Logistics, both materially and metaphorically, is tied to histories of urbanization. As both a managerial rationality and a material practice for reorganizing global space in service of expanding the total circuit of flows, it fundamentally depends on cities and their infrastructures to keep the constant movement of flows going. The built systems that coordinate the circulation of goods, ideas, and capital into integrated networks—from roads and railways to loading docks, bonded warehouses, and global communications—shape urban environments by creating operational landscapes of connectivity and transmission, designed according to a paradigm of efficiency and control.

In all these regards, logistics has been central to Singapore’s urban development. The city-state has always been highly prized for its location at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, offering a central hub for East-West trade routes. Its great importance as a port settlement can be traced to the fourteenth century, when the island was known as Temasek.

Shaped by maritime commerce, even colonial Singapore was held together neither by a single language nor by political integration—although it formed part of the British Empire. Rather, it was defined by mobility and circulation, that is the constant flow of goods, people, and commodities: a logistics city integrated by trade and the forces of capital in search of profits on the forest frontiers of Southeast Asia that, if we follow Deborah Cowen, was “dedicated to servicing the system of stuff in motion.” Or: a city designed to serve as logistical space.

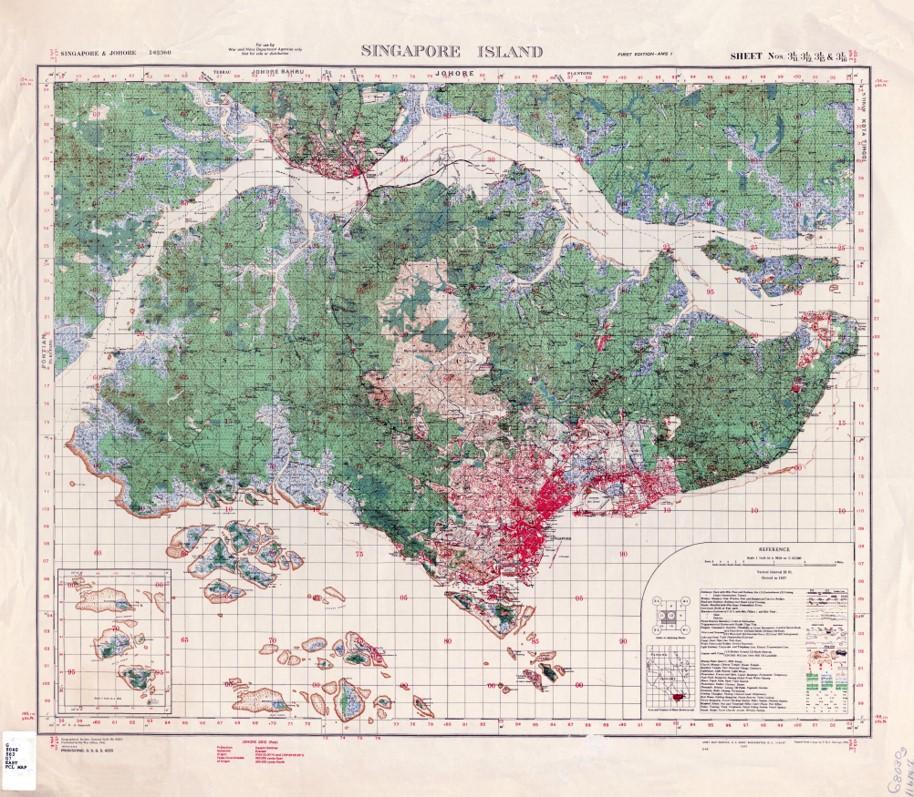

Map of the British Colonial War Office depicting Singapore island’s urban landscape and forests, 1941.

Map of the British Colonial War Office depicting Singapore island’s urban landscape and forests, 1941.

Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

With growing scholarly attention on the effectiveness of logistics in regulating political, economic, and social lifeworlds, this brief reflection seeks to add a more ecologically informed perspective on Singapore’s well-known urban history. Therefore, my question is not only whether logistics has shaped the city as such. But also, how it affected existing ecologies on site.

This much is certain: urban layouts and infrastructures destined to distribute “stuff” between markets must inevitably collide with existing environments. And in Singapore, the key arena in this context has always been territory. Prior to colonization, Singapore Island’s shoreline consisted of mostly swamps and marshes, which provided fertile grounds for the indigenous Malays and Orang Laut. British rule, on the other hand, gradually turned these livelihoods into infrastructure.

While, according to Brian Larkin, infrastructures are “matter that enable the movement of other matter,” logistics on the other hand is about how this movement is coordinated and, by implication, optimized. One of the most striking logistical transformations was in the physical features of the island—its vegetation, topography, soils, and shoreline. As more and more land would be reclaimed over the years, new logistical ecologies unfolded in this territorial stretching. Similar to port facilities or warehouses themselves, these environments were engineered for the smoothest possible flow of materials. As a result, logistics and urbanization intertwined in such a way that “natural” and logistical ecologies of circulation, transport, and cargo could no longer be separated.

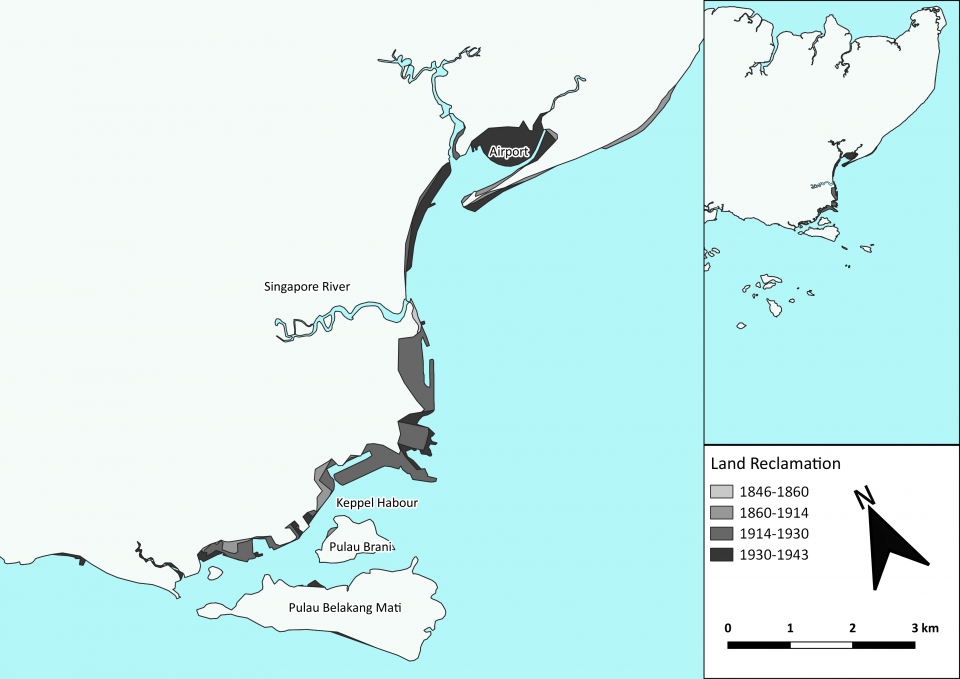

Map of reclaimed land during Singapore’s colonial period.

Map of reclaimed land during Singapore’s colonial period.

© Felix Mauch and David Stäblein, n.d.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This chapter of the Singapore Story has many origins. In 1822, Stamford Raffles initiated the first land reclamation project along the south bank of the Singapore River in order to move the commercial center there. Predominantly Tamil workers, forced to the city from the Malabar region and the Coromandel Coast, leveled the swampy estuary and created the fundament for shipping terminals. Some decades later, hundreds of indentured Indian convicts were to dredge the seabed to facilitate what would be home to New Harbour, a deep-water entrepôt port outside the initial city’s limits.

The location, known to Chinese travelers as Long Ya Men (龍牙門) since the fourteenth century, had been rediscovered by William Farquhar in 1820. But it was Henry Keppel who gave the decisive push to develop the area. In a diary entry dated 30 May 1848, the British admiral expressed his astonishment to find such deep waters close to the shore: “Now that steam is likely to come into use, this readymade harbour as a depot for coal would be invaluable.” He had the position surveyed and sent a detailed hydrographic report to both the Board of Admiralty and the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company.

Digitized image that shows the “natural” state of New Harbour.

Digitized image that shows the “natural” state of New Harbour.

Courtesy of British Library.

Unknown illustrator, possibly John Cameron.

Accessed via Flickr on 19 October 2021. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Once the P&O took possession, ocean shipping quickly favored the modern wharves, while coastal traffic continued to anchor off the river mouth. Transshipment cargo would then have to oscillate between the two locations. So once again the colonial Public Works Department employed its reclamation techniques to tame the island’s geomorphology. Marshland and mangrove swamps were transformed into roads and railway tracks, thereby “sanitizing” the urban landscape from perceived threats such as tigers, mosquitos, and malaria, as Miles Powell and Sunil Amrith have argued elsewhere.

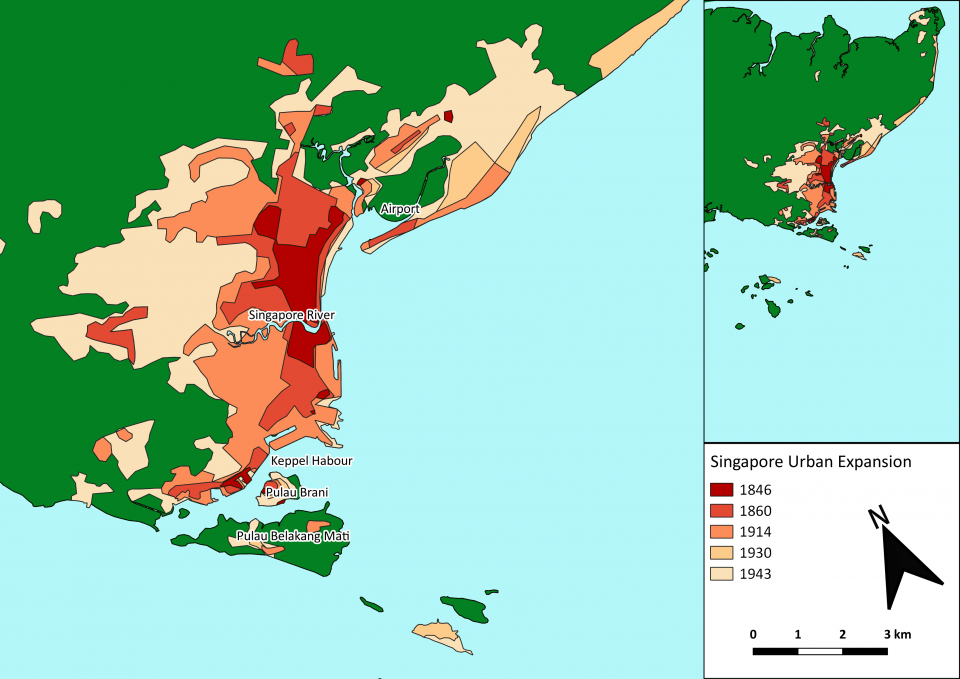

Development of port infrastructure was massive over the next decades. Thus by the 1930s, the port’s operational landscape covered some 23,000 acres, encompassing the Singapore River, Telok Ayer Basin and, in honor to its surveyor, Keppel Harbour.

Map of colonial Singapore’s urban growth.

Map of colonial Singapore’s urban growth.

© Felix Mauch and David Stäblein, n.d.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

Singapore’s land reclamation strategy has never been about pure urban growth, but the strategic expansion of logistical space. The constant dredging and reshaping of unruly ecologies, however, came at a cost. It eradicated indigenous livelihoods, exploited migrant labor, and consumed more-than-human environments. This colonial theft via terraforming, Charmaine Chua reminds us, was at the very center of Singapore’s story of logistical ecologies and, by extension, the global supply chains flowing through the island.

The telos of the logistics city was efficiency and to “improve trade” by minimizing times of transit as well as optimizing urban space and natural environments. For Singapore, “a small country with no natural resources” according to the memoirs of its first post-independent prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, the point has always been moving the goods. Not making them.

As a consequence, the vast storage spaces, godowns, and freight facilities the colonial state clustered around the ports of Singapore produced their own spatiality: distinct urban environments, hyper-engineered for commerce and the seamless handling of commodities. Migrant workers and local communities, however, seldom gained access to the logistical landscapes they were forced to build—except perhaps to maintain their infrastructure.

How to cite

Mauch, Felix. “Logistical Ecologies. A Singapore Story.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2021), no. 30. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9358.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Felix Mauch

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Amrith, Sunil S. Crossing the Bay of Bengal: The Furies of Nature and the Fortunes of Migrants. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Barnard, Timothy B., ed. Nature Contained: Environmental Histories of Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press, 2015.

- Barua, Maan. “Infrastructure and Non-human Life: A Wider Ontology.” Progress in Human Geography (11 February 2021). doi:10.1177/0309132521991220

- Cowen, Deborah. The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global TradeTrade. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

- Larkin, Brian. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 327–343.

- Powell, Miles A. “Singapore’s Lost Coast: Land Reclamation, National Development and the Erasure of Human and Ecological Communities, 1822–Present.” Environment and History (6 September 2019). doi:10.3197/096734019X1563184692871

- Yew, Lee Kuan. The Singapore Story: Memoirs. Singapore: Times Editions, 1998.