Scarborough Beach, 14 kilometers north of central Perth, Western Australia, is well known for its white sands, beach culture, and vibrant nightlife. Just beyond those bright lights is the coastal foreshore, unique in its progression from mobile and stable sand dunes to tuart/banksia woodlands. Over the course of 80 years, the condition of this coastal dune system became entangled with the hopes and dreams of its human residents as it faced continuous encroachment from successive development proposals, like much of the global coastal-urban environment. Its ultimate protection from development in 2019 after over 35 years of struggle demonstrates the power of local advocacy to effect change. Yet the far greater force of climate change is now impacting on the coastline, as the effects of wind and tide necessitate new guidelines for a managed retreat.

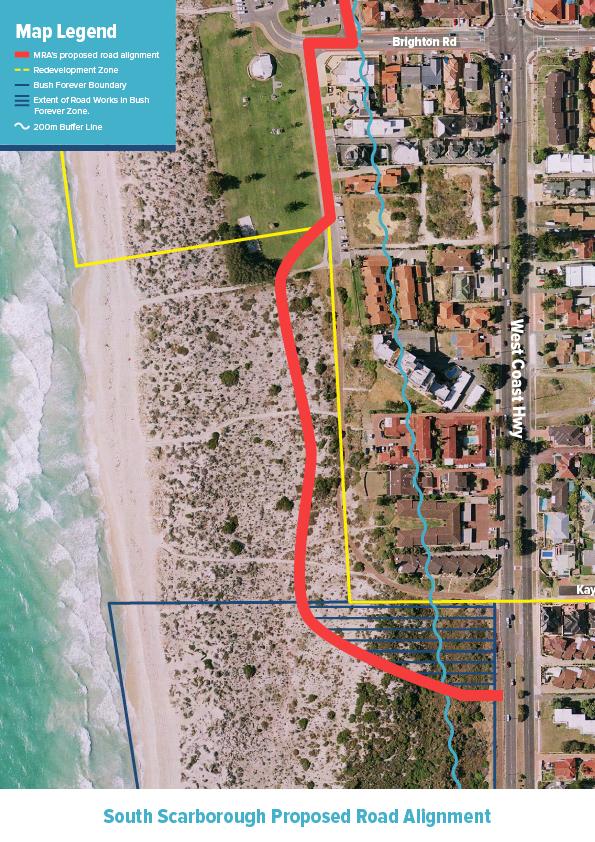

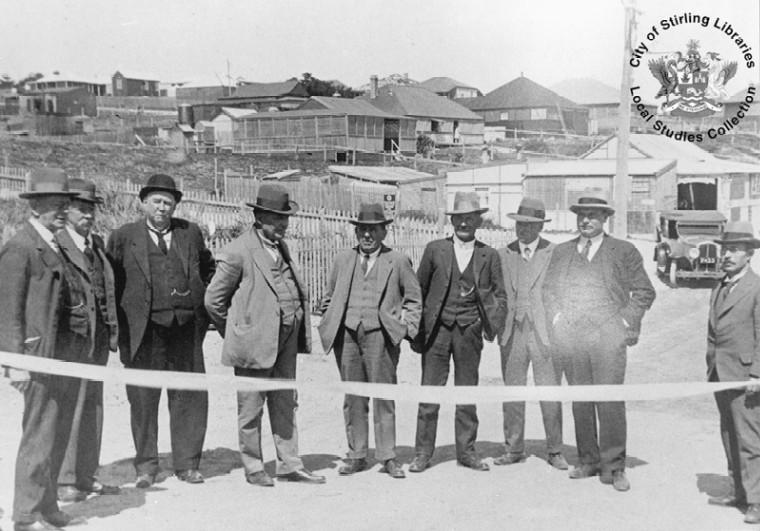

The first land parcel in Scarborough Beach was granted in 1869, continuing the dispossession of lands that had sustained the Nyoongar people for tens of thousands of years. By 1932 the first physical transformation of the coastal dunes occurred when a section was removed during the construction of the bituminized road called The Esplanade.

Official opening of the Esplanade, 1932

Official opening of the Esplanade, 1932

Unknown photographer, 1932.

Courtesy of the City of Stirling Libraries, Local History Collection.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the influx of companies mining nickel, petroleum, bauxite, natural gas, and alumina fuelled the development of Perth’s first skyscrapers. Quietly, behind the high-rises, a growing recognition of the importance of Perth’s coastal dunes was also emerging, fostering new groups focusing on environmental issues in their own local areas. In Scarborough conservationists and local residents formed the Trigg Dune Heritage Group, enlisting well-known scientists and support from the Conservation Council of WA. Their efforts resulted in the identification of Trigg Bushland at the northern end of Scarborough Beach (known as the Trigg Regional Open Space) in 1981.

It was a positive first step. However, much more development was just over the horizon. By 1984 the proposal for Scarborough’s first 24-story tower was proposed by developer Alan Bond, seeking to convert the white sand beachfront into Australia’s premier entertainment precinct. In 1985 plans were released to extend a four-lane road through the Trigg Bushland. Although the Trigg Dune Heritage Group had laid a foundation for the campaign, the pro-development ethos was too strong. Both the tower, now called the Rendezvous Hotel, and the road were built. By 1992 Alan Bond was declared bankrupt and jailed, while the “WA Inc” scandal involving corrupt dealings between business and the Labor Premier Brian Burke was revealed.

Bond’s Observation City Hotel, Scarborough Beach, 1987.

Bond’s Observation City Hotel, Scarborough Beach, 1987.

Photograph by Rennie Ellis, 1987.

© Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

Courtesy of the State Library Victoria, H2012.113/202.

Click here to view image source.

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Scarborough Beach and the Rendezvous Hotel, 2010.

Scarborough Beach and the Rendezvous Hotel, 2010.

Photograph by Michael Spencer, 2010.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 11 May 2021. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Meanwhile, local advocacy groups continued to push for protection. In 1989 conservationists succeed in securing 122 hectares of coastal bushland—but not the dunes—into a Class A Reserve. New groups sprung into action. Friends of Trigg Bushland group incorporated in 1980, aiming to undertake bush regeneration in the area and lobby for permanent protection of the coastal dunes. By 1998 the 10 hectares of dune were vested in the City of Stirling for conservation and recreation purposes and designated a Bush Forever Reference Site. By 2001 the City of Stirling announced the abandonment of the road proposal and amalgamation of land into the reserve.

Yet again, however, the promise of development won out. By 2014 the Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority (now DevelopmentWA) halted the protection process, proposing an eighteen million Australian dollar road extension in 2016. Images of the works gouging a swath of bitumen through the dunes sparked outrage.

Local advocates regrouped and built a strong coalition to lobby against the proposal. In 2016 the Beach Not Bitumen campaign was launched, a network of groups active in Scarborough and across the greater Perth region: Save our Sand Dunes, Friends of Trigg Beach, Friends of Trigg Bushland, Urban Bushland Council, the Wildflower Society of WA, and WA Conservation Council. The network campaigned together, holding rallies on the dunes and outside WA Parliament House, crowdfunding over ten thousand Australian dollars, organizing community forums, and collecting four thousand signatures for an anti-road extension petition.

Yet again, success seemed on the horizon when permanent protection for the site was given a year later in 2017. And yet again another development application to clear dune habitat was proposed, this time as part of a 10-story development approved by the MRA and incongruously called “The Beach Shack.” Beach Not Bitumen continued their campaigning until finally, by 2019 the application was withdrawn and the dunes fully encompassed within the South Trigg Class A Reserve. After almost 40 years of community effort, this unique coastal dune ecosystem had been protected.

The long campaign to protect the coastal dunes of Scarborough Beach is one of many hundreds of local, grassroots efforts against rapacious development across Australia. Yet these campaigns may not be enough to save coastal dunes from our changing climate. The story of the Scarborough dunes mirrors that of other socio-natural sites, where the humans shape the dunes yet remain at the mercy of unstoppable coastal processes. Coastal erosion continues to threaten development all along the Western Australian coastline, with Scarborough Beach one of five Perth beaches at serious risk. In some instances, modeling indicates that beaches (such as Lancelin, 120 kilometers north of Perth) will lie one hundred to two hundred meters further inland than today.

The Esplanade extension, had it been built, would eventually have been gifted to the sea. In 2017 the WA Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage drafted their Planned and Managed Retreat Guidelines, formalizing the removal of public infrastructure and abandonment of private property when access is cut off. Ultimately, waves and wind will have the last say.

How to cite

Gulliver, Robyn. “Development or Dunes? The Long Struggle to Protect Perth’s Scarborough Beach Coastal Reserve.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2021), no. 20. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9309.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Robyn Gulliver

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Bolton, Geoffrey Curgenven. Land of Vision and Mirage: A History of Western Australia since 1826. Crawley: University of Western Australia Press, 2008.

- Danaher, Mike. “Reconciling Foreshore Development and Dune Erosion on Three Queensland Beaches: An Historical Perspective.” Environment and History 11, no. 4 (2005): 447–74.

- de Freitas, Joana Gaspar. “Making a Case for an Environmental History of Dunes.” Anthropocenes—Human, Inhuman, Posthuman 1, no. 1 (2020): 5. doi:10.16997/ahip.4.

- Gangaiya, P., A. Beardsmore, and T. Miskiewicz. Who Cares about Coastal Dunes and Vegetation Now? Wollongong, NSW: Wollongong City Council, 2013.

- Gulliver, Robyn, Kelly S. Fielding, and Winnifred Louis. “The Characteristics, Activities and Goals of Environmental Organizations Engaged in Advocacy within the Australian Environmental Movement.” Environmental Communication 14, no. 5 (2020): 614–27. doi:10.1080/17524032.2019.1697326.

- Hutton, Drew, and Libby Connors. History of the Australian Environment Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Winiwarter, Verena, and Martin Schmid. “Socio-Natural Sites.” In Concepts of Urban-Environmental History, edited by Sebastian Haumann, Martin Knoll, and Detlev Mares, 33–50. De Gruyter, 2020.