The lakes of Lapsista and Ioannina (also known as Lake Pamvotis) used to comprise a unified ecosystem and a significant hydrological unit, which included swampy areas rich in biodiversity. When Lapsista was drained to make way for agricultural development during the 1950s, a key part of the area’s rich ecosystem was lost and the basin’s landscape was permanently altered.

For the people of the area, the wetlands of the two lakes were always a source of natural wealth, carrying them through the toughest historical conditions. The basin and the wetland seemed to provide enough to allow for relative prosperity through small-scale agriculture, fishing, hunting, and stockbreeding.

The minister of public works, Konstantinos Karamanlis, inaugurates the commencement of the drainage works in Lapsista, 2 August 1954.

The minister of public works, Konstantinos Karamanlis, inaugurates the commencement of the drainage works in Lapsista, 2 August 1954.

© Christos Anastasiou. All rights reserved. Courtesy of the “Konstantinos G. Karamanlis” Foundation.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Lapsista was no stranger to land-improvement works intended to create segments of arable ground; neither was it a stranger to attempts to drain it partially or completely. An example would be the drainage works of 1872. Under Ottoman rule, landowners along with the commander of Ioannina and his representative proceeded to drain the 10 large agricultural properties of the area in order to prevent damages caused by seasonal floods. Historically, these interventions had limited scope and impact, or they failed due to abandonment. Plans to permanently drain the lake were once again laid out during the 1930s under the rule of Ioannis Metaxas but were quickly set aside in the wake of the Second World War. After being seemingly forgotten for years, these plans were finally brought to light and implemented in 1954, following the dictates of the Great Acceleration. Unlike previous attempts, modernization provided the technological means to finally implement a project that promised not only to improve crop production but also to eliminate the relatively few cases of malaria in the area. The wetland of Lapsista, and consequently that of Ioannina, would experience ecocide. The natural functional system of the two lakes, comprising of a complex network of sinkholes, streams, and springs, was severely damaged. The geomorphology of the landscape was altered in a way that affected human and nonhuman life at many levels. The promised benefits to agriculture and health were, at the very least, disappointing. Lapsista’s now “blasted” landscape is one of vast and inefficient monocultures, sustained only through heavy fertilizing and consistent pesticide treatment.

Several links can be traced between this ecological disaster and the ailing, present-day Lake Pamvotis. However, many anthropogenic factors ensure its continuing degradation. Despite scientific recommendations and activist demands, regional and state authorities have prioritized development actions with complete disregard for the sustainability of the ecosystem.

In 1969, the levee of Anatoli-Katsika was constructed, followed by that of Perama-Amfithea. The preparatory studies for the former suggested the delimitation of the lake along its natural boundaries, but the levee was constructed further inside, isolating Pamvotis from its large wetland. The Lake of Ioannina continued to endure its severance from some of its most vital components. In this transition, the waterbody began to be managed as an irrigation reservoir. As far as the state was concerned, this became its only purpose despite legislation regarding its status as a protected area.

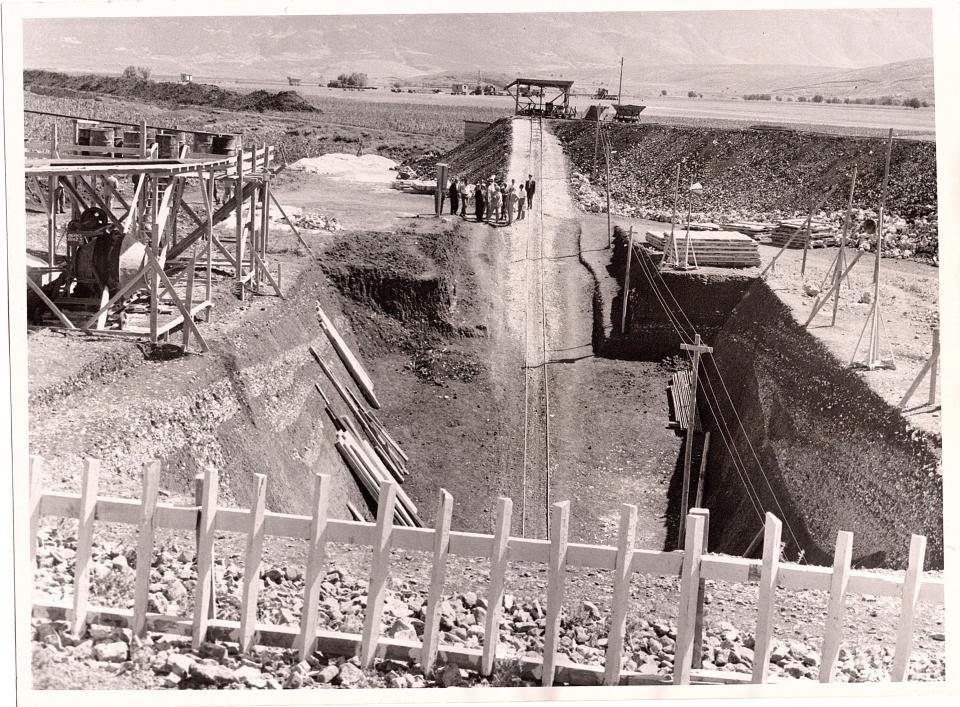

General view of the ongoing drainage works in Lapsista, after the inauguration of the second phase of the works by Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis, 20 July 1957.

General view of the ongoing drainage works in Lapsista, after the inauguration of the second phase of the works by Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis, 20 July 1957.

© Christos Anastasiou. All rights reserved. Courtesy of the “Konstantinos G. Karamanlis” Foundation.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In November 1976, the Ioannina Environmental Protection Association (Sullogos Prostasias Periballontos Ioanninon, hereby IEPA) was established with the sole purpose of protecting the environment of the basin of Ioannina. The IEPA was the first organized movement in the region to stand against human impacts on the local environment.

The 1990s saw the abandonment of agriculture, and farming land around Pamvotis was turned into residential and industrial areas. During the years that followed, many attempts were made by state actors to delimit the lake on the constructed levees rather than the lake’s natural boundaries, and many times associations such as the IEPA have objected officially, arguing that these actions would have disastrous consequences for both the ecosystem and the people of the basin.

Disputes over the delimitation of the lake were never settled, and its protection remains a secondary matter to those in positions of power. Sources on the history of lakes in urban surroundings suggest that the waterbodies have played a significant role in the cultural and ecological history of cities. As in the present case, however, urbanization and industrialization have had major impacts on the health and water quality of urban lakes, with increased pollution, sedimentation, and other processes affecting their ecological and cultural value. In order to understand their history and ecology, it is important to consider the significance of interdisciplinary research as well as the perspectives of different stakeholders in achieving conviviality. While the need for sustainable management and restoration practices is apparent, let us never forget that, as Arturo Escobar put it, the crisis we face is civilizational. If the tools that modernity has produced are insufficient for the tasks at hand, the only viable course of action necessitates a radical break from conventional practices, such as those long advocated by various development discourses.

How to cite

Perrakis Kollias, Petros. “Development and Degradation in the Lakes of Lapsista and Ioannina from the 1950s to the Present.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2023), no. 14. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9652.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2023 Petros Perrakis Kollias

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018. doi:10.1215/9780822371816.

- Katsikis, Apostolos. “Pamvotidos Afigisis”: I Limni ton Ioanninon kai i sxesi tis me tin poli [“Pamvotis Narration”: The Lake of Ioannina and its relation to the city]. Ioannina: Municipality of Ioannites, 1996.

- Katsougiannopoulos, Vasilios Chr. 1989. I Igis tis Pamvotidos: Erevna ton Igiinologikon kai Perivallontikon Provlimaton tis limnis ton Ioanninon [The health of Pamvotis: Research on the hygienic and environmental problems of the Lake of Ioannina]. Ioannina: Ioannina University, 1989.

- Kolettas, Stefanos Ch. 2000. Oi Limnes ton Ioanninon kai tis Lapsistas [The lakes of Ioannina and Lapsista]. Ioannina: Publications of the Prefectural Authority of Ionannia, 2000.

- Natsis, Lazaros S. Pamvotis: I Limni ton Ioanninon [Pamvotis: The Lake of Ioannina]. Athens: OIKO Publications, 1992.

- Pappas, Stefanos D. Pamvotis: I Xiliotragoudismeni Limni ton Ioanninon [Pamvotis: The thousand-sung Lake of Ioannina]. Ioannina: Prefectural Authority of Ioannina, 2001.