The Irish Sea which separates Great Britain and Ireland has often been written about in terms of divisions, threats, and hazards. Facing each other across that sea, the coast of Wales and Ireland’s eastern seaboard have a more complex story to tell, one characterised by intimate if troubled lines of connection. A place of passage for centuries, the Irish Sea has a distinct identity, its memory longer and more capacious than borders or polities. The region ties together port communities that differ in their stories, cultures, and worldviews. This article explores themes of division and connection across coasts through the story of the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Leinster, a British mail steamer that was torpedoed just off the coast of Ireland as World War I neared its end and the Irish War of Independence began to stir.

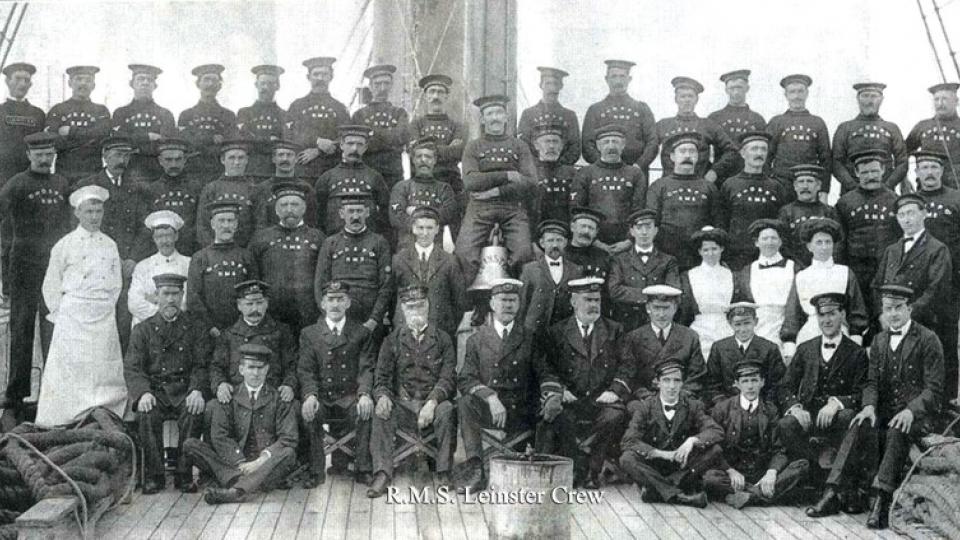

A pre-war portrait of the crew onboard RMS Leinster. The “CoDSPC” uniform marking suggests that crew frequently moved between the four ships of the company, particularly when one was undergoing maintenance. With permission from Holyhead Maritime Museum, c. 1914.

A pre-war portrait of the crew onboard RMS Leinster. The “CoDSPC” uniform marking suggests that crew frequently moved between the four ships of the company, particularly when one was undergoing maintenance. With permission from Holyhead Maritime Museum, c. 1914.

Courtesy of the Holyhead Maritime Museum.

© Holyhead Maritime Museum.

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

When the Leinster left port on the morning of 10 October 1918, the weather at Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) was fine. The sea though remained choppy from previous storms, promising a rough crossing to Holyhead. She could make the journey in only 2.5 hours but weather and wartime conditions often meant a longer crossing. Just an hour after having left Kingstown, with the vessel yet to clear Dublin Bay, the ship was torpedoed by German submarine SM UB 123. According to the latest casualty count, 569 of the 771 people on board died, still the largest loss of life in a single event in the Irish Sea. With the Leinster, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company (CoDSPCo) lost a second vessel, the RMS Connaught having sunk in a war-related accident a year earlier. The company never recovered from their wartime losses and went out of business in 1922.

A naval portrait of RMS Leinster showing the vessel in peacetime. Oil on canvas; H 43.5 x W 83.5 cm, 85/205/1, 1900.

A naval portrait of RMS Leinster showing the vessel in peacetime. Oil on canvas; H 43.5 x W 83.5 cm, 85/205/1, 1900.

© R. Waring, 1900.

Courtesy of the Holyhead Maritime Museum.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Shock was felt in Ireland and Wales alike. The vessel torpedoed and sunk that day was one among a small fleet of ships supplying the mail between Kingstown and Holyhead, a route in regular use since 1848. The CoDSPCo vessels served as sorting offices on the sea with clerks and crew traditionally hired from the Holyhead and Kingstown communities. The mailboats also carried soldiers and civilians who availed of regular and well-connected crossings well into the twentieth century.

RMS Leinster. Project funded by Geological Survey of Ireland and Infomar. This data was collected as part of a collaborative survey between INFOMAR and Ulster University. Full wreck sheet is available from http://web.archive.org/web/20180413175355/http://www.infomar.ie/data/Shipwrecks/Box50/pdfs/RMSLeinster_Final.pdf. 3D Model by Pete Corrigan, 9 October 2018, via Sketchfab.

Rescue boats were dispatched from Kingstown and survivors of the Leinster brought to hotels in Dublin. For weeks, bodies were found washed ashore not only in Ireland, but across the sea in Wales. Irish writer Katharine Tynan stayed in Dublin’s Shelbourne Hotel in the days after the loss of the Leinster and later recalled the “dreadful” atmosphere with “the corridors full of the unclaimed luggage of those who had gone across for the week-end intending to return.” In Tynan’s description, “the sea was giving up its dead daily and hourly during that week.” The story resonated with the longer history of lives and vessels lost in the Irish Sea and the wreck became part of what Gillian O’Brien has described as the “ring of sorrow” encircling Ireland, “binding together communities who have suffered maritime tragedies like beads on a rosary.” Sea creatures suffered too: contemporary newspaper reports describe machine gun attacks on whales that were mistaken for submarines as well as sea mammals killed when they swam into mines. In the memory of Irish modernist Elizabeth Bowen, broadcast on the BBC during World War II, the loss of the Leinster exposed “the cleft … between the two islands,” a “natural tract of danger” at once political and environmental, its vulnerability intensified by conflict.

RMS Leinster. Project funded by Geological Survey of Ireland and Infomar. This data was collected as part of a collaborative survey between INFOMAR and Ulster University. Full wreck sheet is available from http://web.archive.org/web/20180413175355/http://www.infomar.ie/data/Shipwrecks/Box50/pdfs/RMSLeinster_Final.pdf. 3D Model by Pete Corrigan, 9 March 2015, via Sketchfab.

The material and cultural life of the wreck serves as a bio-regional case study mingling diverse currents of affect, culture, and memory. The hulls of World War I wrecks found on the floor of the Irish Sea basins make them ideal habitats for marine species, including large shoals of pouting, pollack, and bib as well as wrasse and conger eels in the holes and plumose anemones on the sides. The site is regularly visited by experienced divers keen to explore its rich marine environment, despite strong tidal currents, difficulties of navigation in poor visibility, and its location on the path of passenger ferry crossings. The stable structure, good supply of food, and complex environment of these “artificial reefs” means that wrecks continue to exert agency below the waves, just as their passage above the surface and subsequent sinking shaped infrastructural, environmental, political, and social ecologies on the Irish Sea. The growth of marine life on the Leinster and the equally slow accretion of memorialisation in the community have transformed military and social tragedy and merged it with environmental history. The material and cultural traces of the wreck have become part of the intangible and underwater cultural heritage of the Irish Sea, categories protected under key 2001 and 2003 UNESCO conventions.

Preferring hard surfaces to grow on as part of their habitat, plumose anemones densely cover many of the ship wrecks in the Irish Sea. Metridium dianthus (Ellis, 1768), Common Name: Plumose anemone, Taxonomy: Animalia :: Actiniaria :: Metridiidae.

Preferring hard surfaces to grow on as part of their habitat, plumose anemones densely cover many of the ship wrecks in the Irish Sea. Metridium dianthus (Ellis, 1768), Common Name: Plumose anemone, Taxonomy: Animalia :: Actiniaria :: Metridiidae.

© Bernard Picton, 13 September 2016.

Courtesy of iNaturalist UK.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The Irish Sea is defined not only by its coasts or the maritime routes that crisscross its surface, but by lives, vessels, and material objects lost at sea. Its notoriously changeable conditions have claimed centuries of lives and swallowed up countless vessels. While the sinking of the Leinster is often remembered as a singular episode in the history of global conflict, it also forms part of a more extensive environmental narrative that reaches back to the beginnings of the British infrastructure state and continues forward as the complex forms of biodiversity found on the ocean floor.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed as part of the Ports, Past and Present project, funded by the European Regional Development Fund through the Ireland Wales Cooperation program.

How to cite

Connolly, Claire, Rita Singer, and James L. Smith. “Environmental Dimensions of the RMS Leinster Sinking.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2021), no. 32. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9370.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Connolly, Claire, Rita Singer, and James L. Smith

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Bowen, Elizabeth. “A Year I Remember.” In Listening In: Broadcasts, Speeches, and Interviews by Elizabeth Bowen, edited by Allan Hepburn, 63–76. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010, p. 72.

- Connolly, Claire. “Turbulent Water: A Cultural History of the Irish Sea.” Irish Times, May 4, 2019. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/turbulent-water-a-cultural-history-of-the-irish-sea-1.3864668.

- Lecane, Philip. “The Sinking of the RMS Leinster: The International Significance.” History Ireland: 20-Century / Contemporary History 12, no. 1 (Spring 2004). https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/the-sinking-of-the-rms-leinster-the-international-significance.

- Mulhall, Ed. “’The Great Day’ - Katharine Tynan & the Mother’s War.” Century Ireland Project. Accessed November 17, 2021. https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/the-great-day-katharine-tynan-the-mothers-war.

- O’Brien, Gillian. The Darkness Echoing: Exploring Ireland’s Places of Famine, Death and Rebellion. Dublin: Doubleday Ireland, 2020.

- Singer, Rita. “Responses to the Sinking of the Leinster.” Ports, Past and Present. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://portspastpresent.eu/items/show/474.

- Tynan, Katharine. The Wandering Years. London: Constable, 1922.