The Triglav National Park, situated in the Julian Alps in Slovenia close to the border with Italy and Austria, is named after the country’s highest peak. Although the present-day park boundaries were established in 1981 under the socialist regime in Yugoslavia, the origins of nature protection in the Julian Alps date back to the Habsburg monarchy. Despite the changes of political systems and national boundaries, the highlands of the Julian Alps were always of particular interest to scientists and conservationists. The idea of a national park in the Julian Alps was appealing enough to survive imperial dissolution, border changes, and two world wars.

Triglav from the South. In the valley of Veljo Polje, Vodnikov Dom is visible, a mountain hut operated by the Slovenian Alpine Club.

Triglav from the South. In the valley of Veljo Polje, Vodnikov Dom is visible, a mountain hut operated by the Slovenian Alpine Club.

2012 Suzana Jerebič

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In 1907, professor of seismology Albin Belar was commissioned by the Habsburg administration to compile a list of natural monuments worth protecting. Among others, he proposed setting aside the Valley of the Seven Lakes below the Triglav, which he deemed of interest for science and, due to its low economic value, easy to protect. Nevertheless, concrete protective measures were not established until after the Yugoslav monarchy succeeded the Habsburg reign. In 1924, the conservationists of the Museum Society’s Department for Nature Protection in Ljubljana and the Slovenian Alpine Club signed a lease agreement with the Forest Directorate which set aside the Valley of the Seven Lakes with the understanding that all institutions involved would support the project of the “Alpine Protection Park.” However, enforcement of conservation measures was poor. Peasants insisted on their usage rights of the pastures, and tourists, too, were all too often inclined to walk off the beaten tracks.

“Forbidden” – a rather traditional sign in the Triglav National Park on Mangart Pass, the highest mountain pass in Slovenia.

“Forbidden” – a rather traditional sign in the Triglav National Park on Mangart Pass, the highest mountain pass in Slovenia.

2009 Carolin Roeder

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Over the course of the twentieth century, and increasingly after the Second World War when Slovenia was a republic in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, emerging narratives of Slovenian national identity drew on the symbolic power of the Alps. National identity thus secured political and public interest in the Triglav area, with the peak becoming Slovenia’s prime national symbol. Nonetheless, political inertia and competing interests between farmers, the park administration, local city governments, and the central government would impede conservation measures for decades to come.

In 1961, the Slovenian parliament established the Triglav National Park, yet it did not even come close to the standards set by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It covered only 2,000 hectares and remained relatively open for economic activities. When the national park was extended in 1981, the special law on the Triglav National Park distinguished between two zones of different protection levels (core and periphery) that corresponded to the IUCN categories II (National Park) and V (Protected Landscape).

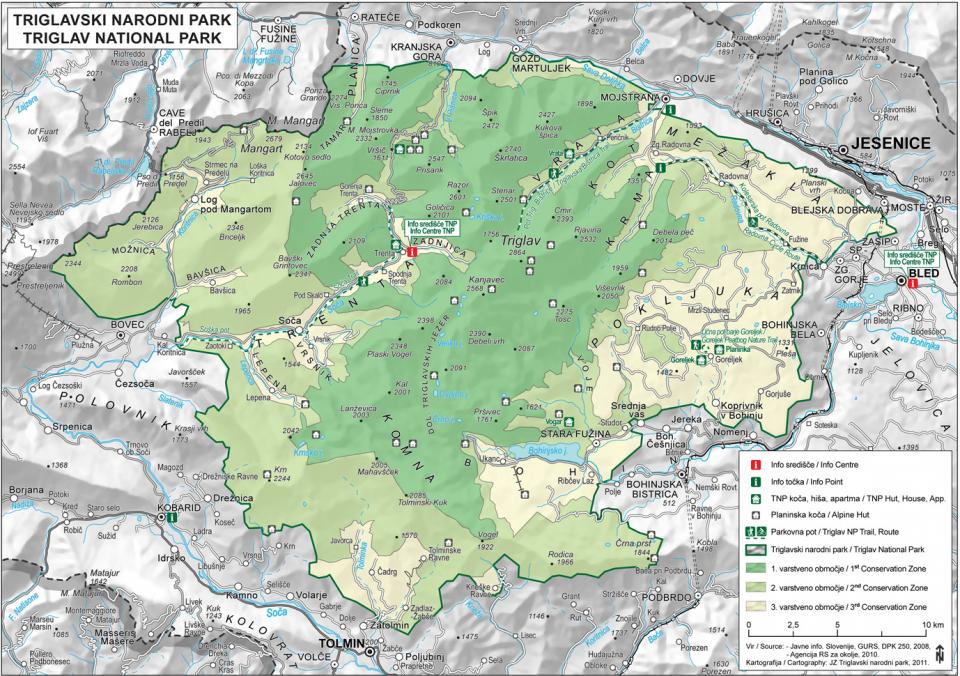

Map of Triglav National Park

Map of Triglav National Park

All rights reserved © Triglav National Park

Click here to view TNP source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Slovenia became independent in 1991; it was time to replace the out-dated regulations. Severe debates over the future use of the park had polarized politicians, the public, and non-governmental organizations. Discussions about restoring the previous ownership of parts of the park linked conservation to the question of the role and rights of the church (which owns large parts of the park’s territory) in the postsocialist society and denationalization in general. It took a decade of negotiation before a new law concerning the Triglav National Park was finally passed in 2010.

How to cite

Roeder, Carolin. “The Triglav National Park: A Century-Long Project.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2013), no. 13. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5452.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2013 Carolin Roeder

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Belar, Albin, “Die Naturdenkmalstelle in Österreich mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Landes Krain,” Wiener Zeitung, 9 June 1907, 3.

- Peterlin, Stane, “Nekaj o zametkih in začetkih varstva narave v Sloveniji,” Varstvo spomenikov 20 (1976).

- Roeder, Carolin Firouzeh. "Slovenia’s Triglav National Park: From Imperial Borderlands to National Ethnoscape." In Civilizing Nature: National Parks in Global Historical Perspective, edited by Bernhard Gissibl, Sabine Höhler, and Patrick Kupper, 240–55. New York: Berghahn Books, 2012.

- Šaver, Boštjan. Nazaj v planinski raj: alpska kultura slovenstva in mitologija Triglava. Ljubljana: Fakultet za družbene vede, 2005.

- Singleton, Fred, “Parks and Conservation of Nature in Yugoslavia.” In Environmental Problems in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, edited by Fred Singleton, 183–98. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1985.

- Skoberne, Peter, “Prispevek poznavanju vloge Albina Belarja na področju varstva narave na Slovenskem,” Annales, Series Historia Naturalis 21, no. 1 (2011): 97–110.