The Power of Waste

Waste relates to power in three important ways: First, it aligns with many power structures of our world, whether they relate to race, class or gender, or exist between countries and world regions. Second, waste can be an empowering feature, as the chapter on living with waste illustrates. Third, waste in itself is also a powerful object. Waste is neither passively disposed of or discarded, nor easily transformed into a different state of being through up-cycling or down-cycling, reuse or recycling. Whether we produce, move or discard waste, it comes with side effects, sometimes even unanticipated consequences. We understand this power best when we think about how waste and waste pollution infiltrates our bodies, our genes, how it threatens our health and damages the environment we live in. Waste’s life is what constitutes its power.

“Rust-colored runoff from the abandoned quicksilver ghost town of New Idria, CA.” Photograph by Matthew Lee High, 2007.

“Rust-colored runoff from the abandoned quicksilver ghost town of New Idria, CA.” Photograph by Matthew Lee High, 2007.

Photograph by Matthew Lee High, 2007. https://www.flickr.com/photos/matthigh/2273483382/in/photolist-4sQ944-4s….

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

Today, many scholars treat waste as a matter of perspective. Yet, waste is also materiality—living or at least changing materiality. This materiality may be relatively harmless or it may be hazardous to our health and environment. It may be yesterday’s newspaper or the toxic byproduct of manufacturing, farming or hospitals. The material can be liquid, solid, sludge or gas and it can contain chemicals, heavy metals, radiation, pathogens or other toxins that—if handled poorly—pose a substantial threat to our health and environment, as well as that of future generations.

In many countries around the world, landfills are the largest source of human-generated methane—a powerful greenhouse gas—alongside carcinogens such as benzene or vinyl chloride. Leachate from these places often contains a toxic cocktail and despite elaborate precautionary measures including soil covers, synthetic liners, and leachate collection systems, landfills can easily contaminate groundwater or surface water in the area.

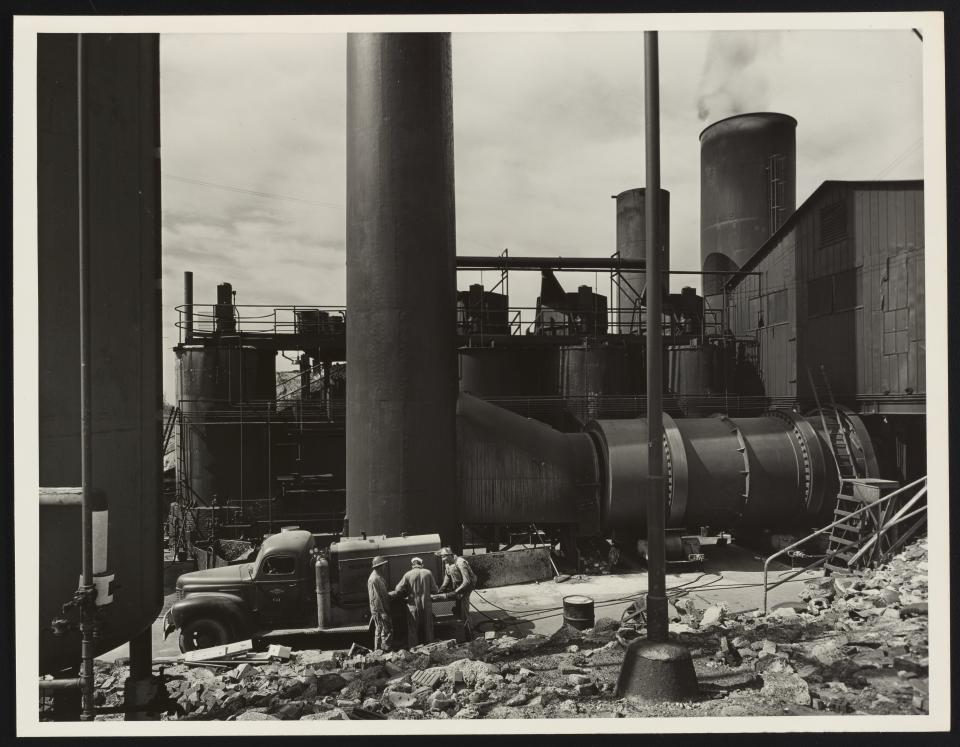

General view of a section of the waste disposal facilities at the Dow Chemical Company plant in Midland, Michigan, USA, 1952. Photograph from the Science History Institute’s Dow Chemical Company Historical Image Collection.

General view of a section of the waste disposal facilities at the Dow Chemical Company plant in Midland, Michigan, USA, 1952. Photograph from the Science History Institute’s Dow Chemical Company Historical Image Collection.

Photograph from the Dow Chemical Company Historical Image Collection, Box Oversized Plants 1, Science History Institute, Philadelphia. https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/cc08hg17w. No known copyright.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Waste incinerators do not provide a clean alternative. They transform trash into heat and ash and create an air pollution stream of harmful compounds that may contain carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, ammonia or nitrogen oxides. In the end, waste incinerators also produce waste, such as incinerator ash, which in turn needs to be disposed of. And even the latest hype in waste studies, a plastic eating bacterium, Ideonella sakaiensis, emits a significant amount of CO2.

Drawn by Nika Korniyenko , 2014.  This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artist Nika Korniyenko explores the surreal and unimaginable consequences of nuclear waste in this cartoon—showing how a waste leak may render a glowing deer, 2014.

Despite the legal distinction between hazardous and nonhazardous waste, there is no such thing as harmless waste. Municipal solid waste may not pose problems when disposed of in a leachate-proof landfill, but it does pose a problem when dumped in pristine wetlands. All waste streams need to be monitored, some over a very long period of time. Artist Nika Korniyenko engages with the remnants of atomic energy production. Through leakages, which could possibly continue up to one hundred years into the future, radioactive waste contaminates first the soil, then the plants, and then the animals feeding on them. Moving up the food chain, radioactivity eventually reaches the human body, which is “the last sink,” according to Kate Brown. Seldom acknowledged, human bodies are as much a repository, a dump of human-made waste products, as are rivers, groundwater, soils, plants, and animals. Explore the work of the Deadly Dreams research network to learn more about the history of these toxins.

Through its own power, its ability to harm humans and the environment they live in, waste gives power to others. It enforces existing demarcation lines between people, sexes, regions, and countries. How to deal with the toxicity and pollution aspect of waste has long created repeated and substantial controversies that tie in with fervent debates about environmental racism and justice. Think, for instance, about pollution disasters such as Love Canal, where an entire neighborhood in the United States was built upon a former (forgotten) waste dump that then resurfaced and made people sick. Another example is that of the mercury crises in the 1960s and early 1970s in Japan, Sweden, Canada, and the United States, where disposed mercury resurfaced through the aquatic food chain.

Often, it is the underprivileged who suffer the most. Waste is not an equalizer—it strengthens existing power relations, reinforcing social and global inequality.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of book and film profiles and articles showcased on the Environment & Society Portal. View the individual gallery items online or in the appendix of this PDF.

Brown examines health effects of radioactivity, little acknowledged by governments, who instead prefer to focus on “exposures” and isotope measurements in the environment. She focuses on Ozersk, the town with Russia’s first plutonium plant and how people are also a repository of manmade waste, just like rivers, ground water, soils, plants, and animals. (Adapted from author’s abstract)

Learn more

The paper focuses on the 1987 to 1988 dumping of hazardous industrial waste in Koko, Nigeria, especially on the cartoonists, that were in the public debate over the waste-dumping incident from the Nigerian tabloids in June 1988. The paper critically analyzes the number, content, and contexts of cartoons that covered the toxic-waste dumping. (Adapted from author’s abstract)

Learn more

Claro focuses on compensation for environmental risks as a necessary condition for local acceptance of waste treatment facilities. By focusing on the siting of a sanitary landfill in Santiago, Chile, this paper explores the performance of both monetary and in-kind compensations and relates the analysis to the notion of social norms of exchange. The absence of compensation is linked to fraternal relations based on care. (Adapted from The White Horse Press)

Learn more

The ALARM began in 1991 as a revolutionary ecological news quarterly published by Earth First! groups active in the northeastern United States, emphasizing news and direct actions significant to regional and indigenous groups. Massachusetts Earth First! published issue 11, which updates readers on the radioactive waste management proposal in Massachusetts. (Adapted from the Environment and Society Portal)

Learn more

Nations and corporations in the “global North” export toxic waste to developing countries, causing harm to ecosystems and those who live there. Pellow examines transnational environmental justice movements to challenge and reverse this issue. He argues that waste dumping from rich to poor communities is a form of transnational environmental inequality that reflects North/South divisions in a globalized world. (Adapted from The MIT Press)

Read more

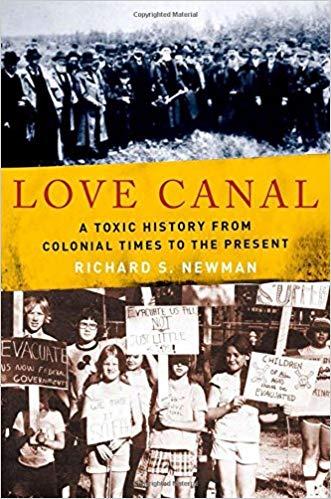

In 1978, citizens of Love Canal, NY, protested the leaking of toxic waste from a local site, advocating for environmental justice. The activists achieved the government relocation of their families and government/industry remediation of the dump itself. Love Canal remains a watchword of hazardous waste reform and one of the most significant environmental disasters in US history. (Adapted from Oxford University Press)

Learn more

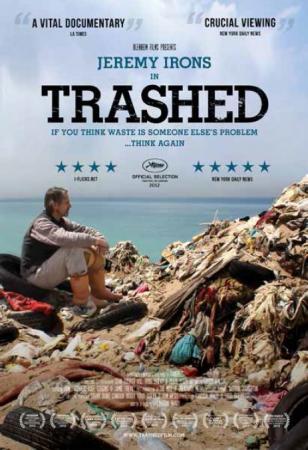

On a boat in the North Pacific, Jeremy Irons faces the reality of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and the effect of plastic waste on marine life. Global warming is melting ice caps and releasing decades of old poisons, which was stored in the ice, into the sea. The film examines solutions to the pressing environmental problems, some being as frightening and toxic as the problem itself. (Adapted from the Official Film Website)

Learn more

Experiences of exposure to toxicity and pollution, however, can also be an empowering resource for people. The guerrilla narrative project Toxic Bios collects stories from people all around the world who have decided to speak up. Listen to their stories of emancipation. Similarly, Ecuadorian communities in the Amazon region have taken the project of bioremediation into their own hands to clean up after almost five decades of oil exploration.

Los Afectados, the affected ones, have been living downstream of the oil production of the American company Texaco for half a century in the Oriente of Ecuador - their decades-long struggle for compensation and clean-up is ongoing. This image shows Donald Moncayo of Toxitours in front of one of the almost 800 oil pits left behind. Photograph by Maximilian Feichtner, 2018.

Los Afectados, the affected ones, have been living downstream of the oil production of the American company Texaco for half a century in the Oriente of Ecuador - their decades-long struggle for compensation and clean-up is ongoing. This image shows Donald Moncayo of Toxitours in front of one of the almost 800 oil pits left behind. Photograph by Maximilian Feichtner, 2018.

Photograph by Maximilian Feichtner, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Lastly, the movie Living Downstream captures Sandra Steingraber’s emancipatory struggle against pollution and big corporate industries. Pollution disasters exhibit how essential it is to take precautionary care, and how helpless we often remain when we no longer suspect that which we removed to be “out of sight.” Follow Sandra Steingraber’s fight against invisible toxins in our immediate environment as a result of unregulated, ill-regulated or illegal waste dumping.