In early summer, thousands of tourists flock to the western Swedish town of Trollhättan. Some of them might come for the party, for music and food, but the heart of the event is something else: over loudspeakers, an employee of the State power company Vattenfall announces to an eagerly waiting crowd: “In a few minutes the dam gates will open and 300,000 liters of water per second will pour into the old Göta River.” It is Fallens dag, the “Day of the Waterfall,” the yearly spectacle when the once-famous waterfalls of Trollhättan come to live again for a few hours.

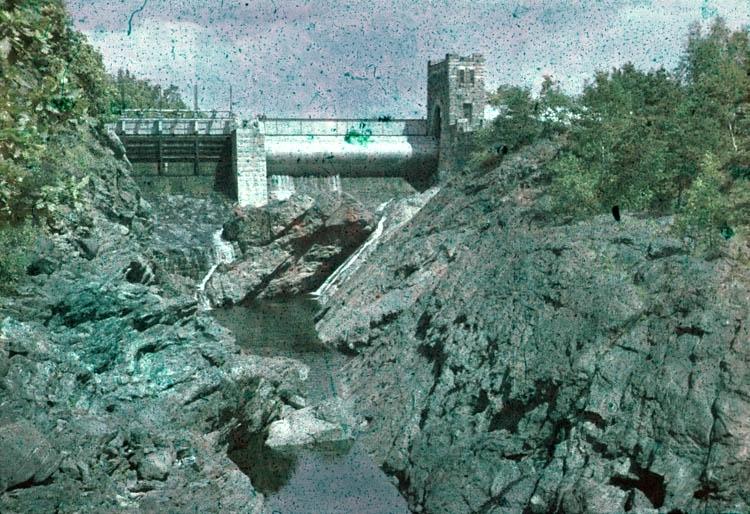

Acclaimed for their beauty, the waterfalls at Trollhättan had been a travel destination for centuries, when, in the late nineteenth century, a group of engineers, entrepreneurs, and statesmen began to plan what would be one of the world’s largest hydropower plants of the time. This first power plant went online in 1910 and by the end of the 1930s the water system of the lower Göta Älv had been restructured in such a way that only on occasional Sundays, when electricity demand was lower, a modest amount of water would flow in the old river bed. For the rest of the year, the Trollhättan waterfall remained dry.

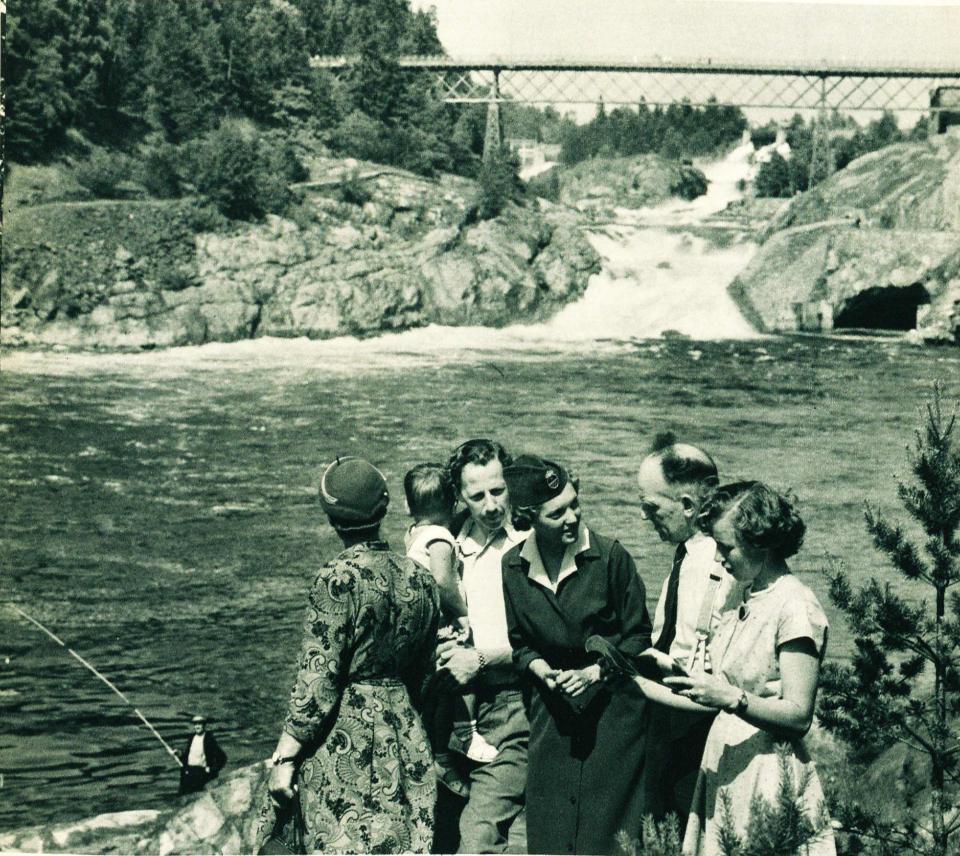

A power plant hostess presents the Trollhättan waterfalls to tourists.

A power plant hostess presents the Trollhättan waterfalls to tourists.

Accessed via Lennart Nilsson and Charlie Cederholm: Strömkarl. En krönika om vattenfall, dess miljöer och människor jubileumsåret 1959. Fritzes hovbokh: Stockholm, 1959.

© Lennart Nilsson

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

A new “tradition” started on 15 June 1959, according to Vattenfall’s own press communications. Through advertisements in newspapers and even in international radio shows tourists were invited to come to Trollhättan on that day. And they came. “40,000 people in 10,000 cars wanted to see the filled Trollhättan waterfalls,” was the headline in the national newspaper Svenska Dagbladet. The rush of cars caused serious congestion in Trollhättan, which had only 30,000 inhabitants at the time. “About 400 cubic [meters per second] were spilled in three two-hour slots and each time several thousand people barged on Oscar’s Bridge.” Maybe Svenska Dagbladet’s journalist chose an appropriate metaphor after all when he described the event as a “violent invasion.” When the event was repeated the following year with equal success, the military connotations were quite explicit: the spectacle of the waterfall was augmented by a showcase of local industry; among them a formation flight of the Swedish air force’s newly acquired SAAB airfighters.

The empty bed of Trollhättan waterfall, 1940s to 1960s.

The empty bed of Trollhättan waterfall, 1940s to 1960s.

Courtesy of Bohusläns museum.

© Bo Steinknecht, 2014

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In a sense it was the Göta Älv itself that prompted the start of this new “tradition.” Since early spring 1959, the river carried more water than usual and Vattenfall had to let this excess water run through the old river bed to avoid submersions upstream. This natural occasion coincided nicely with an increased interest in tourist events, both from the public as well as from the city of Trollhättan and its industrial corporations, like Vattenfall. It was the local tourist association headed by Gösta Vogel-Rödin that first pushed for rendering the flowing water at Trollhättan into a publicity event for the city. The Day of the Waterfall with its spectacular blending of natural beauty and technological prowess embodied a palpable origin story both for the waterfall landscape, the city of Trollhättan, and the whole Swedish nation. Local industries presented their displays in a progress narrative, contrasting their first prototypes with models of their latest constructions, while the narrator of a short film produced by Vattenfall in 1959 cast the transformation of Trollhättan’s waterfall landscape as a coming-of-age story that resonated well with national narratives of Sweden’s maturity as a modern welfare state.

“The falls are gone. But every now and then the river is let loose again so that she can show what a savage she was in her youth. The playful rapids have become calm and serious canals … where [the] power station stands as a monument to the pioneers, who started the age of Vattenfall in Swedish power history.”

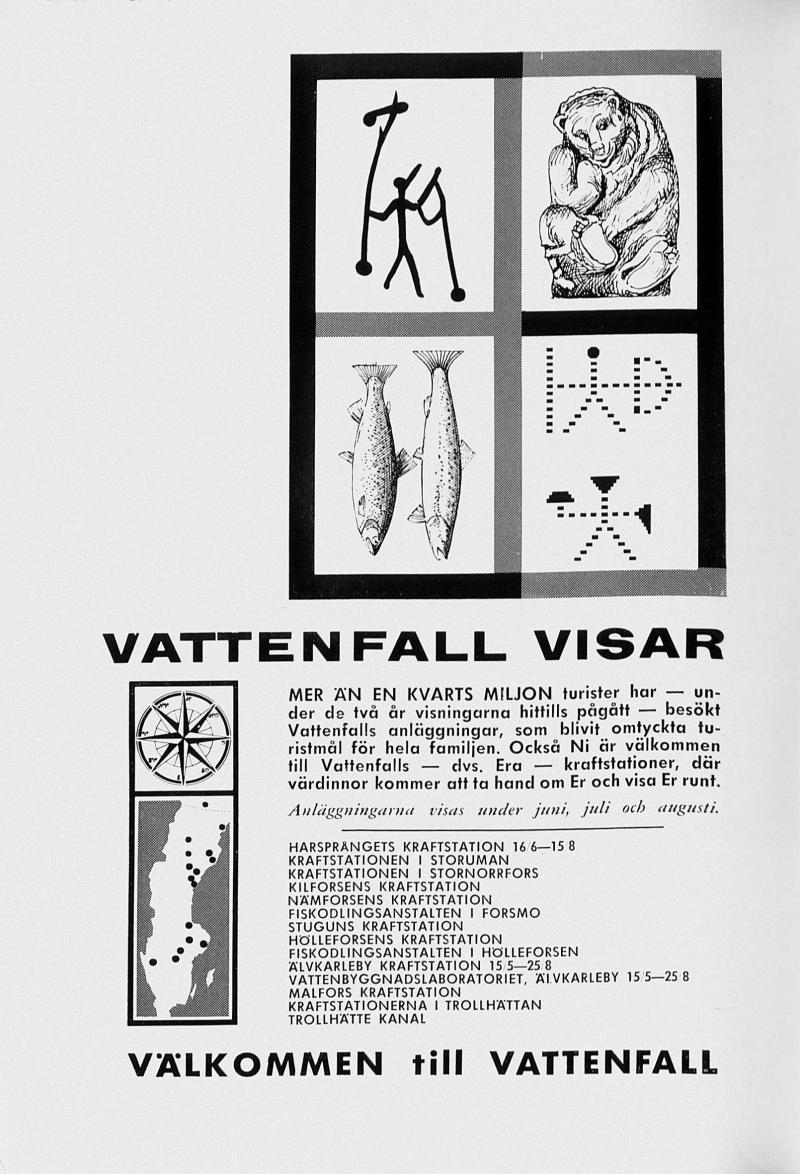

“Vattenfall presents”: Advertisement for guided tours around the Swedish State power plants.

“Vattenfall presents”: Advertisement for guided tours around the Swedish State power plants.

Accessed via Sveriges Natur. Svenska naturskyddsföreningens tidskrift 3, no. 50 (1959).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

For Vattenfall, especially, the Day of the Waterfall connected seamlessly to existing efforts to showcase their power plants as tourist sites. Faced with increasing protests from a civil society taking issue with the encroachments on landscapes and livelihoods brought about by the rapid expansion of hydropower schemes, Vattenfall set up a nation-wide PR strategy in the mid-1950s to foster good-will for the company. Brochures and guided tours, but also films produced by the company all went under the label “Vattenfall presents” (Vattenfall visar) and gave the company an appealing visual identity. Since 1956, Vattenfall had professionalized their tourist activities by employing young women as “waterfall hostesses.” Equipped with stylish uniforms, glossy brochures, and polished smiles, they replaced the plant’s all-male technical and operational staff that had taken care of tourists so far. In this context, the gendered imagery of the above film quote is no coincidence. In a variant of the commonplace association of women with nature, the beauty of the “waterfall hostesses” was repeatedly praised in conjunction with the beauty of the waterfall. Yet, the hostesses also meant a departure from such conventional narratives, which represented nature as female and a “savage” force to be mastered by male engineers. Visitors to Vattenfall’s power plants were no longer supposed to experience hydropower as purely “male” and “rational” technology. Rather, the association of the hostesses’ friendliness and the beauty of the wild waterfall with the male domain of power production was a means to give Vattenfall an environmentally- and socially-friendly image.

Det hände 1956—Vattenfall [This happened in 1956—Vattenfall]. Beginning at 15:29, a power plant hostess presents Nämforsen power plant to a crowd of curious tourists in a company newsreel from 1956. Film by Ivan Christoferson, Nils Jerring, Arne Lagercrantz, Svensk Filmindustri, 1956. Public domain, accessed via YouTube.

How to cite

Zimmer, Fabian. “The Day of the Waterfall: Tourism, Identity, and Gender at the Trollhättan Hydropower Plant.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2021), no. 33. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9372.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Zimmer, Fabian

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Jakobsson, Eva. “The History of Flowing Water Policy in Sweden: From Natural Flow to Industrialized Rivers.” In Rivers and Society: From Early Civilizations to Modern Times (A History of Water 2/2), edited by Terje Tvedt and Richard Coopey, 424–39. London / New York: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

- Jakobsson, Eva. “Industrialized Rivers: The Development of Swedish Hydropower.” In Nordic Energy Systems: Historical Perspectives and Current Issues, edited by Arne Kaijser and Marika Hedin, 55–74. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1995.

- Macfarlane, Daniel. “The Niagara Telecolorimeter.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2018), no. 28. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8492

- Nye, David E. American Technological Sublime. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

- Rogers, Richard A., and Julie K. Schutten. “The Gender of Water and the Pleasure of Alienation: A Critical Analysis of Visiting Hoover Dam.” The Communication Review 7, no. 3 (2004): 259–83.

- Zimmer, Fabian. “Nature, Nation and the Dam. Narratives about the Harnessed Waterfall in Early Twentieth-Century Sweden.” International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity 7 (2019): 171–208.

- Zimmer, Fabian. Hydroelektrische Projektionen. Eine Emotionsgeschichte der Wasserkraft im Industriefilm. Göttingen: Wallstein, forthcoming.