Large-scale industrial pollution, the growing threat of nuclear radiation, documented mass destruction of entire ecosystems around the globe: the 1960s witnessed the advent of widespread international concern about a global environmental crisis. As this heightened global awareness triggered a modern environmental movement, it was the initiative of a small country in Scandinavia that laid the foundation for international cooperation on environmental matters.

A view of the New Parliament building in Stockholm where some of the conference meetings were being held

A view of the New Parliament building in Stockholm where some of the conference meetings were being held

All rights reserved © 1972 UN

Click here to view UN source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

On 13 December 1967, a proposal reached the United Nations General Assembly to organize a conference in order to “facilitate co-ordination and to focus the interest of member countries on the extremely complex problems related to the human environment.” It was the Swedish delegation, led by Sweden’s UN Representatives Sverker Ästrom and Borje Billner, who took the initiative to convene the first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) in its capital city of Stockholm in 1972. By the late 1960s, Sweden had established itself as a respected middle power, oftentimes challenging the Superpowers and their Cold War status quo. Instead, Swedish diplomats tried to use the UN system to shift the diplomatic focus away from a nuclear paradigm towards more concern for international development and environmental protection.

Two years after their initial proposal, on 15 December 1969, UN Resolution 2581(XXEV) affirmed that:

It should be the main purpose of the Conference to serve as a practical means to encourage, and to provide guidelines for, action by Governments and international organizations designed to protect and improve the human environment and to remedy and prevent its impairment, by means of international cooperation, bearing in mind the particular importance of enabling the developing countries to forestall the occurrence of such problems.

—Resolution 2581(XXEV), UN General Assembly, 15 December 1969

As soon as the ‘‘Swedish matter,’’ as the preparation for the conference became known among UN officials, was formerly accepted, the Swedish delegation led the preparatory process to bring attention to environmental problems to the highest level of international diplomacy.

A general view of the opening meeting of the UN Conference at the Folkets Hus in Stockholm

A general view of the opening meeting of the UN Conference at the Folkets Hus in Stockholm

All rights reserved © 1972 UN / Yutaka Nagata

Click here to view UN source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

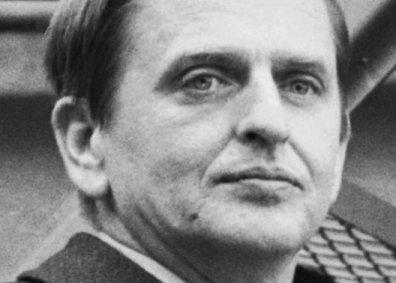

Sweden’s Prime Minister Olof Palme (early 1970s)

Sweden’s Prime Minister Olof Palme (early 1970s)

Photo by Oiving (early 1970s)

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

On 5 June 1972, the UN Conference on the Human Environment opened its first plenary session at the Folkets Hus in Stockholm. As host, Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme restated that his government attached the greatest importance to the success of the conference. His speech also openly criticized the industrialized world for its ecological and economic exploitation, causing the world’s greatest environmental problems at the expense of developing countries. While his critique was emblematic for the general tensions between developed and developing countries, which continued throughout the conference, the 114 governments represented in Stockholm reached an unprecedented level of agreement. Not least due to the diplomatic skills of the conference’s Secretary-General Maurice Strong, UNCHE not only established a remarkable Declaration of Principles, but also came up with the necessary institutional arrangements for international cooperation in environmental protection. The most important outcome being the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India, addressing the conference. Together with other leaders of the developing world, Gandhi singled out poverty as the main cause for environmental degradation and demanded greater responsibility and development aid from the industrialised countries.

Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India, addressing the conference. Together with other leaders of the developing world, Gandhi singled out poverty as the main cause for environmental degradation and demanded greater responsibility and development aid from the industrialised countries.

All rights reserved © 1972 UN / Yutaka Nagata

Click here to view UN source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

What further set the Stockholm summit apart from former UN conferences was the amount of popular interest and civil participation. Sweden’s quest for an open and inviting conference setting, which broke with traditionally rigid UN formats, opened the way for civil actors to raise their own concerns about the environment. Accordingly, the number of activists and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that attended the events in and around the conference was unprecedented. Through the Environment Forum, as well as through demonstrations and petitions, activists and NGOs opened up the dialogue about the various environmental and development issues and tried to influence the conference delegates. This would set the precedent for most big UN conferences and culminated in the thousands of NGO activists that would gather at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro .

An environment forum took place at the National School of Art in Stockholm on 7 June.

An environment forum took place at the National School of Art in Stockholm on 7 June.

An environment forum took place at the National School of Art in Stockholm on 7 June. At the table, from left: co-authors of “Blue Print for Survival”, Edward Goldsmith and Dr. Harman Daly; Allen Nadler, Scientist Instructor for Public Information, New York; Kariba Munio (Kenya), Instructor for Black Study, University of Colorado; Allan N. Williams (Guyana), Instructor for Economics, University of Miami; Clemente Forero (Colombia), Department of Economics, Stanford University; and Miriam Crawford, Representative of Navajo Indians, Black Mesa, Arizona.

All rights reserved © 1972 UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata

Click here to view UN source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

An environmentalist group demonstrates outside the New Parliament building during one of the conference sessions.

An environmentalist group demonstrates outside the New Parliament building during one of the conference sessions.

All rights reserved © 1972 UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata

Click here to view UN source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The UN Conference on the Human Environment marked a watershed in the evolution of humanity’s relationship with the earth and global concern about the environment. While most of the conference’s accomplishments were mainly rhetorical, its ultimate success was that environmental policy became a universal concern within international diplomacy, and the conference’s motto of “Only one Earth” became iconic for the modern environmental movement.

How to cite

Grieger, Andreas. “Only One Earth: Stockholm and the Beginning of Modern Environmental Diplomacy.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2012), no. 10. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/3867.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2012 Andreas Grieger

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Caldwell, Lynton K. International Environmental Policy: From the Twentieth to the Twenty-First Century. 3rd ed. Revised and updated with the assistance of Paul Stanley Weiland. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996.

- Ivanova, Maria. "Designing the United Nations Environment Programme: A Story of Compromise and Confrontation." International Environmental Agreements 7 (2007): 337–61.

- Strong, Maurice. "One year after Stockholm: An ecological approach to management." Foreign Affairs 51 (1973): 690-707.

- Ward, Barbara, and René Dubos. Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet. New York: Norton, 1972.