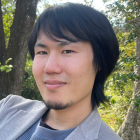

This short piece suggests that a poly-centered approach to the baroque should consider the relationship that eighteenth-century China had with Europe. Granting baroque paintings of nature and wildlife the cultural and political significances they embodied at the time could be a step toward the recognition of a global baroque. The Qing’s inordinate interest in cavalry maneuvers and hunting rituals was related to the dynasty’s celebration of its non-Chinese identity. The Qing court acquired European baroque knowledge and techniques primarily in order to project legitimacy and prestige across the different cultures of the Qing Empire. By promoting these techniques, models, and standards, the Catholic artists and scholars in residence at the Manchu court conveyed a message about the legitimacy and universality of a dynasty that ruled on both sides of the Great Wall, from the steppes of Kazakhstan to the jungle of Guangxi. The command of a common pictorial language facilitated the exchanges that linked King Louis XV of France to the Qianlong emperor and connected the two monarchs’ conceptions of glory and duty. The spectacle of European-looking horses grazing peacefully in the Mongolian prairie leads therefore to fundamental questions about the place of art and the environment in empire building.

The reception of foreign dignitaries and tribute bearers by the Emperor (Beijing): The representation of the Chinese baroque by a European baroque painter at the Qing court. Detail from Giuseppe Castiglione, Qazak Paying Tribute of Horses to Qianlong Emperor, 1757.

The reception of foreign dignitaries and tribute bearers by the Emperor (Beijing): The representation of the Chinese baroque by a European baroque painter at the Qing court. Detail from Giuseppe Castiglione, Qazak Paying Tribute of Horses to Qianlong Emperor, 1757.

Painting by Giuseppe Castiglione, 郎世寧 (1688–1766).

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

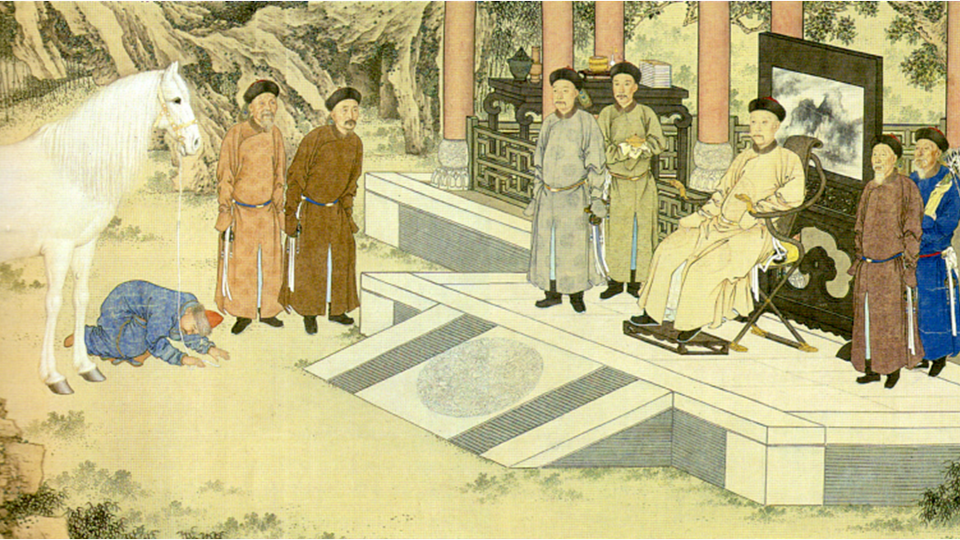

Until very recently, research on the baroque has restricted itself to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and to the parks, palaces, paintings, literature, and music of Europe. The baroque we are typically familiar with is born from Counter-Reformation iconography and from a rejection by Roman Catholicism of the clear and fixed ways of looking at the world that had been prevalent during the Italian Renaissance. Baroque was already flourishing in Catholic Europe when, in 1581, the first missionaries who were experts in the representation of nature landed in Macau. A century later, the Kangxi emperor appointed in Beijing Jesuit painters from Italy, France, Bohemia, and Portugal who merged European figure painting with Chinese landscape painting. Sarah E. Fraser has argued that the styles and techniques of European baroque facilitated the emergence of radically new visual modes at the imperial court. At the conference that she convened in Heidelberg in 2015, “Jesuit Legacies: Images and Visuality in Ming-Qing China,” scholars agreed that this transfer of knowledge unleashed a visual revolution. Yet current scholarship on the portrayal of the emperor’s daily life, high-ranking officials, and significant events, as well as Manchu values and claims, does not do justice to the images of nature that Castiglione, Attiret, Ripa, Sichelbarth, and Moggi made.

Hunting scene in the imperial hunting ground of Mulan (Mulan, Hebei): The representation of Chinese nature by a European baroque painter at the Qing court. Detail from Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor Hunting Hare, 1755.

Hunting scene in the imperial hunting ground of Mulan (Mulan, Hebei): The representation of Chinese nature by a European baroque painter at the Qing court. Detail from Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor Hunting Hare, 1755.

Painting by Giuseppe Castiglione, 郎世寧 (1688–1766).

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

To understand fully the visual revolution that occurred in Qing Beijing, we must revise the definition of baroque to go beyond particular, invariant spaces and times, and European cultural areas. Rather, baroque should be understood as a multicultural, intergeographical, and transhistorical entity that represents shared values attached to an emotional conceptualization of the dialectics of nature and culture. The baroques of the princely bishops’ residence of Eichstätt and of the Church of Saint Dominic in Macau are only avatars of the same universal baroque—newly redefined as exuberant, emotional, and dynamic. Like d’Ors at the entretiens of Pontigny (1931), we hypothesize that baroque is a notion that transcends cultural, spatial, and historical boundaries. We endorse the idea that baroque aesthetics, which symbolize “capriciousness and return to chaos” (Wölfflin), do not need to be safely anchored in only one continent, only one religion, and only two centuries. Transculturation as defined in Foucault’s “heterotopia” is a leading concept in our definition of a baroque that innovates in its depiction, rendition, and appropriation of nature. We follow the precedents set by Zhuang (2017) who has studied transcultural performances and the entanglement of landscape exchanges between China and England, and by Parkinson Zamora and Kaup (2010) who have studied the baroque architecture of Latin America.

The imperial pastures of Mulan (Ulan Butong, Inner Mongolia): The representation of nature by a European baroque painter at the Qing court. Detail from Giuseppe Castiglione, One Hundred Horses, 1728.

The imperial pastures of Mulan (Ulan Butong, Inner Mongolia): The representation of nature by a European baroque painter at the Qing court. Detail from Giuseppe Castiglione, One Hundred Horses, 1728.

Painting by Giuseppe Castiglione, 郎世寧 (1688–1766).

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The confusion, coherence, completeness, promise, and abundance that we see in the European baroque are also visible in the Chinese baroque. The Manchus processed deliberately nature-related themes and concepts from Europe, and the encyclopedias that they commissioned included European paintings of exotic birds and wild animals. The baroque representation of nature is also present in the history of Qing China’s engagement with European culture. This presence can be felt in court portraits of the Manchu nobility, landscape paintings or engravings of garden vistas, hunting scenes in Mulan, and the imperial residences of Beijing and Chengde. Our case studies come from the designed landscapes of the dynasty’s winter and summer capitals, the Mulan hunting grounds, and from Yangshi Lei’s maps and plans like the Xiyang Lou in the Yuanming Yuan residence or Qianlong’s retreat studio in the Forbidden City. Thanks to the market it has created and the products it has fashioned, the Chinese baroque nourished a rich dialogue between civilizations and across centuries. As environmental historians, our task is now to enrich with historical evidence from Asia both our analysis of nature in the global baroque and our experience of engagement with early modern cultures. We will thus be able to explain why, four centuries ago, two visual cultures decided to represent nature together.

How to cite

Forêt, Philippe. “The Qianlong Emperor Hunting Hare: From the Qing Esthetics of Nature to an End of European Exceptionalism.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2018), no. 25. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8479.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 Philippe Forêt

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- D’Ors, Eugenio. Du Baroque. Paris: Folio, 2000.

- Forêt, Philippe. Mapping Chengde. The Qing Landscape Enterprise. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000.

- Maffesoli, Michel. Au creux des apparences. Pour une éthique de l’esthétique. Paris: Plon, 1993.

- More, Anna Herron. Baroque Sovereignty. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

- Parkinson Zamora, Lois. and Monika Kaup, eds. Baroque New Worlds. Representation, Transculturation, Counterconquest. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

- Wölfflin, Heinrich. Renaissance and Baroque. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967. (Translation of Renaissance und Barock, 1888.)

- Zhuang, Yue and Andrea Riemenschnitter. Entangled Landscapes: Early Modern China and Europe. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2017.