When in 1923, Mathias F. Chapman arrived in the Port of Los Angeles with 11 chinchillas, few expected that he would revolutionize the fur-trade business. Previous attempts to breed the little Andean mammal in captivity had failed, and traders and consumers feared that the days of the chinchilla coat, a garment that usually required 110 skins, would soon be over. But despite all odds, in 1946, Life magazine reported, there were near 200,000 chinchillas raised in captivity in the United States. Breeding had replaced hunting, and the chinchilla became a North American commodity.

Chinchilla pelts in the warehouse of the auction house Kopenhagen Fur.

Chinchilla pelts in the warehouse of the auction house Kopenhagen Fur.

Photo by Vadave, 2009. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

To understand this radical transformation, we need to go back to the Andes and Chapman’s crossing. Traveling through Chile in the 1830s, French naturalist Claudio Gay saw for the first time a chinchilla, one of the “most beautiful animals,” as he wrote in his natural history. The Chinchilla lanigera (Molina 1782) was the most sought and valued chinchilla. It originally lived in the Chilean valleys of Illapel and Choapa to the south of Peru and Bolivia, a territory known for its mining industry, arid landscape, and limited vegetation. Indigenous people, wrote José de Acosta in his Natural and Moral History of the Indies (1589), used animal hair to make blankets and coverings. Throughout the nineteenth century, hunting came in tandem with the expansion of the mining industry and the destruction of local habitats such as the algarrobilla, a shrub sought for its tannins that chinchillas also consumed. The docile mammal with a soft coat became a global commodity, complementing a collection of South American animals used for fur, including seals and guanacos. Between 1898 and 1910, Chile exported about seven million chinchilla pelts per year. Pushed by high prices and soaring demand, hunters used fire and dogs without discriminating between old and young or male and female animals. Hunting methods, lack of regulation, and rising demand in the North Atlantic created the perfect storm.

In 1919, Chapman got a job as a mining engineer in the copper town of Potrerillos, in the southern tip of the Atacama Desert. By then, the chinchilla was almost extinct. Magazines and newspapers tell a similar story of how he first encountered the animals and decided to capture them, transport them to the United States, and then open a farm. While working at the mine, Chapman bought a chinchilla from a trapper and spent the next three to four years looking for animals to raise. He worked closely with locals, and many times he joined them and traveled throughout the Andes to Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina. His experience was not unique. US engineers working in Latin America usually toured the surrounding areas. Hunting, exploration, and expeditions were part of their culture, their recreational activity, which informed the way they experienced what they saw as remote regions.

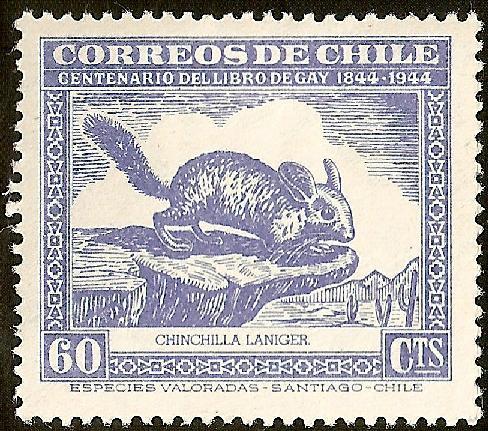

Commemorative series Claude Gay, depicting a Chinchilla lanigera Molina, 1948.

Commemorative series Claude Gay, depicting a Chinchilla lanigera Molina, 1948.

Photo by Penarc, 2009. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Previous efforts to raise chinchillas in captivity had failed. In the early 1920s, scientific knowledge about this animal was still scarce. It included a few references in natural history treatises, travelers’ accounts, and a detailed study by Edward Turner Bennett, a zoologist at the London Zoo. In 1901, Federico Albert, a German-Chilean naturalist, published a short and accessible survey of the animal and its behavior, calling attention to the devastating impact of unregulated hunting. Chapman may have had access to some of these books and articles, but more probably, he learned from trappers and locals and, most importantly, by observing the habits of the little animals. This method would become the basis of his and other breeders’ success.

Relocating chinchillas from their home environment to southern California was a grueling task. Chapman designed a special cage for the ocean trip between Chile and Los Angeles. As John Angus Haig wrote in the Nation’s Business magazine in 1937, Chapman “built an ingenious box with chinchilla pens in the ends and an ice compartment in the middle.” He slowly moved them to lower altitudes to guarantee acclimation, and after a year, they were ready to sail north. The trip from Iquique, Chile, to Los Angeles Harbor took about forty days and was incredibly challenging. Despite his constant care, one chinchilla died, and all lost their hair. Chapman’s first farm in Tehachapi, a small mountain town in the Sierras at 3,970 feet above sea level, was unsuitable for his business. Then, he moved the animals down to Inglewood, South Los Angeles.

The Chapman farm produced knowledge about domestication and acclimation, attracting visitors from Hollywood stars to animal experts. Many would come to replicate his route, method, and, especially, the icebox. In 1939, the LA Times reported that James F. Mitchell adapted the icebox to bring chinchillas from Peru to San Diego, California, where he and his wife opened a ranch. The chinchilla business thrived. In the early 1940s, Chapman’s son, Reginald, opened a new farm in Big Bear and a small factory specializing in cages, exercise wheels, and other products.

Mae Murray wearing a chinchilla coat.

Mae Murray wearing a chinchilla coat.

Bain News Service, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, ca. 1920. Accessed via Flickr.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The breeding business expanded in the 1930s–1940s, and farms popped up throughout the western United States and Canada. But while many advertised it as a lucrative activity that could supplement ranchers’ income, raising chinchillas was hard work. The animals were delicate and susceptible to high temperatures and diseases, the daily cleaning of the cages was time-consuming, and profit was unreliable. According to a booklet from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), ranchers kept the animals in metal, wood, or wired-floored pens in basements or other dark buildings. Space was always an issue, especially in ranches located in semi-urban areas such as the San Fernando Valley. While many admired their beauty and friendliness, they were a commodity and a business. Ranchers kept records, weighed them regularly, and tattooed an identification number in one of their ears. Most ranchers were breeders, but the largest ones also sold pelts. To kill a chinchilla without damaging the fur, they injected Nembutal or strychnine, a method considered less cruel than hunting with dogs as tappers used to do in the Andes. In the end, captivity may have saved the chinchilla from extinction but did not end its exploitation.

PRIMARY SOURCES

- “Chinchillas: They Are Multiplying at Great Rate in the U.S.,” Life, April 1946.

- Drake, Waldo. “Shipping News.” Los Angeles Times. 22 August 1939.

- Haig, John Angus. “The Rodent That’s Worth More than Gold.” Nation’s Business, August 1937.

How to cite

Vergara, Ángela. “From Wilderness to Breeding Farms: The Domestication of the Chinchilla lanigera.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2022), no. 15. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9531.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Ángela Vergara

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Acosta, José de. Natural and Moral History of the Indies. Edited by Jane E. Mangan. Translated by Frances Lopez-Morillas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Albert, Federico. La Chinchilla. Santiago: Imprenta Cervantes, 1901.

- Gay, Claudio. Zoología. Vol. 1. Historia Física y Política de Chile. Santiago: Museo de Historia Natural de Santiago, 1848.

- Iriarte, J. Agustín, and Fabian M. Jaksić. “The Fur Trade in Chile: An Overview of Seventy-Five Years of Export Data (1910–1984).” Biological Conservation 38, no. 3 (1986): 243–53.

- Kellogg, Charles E. Chinchilla Raising. Leaflet 266. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, 1953. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112101920780.

- Soluri, John. “Something Fishy: Chile’s Blue Revolution, Commodity Diseases, and the Problem of Sustainability.” Special issue, Latin American Research Review 46, no. 4 (2011): 55–81. doi:10.1353/lar.2011.0042.

- Valladares Faúndez, Pablo, Carlos Zuleta, and Ángel Spotorno. “Chinchilla lanigera (Molina 1782) and C. chinchilla (Lichtenstein 1830): Review of Their Distribution and New Findings.” Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 37, no. 1 (2014): 89–93. doi:10.32800/abc.2014.37.0089.