Living with Waste

Waste is a fundamental indicator of life. As much as the acrid, black smoke emanating from industrial smokestacks in the nineteenth century indicated that business was good, the existence of garbage shows that life is present. Biologically speaking, it is only when we are dead that we stop producing waste. Even as we discover economically profitable reuses for waste objects, we continue to produce more—it seems that we cannot function without making at least some waste. Film director John Webster comically and drastically captures this in his documentary Recipes for Disaster, which follows his own little family on a year-long journey on an oil-free diet. Future archeologists may go through landfills to learn about today’s socialization and play “waste detective” as Christof Mauch writes in his introduction to the RCC Perspectives issue “ Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Politics and Culture of Waste.” Already today, artists, anthropologists and social workers visit waste sites to document life and human-waste interaction.

“Mohammed Camara, a waste recycler at Agbogbloshie, Ghana, the world’s largest e-waste dump, daily exposes his health to the toxic fumes from burning malfunctioning USB cords and other electronic materials to get to the copper inside.” Caption and photograph by Kevin McElvaney, 2013.

“Mohammed Camara, a waste recycler at Agbogbloshie, Ghana, the world’s largest e-waste dump, daily exposes his health to the toxic fumes from burning malfunctioning USB cords and other electronic materials to get to the copper inside.” Caption and photograph by Kevin McElvaney, 2013.

© 2013 Kevin McElvaney. http://kevin-mcelvaney.com/portfolio/agbogbloshie/.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Although landfills are usually located far from human sight, they are not devoid of human life, let alone non-human life. There are the landfill workers, whose job it is to keep the trash as compacted and orderly as possible. They use heavy equipment, such as bulldozers or tractors, to compact the garbage and distribute it evenly. They sometimes also spray the layers of garbage with water to keep dust from blowing around. Waste workers also greet us at the gate of a recycling facility, inspect the load for banned materials, such as chemicals and tires, and generally help us sort our trash. Then, there are the scavengers—those people who go through the trash at the waste dump to see if there are still valuables and recyclable objects to be found. They are the catadores and cartoneres of Brazil and Argentina, or the scavengers of e-waste at Agbogbloshie in Ghana who have found their own way to live with trash.

A family in Guatemala City survives by gathering hundreds of used plastic containers. They classify each of them and even separate them by size. Other families collect only cardboard or tin/aluminum cans and few collect all of them. Photograph by byroN José sun, 2013.

A family in Guatemala City survives by gathering hundreds of used plastic containers. They classify each of them and even separate them by size. Other families collect only cardboard or tin/aluminum cans and few collect all of them. Photograph by byroN José sun, 2013.

Photograph by byroN José sun, 2013. https://www.flickr.com/photos/byronjsun/11539932444/in/album-72157638996….

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

“Cardboard…” This man has collected cardboard to sell to a recycling center at Bacolod City, Philippines. Photograph by Brian Evans, 2018.

“Cardboard…” This man has collected cardboard to sell to a recycling center at Bacolod City, Philippines. Photograph by Brian Evans, 2018.

Photograph by Brian Evans, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

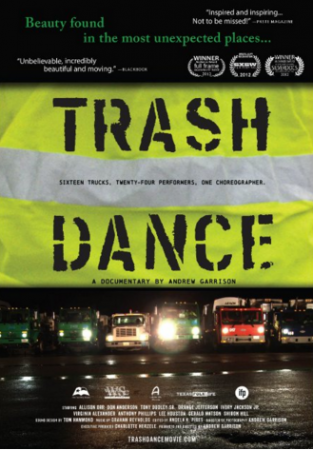

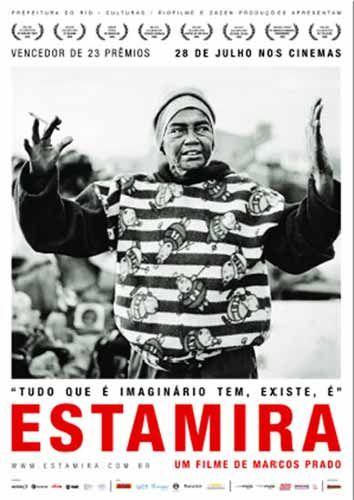

Engage with the filmic and artistic works of photographer Kevin McElvaney (Agbogbloshie), film directors Sean Walsh (Hauling), Andrew Garrison (Trash Dance), Marcos Prado (Estamira), Marco Pasquini (Maputo Dancing Dump) and Ernesto Livon-Grosman (Cartoneros), or artist Vik Muniz to learn more about “waste people.” The sources assembled in this chapter may give you a different understanding of those living and working at a landfill.

Living with waste poses many challenges. It can induce damage to the environment and pose health risks. At the e-waste dump at Agbogbloshie, Ghana, for instance, waste workers use their bare hands to recycle copper. Daily, they expose their health to the toxic fumes from burning malfunctioning USB cords and other electronic materials, to get to the copper inside. Similarly, Marcos Prado’s movie Estamira—about a 63-year old woman who suffers from schizophrenia and has for the past 20 years lived and worked at Brazil’s largest waste dump—may give you a sense of the harshness and strain that our bodies are subjected to because of waste.

Other sources in this collection, in turn, illustrate that living with waste can also exert a sense of belonging. Contrary to cultural theory distinguishing waste as the rejected that produces a sense of moral failure, some artistic documentations unearth a distinct sense of pride felt by those who live with waste. Take Vic Muniz’s movie Wasteland, for instance, which tells the stories of Suelem and Magna. Both women are waste pickers and express pride in their work. They provide for their families in a way that creates honor, not humiliation. They are cartadores—not prostitutes, or tricksters at the Copacabana, and not involved in drug trafficking. Similarly, Tiaõ, the young and charismatic president of ACAMJG (the Association of Recycling Pickers of Jardim Gramacho) feels the call to leadership through his relationship with waste. Inspired by the political texts he finds in the waste, he successfully fights to improve working conditions. These well-crafted examples strive to challenge a sort of institutional racism that sees waste workers at the bottom of the human food chain.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of book and film profiles and articles showcased on the Environment & Society Portal. View the individual gallery items online or in the appendix of this PDF.

Choreographer Allison Orr finds beauty and grace in garbage trucks, and in the unseen men and women who pick up our trash. Filmmaker Andrew Garrison follows Orr as she rides along with Austin sanitation workers on their daily routes to observe and later convince them to perform a most unlikely spectacle. On an abandoned airport runway, two dozen trash collectors and their trucks deliver—for one night only—a stunningly beautiful and moving performance, in front of an audience of thousands. (Source: Official Film Website)

Learn more

Claudines is father to over 27 children and many others, who make their living out of recycling material that others have thrown out. He is well known by locals, who often donate used goods, which he restores and sells. Claudines and his family serve as a symbol of the thousands of people in Brazil who resort to recycling in order to make a living and suffer prejudice and discrimination as a result. (Adapted from the Official Film Website)

Read more

On the outskirts of Maputo, the Hulene district is the city’s largest garbage dump, “lixeira.” This world of degradation and continuous struggle for survival is where groups of hip-hop dance were created. Music from African-American communities paired with agility and spontaneity turn any occasion into a show. In the midst of this microcosm, we uncover the deep vital strength of this place. (Adapted from The Cooperative Suttvuess)

Learn more

Cartoneros follows the paper recycling process in Buenos Aires from the trash pickers who collect paper, through middlemen in warehouses, to executives in large corporate mills. The film follows the trash from the neighborhood sidewalk to the paper mill and is both a record of an economic and social crisis and an invitation to audiences to rethink the value of trash. (Adapted from Documentary Educational Resources, Inc)

Learn more

Estamira tells the story of a 63-year-old woman who suffers from schizophrenia and lives and works at the waste disposal site of Jardim Gramacho in Rio de Janeiro. The film shows her life during four years of continuous medication; reveals her transformation and the effects the drugs had on her. With a poetic discourse, Estamira lives for the mission that was set upon her: to reveal and to reclaim the truth. (Adapted from Zazen Produções)

Learn more

Brazilian-born artist Vik Muniz has won international acclaim for his artwork made from recycled materials. But his work took on deeper resonance when he returned to Rio de Janerio and visited the pickers working Jardim Gramacho, the largest landfill in the world. A portrait on the power of art to make social change, this film is a reminder that we have means available to us to create change. (Adapted from Tales from Planet Earth)

Learn more

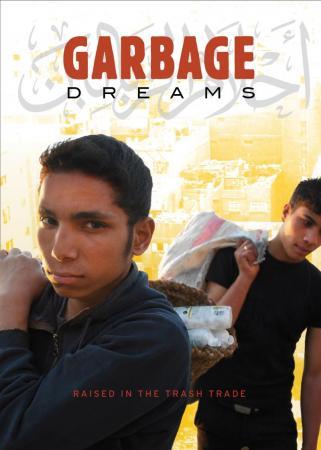

Garbage Dreams follows three teenage boys born into the trash trade and growing up in the world’s largest garbage village, on the outskirts of Cairo. It is home to 60,000 Zabaleen, Arabic for “garbage people.” Far ahead of any modern “Green” initiatives, the Zaballeen survive by recycling 80 percent of the garbage they collect. When their community is suddenly faced with the globalization of its trade, each of the teenage boys is forced to make choices that will impact his future and the survival of his community. (Source: Official Film Website)

Read more

Waste can also illustrate (trans)formative power on people. The movie Maputo Dancing Dump, for instance, uncovers the garbage dump as a creative space. Taking music and rhythm from African-American communities, young men at the dumpsite in Mozambique create hip-hop dance groups in the midst of collections of trash. Similarly, in Trash Dance, choreographer Allison Orr finds beauty and grace in the garbage trucks of Austin and, in a one-night spectacle, turns the unseen men and women who pick up the city’s trash into dancers. In these portrayals, the waste people are no longer at the end of the commodity chain, but are transformed by a deep, vital strength of the waste spaces they inhabit.

Finally, in his piece “Onions and Tires in Sodom and Gomorrah,” Oliver Schwab takes us back to the silences and subtleties that are part of the stories of these waste people, too.

With a high proportion of poor and socially disadvantaged residents, the e-waste dump Agbogbloshie has gained the nickname “Sodom and Gomorrah,” and is notorious for its high crime rate. Most people come from the rural areas of Ghana in search of a future in the urban agglomeration of Accra. Many are stuck in Agbogbloshie. In June 2015, hundreds of people died in Agbogbloshie as a result of a flood and fire in one of the neighborhoods. Many lost their homes. In response to this disaster on 3 June, the municipality cleared the neighborhood by sending a massive police presence equipped with armored vehicles and automatic weapons. Agbogbloshie is as much a social tragedy as it is an environmental one.