During World War II, Australia experienced a shortage of agricultural workers combined with prolonged drought, which led to food shortages. In response, government campaigns encouraged Australians to grow victory gardens and raise chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus). Some 80 years later, as supply chains faltered during the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for backyard chickens once again soared in New South Wales (NSW).

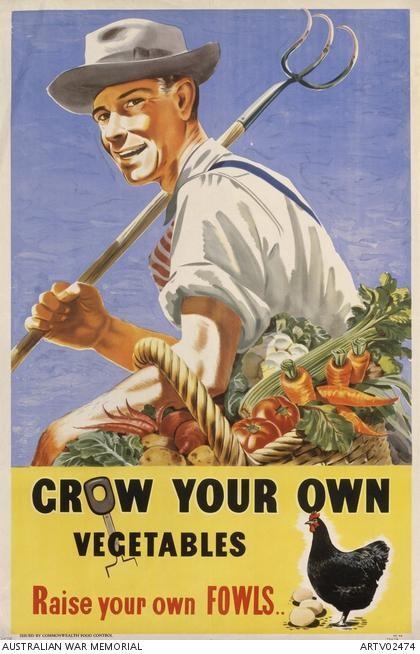

Wartime poster encouraging self-sufficiency by the Commonwealth Food Control, 1944.

Wartime poster encouraging self-sufficiency by the Commonwealth Food Control, 1944.

Unknown creator, 1944. Accession number ARTV02474. Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial. Click here to view the source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

However, council regulations have increasingly restricted the keeping of backyard chooks, as they’re affectionately known in the vernacular. Along with limiting the numbers of fowl that can be kept, urban councils prevent natural reproduction through forbidding the keeping of roosters, whose crowing they deem noise pollution.

This hasn’t stopped Ernest, a 70-year-old heritage Araucana enthusiast from NSW’s Central Coast, who I came to know during three years of ethnographic research into heritage-breed livestock and poultry rearing. “I do keep a rooster,” he told me conspiratorially over the phone in 2020, “he sleeps in an underground bunker of a night.” Ernest had buried a doghouse into which he sent his rooster at dusk, before releasing him the following morning around 9 a.m.

“Now, I’m being sexist,” he continued, “but the girls are much happier with a boy around. He will sort out any squabbles . . . So, I’ve found, excuse the expression, sunshine and sex produces a better egg.”

Ernest much prefers his own eggs to the supermarket’s. Like many Australians of his generation, he grew up with various breeds of backyard chooks. Eggs were the focus and, to preserve the “golden goose,” his family only consumed old hens and excess cockerels as special-occasion foods.

Over the past eight thousand years of domestication, from the jungle fowl’s origins in Southeast Asia, 1,600 distinct breeds of chicken have resulted from natural and artificial selection. Yet, since the middle of the twentieth century, when chicken rearing shifted from the farm to the factory, a handful of trademarked crossbreeds have come to dominate global markets, heavily selected for either egg production (layers) or meat production (broilers).

Among broilers, dizzying growth and feed conversion rates are embodied in Ross and Cobb chickens, from whom most commercial chicken meat in Australia derives. Meanwhile, hyperprolific Isa Brown, Hisex, and Hy-Line layers produce around three hundred eggs annually. Commercial layers are deemed spent at 18 months, while broilers are slaughtered at four to six weeks. Heritage chickens, while less profitable, can live beyond a decade.

The industrial model constructs these socially, cognitively, and emotionally complex creatures as dispensable commodities. By contrast, when chickens were first brought to Europe in the first millennium BCE, archaeological evidence suggests they were kept as valuable exotica for around 700 years before being utilized as a food source. Fanciers have continued to foreground chickens’ ornamental qualities and, since 1858, poultry clubs in NSW have hosted popular shows and breed displays.

As well as appreciating the birds’ ornamental value, Australians have repeatedly turned to backyard chooks for food security. So valued were eggs, that British colonists brought chickens to Botany Bay on the First Fleet to feed settlers. Indeed, livestock soon became integral to advancing the colonial frontier and to Indigenous dispossession. Today, 76 percent of Indigenous Australians consume livestock and poultry products, but this history demonstrates the ambivalence of livestock vis-à-vis food security for First Peoples.

Among non-Indigenous Australians, echoes of wartime efforts to bolster self-sufficiency via poultry rearing have reemerged during economic downturns, including in the rush to purchase hens during the 2008 global financial crisis.

Several species and breeds of poultry on Deborah Hurley’s family farm, “Dannybrooke,” Darling Downs, Queensland, c. 1894. Photo from the Hurley Family History Booklet, supplied by Gail Maree Costigan-White.

Several species and breeds of poultry on Deborah Hurley’s family farm, “Dannybrooke,” Darling Downs, Queensland, c. 1894. Photo from the Hurley Family History Booklet, supplied by Gail Maree Costigan-White.

© Gail Maree Costigan-White. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In 2020, as supermarket shelves emptied during the COVID-19 pandemic, again there was a rush on backyard chickens. Animated discussions unfolded in the poultry community: concerns abounded about chicken welfare in the hands of inexperienced keepers, as did jokes about everyone’s favorite neighbor suddenly being the “crazy chicken lady”—women historically being responsible for domestic chicken rearing, with many coming to love their chooks as quirky pets. Some hoped renewed respect for poultry might lead to more leniency in council regulations. Others worried that when eggs returned to supermarket shelves, or chickens stopped laying while molting, the birds would be dumped.

For Ernest, his chickens not only kept him fed but, given that he lived alone, were his main companions during NSW’s lockdowns. He reflected on parallels with the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–19, when his grandmother, a nurse, kept chickens to feed the family.

Ernest was particularly pleased to see renewed interest in heritage breeds. He worries about the homogenization of genetics in commercial layers and broilers, and the potential for new avian viruses to eradicate Australia’s preferred protein source. He sees the genetic diversity embodied in heritage breeds as a safeguard of galline longevity and the nation’s food security. Research demonstrating that susceptibility to Newcastle disease, as one example, varies considerably between chicken breeds supports Ernest’s views.

The pursuit of self-sufficiency, stemming from a fear of food insecurity, motivates many backyard chook keepers. One described how his now-deceased grandfather’s drive for chicken rearing was connected to his experiences as a refugee during World War II:

It was always about being self-sufficient, not relying on the government. Because he’d lost everything, his entire family in World War II. He’d been faced with the Nazis, and he’d come out [to Australia] with that mindset that I need to supply my needs, and my family’s.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, NSW was still reeling from the Black Summer bushfires, the worst on record, which had followed the devastating 2017–2020 drought. With the ecological and economic upheaval resulting from anthropogenic climate change, history suggests that desire for self-sufficiency will continue to grow. To this end, backyard-poultry keeping provides not only companionship and an economical and nutritious protein source, but also a sense of existential security in uncertain times.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Project scheme (project number DE200100595).

How to cite

Gressier, Catie. “The Backyard Chook: Australia’s Enduring Nest Egg.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2023), no. 11. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9621.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2023 Catie Gressier

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Beldo, Les. “Metabolic Labor: Broiler Chickens and the Exploitation of Vitality.” Environmental Humanities 9, no. 1 (2017): 108–28.

- Best, Julia, Sean Doherty, Ian Armit, Zlatozar Boev, Lindsey Büster, Barry Cunliffe, Alison Foster et al. “Redefining the Timing and Circumstances of the Chicken’s Introduction to Europe and North-West Africa.” Antiquity 98, no. 388 (2022): 868–82.

- Dixon, Jane. The Changing Chicken: Chooks, Cooks and Culinary Adventures. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2002.

- Marino, Lori. “Thinking Chickens: A Review of Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior in the Domestic Chicken.” Animal Cognition 20 (2017): 127–47.

- Muir, Cameron. The Broken Promise of Agricultural Progress: An Environmental History. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

- Oliver, Catherine. “The Opposite of Extinction.” Environment and History 28, no. 2 (2022): 197–202.

- Schilling, Megan A., Sahar Memari, Meredith Cavanaugh, Robab Katani, Melissa S. Deist, Jessica Radzio-Basu, Susan J. Lamont, Joram J. Buza, and Vivek Kapur. “Conserved, Breed-Dependent, and Subline-Dependent Innate Immune Responses of Fayoumi and Leghorn Chicken Embryos to Newcastle Disease Virus Infection.” Scientific Reports 9, 7209 (2019): 1–9.