When 363 members of the Bishnoi community sacrificed their lives to protect Khejri trees (Prosopis cineraria) in 1730, they likely organized India’s first environmental movement. The Bishnoi is a religious community centered primarily in the Great Indian Desert or Thar Desert with a centuries-long legacy of practicing environmental conservation, wildlife protection, and sustainable resource management. It traces its roots of ecological consciousness and environmentalism back to the teachings of its fifteenth-century guru, Maharaja Jambheshwar, popularly known as Jambhoji.

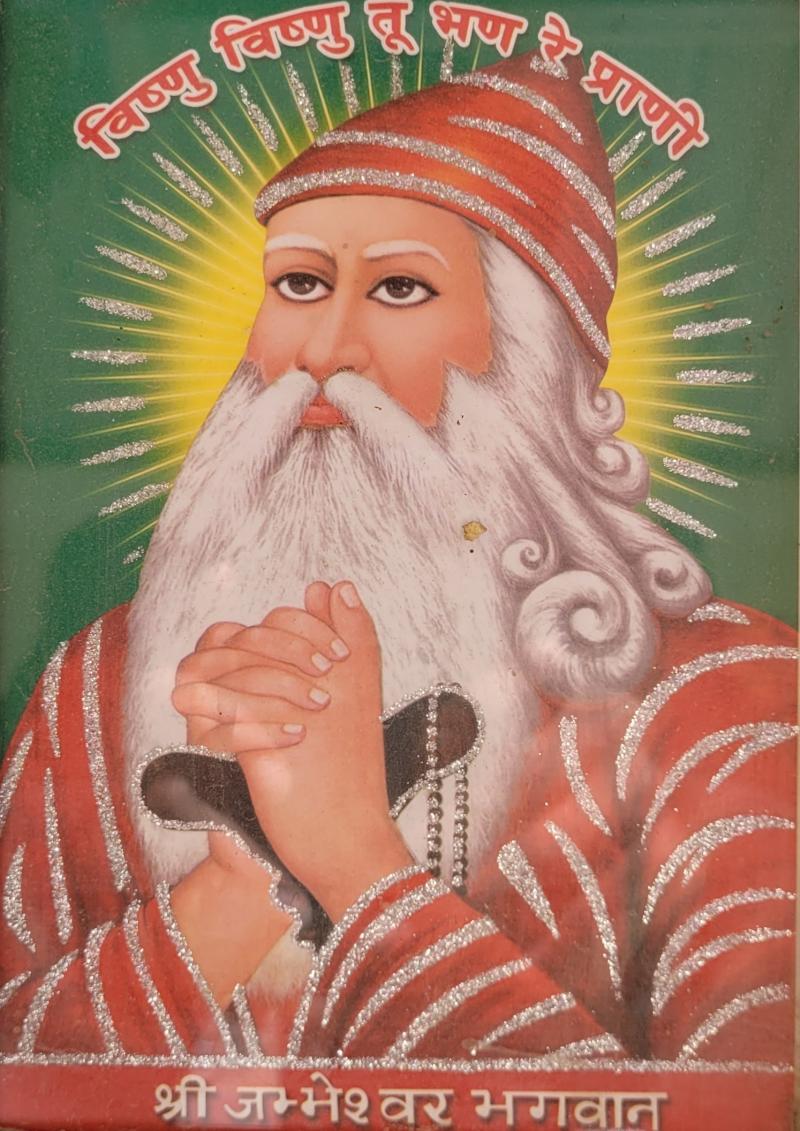

According to legend, in 1485, Saint Guru Maharaja Jambheshwar founded the Bishnoi sect of Hinduism in Marwar region of Rajasthan, India. Although the Bishnoi are today recognized as a subsect of Hinduism, they were recorded as Muslims until the 1891 Census of Marwar. While some scholars classify the Bishnoi as a liminal community because they practice both Hindu and Muslim rites, others consider them to be neither Hindu nor Muslim. The name “Bishnoi” derives from Hindi language, in which “Bish” translates to twenty and “Noi” translates to nine; it alludes to the original 29 edicts of Guru Jambhoji, which decreed how to live harmoniously with nature in the harsh climatic conditions of the Thar Desert. Notable among these edicts were the following: “do not cut green trees” and “be compassionate toward all living beings.” Jambhoji’s teachings specifically emphasized the protection of nature and wildlife because, as legend holds, earlier in his life, he had experienced severe droughts with tragic consequences for humans and animals alike. His logic was that if trees were protected, then the animals and people who depended on them would be protected in turn.

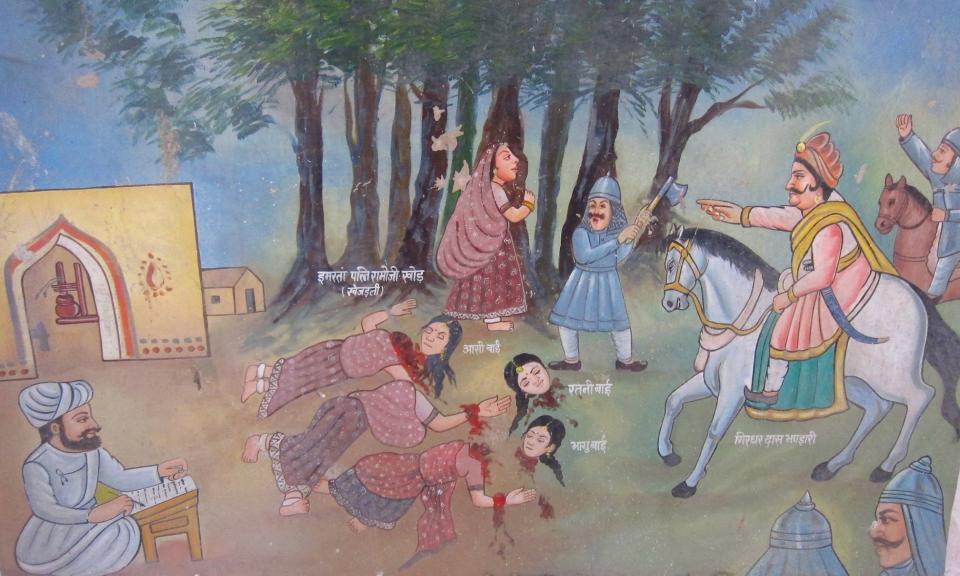

Photo of the Khejarli massacre, 1730, as displayed in the temple in Kherjarli.

Photo of the Khejarli massacre, 1730, as displayed in the temple in Kherjarli.

Accessed via Flickr. Click here to view source. This images has been cropped.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

Followers adhered to these principles even in times of crisis. In 1730, when Maharaja Abhay Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur, needed timber to construct the new royal palace, he sent soldiers to the Bishnoi village of Khejarli with orders to fell numerous Khejri trees—which have been sacred in Bishnoi culture. On 11 September 1730, Giridhar Bandhari, a representative of Maharaja Abhay Singh, arrived in Khejarli to fell the trees. When Amrita Devi Bishnoi, a resident of the village, was alerted to the threat, she and her daughters attempted to prevent the soldiers from cutting down the trees by hugging them while proclaiming:

सर सटे रुख रहे तो भी सस्तो जान

If a tree is saved even at the cost of one’s head, it is worth it.

In an effort to prevent their own trees from being cut down, the nearby Bishnoi villagers followed Amrita Devi’s example and embraced the Khejri trees in the area. The soldiers ignored the residents’ pleas, and 363 Bishnoi were killed, including Amrita Devi and her daughters. When the Maharaja learned of the massacre, he immediately ordered the woodcutting operation to be halted and apologized for the deaths. He also granted complete state protection to the Bishnoi villages of the region—this is no longer applicable today, but the nonhuman nature in the area is now protected by various legislations of the Indian government. In addition, the king issued a royal decree on a copper plate, prohibiting cutting trees and hunting animals within and around all Bishnoi villages. To honor the legacy of the Bishnoi’s sacrifice, the government of India established the Amrita Devi Wildlife Protection Award (ADWPA) in 2000, and 11 September was designated National Forest Martyrs Day in 2013.

Today, the Bishnoi community faces multiple environmental pressures: deforestation and biodiversity loss, depleting groundwater levels, aggressive mining activities, illegal poaching, and developmental land-grabbing. Despite these challenging conditions, the Bishnoi successfully manage their own forest in the Thar and work to maintain wild-animal populations through the use of traditional ecological knowledge and customary laws based on their religious beliefs. In line with Jambhoji’s teachings, the Bishnoi seek only to extract resources from nature as needed, as we found in a 2022–2023 primary ethnographic field survey among members of the Bishnoi community and nongovernmental organizations in Khejarli, Jajiwal, and Gharab of Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Specifically, they collect the leaves and pods of Khejri trees for vegetable and traditional medicinal uses. Besides, leaves are used as fodder for domestic animals such as goats, sheep, and camels. The Bishnoi people run community-based animal care centers to nurse injured, sick, and weak animals. Sometimes, Bishnoi women breastfeed injured fawn. Additionally, they practice community-driven monitoring systems to regulate deforestation activities and plant Khejri trees as a measure to safeguard against desertification. Further, they preserve community-managed sacred groves to protect sacred trees, sacred animals, and water; the rich biodiversity of these groves provides water in times of crisis. The harmonious relationship between the wildlife and people is visible in every Bishnoi village, with many wild animals (blackbucks, Indian gazelles, chinkaras, peacocks, great Indian bustards, partridges) freely roaming the area. The primary field survey also revealed that Bishnoi villages have significantly higher natural vegetation cover and wildlife population compared to parts of the Thar Desert, especially numbers of Khejri trees and blackbucks.

The Bishnoi might not be able to influence the dominant religious and environmental discourse beyond the Thar Desert, but their doctrine preaches the virtues of environmental conservation and wildlife protection and is being passed down within the community from the older to younger generations. The Bishnoi community’s religious value-based natural-resource-management strategy significantly contributes to sustainably managing natural resources in their region.

How to cite

Sohel, Amir, and Farhat Naz. “The Bishnoi: Revisiting Religious Environmentalism and Traditional Forest and Wildlife Management in the Thar Desert.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2024), no. 10. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9846.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2024 Amir Sohel and Farhat Naz

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Bikku. “Religion and Ecological Sustainability among the Bishnois of Western Rajasthan.” In Issues and Perspectives in Anthropology, edited by Rashmi Sinha, 45–68. New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2019.

- Chapple, Christopher Key. “Religious Environmentalism: Thomas Berry, the Bishnoi, and Satish Kumar.” Dialogue 50, no. 4 (2011): 336–43. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6385.2011.00634.x.

- Jain, Pankaj. “Bishnoi: An Eco-Theological ‘New Religious Movement’ in the Indian Desert.” Journal of Vaishnava Studies 19, no. 1 (2010): 1–20.

- Jain, Pankaj. Dharma and Ecology of Hindu Communities: Sustenance and Sustainability. London: Routledge, 2016. First published 2011 by Ashgate (Farnham). doi:10.4324/9781315576916.

- Mukhopadhyay, Durgadas. “Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Natural Resource Management in the Indian Desert.” In The Future of Drylands: International Scientific Conference on Desertification and Drylands Research, Tunis, Tunisia, 19–21 June 2006, edited by Cathy Lee and Thomas Schaaf, 161–70. Dordrecht: Springer, 2008. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6970-3_21.

- Natesh, S. “When Amrita Devi and 362 Bishnois Sacrificed Their Lives for the Khejri Tree.” Feminism in India. 11 September 2020. https://feminisminindia.com/2020/09/11/when-amrita-devi-and-362-bishnois-sacrificed-their-lives-for-the-khejri-tree/.

- Reichert, Alexis. “Sacred Trees, Sacred Deer, Sacred Duty to Protect: Exploring Relationships between Humans and Nonhumans in the Bishnoi Community.” MA diss., University of Ottawa, 2015. doi:10.20381/RUOR-4132-