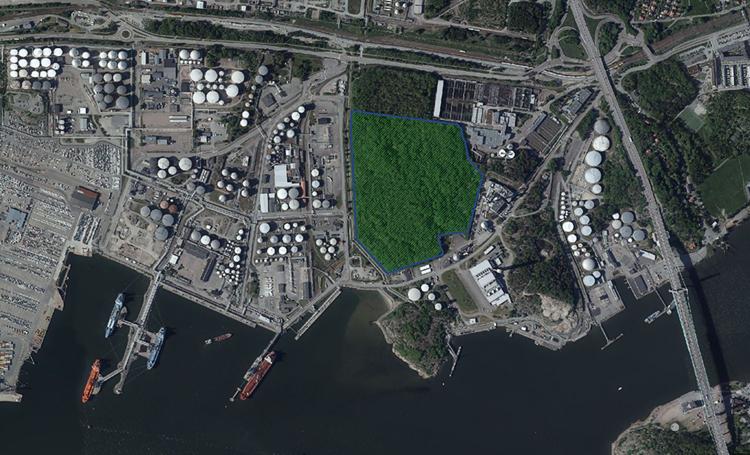

In 1923 botanist Carl Skottsberg wrote of Rya Forest, located in the outskirts of Gothenburg on the west coast of Sweden: “In this mostly rocky and bare area it stands out as a friendly oasis, a last remnant of a formerly grand forested landscape” (Skottsberg 1923, 315). Back then, this was a rural region. Today Rya Forest is a small patch of green—a nature reserve appreciated for its biological diversity, abundant birdlife and old oak trees—right in the middle of industrial land, oil cisterns, roads, and railway tracks. The words of Skottsberg carried an appeal for its protection at a time of rapid modernization.

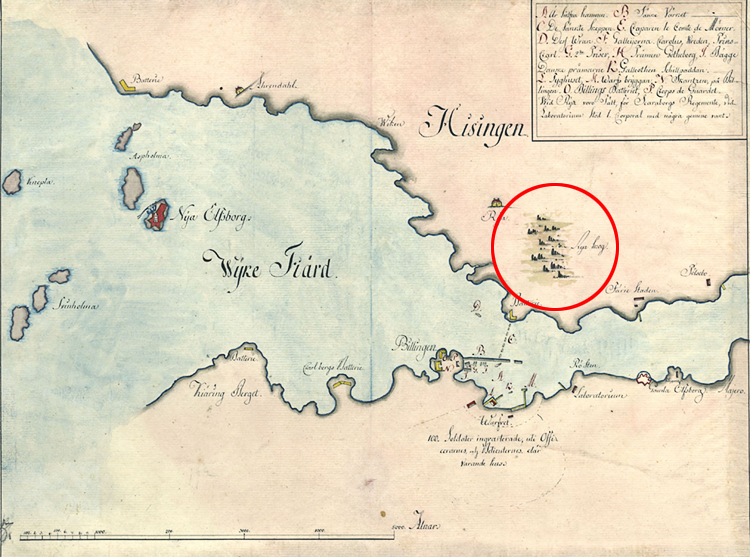

References to Rya Forest date back several centuries. On a military map from 1719, the forest is the only specified natural feature, and traces of a bulwark from that time can still be seen in the nature reserve. However, it was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that the area became the subject of environmental concern.

Military map from 1719 of the Gothenburg harbor entrance. Rya Forest is marked with a red circle.

Military map from 1719 of the Gothenburg harbor entrance. Rya Forest is marked with a red circle.

Unknown cartographer, 1719.

Courtesy of Krigsarkivet, Sveriges Krig Stora Nordiska kriget 0425:14:100 1719.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 30 August 2019, modified by Björn Billing. Click here to view the source of the original image.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This took place in the wake of Sweden’s first Environmental Act and the foundation of the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (SSNC), both established in 1909. The calls for making Rya Forest a protected area rested on a number of notions. Environmentalists emphasized biological importance as well as aesthetic qualities. As Gothenburg expanded its urban territory, fear grew that this green haven would be threatened by the intrusive and destructive city. New roads facilitated access to the beaches near Rya Forest, and recreational bathers left litter in the area. It was also argued that some delicate habitats with rare plants needed protection from grazing animals and thoughtless land management. Even nature lovers were a threat, namely botanists who removed specimens for their own collections.

The first formal petition was written in 1913. Several were to follow during the next fifteen years, often in direct response to commercial plans. One such event occurred in 1916 when an advertisement in a daily newspaper announced 28 selected oaks for sale to the highest bidder. Since the land was Crown property the SSNC appealed to the King-in-Council and the trees were left intact. The protection of Rya Forest became increasingly urgent as the years went by. Arguing from a systemic perspective influenced by contemporary theories of plant ecology, environmentalists stressed that legal protection should not be limited to rare species but ought to encompass the whole area. In addition, the visual impression of the diverse landscape was highlighted as an aesthetic quality.

Equally essential for the picturesque beauty was the primordial character: this was “a wild forest, where nature itself has been the gardener” (Liljedahl 1921, 73). Consequently, Rya Forest should “by all available means be protected from any encroachment at odds with natural evolution” (Ibid.). As pure nature, this unspoiled place could remind the visitor of permanence and deep history in contrast with the rapid tempo of urban development.

By royal decree, Rya Forest was protected by the law on 5 February 1928 as a natural landmark (later nature reserve). From this date onwards it was illegal to cut down trees and bushes, to break twigs or remove them from the ground, to pick flowers, to hunt and kill animals or snatch bird eggs, to erect buildings, to make fire, and to let cattle graze. The effect was paradoxical as vegetation went literally wild. Paths and glades were overgrown, the forest became darker, biodiversity decreased. Environmentalists expressed concerns that Rya Forest was becoming “impenetrable, junglelike and severely brushy”, and as a consequence less attractive and accessible (Feodor Aminoff quoted in Malmström 1962, 22). Obvious in hindsight, Rya Forest had not been wild nature at all but a landscape shaped by foraging, scythe mowing, and other forms of husbandry. In March 1940 a restoration plan was formulated to counteract this unwanted rewilding. Through proper environmental management, taking visitors’ experience into consideration, the bright and inviting character of Rya Forest was to be recreated.

Legal protection did not mean that Rya Forest was forever safeguarded. The area, strategically located at the port entry, was repeatedly targeted by industry and commerce, which resulted in a number of modifications from the mid 1940s onwards. Pipelines for oil and water cut through the forest and infrastructure chipped away its edges. Step by step almost ten percent of the territory was lost. The most significant change took place in 1958 with the construction of a sewage treatment plant, Ryaverket, today the largest of its kind in Sweden. It was preceded by a heated debate among stakeholders and in the newspapers. The case escalated to symbolic proportions, and one journalist even headlined it as “the major preservation issue of a generation”. In the end Ryaverket claimed a fifth of the nature reserve, leaving sixteen hectares.

Today the lush Rya Forest is almost hidden in the midst of a grey industrial cityscape. It is small and unobtrusive, like so many of Sweden’s 5,000 nature reserves, but in several respects its modern history mirrors Swedish environmentalism at large and the challenges organizations such as the SSNC have been facing to this day.

How to cite

Billing, Björn. “Rya Forest Nature Reserve: A Case of Preservation, Conflicts, and Unwanted Rewilding.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. 6. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8972.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Björn Billing

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Anon. “Reningsverket i Rya skog är generationens största naturvårdsfråga.” Ny tid, 14 June 1957.

- Gardell, C. J. “Rya skog vid Göteborg: Ett naturminne, värdt att bevaras.” Sveriges Natur: Svenska Naturskyddsföreningens årsskrift (1915): 31–38.

- Liljedahl, Axel. “Rya skog vid Göteborg: En viktig naturskyddsfråga för västkusten.” Sveriges Natur: Svenska Naturskyddsföreningens årsskrift (1921): 72–79.

- Malmström, Carl. Rya skog i Göteborg. Uddevalla: Skogssällskapet, 1962.

- Skottsberg, Carl. “Göteborgstraktens växtvärld.” In Göteborgstraktens natur, edited by Otto Nordenskjöld, 289–332. Göteborg: Göteborgs jubileumspublikationer, 1923.

- Stenström, Jonas, and Martin Holmer. Rya skog: Forntidsskog i framtidsland. Göteborg: Naturcentrum, 1996.

- Wramner, Per, and Odd Nygård. Från naturskydd till bevarande av biologisk mångfald: Utvecklingens av naturvårdsarbetet i Sverige med särskild inriktning på områdesskyddet. No. 2. Södertörn: COMREC Studies in Environment and Development, 2010.