Between the end of 1922 and the beginning of 1923 the Italian government established two national parks, one in the Alpine Gran Paradiso range and the other in the Upper Sangro Valley, Abruzzo, central Italy. In this manner Italy became one of the first countries in Europe to create large nature reserves. This brilliant result was achieved through an intense effort developed by the Italian nature protection movement from 1911.

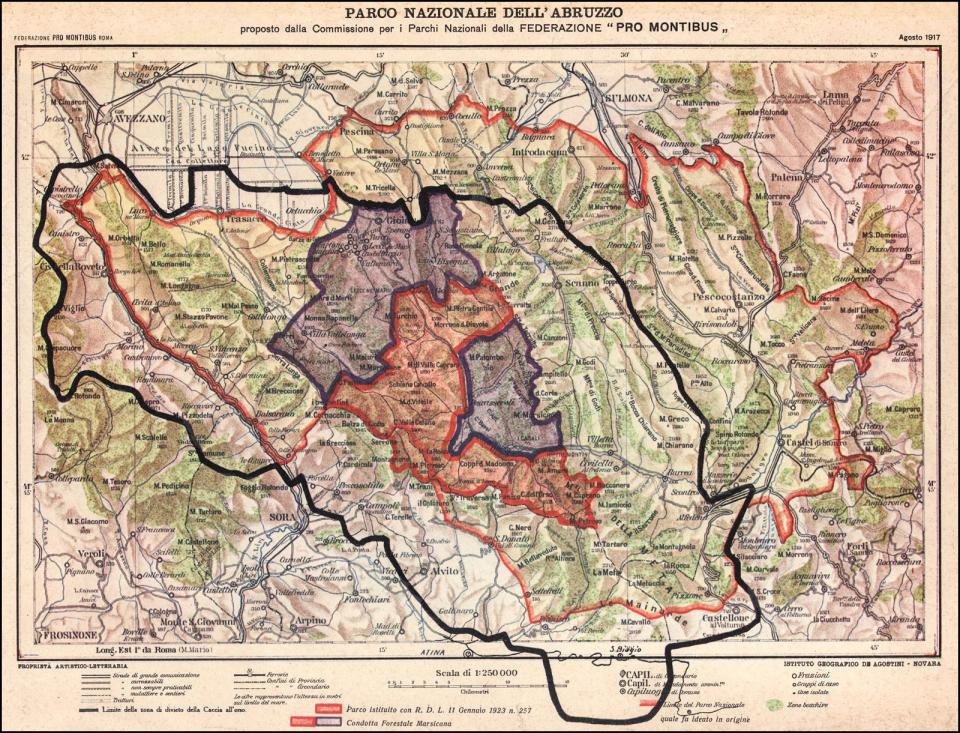

The original plan for Abruzzo National Park (external red line),1914, included about 50 human settlements. At the time of the park’s institution five villages were within the borders of the park (red area), totaling about 8,000 inhabitants.

The original plan for Abruzzo National Park (external red line),1914, included about 50 human settlements. At the time of the park’s institution five villages were within the borders of the park (red area), totaling about 8,000 inhabitants.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Ente Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo Lazio e Molise.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Gran Paradiso and Upper Sangro Valley were, however, very different areas. The entire planned Alpine reserve was located at high altitude; its supporters envisioned a national park like the one that had been created in Switzerland in 1914, which was mainly devoted to scientific research. Moreover, the Royal House and the King personally endorsed the proposal since the new institution meant they would not have to dismiss the gamekeepers of the royal hunting reserve; instead, the gamekeepers could become the national park’s new rangers.

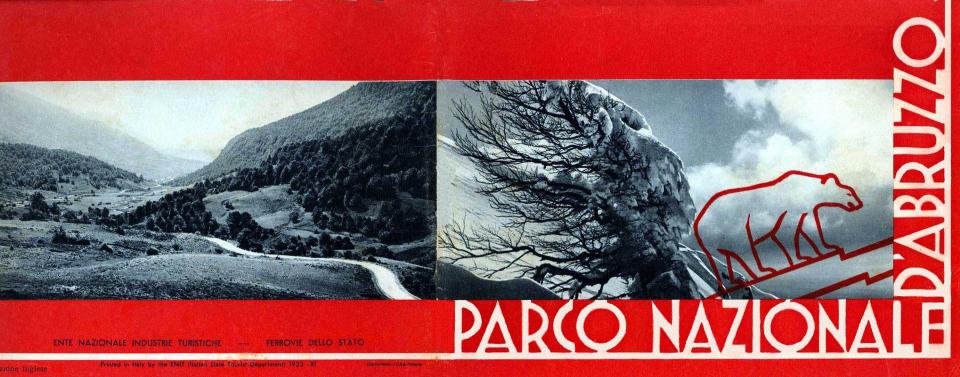

After the dismantling of the royal hunting reserve in 1912, the Marsican bear was threatened with extinction. This was the main reason for the proposal of a national park in the area.

After the dismantling of the royal hunting reserve in 1912, the Marsican bear was threatened with extinction. This was the main reason for the proposal of a national park in the area.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Ente Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo Lazio e Molise.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The park in Abruzzo, in contrast, was to be located in a densely populated area, making it potentially the first European national park to host thousands of people within its borders. Furthermore, the Royal House had dismantled its hunting reserve there in 1912, so it had few reasons to endorse the project. Between 1920 and 1921, therefore, the chances of establishing a national park in Abruzzo were much smaller than in the Gran Paradiso range.

In spite of these difficulties, the birth of the Abruzzo National Park was brought about by an alliance—unprecedented in Europe—among very different actors. This alliance included national scientific societies fighting for the protection of the Marsican brown bear (Ursus arctos marsicanus) and the imposing beech forests of the Upper Sangro valley, nature protection and tourism associations, ministry offices caring for natural beauties, several members of the Italian Parliament, and, most of all, the valley’s notable families together with the vast majority of local residents, all of whom were hoping for the touristic development of the area.

Notable residents of the Valley strongly supported the idea of a national park because they considered it a potential stimulus for tourism development.

Notable residents of the Valley strongly supported the idea of a national park because they considered it a potential stimulus for tourism development.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Ente Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo Lazio e Molise.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Some of these actors were also the driving forces of the Italian environmental movement at the beginning of the century. Very active indeed were the nature protection groups Società Botanica Italiana, the Unione Zoologica Italiana, and Pro Montibus et Sylvis—a national association aimed at the advancement of mountain communities—as well as the tourism-oriented organizations Touring Club Italiano and Club Alpino Italiano. Furthermore, since 1905 the Arts and Monuments Directorate of the Education Ministry had been at the forefront of the protection of monuments, landscape, and nature, mainly thanks to Luigi Parpagliolo, the most astute and cultivated spokesperson of the Italian movement. In 1913 all these subjects had joined forces in a federation promoted by the Touring Club that gave them further visibility and strength on the national scale.

Between 1919 and 1921 the government declared several times that it was extremely difficult—if not impossible—to create a national park in Abruzzo because of the dramatic situation of the state budget after four years of war. Therefore, in November 1921, the project’s promoters established a National Park Authority as a private initiative with the aim of forcing the Ministry and Parliament to formally acknowledge the existence of the protected area. The move received great support and proved very effective, so much so that fourteen months later the King signed decrees for the creation of both the Alpine and the Apennine reserves.

9 September 1922: Local member of Parliament Erminio Sipari inaugurates the Abruzzo National Park as a private reserve. Four months later it will be recognized by the state.

9 September 1922: Local member of Parliament Erminio Sipari inaugurates the Abruzzo National Park as a private reserve. Four months later it will be recognized by the state.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Ente Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo Lazio e Molise.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Indeed, the combination of dialogue, collaboration, and conflict among local actors, political representatives, national associations, ministry offices, and Parliament remained the crucial driving force of the Abruzzo National Park’s life over time, shaping one of the most dramatic and influential stories of Italian nature protection.

How to cite

Piccioni, Luigi. “Nature, Beauty, Tourism: The Concurrent Roots of Abruzzo National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2016), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7419.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2016 Luigi Piccioni

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Arnone Sipari, Lorenzo, ed. Scritti scelti di Erminio Sipari sul Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo (1922-1933). Trento: Temi, 2011.

- Kupper, Patrick. Creating Wilderness: A Transnational History of the Swiss National Park. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

- Piccioni, Luigi. Erminio Sipari: Origini sociali e opere dell’artefice del Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo. Camerino: Università di Camerino, 1997.

- Piccioni, Luigi. Il volto amato della Patria: Il primo movimento per la conservazione della natura in Italia, 1880–1934. Camerino: Università degli Studi di Camerino, 1999.

- Piccioni, Luigi. “La natura come posta in gioco: La dialettica tutela ambientale-sviluppo turistico nella storia della regione dei parchi.” In Storia d’Italia: Le regioni; Abruzzo, edited by Massimo Costantini and Costantino Felice, 921-1074. Turin: Einaudi, 2000.

- Piccioni, Luigi, ed. Ninety Years of the Abruzzo National Park 1922-2012. Proceedings of the Conference Held in Pescasseroli, 18-20 May 2012. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

- Sievert, James. The Origins of Nature Conservation in Italy. Bern: Peter Lang, 2000.