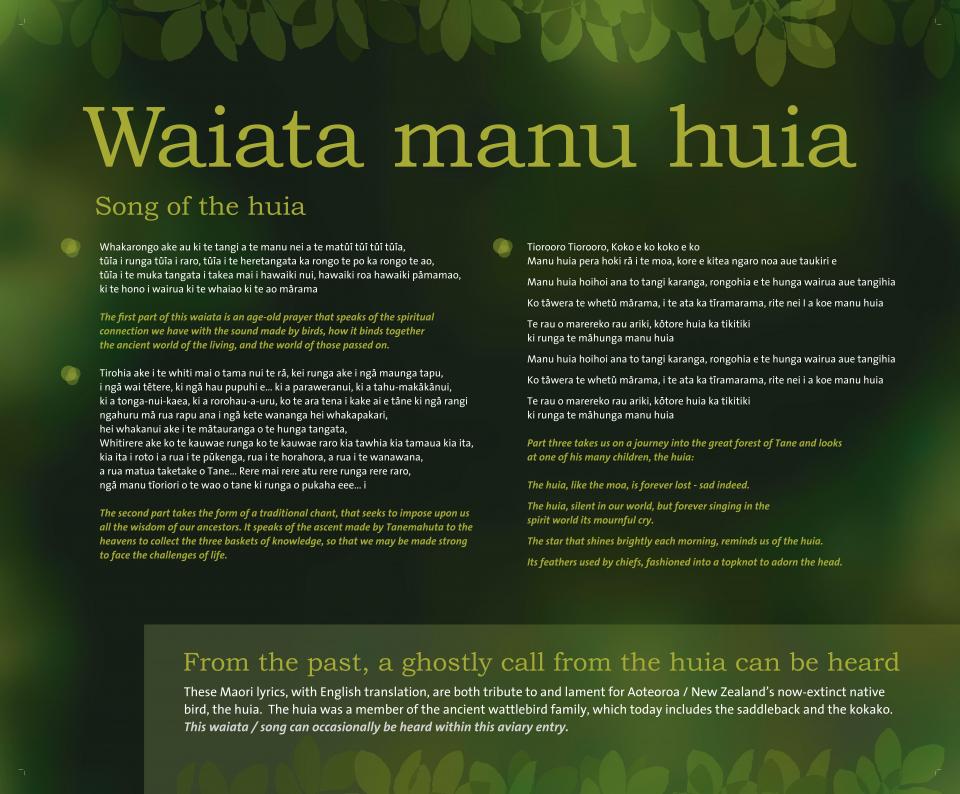

Photograph of interpretive panel at Pūkaha National Wildlife Center/Mt. Bruce, Wairarapa. Near the end of “Waiata Manu Huia” te karanga (ceremonial call), a ceremonial tribute bids farewell to Huia who are silent in the living world while “forever singing in the spirit world.” This sounds like an important part of grieving, which also allows ancestral relations to continue. This sounds incommensurable with an Anglo-abstraction of “extinction” and moves to grasp the vast loss by identifying and celebrating the lasts of a kind, “endlings,” along with the risk of taking an individual’s (soon-to-be) vacated body as merely an object and/or metaphor for an unrelatable mass of dead bodies. Moreover, how can anyone really grieve a life or lives that one has not first known?

Photograph of interpretive panel at Pūkaha National Wildlife Center/Mt. Bruce, Wairarapa. Near the end of “Waiata Manu Huia” te karanga (ceremonial call), a ceremonial tribute bids farewell to Huia who are silent in the living world while “forever singing in the spirit world.” This sounds like an important part of grieving, which also allows ancestral relations to continue. This sounds incommensurable with an Anglo-abstraction of “extinction” and moves to grasp the vast loss by identifying and celebrating the lasts of a kind, “endlings,” along with the risk of taking an individual’s (soon-to-be) vacated body as merely an object and/or metaphor for an unrelatable mass of dead bodies. Moreover, how can anyone really grieve a life or lives that one has not first known?

© Pūkaha National Wildlife Center and Earthstory. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Two recently composed waiata (songs) integrate this Hamana-Huia audio. In “Tohu maumahara mō ērā kua hinga Memorial to the Fallen” in Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, a waiata lamenting “the loss of the huia” animates dimly lit cases of skins, bones, and feathers beside lists of other now-invisible kin. In Pūkaha/Mount Bruce, “Waiata Manu Huia,” cultural audio by tāngata whenua (Indigenous hosts) Rangitāne, flows into this Huia-absented remnant of Te Tapere-nui-o-Wātonga (a.k.a. Seventy Mile Bush), the last substantial remainder of this vast forest of high importance to Rangitāne as well as the birds. During the nineteenth century, the New Zealand government had pressured Rangitāne to acquire the land.

“Waiata Manu Huia,” created and performed by Rangitāne~kaumatua Mike Kawana and others, audio recording, track 3 on “Pūkaha—Sounds of the Forest,” 2015, https://rangitaneeducation.com/pukaha-sounds-of-the-forest/.

In 2016, in Te Tiriti o Waitangi Treaty redress, New Zealand apologetically returned the remnant to Rangitāne. Rangitāne gifted the Pūkaha land for the “people of Aotearoa”—encouraging engagements with them/their land in just relations, mending whakapapa (genealogy), te reo Māori (language), and kaitiakitanga (sustainability ethics). “Waiata Manu Huia” speaks of Huia, relatives, like Moa, sadly silent in this world. Yet, “forever singing in the spirit world.” Sound made by birds binds both worlds in Māori genealogy and multisensory cosmology. “Ko tātou ngā kanohi ora” (“We are the living eyes”), also say Rangitāne kaitiaki land-keepers. “Waiata Manu Huia” concludes with a traditional calling in to relation, doing and being our best together: “Whano, whano! Haramai te toki! Haumi ē! Hui ē! Tāiki ē!”

How to cite

Warren, Julianne, and Michael Roche. “Sight and Sound: Beyond the 1907 Huia Extinction Story.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2022), no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9560.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2023 Julianne L. Warren and Michael Roche

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Cain, Trudie, Ella Kahu, and Richard Shaw, eds. Tūranga Wae Wae: Identity and Belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland, NZ: Massey University Press, 2018.

- Erai, Michelle. Girl of New Zealand: Colonial Optics in Aotearoa. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2020.

- Forster, Margaret. “Recovering Our Ancestral Landscapes: A Wetland's Story.” In Māori and the Environment: Kaitiaki, edited by Rachael Selby, Pataka J. G. Moore, and Malcolm Mulholland, 199–218. Wellington, NZ: Huia Publishing, 2010.

- Galbreath, Ross. “The 1907 ‘Last Generally Accepted Record’ of Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) Is Unreliable.” Notornis 64, no. 4 (2017): 239–42.

- Hiroa, Te Rangi (Peter Henry Buck). “The Passing of the Māori.” Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 55 (1924): 362–75.

- Ibbotson, Rosie. “De-extinction and Representation: Perspectives from Art History, Museology, and the Anthropocene.” International Review of Environmental History 3, no. 1 (June 2017): 21–42. doi:10.22459/IREH.03.01.2017.05.

- Phillipps, William J. The Book of the Huia. Christchurch, NZ: Whitcombe and Tombs, 1963.