In 1823, a new disease—cholera—visited the Russian Empire for the first time. It was initially discovered in the south of the Empire, in Astrakhan. In 1830, the epidemic broke out in Moscow, and it reached the capital, St. Petersburg, in 1831.

An English caricature of the nineteenth century shows “Cholera” rowing along the polluted river Thames amid sewage and dead rats (1858).

An English caricature of the nineteenth century shows “Cholera” rowing along the polluted river Thames amid sewage and dead rats (1858).

Punch Magazine, 1858.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This first cholera epidemic began on 14 June and did not end until 5 November. According to official figures, 12,540 people fell ill in St. Petersburg during that time, with a death toll of 6,449.

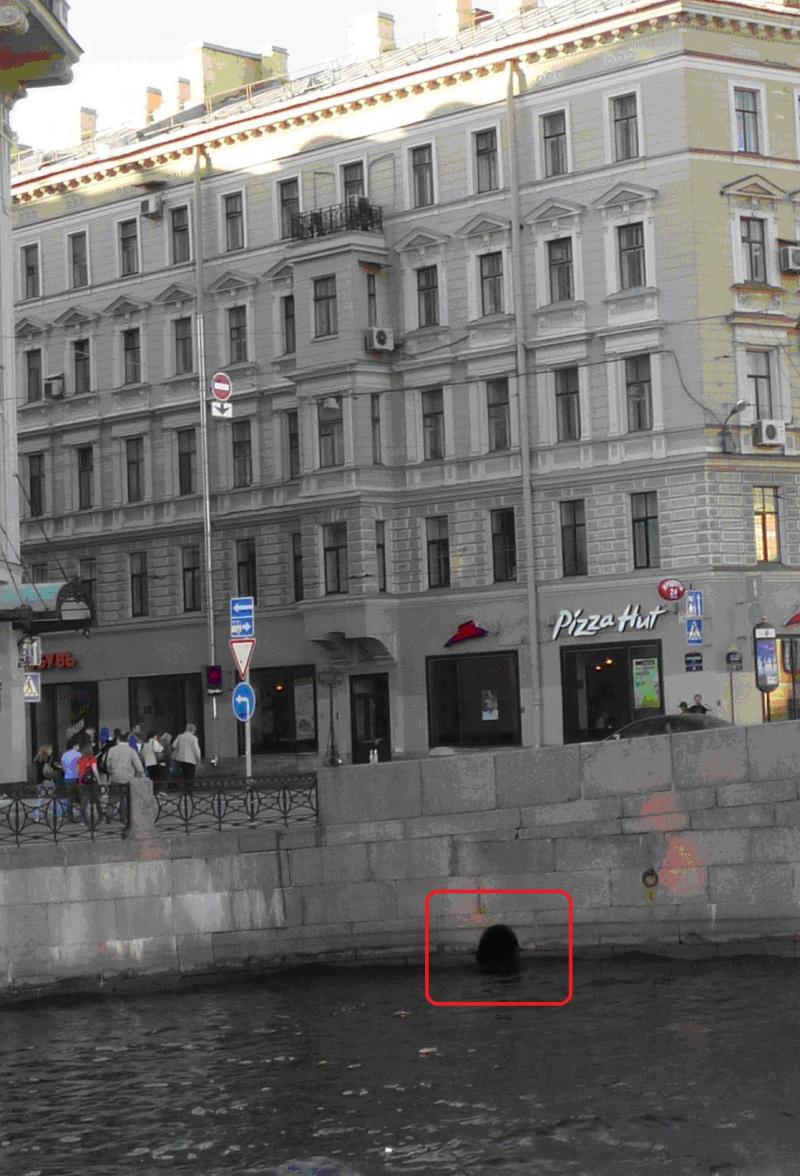

Culvert on the river Moika

Culvert on the river Moika

2011 Kseniia Barabanova

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The wide dissemination of the disease was brought about by the poor sanitary conditions of the city. Water from the rivers and canals was particularly dangerous. The canals, constructed in order to divert floodwater, were used both for disposing of sewage and for household water needs. Cesspools were frequently located in close proximity to wells, so that well water was a particular danger to public health. The cesspools were not emptied on a regular basis, and this also facilitated the rapid spread of cholera.

Physicians advised the city’s inhabitants not to use spoiled ingredients in food preparation. Most of the population bought their food at markets, such as that at Sennaya Square, which the actor Petr Karatygin called “the Petersburg cesspool.” It was also here that the infamous cholera riot of June 22, 1831 broke out because of growing social tensions between the poor people, who were most affected by the epidemic, and the educated classes. The unsanitary condition of the markets, slaughterhouses, and stores remained an important factor in the problem of spreading cholera.

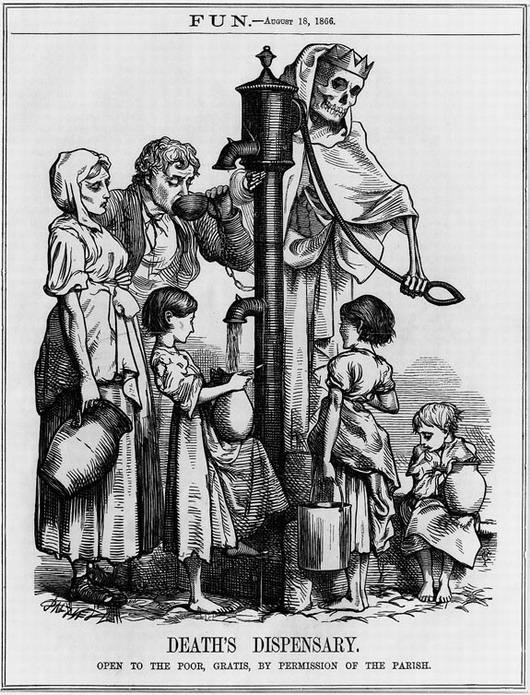

“Death’s Dispensary”: This caricature published during the London cholera epidemic of 1866 was a response to the hypothesis of the English epidemiologist John Snow, who linked the cholera epidemic with sewage seeping into ground water used for drinking (1866).

“Death’s Dispensary”: This caricature published during the London cholera epidemic of 1866 was a response to the hypothesis of the English epidemiologist John Snow, who linked the cholera epidemic with sewage seeping into ground water used for drinking (1866).

Drawing by George John Pinwell, 1866.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Marketplaces were not the only places where disease easily gained a foothold. Frequent flooding also contributed to the unsanitary state of the imperial capital as a whole. The effects of the flood of 1824 were visible well into the 1830s. Washed-out streets, the ruined Smolensk cemetery and other damaged facilities aided the development of the first cholera epidemic. On the other hand, the storm of 20 August 1831 hastened the end of the epidemic: contemporaries reported that the city was “cleansed,” and there were fewer cases of disease thereafter. This first cholera epidemic indicated the existence of sanitary problems in the city, but no solution was found; cholera became a frequent visitor to nineteenth-century St. Petersburg, where it remained the most fearful epidemic disease of the century.

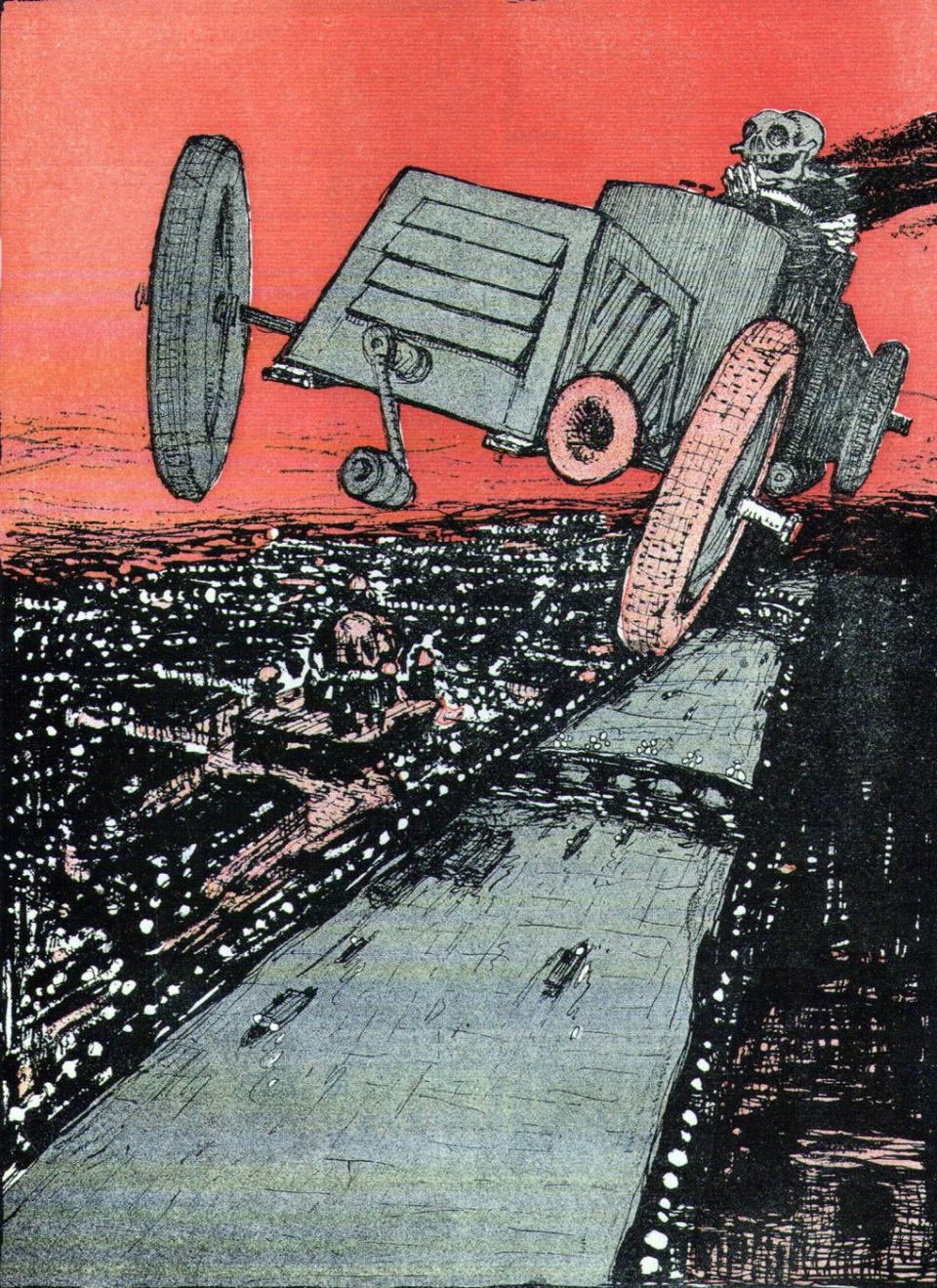

The nightmare of Petersburg (1908)

The nightmare of Petersburg (1908)

Drawing by Re-Mi. Satirikon magazine, 1908.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

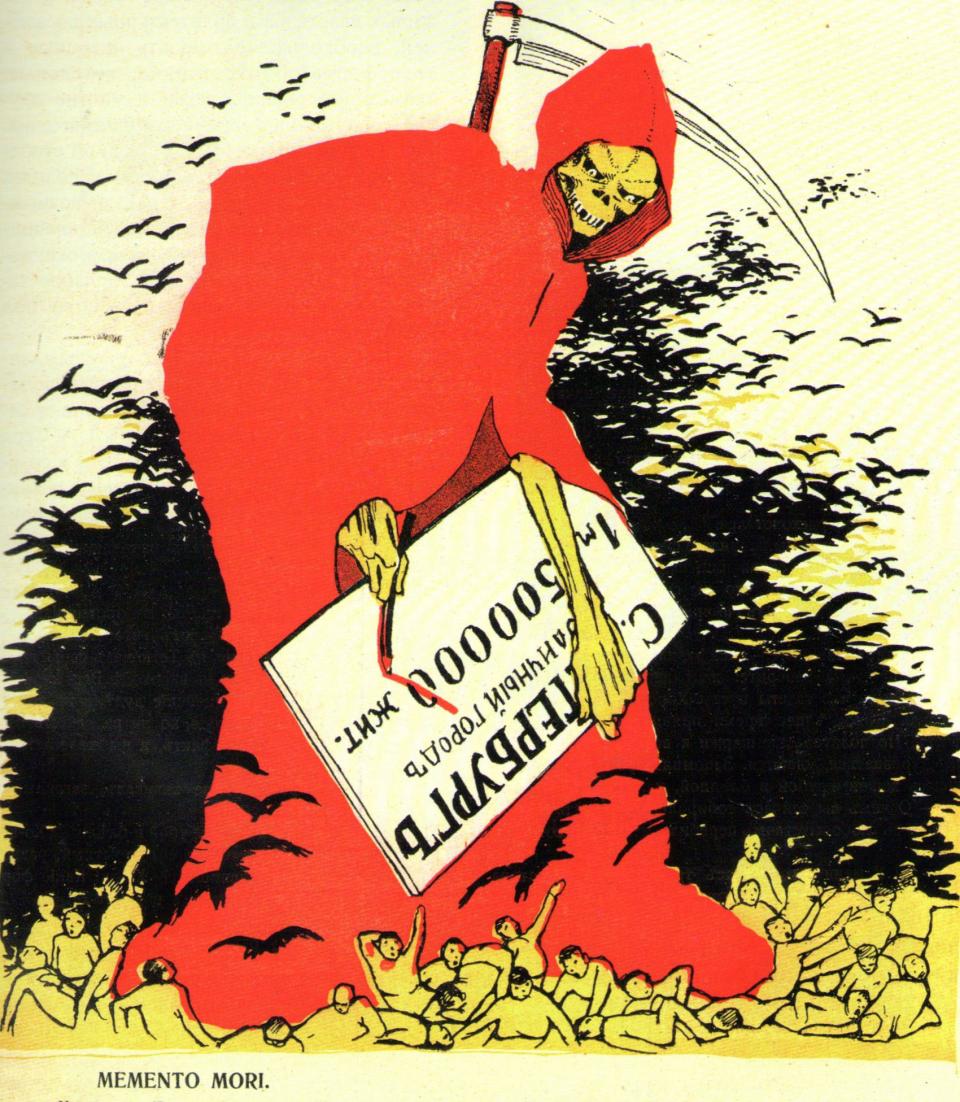

Memento Mori

Memento Mori

Drawing by A. Iunger. Satirikon magazine, 1909.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

How to cite

Barabanova, Kseniya. “The First Cholera Epidemic in St. Petersburg.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2014), no. 6. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5385.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2013 Kseniya Barabanova

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Arkhangel'skii, Gregorii Ivanovich. Kholernye epidemii v evropeiskoi chasti Rossii v 50-ti-letnii period 1823–1872 gg. St. Petersburg: Tip. M Stasi u levicha, 1874.

- Karatygin, Petr A. Kholernyi god. 1830–1831. St. Petersburg: Tip. M. Stasi u levicha, 1887.

- Lapin, Vladimir V. Peterburg. Zapakhi i zvuki. St. Petersburg: Evropejskij Dom, 2009.

- McGrew, Roderic E. Russia and the Cholera, 1823–1832. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.

- Nikitenko, Aleksandr V. Dnevnik (1826–1877) Vol. 1 . Leningrad: Gos. izd-vo khudozh. lit-ry, 1955.

- Pavlovskaia, L. Kholernye gody v Rossii. St. Petersburg: Izd. K. L. Rikkera, 1893.