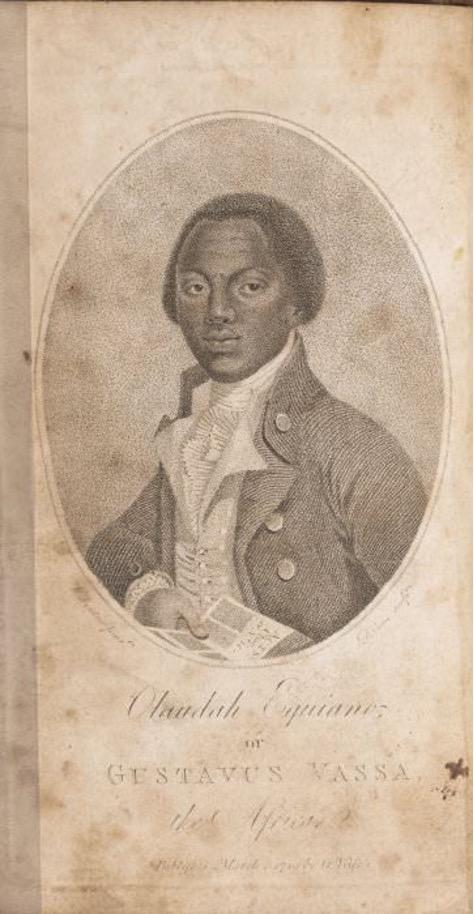

Born around 1745 in the Kingdom of Benin, Olaudah Equiano was kidnapped into slavery as a child. Keen “to improve” himself despite his unfreedom, Equiano received a smattering of intellectual and religious instruction. Equiano’s yearning for “a good education” grew in tandem with his drive for emancipation, which he earned in 1766. A couple of years later, Charles Irving, a specialist in water purification, hired Equiano. The British Navy recognized Irving’s potential value to its upcoming expedition that would, in the words of backer Daines Barrington, aim to find “a passage by or near the North Pole to the East Indies.” As a result, the doctor and Equiano gained spots on the HMS Racehorse in 1773. Notably, Equiano was not just a deckhand, as evidenced by his autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (hereafter Narrative). Equiano’s experience in bondage equipped him to evaluate the entanglement between poles of exploration and exploitation in history and today.

Portrait of Olaudah Equiano with a book in hand.

Portrait of Olaudah Equiano with a book in hand.

Unknown creator. Published in Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (London: printed and sold by the author, 1789).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

From the start, Equiano doubted this trip for spiritual and rational reasons, implying that their goal was one that “our Creator never intended we should” achieve. In a sense, Europeans’ appetite for scientific knowledge emerged from a yearning to drive markets through African labor: Both placed subjects in terrains of duress and pushed them toward death in the name of civilization. After all, a path to India would have reinvigorated inequitable global markets. For Equiano, avarice drove Englishmen to find this route, blinding them to the consequences for humans and the environment. Although the English could choose to suffer while seeking the North Pole and Open Polar Sea, slaves sought “refuge in death from those evils which render their lives intolerable,” namely masters who utilized muzzles, thumbscrews, and beatings.

Equiano voiced his equivocations by depicting his confrontations with death in the Arctic as a series of holy crises. On the first occasion, Equiano set his room on fire by knocking over a candle. He described the scene as if the flames were heavenly censures: “Immediately the whole was in a blaze. [He] saw nothing but present death before [him].” Equiano fashioned this debacle as a katabasis of sorts. In confusing the boundaries between the literal and the metaphysical, Equiano hinted that the mission engendered celestial retribution. On another day, he almost drowned, only to be “providentially” saved by shipmates. Similar to his earlier misfortune, Equiano straddled between life and death, salvation and damnation. By elevating these trials of severe heat and cold to almost Biblical allegories of punishment, Equiano signaled disapproval for the expedition.

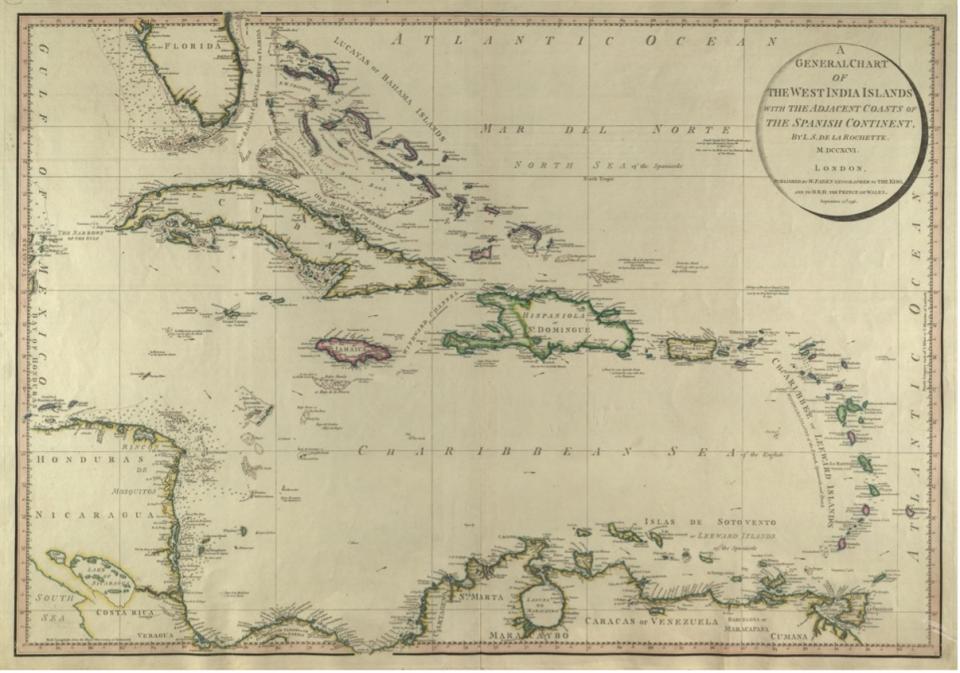

Map of the West Indies, an area of Equiano’s enslavement.

Map of the West Indies, an area of Equiano’s enslavement.

1769, L. Louis Delarochette. Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Rare Map Collection. Click here to view the source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

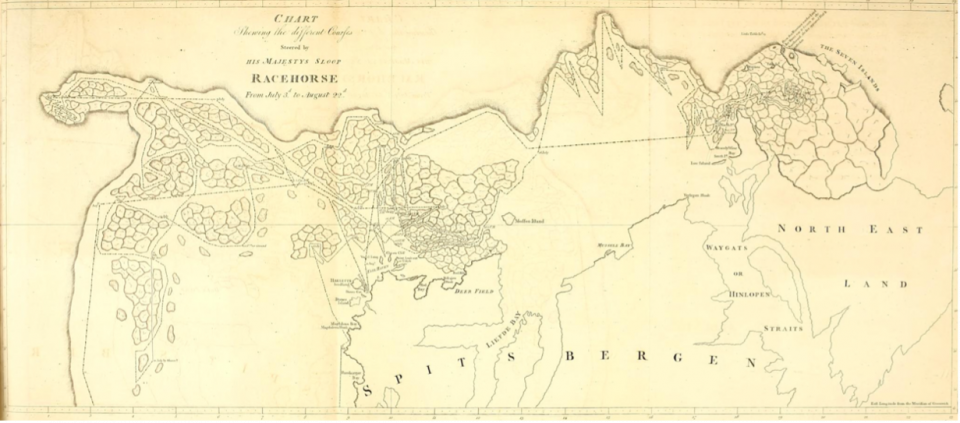

Equiano further disclosed his concerns through a rhetoric of unease. He expressed this discomfort with his responsibilities through words such as “dejected,” “deplorable,” and “miserable.” With “the fears of death hourly upon me,” Equiano proclaimed even routine jobs profane. While distilling salt water, he worried that he “really began to give up [him]self for lost.” Equiano “shuddered at the thoughts of meeting the grim king of terrors in the natural state” he was in, terrified that he would perish in the extreme landscape. After reaching their farthest point of 80°48’ north, the crew met ice when trying to advance. Gazing at the gelid horizon before them, members resigned to return to England. Notably, the tour’s inability to find a passage to Asia fulfilled the prophecy Equiano outlined: It “fully proved the impracticability of finding a passage that way to India.”

Shipmates laboring on the ice.

Shipmates laboring on the ice.

Published in Constantine John Phipps Mulgrave, A Voyage Towards the North Pole Undertaken by His Majesty’s Command 1773 (London: W. Bowyer and J. Nichols for J. Nourse, 1774).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Although relieved when he set foot on shore, Equiano still harbored conflicted sentiments about the nautical failure. Pondering his proximity to the brink of existence, the sailor wondered why his superiors put themselves at risk. Equiano joined the vessel primarily for work and pay, unlike the scientists and explorers on board. As it became clear to Equiano—who privileged the immortality of his soul—Englishmen put the crews at “imminent hazard” because they sought renown and riches. Death, then, would bring divergent fortunes to whites and nonwhites. As a consequence, the freedman implied that desires for mastery over space, peoples, and knowledge guided the voyage. He intuited that the Arctic elicited a worth resonant to explorers as the maritime networks among countries with plantations did to slaveowners. Indeed, Equiano insinuated how exploration and enslavement were exercises in expansionism and inhumanity.

The course of the HMS Racehorse, the ship on which Equiano traveled.

The course of the HMS Racehorse, the ship on which Equiano traveled.

Published in Constantine John Phipps Mulgrave, A Voyage Towards the North Pole Undertaken by His Majesty’s Command 1773 (London: W. Bowyer and J. Nichols for J. Nourse, 1774).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In this vein, Equiano disrupts accounts of Arctic history as a succession of white men. Although Equiano never mentioned encountering Inuits, he met Miskitos a few years later. His mixed reaction offers insights into how he might have responded to Indigenous communities up north. On one side, Equiano praised “native Indians” for their “singular . . . honesty.” Despite his admiration for this quality, Equiano also wrote with a register of distance due to his different religion. Equiano judged that “this heathenish form was very irksome” and unsuccessfully attempted to convert some of his hosts to Christianity. Even if conflicted, Equiano enjoyed having “different nations and complexions” beside him, gesturing his appreciation for being accompanied by other nonwhite figures.

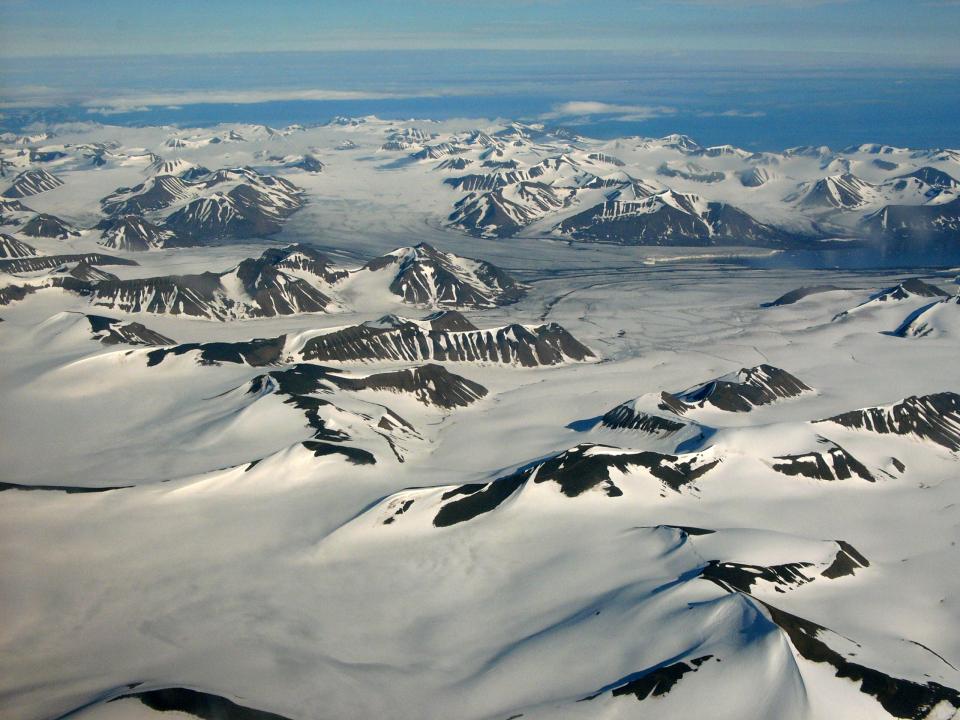

Modern-day image of the region Equiano visited.

Modern-day image of the region Equiano visited.

26 October 2007, Hannes Grobe. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

The Narrative holds relevance in our age of climate change and societal disparity. The ice that once blocked HMS Racehorse will resist commercial vessels less and less in the coming decades. Viewed as a route of increasingly tantalizing profits, the Northwest Passage’s loss of seasonal sea-ice cover will fuel further use. But paradoxically, the more the pathway opens, the fewer possibilities exist for actions to protect our futures. Admittedly, conditions have shifted since Equiano visited the Arctic; nonetheless, similar problems of racial equity and environmental justice he confronted remain entrenched. Accelerated by global warming, modern extractive economies damage Inuit communities in racialized ways: These poles of exploitation and exploration persist.

PRIMARY SOURCES

- Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. London: printed and sold by the author, 1789.

How to cite

Jacob, Henry. “Poles of Exploration and Exploitation: Olaudah Equiano in the Arctic.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2022), no. 17. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9549.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Henry Jacob

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Bloom, Lisa. Gender on Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

- Bravo, Michael. North Pole: Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- Craciun, Adriana. Writing Arctic Disaster: Authorship and Exploration. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Heuer, Christopher. Into the White: The Renaissance Arctic and the End of the Image. New York: Zone Books, 2019.

- Kaaland, Nanna Katrine Lüders. Explorations in the Icy North: How Travel Narratives Shaped Arctic Science in the Nineteenth Century. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021.

- Nuligak. I, Nuligak. Edited and translated from the Eskimo by Maurice Metayer. Toronto: Peter Martin Associates, 1966.

- Savours, Ann. “‘A Very Interesting Point in Geography’: The 1773 Phipps Expedition Towards the North Pole.” Arctic 37, no. 4 (1984): 402–28.