In the heart of the South Indian city of Bangalore (capital of the state of Karnataka), and behind its well-known indoor stadium, is a tiny, nondescript water body that is largely ignored for much of the year. Once a year, during the city’s oldest festival (known as the Karaga, and celebrated by the Vanhikula Kshatriyas, a community of horticulturists), the water body becomes a site of celebration, visited by thousands of devotees. For the rest of the year, the lake is frequented only by a few people, such as a fisherman who harvests small fish, sharing a portion with a circling Brahminy kite (Haliastur indus) (Figure 1). This small water body is the only remnant of what was, a century ago, one of Bangalore’s largest and most prominent lakes, Sampangi Lake, which constituted a major part of the city’s water supply.

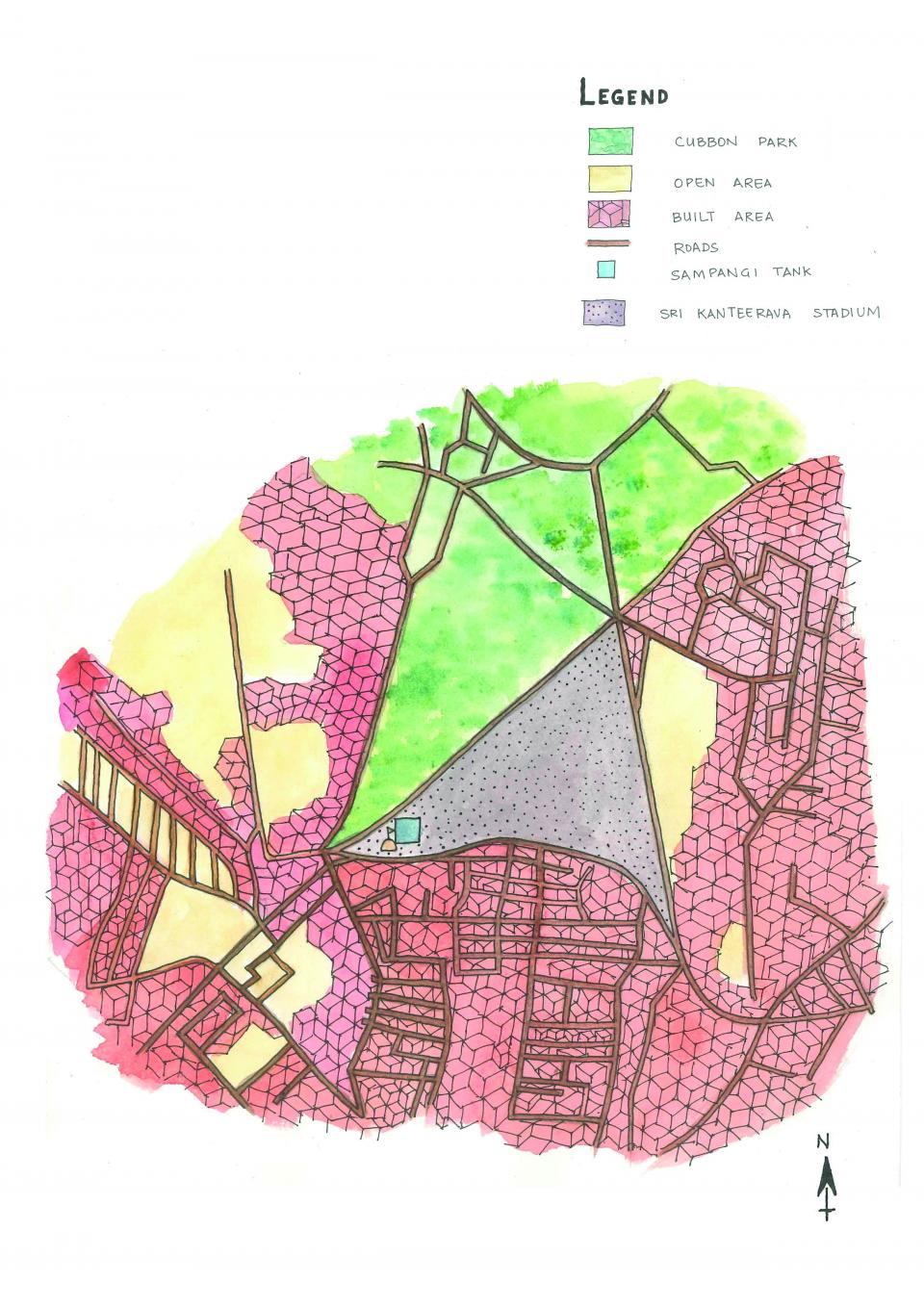

In the late nineteenth century, Bangalore was divided into two jurisdictional regions: the British Cantonment, ruled by the Residency, and the native city or Pete, governed by the Mysore kings. Sampangi Lake was an important water source for both zones by virtue of its central location. Land use changed rapidly between 1885 and 2014, with rapid urbanization and the shrinking of the lake, leaving behind only the rectangular tank described above (Figures 2 & 3).

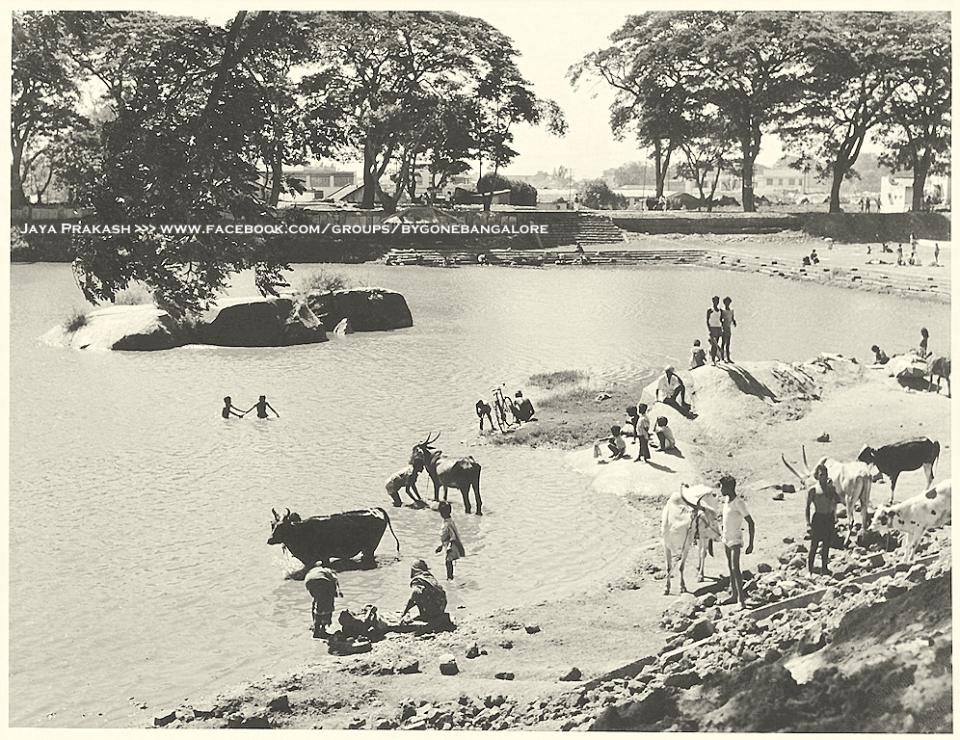

Oral histories of elderly residents indicate that the lake acted as an urban commons, supplying water for drinking and domestic uses, and supporting horticulture, fishing, brick making, laundering, and pastoralism at least until the mid-1930s (Figure 4).

Another very different group of users found this lake valuable, as it enhanced the neighborhood’s aesthetic and recreational value. These were British residents: owners of lakeside bungalows, polo players, and those walking around the lake for recreation. Conflicts arose between these different users. British polo players asked the colonial government to drain the lake so they could play polo on the lakebed. The British Resident also considered draining the lake to save the adjacent bungalows and brewery, which supplied colonial troops with supplies of beer, from flooding. In response, 49 horticulturists (Vanhikula Kshatriyas) petitioned the Mysore king, pleading that the loss of water would affect their orchards.

Despite the Mysore king writing in favor of the local horticulturists, the lake was eventually drained and used to play polo in the early twentieth century. The British crown was politically dominant. Local livelihoods such as brick making were banned because these created unsightly pits. Peons were employed to guard entry to the lake, restricting the access of local communities of fishers and washers. These communities migrated away from Sampangi Lake to other parts of the city. New communities of weavers immigrated into the neighborhood and filled this gap, practicing livelihoods that were not dependent on ecosystem services from the lake.

Another contributing factor to the decline of the lake was the fact that by the late nineteenth century Bangalore had begun to receive piped water from the distant Hesarghatta Reservoir. Sampangi Lake no longer represented an essential water source for the city. Water from the lake was later diverted into a new reservoir, the Sankey Tank towards the north, further reducing the volume of water available in the Sampangi Lake.

With traditional users migrating away from the lake and new populations settling in, the lake began to be perceived as a hazard to life (on account of incidents of drowning), and a health hazard. Urbanization, increase in land prices, and a change in perception of the utility of the lake catalyzed its conversion into a built-up space. As Bangalore grew into a twentieth-century city with an aspirational modern identity, the lakebed was converted into the Sri Kanteerava indoor sports stadium. The landscape around Sampangi now retains little of its former ecological and social importance. Only the small rectangular tank of water remains, because of its centrality to the Karaga festival.

Fig. 5. Sri Kanteerava Indoor Stadium in 2012

Fig. 5. Sri Kanteerava Indoor Stadium in 2012

Photograph by Sanyam Bahga. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Many other lakes within Bangalore have also been impacted by urbanization: they now form parts of bus terminals, hockey stadiums, malls, and residential layouts. Where lakes have survived into the present, restoration efforts almost inevitably exclude the utilitarian uses of the water body by brick makers, farmers, and grazers, who still derive sustenance from these resources. This exclusion creates a disconnect from the resource, which translates into indifference on the part of these lake users. As one of our interviewees put it, “The government has erected a fence around the water body to keep us out. Why then should we go in there or even be worried about what happens to the lake?”

The pattern observed in Sampangi Lake, where aesthetic and recreational perspectives are prioritized over utilitarian uses as representative of the importance of lakes, continues even today. However, as our research has shown, the long-term sustainability of these resources depends largely on their continued accessibility as an urban commons, with utilitarian as well as recreational value. In order to build socially inclusive and ecologically sustainable cities, we must look to forgotten stories of the past such as that of Sampangi lake, and understand the historical contingencies that were important for the survival of urban commons, in order to shape more inclusive, ecologically oriented strategies for urban sustainability in the cities of India and the Global South today.

How to cite

Unnikrishnan, Hita, and Harini Nagendra. “The Lake That Became a Sports Stadium.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2018), no. 23. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8282.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 Hita Unnikrishnan & Harini Nagendra

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Mundoli, Seema, Hita Unnikrishnan, and Harini Nagendra. “The ‘Sustainable’ in Smart Cities: Ignoring the Importance of Urban Ecosystems.” DECISION 44, no. 2 (June 2017): 103–20.

- Nagendra, Harini. Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Unnikrishnan, Hita, Seema Mundoli, B. Manjunatha, and Harini Nagendra. “Down the Drain: The Tragedy of the Disappearing Urban Commons of Bengaluru.” South Asian Water Studies 5, no. 3 (May 2016): 7–11.

- Unnikrishnan, Hita, B. Manjunatha, and Harini Nagendra. “Contested Urban Commons: Mapping the Transition of a Lake to a Sports Stadium in Bangalore.” International Journal of the Commons 10, no. 1 (2016): 265–93.

- Srinivas, Smriti. Landscapes of Urban Memory: The Sacred and Civic in India’s High Tech City. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan, 2004.