In recent decades, disasters have impacted the western Indian Ocean region. Since 2018, multiple cyclones have devastated Mozambique and fluctuations in moisture have spurred a major locust outbreak in areas bordering the Arabian Sea. These disasters act on previously degraded environments and societies strained by population growth, poverty, political contests, and new practices and beliefs linked to globalization. Societies come to terms with disasters in these settings in ways meaningful to them. In other words, disasters can be both physical events and cultural experiences. For some residents in Tanzania and Mauritius, this includes sightings of nature spirits or mythological beasts: elsewhere called “cryptids.” References to serpents or a werewolf expresses the trauma of disaster, but also makes shared anxiety relatable and motivates societal debate about immediate experience in anticipation of the future.

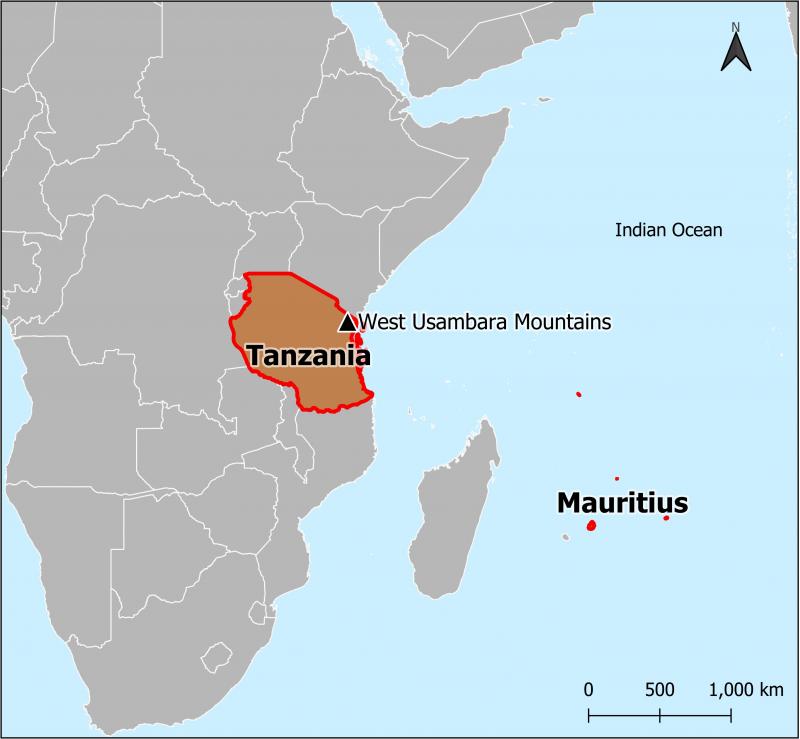

Map of the Western Indian Ocean with the West Usambara Mountains (Tanzania) and Mauritius marked.

Map of the Western Indian Ocean with the West Usambara Mountains (Tanzania) and Mauritius marked.

© Rory A. Walshe.

Courtesy of GQIS.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In northeast Tanzania, the West Usambara Mountains rise to 2,250 meters and shelter a biodiversity hotspot. These elevated “islands” were heavily forested in the past. According to oral traditions, the Shambaa—agriculturalists who speak a Bantu language—founded a highland kingdom at Vuga during the seventeenth century. The Shambaa continue to yield produce from rich soils along slopes that are relatively malaria-free. The Shambaa interact with the Zigua, who occupy the lowlands and negotiate a much drier and less healthy landscape. Interviewees identify mountaintops and other unique features as sacred domains of nature spirits: giant serpents, called nondo. In part, the Shambaa identify these nature spirits by the trails they inscribe along mountain gradients during heavy rains. Other residents affiliate the trails with the paths of mudslides and floods first said to have impacted the area more than a century ago.

West Usambara Mountains in Northeast Tanzania, approximately 75 kilometers inland of the Indian Ocean.

West Usambara Mountains in Northeast Tanzania, approximately 75 kilometers inland of the Indian Ocean.

© Jonathan R. Walz. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Orographic rainfall in the West Usambara Mountains derives from moisture in the western Indian Ocean. Forest clearance by residents has a long history in the highlands. However, by the late nineteenth century, German and, later, British colonials contributed to overharvests, which further destabilized slopes and reduced the quality of upper soil horizons important for farming. Soil degradation negatively influenced Shambaa livelihoods. According to Shambaa and Zigua interviewees, serpents began to emerge from “watery spaces” (lakes or bogs) atop mountains during triggering events, typically at the start of the long rainy season (in April or May). These impacts were layered over pre-existing eco-social changes and “harms,” including insufficient care for the land and cultural traditions. Serpent trails led to calls by some residents to return to the veneration of nature spirits. Public healing rituals performed after disasters reference serpents both to heal the land and to restore social order.

Serpent symbolism appears in everyday material culture in and around the West Usambara Mountains. For instance, potters make special vessels with applique “snake” designs. Such decorations parallel the level of liquid to be contained within vessels, just as mythological serpents are said to inhabit “watery spaces” and to create flood trails left on terrestrial surfaces.

Serpent symbolism appears in everyday material culture in and around the West Usambara Mountains. For instance, potters make special vessels with applique “snake” designs. Such decorations parallel the level of liquid to be contained within vessels, just as mythological serpents are said to inhabit “watery spaces” and to create flood trails left on terrestrial surfaces.

© Jonathan R. Walz. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Located two thousand kilometers from mainland Africa, Mauritius Island has a layered colonial history, including Dutch occupation (1598–1710), French rule (1715–1810), and the British colonial period (1810–1968). Throughout these periods, Europeans facilitated the transit and exploitation of a large number of enslaved Africans and indentured laborers from India. As a result, Mauritius Island currently has a diverse ethnic and racial make-up. During recent decades, several tropical cyclones have devastated the island. In 1994, cyclone Hollanda triggered “mass hysteria.” The cyclone caused a power blackout in some areas for more than one month. Trauma from the disaster and prolonged darkness convinced many Mauritians that a werewolf—or loup-garou—was on the island terrorizing residents, particularly women. In its human form, the werewolf was portrayed as a naked, oily man (and therefore difficult to capture). The Creole name for this particular episode—touni minuit—translates as “naked midnight.” Interviewees across the island explained that, after assaulting women, the creature would shapeshift into a large black dog and disappear into the night. Reported sightings convinced some Mauritians the werewolf preyed on anyone who was outside after sundown.

It has been speculated that pranksters and copycats, enabled by pre-existing folklore about the werewolf, sparked the “hysteria” after cyclone Hollanda. The loup-garou is part of Creole folklore documented as early as 1888. However, the werewolf may have earlier origins rooted either in narratives about Malagasy magic (from Madagascar) or in ancient totems known from southwest Asia. At its height, the commotion about the werewolf on the island encompassed large areas. Eventually, the president of Mauritius was forced to “intervene in the psychosis” through media to settle the commotion. Elites, in particular, portrayed conversations about the loup-garou as an isolated and embarrassing incident: a cultural response best forgotten.

In Mauritius, the werewolf is embedded in popular culture, such as this graffiti from Port-Louis.

In Mauritius, the werewolf is embedded in popular culture, such as this graffiti from Port-Louis.

© Rory A. Walshe. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Serpents in Tanzania and the werewolf in Mauritius are nature spirits and a mythological beast, respectively. For some residents, cryptids help to materialize anxiety in degraded or culturally contested settings, where disasters magnify change. Cryptids can motivate societal debate about change (and about potential resolution) in anticipation of the future. It is not coincidental that the cryptids in these cases take the form of serpents and a werewolf, each of which bundles oppositional categories. Serpents coil while at rest, a cyclical form seemingly without end. And, by shedding their skins, serpents link birth and death, as they are repeatedly “reborn.” In the second exemplar, the werewolf shapeshifts between human and animal (and back again), a change that occurs at the day-night boundary. The werewolf bundles forms but also represents a bond across time. These cryptids interlace opposites. By doing so, metonymy transposes each element onto the other, resulting in an imagination that change is fundamental and stability possible. It is only by accounting for cultural expressions, such as cryptids in the Indian Ocean region, that disaster responses can be better understood.

How to cite

Walz, Jonathan R. and Rory A. Walshe. “Cryptids and Disasters: Serpents and a Werewolf in the Western Indian Ocean Region.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2022), no. 5. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9398.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Jonathan R. Walz and Rory A. Walshe

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Conte, Christopher. “Forest History in East Africa’s Eastern Arc Mountains: Biological Science and the Uses of History.” BioScience 60, no. 4 (2010): 309–13. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2010.60.4.9.

- Degroot, Dagomar, Kevin Anchukaitis, Martin Baunch, Jakob Burnham, Fred Carnegy, Jianxin Cui, Kathryn de Luna, Piotr Guzowski, George Hambrecht, Heli Huhtamaa, Adam Izdebski, Katrin Kleemann, Emma Moesswilde, Naresh Neupane, Timothy Newfield, Qing Pei, Elena Xoplaki, and Natale Zappia. “Towards a Rigorous Understanding of Societal Responses to Climate Change.” Nature 591 (2021): 539–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03190-2.

- Feierman, Steven. Peasant Intellectuals: Anthropology and History in Tanzania. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

- Larson, Lorne. “Iconic Beasts, Imperial Museums, Global Showmen and Changing Sensibilities.” In Arts, Politics and Social Movements: In the Fields and in the Streets, edited by Elen Riot, Claudia Schnugg, and Elena Raviola, 211–54. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019.

- Nunn, Patrick. “Lashed by Sharks, Pelted by Demons, Drowned for Apostasy: The Value of Myths that Explain Geohazards in the Asia-Pacific Region.” Asian Geographer 31, no. 1 (2014): 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10225706.2013.870080.

- Rouphail, Robert. “Disaster in a ‘Plural Society’: Cyclones, Decolonization, and Modern Afro-Mauritian Identity.” Journal of African History 62, no. 1 (2021): 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853721000189.

- Walsh, Martin, and Helle Goldman. “Cryptids and Credulity: The Zanzibar Leopard and other Imaginary Beings.” In Anthropology and Cryptozoology: Exploring Encounters with Mysterious Creatures, edited by Samantha Hurn, 54–90. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.